The Strange Reign Of Richard The Lionheart

Richard I "the Lionheart" was one of England's most famous and polarizing rulers. His Victorian-era statue outside Parliament reminds the English people of his service to God in the Third Crusade. But what would Richard have thought? His attitude toward England is captured in a saying, cited by Edith Thompson, "I would sell London if I could find a buyer."

Richard disliked England and spent less than a year there, so he can hardly be called "English" in the modern sense of the word. Instead, the king preferred his French domains, relegating England to a tax base for raising revenue to fund his wars. Richard's rocky relationship with England, his love of war, and his strained family relationships made for a strange yet fascinating reign that brought him from southern France all the way to the Holy Land, through Central Europe, France, and eventually, to heaven's gate.

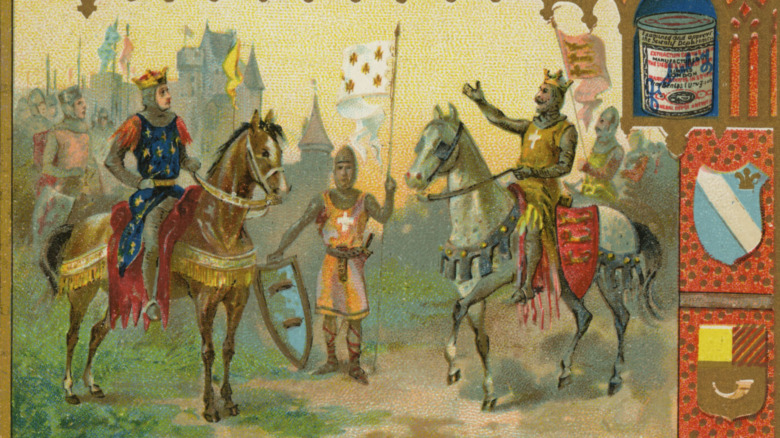

Richard's accession was the result of a family tragedy

Richard the Lionheart had to struggle to gain his power, pushing aside obstacles that included his own flesh and blood. William of Newburgh records that Richard's accession to the throne was anything but clean. Richard was second in line to the throne after his brother Henry III (who reigned alongside their father, Henry II). However, Henry III had died in 1183 following an attempt to oust Richard from Aquitaine that their father (Henry II) mediated. By law, the succession should have gone to Richard, but King Henry II wanted instead to leave the crown to his youngest son, John.

According to John Gillingham, Henry II tried to settle the sibling rivalries by limiting Richard's power through redistribution of his Aquitanian lands to his brothers (the very thing he had tried to prevent earlier). Unfortunately for Henry, it failed. William of Newburgh recounts that when Philip of France invaded English territory, Richard opportunistically joined him. Henry turned to the papacy to save his throne, but he was an old man and not in a position to resist his energetic son.

Henry hoped to obtain papal intervention and have Richard disinherited. But as the combined Aquitanian-French forces marched against him, John deserted his dying father and joined his brother. This act broke the old king's heart, and he died of disease in 1189, notes Historic UK, leaving England to Richard.

His mother was the power behind the throne

Behind every powerful man is a powerful woman. This cliché was certainly true in Richard's case, as he owed his position in part to the political maneuvering of his mother, Eleanor d'Aquitaine. Richard was heir to her lands in southern France, giving him a power base when he took over as duke, as well as noble supporters that would back him against his father. Eleanor, however, maintained a constant presence throughout his life.

Per the BBC, Eleanor hated her husband King Henry I for his mistresses and his attempts to interfere with her lands. Richard and his brother's rebellion in 1173 presented a chance for revenge on her husband. William of Newburgh writes that Eleanor rallied Aquitaine around Richard, who joined the rebellion. Unfortunately for Eleanor, Henry captured and imprisoned her for 16 years to guarantee Richard's loyalty. To ensure that his mother's safety, Richard stayed peaceful until 1189, when his father was nearly dying.

Among Richard's first acts as king was to send for his mother's release. His subjects, though, knew of his affection for her and had already let her go. According to historian Alison Weir, Eleanor styled herself as queen of England during her son's rule, and Richard addressed her as "Queen of England, his much-loved mother." Since Richard did not marry until 1191 and did not care about his wife anyway, this does not appear to have been a problem. It would pay off for him later when his mother acted as his regent and saved him from an Austrian prison.

Some claim the French king was his lover

Despite his warlike achievements and prestige, Richard persistently refused to marry and never sired any known children. When he finally married Berengaria of Navarre in 1191, she became the English queen who never set foot in England, per Columbia University project Epistolae. This suggests that Richard rarely saw her or had relations with her. The king's strange private life led to insinuations that he was a homosexual, as summarized in the Guardian.

According to Roger of Hoveden, Richard spent some time with King Philip of France, dining and spending many days with him and that "beds did not separate them." While there are other interpretations of this passage that suggest platonic friendship, another citation from Hoveden mentions a priest warning Richard to avoid the sins that resulted in the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, of which homosexuality was one. The passage says that Richard repented of "illicit intercourse," which can be interpreted either as adultery with other women or homosexuality.

The question of Richard's sexuality is still open, and it will never be known for certain. Current evidence, however, suggests he was not a homosexual, and that the sins in question referred to something else. John Gillingham has noted that such language occurs in other texts that show either purely platonic relationships or close political ties and personal ties between rulers. Nevertheless, Richard's adamant rejection of marriage is strange and a tad suspicious, but perhaps he just loved the din of battle too much to waste his time on women.

Richard the Lionheart spoke English very poorly, if at all

Today, it would be expected of an English monarch to have at least some, if not full, command of the English language. Most modern English monarchs have fit this requirement. In the Middle Ages, though, this was not the case. In Richard's time, European states had several common languages and an official prestige language. According to the University of Norwich, Richard the Lionheart ruled England at a time when the country's official languages were French and Latin. Latin was the ecclesiastical language and that of official records. French was the language of the court, brought over in 1066 by Norman conquerors. English was the language of the commoners, and generally, was not used in polite company.

The king's linguistic proficiencies reflected this divide in English society. Richard spent most of his life in Aquitaine (in modern southwestern France), which he inherited through his mother Eleanor. According to Historic UK, he probably did not speak English. Instead, as would be expected at the time, he spoke French, and more interestingly, the little-known Romance language called Occitan. This minority language, a close relative of Barcelona's Catalan language, was at the time the main language of southern France, prestigious for its repertoire of lyric poetry. It was also Richard's preferred tongue, which he used to compose poetry and conduct everyday business.

He loved Occitan lyric poetry and was a patron of the arts

In keeping with his affinities for the Occitan language, Richard was an avid patron of troubadours. According to the Harvard University English Department, these traveling bards sang of knights and heroes at the courts of their wealthy patrons. However, these poets were not only traveling bards. Sometimes, nobles attempted their hand at poetry as well, including Richard himself.

For Richard, poetry was a family tradition. His great-grandfather William IX of Aquitaine was among the first Occitan troubadours, while his mother was a patroness of many. Richard is known for the Occitan lament, "Ja nus hons pris" ("No imprisoned man"), which has been preserved with its music and can be enjoyed in numerous recordings.

Richard's love of music inspired a beautiful 13th century apocryphal legend that unfortunately is not true. In this tale, the duke of Austria had imprisoned Richard. Composer Edmundstoune Duncan recounts that a troubadour named Jean Blondel de Nesle roamed through Europe's castles singing a song that he and Richard had written together in a quest to find him. When he finally heard a singing voice responding to his, he found Richard's place of imprisonment. While the tale is just a tale, it illustrates that despite Richard's less likable qualities, his love of music and the arts made him stand out positively among monarchs of his day.

On crusade, he allegedly committed cannibalism as psychological warfare

Richard's best known exploits are from his time in the Holy Land. According to tradition, though, not all were positive. Upon his arrival in the Holy Land, he found the crusader army exhausted from the long, ongoing siege of Acre (now in Israel). To break the defenders' morale, Richard allegedly engaged in cannibalism. According to the 14th century romance "Richard Coer de Lyon," Richard was feeling ill and requested some pork. Because of the poor condition of the crusader siege camp, none could be found, so Richard ate some meat off a dead Muslim soldier instead. The English king made a spectacle of this, declaring that as long as there were dead Saracens, the crusaders would never want for provisions. Word of his terrible deed then reached Acre, filling the defenders with dread regarding the fate that awaited them if Richard were to be successful in storming the city.

This story is apocryphal and likely invented, as it has no precedent in any earlier sources relating to Richard. Per Conor Kostick, cannibalism by starving troops and civilians probably did occur in times of severe privation and famine, especially during the First Crusade in 1098. In Richard's case, however, it seems the stuff of fancy.

He never lost a battle but lost the war

During the Third Crusade, Richard's martial prowess and tactical skills proved invaluable to the crusade's successes. Per the "Itinerarium Peregrinorum et Gesta Regis Ricardi," the city of Acre fell in 1191 thanks to his leadership and forced the Egyptian Sultan Saladin onto the defensive. Richard then won his greatest victory against Saladin at Arsuf. Despite being outflanked and outmaneuvered, the English king turned a disorderly and unexpected cavalry charge into a surprise attack that routed the overconfident Muslim forces. He then defeated Saladin a third time at Jaffa, clearing the road to Jerusalem.

According to "English Monarchs," when Richard reached Jerusalem, he received news that his brother John was attempting to usurp the English throne, depriving Richard of his main title and source of revenue. The English king decided to end the crusade with the 1192 Treaty of Jaffa so he could return to England. The truce allowed Christian pilgrims to visit Jerusalem, a small victory for Richard. However, the city remained in Muslim hands, and if the crusade's goal was to retake Jerusalem, then Richard, despite not losing a single battle, lost the war.

Richard was a generous and founding trustee of the Vienna Mint

The City of Worms records that once Richard discovered John's plot, he hastened back to England through central Europe, eventually reaching the hostile Duchy of Austria. During the siege of the city of Acre, Richard had insulted Austrian duke Leopold I, tearing his banner off the city walls and throwing it to the ground. Leopold now got his revenge, imprisoning Richard and turning him over to Holy Roman Emperor Heinrich VI, who held him in Worms.

According to Angevin World, Heinrich demanded the exorbitant ransom of 150,000 marks (100,000 pounds of silver) for his freedom, even though Richard was entitled to safe passage under the crusader cross. Richard's captivity launched a bidding war. He could not pay 150,000 marks, almost three times England's annual income. Furthermore, his rivals, Philip of France and his brother John upped the ante, offering Heinrich 80,000 marks each to keep Richard in captivity.

Just when Richard's situation seemed hopeless, his mother Eleanor saved him. She raised the necessary funds through exorbitant tax increases on the English population, sales of land and titles, and the seizure of valuables from clergy and nobility alike, as described in Roger of Hoveden's chronicle. Today, there are almost no valuable objects made of silver in England that date to Richard's reign because of this ransom. Per the Vienna Mint, Leopold invested his part of the ransom to create the now-world famous institution. Today, the Vienna Mint honors Richard's captor Leopold with an 825th anniversary 1 ounce silver coin. However, Richard was not forgotten, as he was honored in 2009 with his own silver coin, preserving his legacy as the mint's first "trustee."

The crusade earned him the ire of the church

One would think that the Catholic Church in England would have loved Richard for his successes in the crusades, which gave the Christian states in the Holy Land a chance of survival and nearly returned Jerusalem to Christendom. Yet, despite all of the suffering Richard endured during the crusade on the church's behalf, the church disliked Richard for making them pay for it.

The clergy in medieval Europe was on paper exempt from royal taxes. In Richard's time, however, the English church came under heavy taxation. To fund the Third Crusade, Henry II imposed the "Saladin Tithe" on England's monasteries and abbeys, demanding taxes in supplies from institutions that were accustomed to not paying them. With Henry's death in 1188, it fell to Richard to collect the remaining balance, earning him the clergy's dislike, even though the money was for holy war.

William of Newburgh complained of Richard's avarice in contrast to his father Henry II, whom William called a true patron of the church (a highly questionable characterization). He decried Richard's taxation of the monasteries, while the Welsh chronicler Gerald of Wales (via historian Ralph Turner) compared Richard to a thief on the prowl, always looking for something to steal. Because of his fiscal treatment of the church, Richard's martial prowess on crusade was overlooked. Instead, Richard found admiration from some unexpected quarters.

His Muslim opponents, on the other hand, respected him

Ironically, Richard's skill and valor on the battlefield drew effusive praise from his Muslim enemies. Saladin's friend and biographer, the Islamic jurist Bahaeddin, lionized the English king as powerful, brave, and resolute in the very first mention of the king. Richard's arrival in the Holy Land sowed terror among Saladin's men and earned him respect not accorded to other crusader kings. As a testament to the dread he inspired, when Richard charged Saladin's army at Arsuf, not a single Muslim soldier dared engage him. Bahaeddin's praise for Richard came despite his massacre of Muslim prisoners at Acre, which the Muslim chronicler offered justification for.

Saladin's praise was more measured. According to historian Jonathan Philips, the Egyptian sultan noted Richard's recklessness and willingness to hurl himself into the fray, a backhanded compliment of his fearlessness. In 1192, a bishop visited Saladin and told him that an ideal prince would have the best qualities of the Egyptian sultan and the English king. Saladin is said to have agreed.

Richard, according to Saladin's contemporary Ibn al-Athir (in Philips), tested the Muslim armies and brought them to the brink of defeat. By his account, it was only through divine intervention that Saladin survived this onslaught. To receive such a compliment from his Muslim enemies was the highest praise Richard could have hoped for.

Richard's death was unworthy of a warrior king

After his ransom in 1194, Richard spent the rest of his reign fighting King Philip of France and rebellious vassals. In 1198, he faced a rebellion of his vassal Viscount Aimar de Limoges. Richard sacked and burned his way through his enemy's territories, eventually coming to the small castle of Châlus-Chabrol.

This castle was so small and poorly defended that it is unclear why Richard bothered to besiege it. Roger of Hoveden claimed that Aimar had discovered a hoard of gold, which Richard desired in its entirety, although John Gillingham has dismissed this as a rationalization of Richard's actions. If the story is true, then Richard's greed was his undoing. While the king was inspecting the siege lines, a local boy named Bertram shot him through the shoulder with a crossbow.

Eventually, Richard developed gangrene, notes History Extra. Once his death was inevitable, he pardoned his assailant after his forces captured the castle. Unfortunately, one of Richard's warriors killed the boy and all of the castle's defenders, per the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica. In an ironic twist of fate, Europe's greatest warrior, whom his enemies had not dared cross, had fallen to a peasant boy.

Richard's story did not end with his death

Richard's host of alleged sins, which included being a thief, a homosexual, and a tyrant were not markers of a pious man. English chronicler Ralph de Coggeshall (cited by historian Jean Flori) referred to him as a member of an "immense cohort of sinners." Yet his service in the crusade and the zeal with which he prosecuted the war suggests that he did have a certain level of piety and fear of God, as was expected of a medieval ruler.

Because of his reputation as "the Lionheart," Richard's heart was embalmed with aromatics such as myrtle, frankincense, and daisy (via Nature). The process created an odor of sanctity, like Christ's burial after the crucifixion. It was hoped that this odor would shorten his stay in purgatory. It is not known what Richard's time in purgatory would have been, but regardless of the treatment, he eventually entered heaven. In 1232, two English bishops (via John Gillingham) saw the king ascending into heaven in a vision after 33 years in purgatory to expiate his sins. For many of his admirers, it must have seemed a fitting end for the king who had served the cross so valiantly.