The Tragic Story Of The Mount Erebus Disaster

Ah, Antarctica. Vast, unspoiled landscape. Ice, snow, and penguins. Oh, and also it's freezing. Yeah, unless you're a scientist or you have always dreamed of running with the penguins, Antarctica doesn't really have much to offer. Still, it's on a lot of bucket lists, on account of it being one of the seven continents, and therefore a must-see if your bucket list includes a stop on each of the world's great land masses.

Visiting Antarctica has always been sort of problematic, though. Not everyone is okay with freezing and there is also the problem of sailing across treacherous seas. But where there's a market, there's an entrepreneur, and by the 1970s there was a tidy little tourist trade happening in the skies of Antarctica. Until Air New Zealand flew a DC-10 and all its passengers into the side of a volcano.

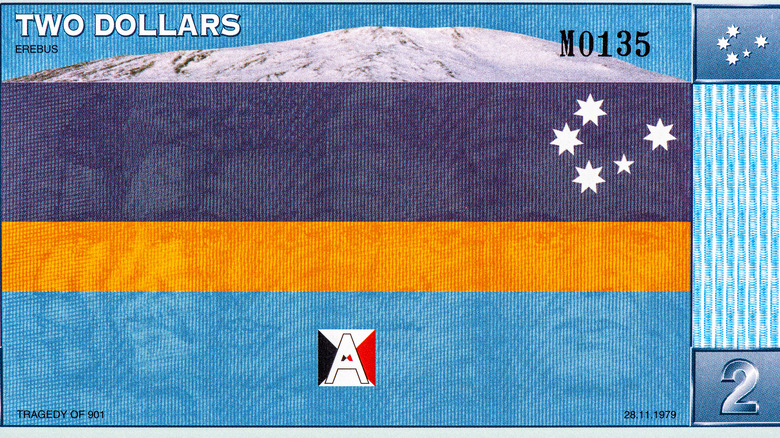

The Mount Erebus disaster was (and still is) New Zealand's worst peacetime disaster. The crash took the lives of 227 passengers and 30 crew members, and now more than 40 years later people still can't agree on exactly what happened or if it could have been avoided. Here's the tragic story of the Mount Erebus disaster.

The Mount Erebus crash was a huge blow to New Zealand's pride

New Zealand has Russell Crowe and Jemaine Clement, and also those weird birds that look like a cross between a tribble, a piece of autumn fruit, and a set of number 3 knitting needles. Less well-known is the fact that New Zealand has easy access to the southern continent. Antarctica is roughly 2,800 miles away at its shortest distance, which means it would take about as long to fly there as it takes to fly from Chicago to Anchorage, except you'd have to turn around without stopping. Still, it's close enough that if you're going to travel to the southern continent, it's probably a good place to start your journey.

In the 1970s this actually became sort of a point of pride for New Zealand. In fact according to the BBC, New Zealand was kind of the young nation equivalent of a teenager desperately trying to disassociate itself from its overbearing parents. At the time of the Mount Erebus disaster, the tiny nation had only been fully independent from the British Empire for roughly 30 years, and it was determined to prove to the world that it was a technological leader and a pioneer in exploration and nature-conquering and all that stuff that people used to think made nations great. And not unlike the incident with White Star Line and its famously "unsinkable" ship, Nature was annoyed by the boast.

Antarctica: Attracting tourists for 200 years

John Davis was the first person in the world to walk on Antarctic ice. That happened in 1821 — by the early 1900s explorers were falling all over each other on their way to the South Pole, because the planet was kind of running out of things you could be first at and everyone wanted to be the guy who got there before everyone else. By the end of 1911, the South Pole had been conquered, but the icy Antarctic landscape was still beckoning, only this time it was mostly regular people who wanted to be able to say they'd been somewhere most other people hadn't.

They had to wait for their chance, though. According to the Australian Antarctic Program, air travel to Antarctica didn't become a thing until 1928, and even then it was just one dude in a Lockheed Vega 1 monoplane. There were no passenger flights to the southern continent until 1964, when a LC130F Hercules made the grueling 15+ hour trip from Melbourne to Byrd Station.

Before that, the only way you could get to Antarctica was by boat, and it was flipping freezing so that alone was probably enough to dissuade a lot of would-be passengers. When airlines started selling seats on comfy frost-free airplanes in the 1970s, it's no wonder that airborne Antarctic tourism became such a successful business model.

The passengers were mostly affluent and middle-aged

You might imagine Antarctic explorers as super fit, rugged, young physical specimens with adventure coursing through their veins and a penchant for taking selfies with penguins, but that's not the sort of people who were on board Air New Zealand Flight TE901. This was strictly a sightseeing trip, which means you got to look down at the ice, not across it. It also meant that you paid a healthy sum for the experience, which does tend to rule out young physical specimens since young physical specimens often have a hard time scraping together beer money on a Friday night, never mind paying for a seat on an 3,000 mile journey to the bottom of the Earth.

In fact according to Erebus, most of the people who signed up for Air New Zealand's Antarctic adventures were "affluent," not necessarily wealthy but well-established professionals who did a lot of traveling and were otherwise out of ideas. They were also mostly middle-aged and older (though a batch of high schoolers who won a poster competition also made the trip two years before the disaster), so not the sort who would necessarily relish the idea of walking around parka-clad in sub-zero temperatures with a bunch of penguins. The flight gave them the best of both worlds — the opportunity to say they'd been to the farthest reaches of the planet without having to actually experience any of the discomfort associated with setting foot on the ice.

The ticket prices weren't even totally unreasonable

If you're going to visit Antarctica but also avoid frostbite, you might as well pull out all the stops. Air New Zealand made sure that their passengers flew in style — according to Erebus, everyone on board got first-class treatment, from a champagne breakfast to a lunch of bay prawns and scallops poached in white wine, and probably served on an actual plate instead of a weird microwavable plastic tray with a side of like seven honey roasted peanuts. All passengers were also given access to a full bar, you know, just in case they wanted to be too drunk to actually see Antarctica.

You're probably wondering how much something like this would cost — well, it was actually surprisingly affordable, even accounting for inflation. Tickets were $245 (in New Zealand dollars), which is equal to about $1,989 today, or $1,443 in American dollars. So at a little more than twice what you might pay for a round trip ticket from London to Los Angeles, prices were not totally out of reach for most mid- to upper-middle class people.

Compare that to what you might spend today — there are no longer any regular flights to the southern continent, so if you wanted a similar airborne adventure you'd have to charter a flight, and you'd pay around $6,000 for a one-day no-stops sightseeing flight roughly similar to the one taken by TE901 passengers, only (hopefully) without the tragic ending.

The pilot's experience wasn't enough to save the plane

Pilot Jim Collins was one of Air New Zealand's superstars — according to The New Zealand Herald, he was a career pilot who had a total of 20 years of experience with the airline.

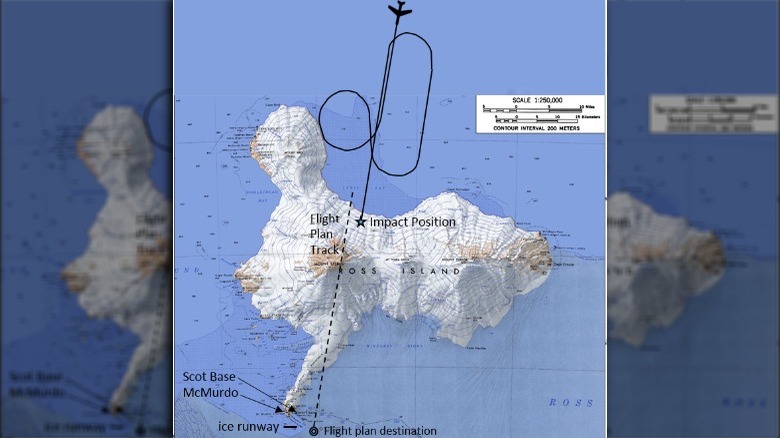

So what happened? Well, when your job is a pilot and you get told you're supposed to fly in yonder direction, you trust that the people telling you that know what they're talking about. But as it turns out, well, those people made a mistake. Collins and his co-pilot were given the wrong flight path — the route was in the same basic shape as the one they were supposed to use but it was actually over the wrong part of Antarctica. So instead of flying over McMurdo Sound, the flight path took them over Mount Erebus. And because this was a sightseeing tour, Collins decided to take the plane down to a lower altitude so passengers could have a better look — and unfortunately, the volcano's peak was higher than the plane.

Under any other circumstances, that wouldn't have been a huge problem because mountains in general are pretty big and easy to avoid, but the mountain wasn't the only thing that contributed to the crash. The official inquiry into the accident identified 10 factors, and concluded that if any one of those factors had been absent, the crash would not have happened.

Also they couldn't actually see anything

The thing that ultimately doomed the plane wasn't the flight path or the altitude or even the volcano. None of those things would have been a problem if Jim Collins had actually been able to see where he was going.

Collins was an experienced pilot, but most of that experience took place further north, and he was not familiar with a weather phenomena known as a "sector whiteout." Now, anyone who has lived in snowy places understands a whiteout as what happens in blizzard conditions when you can't see your own hand in front of your face, but a sector whiteout is a different sort of thing. According to Newsroom, during a sector whiteout the clouds kind of blend into the snowy landscape, so it looks like you're flying into a sheet of uninterrupted white. The New Zealand military knew about sector whiteouts, but sadly, Air New Zealand had declined to accept training from their much more well-funded military counterparts because reasons. At least, that's what the rumors say.

Still, the whiteout would have nothing but a footnote if the flight path had been correct, or if Collins hadn't taken the plane down to 2,000 feet. And it does explain why no one in the cockpit went, "Hey look, a mountain." By the time the proximity alarms went off, it was too late to avoid the volcano because it was 1979 and the not-flying-into-volcanoes technology wasn't especially well developed.

Back at home, no one knew what was going on

Aboard flight TE901, no one had any time to contemplate their fate. There was no warning, no time to send a distress call, no opportunity to let anyone back home know what was going on. To the people monitoring the flight, the plane had simply vanished.

After an hour of radio silence, a search and rescue operation was summoned. Meanwhile, Air New Zealand told the passengers' loved ones that there wasn't anything to worry about. The plane was due to arrive in Christchurch, New Zealand at 7:05 pm, but it wasn't until 9 pm that Air New Zealand said the plane was "overdue," which is a pretty roundabout way of saying that it probably wasn't ever coming back. Around 10 pm they finally admitted that Flight TE901 had most likely crashed.

According to New Zealand History, the wreckage was spotted by the crew of a U.S. Navy aircraft at roughly midnight, and the news reached New Zealand about an hour later. Based on the state of the wreckage, the crew of the Navy aircraft said there was little hope that anyone had been left alive. It wasn't until the next day that a trio of mountaineers who'd been brought to the wreckage by U.S. Navy helicopters confirmed that there were indeed no survivors.

Pretty much everyone in New Zealand was somehow connected to the Mount Erebus disaster

Plane crashes are violent, and the people who work on recovery efforts have an unenviable job. Two hundred and fifty-seven people died on board Flight TE901 — 227 passengers and 30 crew — and only 114 bodies were recovered. According to New Zealand History, the team also recovered passengers' personal belongings and "133 bags of human remains," which doesn't even bear thinking about, really.

Recovering the bodies is only the first part of the process. The hard part is identifying them — for that, a team of pathologists, photographers, police, fingerprint experts, embalmers, dentists, and funeral directors had to collaborate to figure out who the remains belonged to. In the end they were able to name 213 of the crash's victims, which doesn't sound great but is in fact pretty average compared to other plane crashes, because plane crashes don't tend to be kind to either their victims or to the people who love them. And recovery and identification were hard on the people who had to do it, too. The chief inspector of the operation later recalled that many of his younger staff suffered "quite bad psychological trauma."

Given how many people died on Flight TE901 and how many people were involved in the recovery, identification, and inquiry, the media was fond of saying there wasn't anyone in New Zealand — a small nation of only around three million people — who wasn't somehow connected to the disaster.

The recovery team found cameras in the wreckage, and then developed the film

You've probably occasionally snapped a photo of the wing of the 747 you're traveling on, but for the most part modern airline travel is dull, cramped, and not really something you want to memorialize forever and ever. Sightseeing flights, though, are a totally different story, because the reason you sign on to one is because you're actually interested in the piece of dirt, ice, or whatever it is that you're flying over.

One of the more heartbreaking details about the Mount Erebus disaster is that many of the "personal belongings" recovered from the wreckage were cameras, and in a lot of cases the cameras survived the crash even though their operators did not. Investigators retrieved and developed the film and today there is a photographic record of what happened in the final moments before the crash — though mercifully, not the crash itself because the passengers were all looking down, completely oblivious to the mountain that was looming in front of them.

According to Stuff, the photos were comforting to some of the family members, including the family of passenger Frank Christmas, who told Stuff that seeing film of Christmas on Flight TE901 helped give them closure 30 years after his death.

Whose fault was the Mount Erebus disaster?

For years, blame for the crash was lobbied at pilot Jim Collins, which made it really tough for his family to properly grieve. According to the New Zealand Herald, Collins' daughter, who was nine at the time of his death, recalls being told by a school friend, "Sorry about what's happened, but it was his fault." Because 9-year-olds are excellent at investigating disasters and drawing conclusions about blame. Anyway.

There was an awful lot of finger pointing happening just after the crash, and an awful lot of lying and diverting and generally infantile behavior. Air New Zealand did Not. Want. To. Accept. Blame. According to New Zealand History, the judge who presided over the public hearings accused Air New Zealand executives of a cover up and claimed that investigators had been fed "an orchestrated litany of lies." His report concluded that the fault belonged to the airline alone, and he ordered them to compensate the government and victims' families for their expenses. The Court of Appeal, though, ended up agreeing with the airline — it ruled that the judge had been out of bounds on a few issues, including the whole "litany of lies" thing and the fact that he hadn't allowed anyone from Air New Zealand to speak in their own defense.

People are still arguing about the Mount Erebus disaster today

Even today, there is still debate over who was at fault. In 1999, the New Zealand Minister of Transport was all, "can't we just pretend this never happened?" Well, not in exactly those words, but he did say it was time to stop playing the blame game, though evidently that only applied to the blame that had been levied against the airline. Ten years after that, Air New Zealand finally apologized to everyone who'd been impacted by the disaster. It was kind of 30 years overdue, but hey, better really, really, really late than never, right?

According to Newsroom, the families kind of languished in silent grief for the first 40 years following the crash, and it wasn't until 2018 that they were finally invited to Parliament to talk about building a memorial to the victims of flight TE901. By 2019, though, plans to build the memorial at the Parnell Rose Gardens in Auckland, New Zealand had been stalled by local people who thought it would make their park look ugly. The proposed site was later shifted to a more obscure open space in Auckland called Mataharehare, and as of the spring of 2021 families were still wrangling over whether or not they thought the location was suitable.

The wreckage of the plane is still on the slopes of Mount Erebus

The victims of the crash and their personal belongings were removed from the slopes of Mount Erebus in the weeks following the crash, but the wreckage itself is still there. It is usually covered with snow and ice, but according to the New Zealand Herald it does periodically reappear during warm spells. In 2005, mourners approaching the site for a 25th anniversary memorial service spotted the plane's tail and one of its engines on the slope of the volcano. It was the first time the wreckage had been seen in years.

Bickering has slowed the progress of a New Zealand memorial, but in Antarctica there is a modest memorial to the victims standing over Scott Base within view of Mount Erebus. Recovery workers placed the original wooden cross on a rock outcropping — it was replaced by a stainless steel cross in 1987 after wind and weather started to take a toll.