How Fred Astaire Influenced Jackie Chan

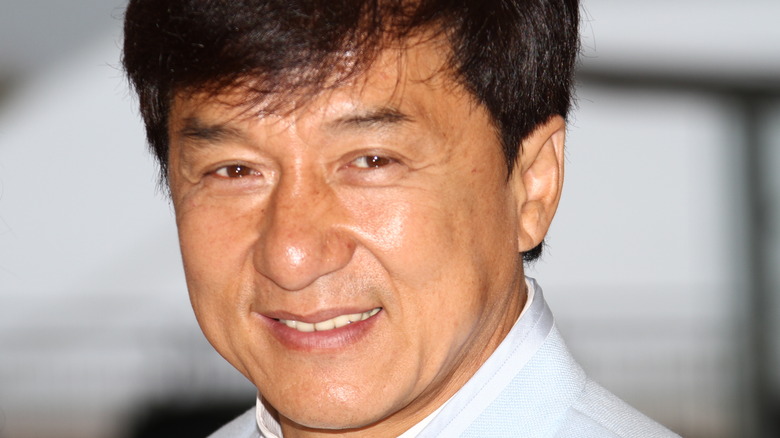

Jackie Chan may never have quite made it past B-list status in the U.S., but it's no exaggeration to call him the biggest global movie star of all time. Known for a long string of Hong Kong mega-hits, including "Drunken Master," "Mr. Nice Guy," and "Who am I?," along with American films like "Rush Hour," "Rumble in the Bronx," and "Shanghai Noon" (not to mention a hit Saturday morning cartoon), Chan's signature mix of martial arts and slapstick comedy has made him one of them most famous — and one of the best-paid — performers in the world.

One of the few "auteurs" working in action cinema, Chan is known for writing, directing, producing, and starring in all of his films. Trained in both kung fu and hapkido, Chan also does all his own fight scenes and stunts, famously turning every prop on the set into a weapon as he dispatches wave after wave of obligatory bad guy. As author Donald Westlake once colorfully put it (via Decent Films), "Jackie Chan is Fred Astaire, and the world is Ginger Rogers" — which, if Chan is to be believed, might be even more true that Westlake realized.

Jackie Chan vowed to become the anti–Bruce Lee

Chan had a deeply tragic upbringing and, in a 2000 interview, told The New York Post that his cash-strapped father almost sold him to the obstetrician who delivered him. Instead, he sent him to a "Dickensian" opera academy where students were forced to train for 19 hours a day not only in dancing and singing, but also in swordfighting, martial arts, and tumbling; students who failed to live up to expectations were routinely beaten, according to an interview in The New York Times Magazine

Unfortunately, the Chinese opera industry went into decline just as he was graduating, so Chan pursued a career in film, which didn't take off right away. In his early films (including "New Fist of Fury," a direct sequel to the Bruce Lee vehicle "Fist of Fury"), producers tried to cast him as the successor to then-recently deceased martial arts star Bruce Lee, who had been known for embodying the essence of the stoic kung fu movie badass. Sensing this wasn't working for his career, Chan vowed to become Lee's direct opposite (quoted in The New York Times Magazine): "I look at Bruce Lee film. When he kick high, I kick low. When he not smiling, always smiling. He can one-punch break the wall; after I break the wall, I hurt. I do the funny face." In other words, Chan set out to create a new kind of martial arts film.

Chan's surprising influences: Fred Astaire, Errol Flynn, Harold Lloyd

Chan knew he had to broaden his scope beyond just the typical Hong Kong fare, drawing from his vast knowledge of classic Hollywood cinema, later telling the The New York Post, "Everything I learned is from the countless movies I've seen." Some of Chan's influences were more obvious than others — swashbuckling star Errol Flynn clearly had some influence (via Mental Floss) — but some only become clear on closer inspection.

Chan's other influences include silent comedy auteurs Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, and Buster Keaton — all of whom, like Chan, are known for directing their own films and doing their own stunts. (This YouTube video shows some of Chan's scenes that directly quote Chaplin's, Keaton's and Lloyd's work.)

Perhaps some of Chan's more surprising influences, though, are Hollywood dancing legends Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly. Chan took two big lessons from the dance sequences in Astaire's and Kelly's films: long takes with few cuts — thus making sure the dance (or fight) showcased the star's physical ability, as opposed to mere camera trickery — and extensive use of props and scenery to give the dance or fight a clear sense of place.

"When he's dancing," Chan told The Los Angeles Times of Astaire, "it's not only dancing. He can move the light post and slide to the piano and dance with a chair. I try to use everything around me. When I'm not punch-kicking, I will fight with the refrigerator and the television and the radio."