The Real Reason West Virginia Broke Away From Virginia

There are many mysteries connected to our great country. For example, why do we elect our presidents using the world's most confusing and unnecessarily complex system? Why do we have so many time zones? Who thought the roundabout was a good way to organize car traffic? And what, exactly, is the difference between a hoagie, a hero, a sub, and a grinder?

Most of these mysteries have pretty simple explanations, but one question requires a bit of a deep dive: Why do we have a West Virginia when regular Virginia seems like a perfectly acceptable state? Considering that West Virginia came into being a century-and-a-half ago, and its creation was obscured by some pretty huge historical events, it's easy to see why many folks don't really know why we bothered to carve out a whole new state nearly a century after Virginia's acceptance into the Union.

Saying that we have a West Virginia because of the Civil War is an easy hot take, but like most hot takes it's actually mostly wrong. The story behind the creation of our 35th state is a lot more complex than you might think. Here's the real reason West Virginia broke away from Virginia.

The root causes of the split pre-date America

Virginia was first formally colonized by the English in the early 17th century (typically, no one asked the Indigenous Americans already living there what they thought about this). But as The Washington Post explains, while the eastern part of the state was dominated by English tobacco farmers (and the slave culture they created and perpetuated), the western part of the colony was settled by German and Scotch-Irish settlers.

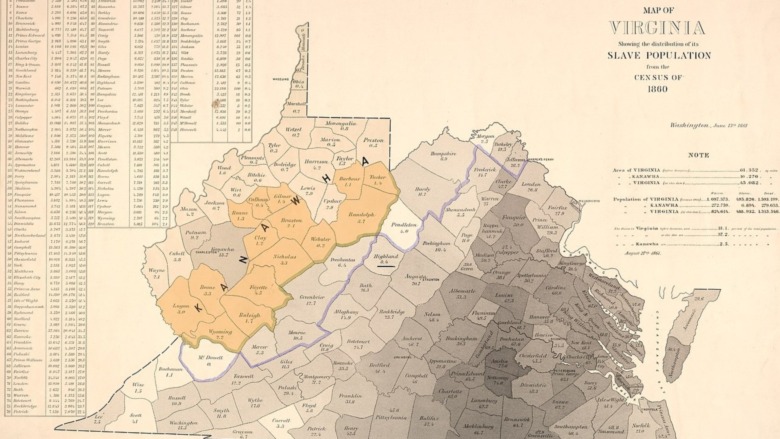

Aside from cultural and ethnic divisions, another reason the western part of the colony developed quite differently is down to geography. The western counties are isolated from the east by the Allegheny Mountains, which formed a perfect barrier that slowed down travel and communication, allowing western Virginia to develop very differently from the east. This affected everything from culture to the economy, as West Virginia was a more mountainous and rugged area that wasn't conducive to the slave-powered plantation economy of the east.

Even after the American Revolution and statehood, Virginia continued to be a state with two identities. As noted by Discover Richmond, these differences were enshrined in the state's 1776 constitution, which tilted power towards the east explicitly in terms of voting power, taxes, and public spending. The west's breakaway during the Civil War was the climax of more than a century of cultural, political, and economic division in the area.

The rivers played a big part

We tend to think of events like secession in political or economic terms—and those certainly played a huge part in West Virginia's decision to break away from Virginia. But underlying those broad issues are the geographical features that caused them in the first place. One example is the Allegheny Mountain range, which formed a formidable barrier that allowed the western portion of the state to develop independently. Another is the river system.

As explained by Virginia Places, the way the rivers flowed in Virginia impacted the state's history from the very beginning. After settling Jamestown in the early 17th century, the English didn't move westward—they moved north and south, because 80% of the rivers in the western part of the state flow into the Mississippi River, not the Chesapeake Bay, the port the tobacco farmers used to export their crops.

This also meant that the wealthy eastern part of the state, where all the political power was concentrated, didn't spend much in terms of infrastructure in the west. Improvements west of the Alleghenies simply wouldn't benefit them in the east, so there was continuous resistance to it, which led to deepening resentment in the west.

Most West Virginians weren't Virginians

America is a country of immigrants. Even from its very beginnings the population of what would eventually become the United States of America wasn't homogeneous, and the colony of Virginia was no exception.

As noted by Virginia Places, the area known as Tidewater Virginia, where the original colonial settlements began, was almost exclusively English. Descendants of those English colonists established the great plantations and created the slave economy of Virginia, and dominated the politics and economy. In fact, just 5% of the English-descended families in the colony—known as the First Families or "cavaliers" if you wanted to be fancy—controlled everything.

But as "West Virginia: A History" notes, the high-quality land in West Virginia encouraged enthusiastic land speculation, and most of the families that moved into the area didn't come from the east, and weren't Anglican English. Instead, they came from the north (mainly Pennsylvania) and they were largely Protestants—Pennsylvania Dutch as well as Scotch-Irish and Welsh. And because the land in West Virginia is very different from the Tidewater area, the western economy had little to do with the eastern portion of Virginia. Instead, West Virginians largely traded with areas north of them, primarily Baltimore and Philadelphia. As a result, western and eastern Virginia developed independently—and very differently—setting up a deepening rift.

Religion came into it

Religion has been intertwined with American history from its very beginnings—the Pilgrims on the Mayflower were fleeing religious repression in England and seeking the freedom to worship as they saw fit. So it's not terribly surprising that the split between East and West Virginia had a complex religious aspect to it as well.

As explained by Virginia Places, the eastern part of Virginia was originally settled by English immigrants who were primarily members of the Church of England (known as Anglicans). The Anglicans came to dominate every aspect of Virginia, from its politics to its economy. In fact, "West Virginia: A History" notes that the Church of England was literally the official religion of Virginia until 1786, when the state officially adopted the concept of separation of church and state.

In the western part of the colony, however, cheap land prices drew immigrants from a different religious background—Protestants. Many of these families had traveled to Pennsylvania in order to escape the religious intolerance back in England. In other words, they'd fled England to escape Anglicans, then moved into a colony (and later a state) controlled almost exclusively by English Anglicans. That proved to be a good way to set up a future split.

West Virginians tried once before

From its earliest days, West Virginia was different from the eastern part of the colony. In terms of religion, economics, and politics it was a distinct region, isolated by geography. The people of West Virginia were very aware of this, and long before the Civil War brought these differences to a final head they were ready to break away—in fact, they tried to form their own colony in 1775.

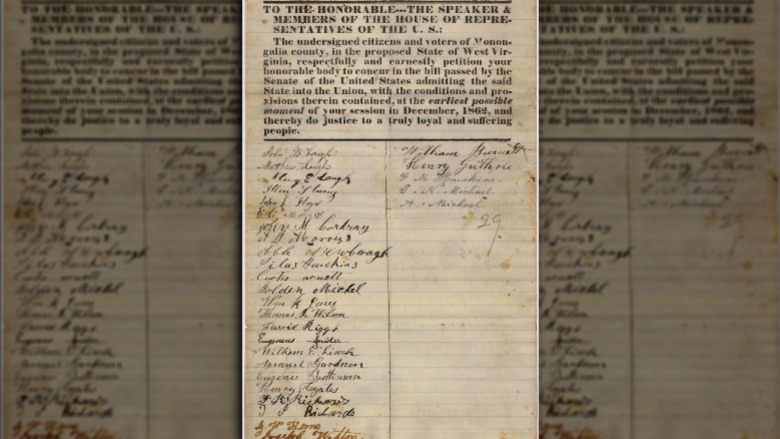

According to the Observer-Reporter, the idea dates back to at least 1763. In the wake of the French and Indian War, a group of influential Americans floated the idea of a separate colony formed out of lands ceded by Indian tribes on the losing side of the conflict. The idea didn't take off, but as History tells us after the Continental Congress was formed, residents in West Virginia tried again, sending a petition in 1775 asking that a 14th colony called Westsylvania be formed. The 2,000 petitioners certainly thought big: Their proposed borders included not just what is modern day West Virginia but also portions of Maryland, Virginia, Kentucky, and Pennsylvania.

The Encyclopedia Britannica notes that these efforts were a direct result of the growing differences between the eastern and western populations of Virginia, and the West's lack of political power made forming their own colony an attractive idea. The Continental Congress ignored the petition, and in 1783 ignored a second petition asking that Westsylvania be made the 14th state.

A power imbalance was hard-coded

Representative government only works when power is equitably divided. When one group puts their thumb on the scale to deny another their fair share of power, it inevitably leads to friction. Which is exactly what happened in Virginia between 1776 and 1863.

Discover Richmond explains that the state constitution of Virginia adopted in 1776 was engineered to favor the wealthy eastern power brokers in the state. It specifically tied voting to property ownership. Since the wealthy eastern elites were the largest property owners in the state and many of the people living in the west were tenants, this meant the eastern portion of the state had a hard-coded political advantage that allowed them to not only shape laws in their own favor but to ignore the needs of western citizens without fear of political reprisals.

The implications of these imbalances went beyond simple political power. As "Old Dominion, New Commonwealth: A History of Virginia, 1607–2007" explains, the constitution ensured that the bulk of the western population weren't considered to be equals, violating one of the key tenets of the American Revolution. This set the stage for West Virginians to become increasingly dissatisfied by their status and lack of political clout.

The taxes were unfair

One common thread throughout American history is our reluctance to pay taxes—and a strong determination that if we do have to pay taxes we should do so fairly. Concern over unfair taxation spurred the revolution that formed this country, after all, and our current political conversation is still very focused on the issue. So it's not really a surprise that one reason West Virginia split away from Virginia was the tax code.

As noted by Discover Richmond, the tax code in Virginia prior to the Civil War benefited the eastern elites much more than their less affluent western counterparts. The code was designed to favor people who owned huge plantations and many slaves, which was only possible in the eastern Tidewater region of the state. Not only did this mean westerners paid an unfair amount of tax, it also meant the eastern elites who controlled the government saw no reason to spend money in the west. History explains that slaves were counted when representation in the state government was determined, giving the slave-owning easterners a baked-in advantage and insulating them from western anger. As a result, the western portion of the state languished in terms of infrastructure investments. This lack of response from their own government stoked the feeling in western Virginia that they had to stage their own mini-American Revolution in order to escape what was essentially taxation without representation.

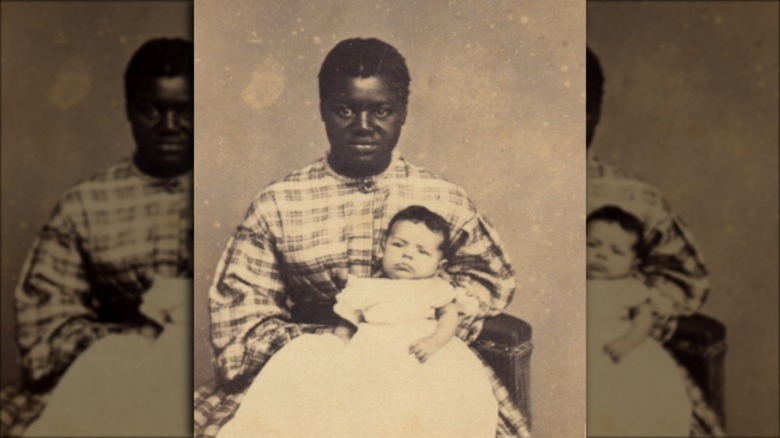

Slavery was a big part of reason West Virginia broke away from Virginia

There were many divisions pulling West Virginia away from Virginia, but one of the biggest and most important centered on slavery. As The Culture Trip points out, there was a much greater abolitionist sentiments in the western portion of the state than in the east, in part because, as History reports, there was a near "absence" of slavery in the region. This wasn't so much a moral issue as a practical one, however—the eastern plantation owners were heavily invested in slave culture and a slave economy, whereas the western part of the state was less conducive to the economics of slavery. The simple fact was that there were fewer slave owners in the west, but as The Washington Post notes the slave-dependent easterners had all the political power.

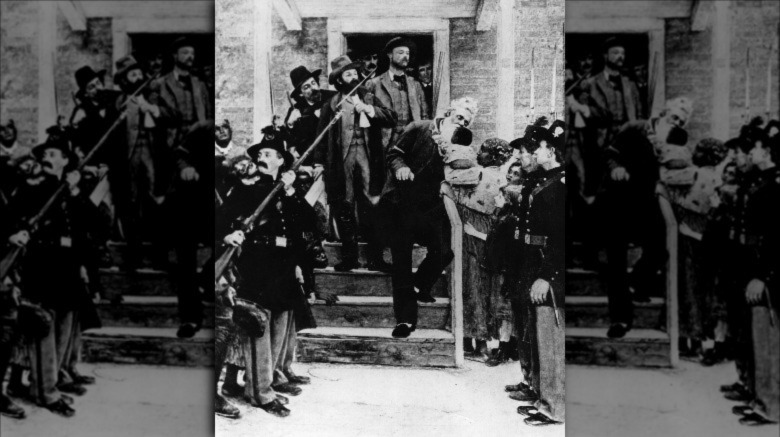

When the abolitionist John Brown staged his raid on Harpers Ferry—today part of West Virginia—his main reasons for choosing that location were practical—Harpers Ferry was a federal arsenal filled with the weapons Brown thought rebellious slaves would need to fight for their freedom, and the location offered easy access to the South. But another reason was what Discover Richmond describes as "the emergence of western anti-slavery ideology." While this position against slavery wasn't necessarily a moral one, it suggested a friendly reception to the abolitionist movement. When the whole country split apart largely along slavery lines, it was natural for West Virginia to side with the Union—and break away.

West Virginia wasn't so much anti-slavery as anti-slaveowner

While slavery was a huge issue contributing to West Virginia's push for independence from Virginia, it wasn't necessarily an abolitionist, moral stance—in fact, West Virginia wasn't so much anti-slavery as it was anti-slaveowner. As History points out, this was more about politics than morality: The wealthy slaveowners of eastern Virginia owned lots of slaves—and those slaves counted towards deciding how many representatives a county could send to the state government. The result was political dominance by the eastern elites, making the western counties seethe.

This resulted in a slow boil of resentment, as the east-dominated state government ensured that everything from taxes to infrastructure investments heavily favored the eastern portion of the state. Because their lack of slaves and property kept them trapped in a powerless cycle, western Virginians couldn't do much about it—until the outbreak of the Civil War offered them an opportunity to finally formally break away.

This attitude becomes evident when you note how weak West Virginia's anti-slavery stance was once it became a state. As noted by HistoryNet, its constitution originally only freed slaves gradually—and many would have remained slaves their entire lives. It wasn't until 1865, two years after statehood and just before the passage of the 13th amendment abolishing slavery, that West Virginia officially ended legal slavery.

Virginia tried to fix its relationship with the west

The wealthy landowners that dominated Virginia prior to the Civil War were very much aware of the fact that the Virginians living in the west of the state were unhappy. While they weren't much inclined to do anything about it, enough political pressure was brought to bear on several occasions to force them to at least try.

According to "Old Dominion, New Commonwealth: A History of Virginia, 1607–2007," the first time these efforts achieved any results was in 1816, when western agitation convinced the legislature to establish some canal projects and banks in the west—but no substantive political change came of it. As noted by Discover Richmond, this exercise was repeated again in 1825 as reformers pushed for a revised constitution and received minor concessions instead.

Virginia Places notes that in 1830 things looked better for the West Virginians—the census had proved the population was booming in the west, and this pressured the eastern leaders to call for a constitutional convention. While the new constitution made significant changes to how power was distributed in the state, the balance of power was still tilted in favor of the old eastern families—and most of the West voted against it as a result. It wasn't until a second constitutional convention in 1850 that real concessions were made to the west's growing importance—but by then it was probably too late.

The Civil War was the final straw

The easy answer for why West Virginia split away from Virginia is always the Civil War and the issue of slavery. While that's certainly true, West Virginia's anti-slavery position was more about economics and power than morality—as was its decision to go its own way when Virginia voted to secede.

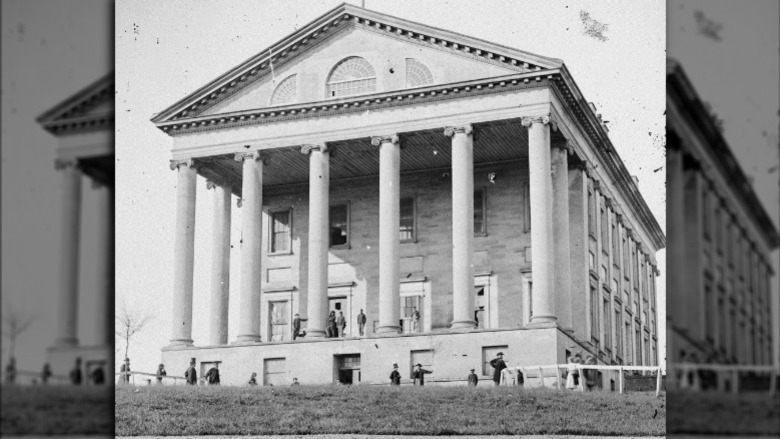

When the Civil War seemed inevitable, Virginia's government debated what to do, and ultimately voted to secede from the Union and join the Confederacy. But as "Old Dominion, New Commonwealth: A History of Virginia, 1607–2007" explains, the vote reflected the uneven balance of power in the state: 85% of the "secede" vote came from the wealthy landowners (and slave-owners) in the east, while Discover Richmond reports that two-thirds of the votes against came from the western counties.

The west's inability to affect the secession vote was the final humiliation, and almost immediately anti-secession conventions were organized in the western portion of the state in defiance of the state legislature. As the University of Richmond notes, West Virginia was decidedly more pro-Union than the rest of the state—especially in the counties that bordered Maryland and Washington, D.C., and their votes against secession were really the first step towards statehood.

The Union Army played a role

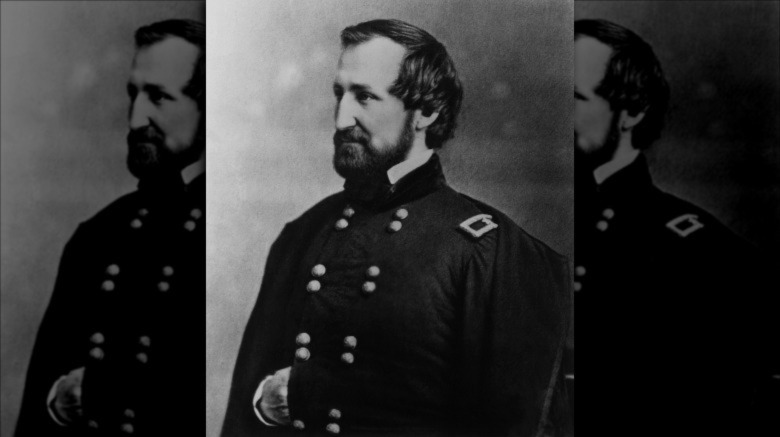

Although it's pretty clear that most of the people in what would become West Virginia were opposed to secession, anti-slavery to some extent, and very, very tired of being under the thumb of the wealthy eastern landowners, the population of West Virginia wasn't 100% in agreement. Although politicians in western Virginia moved quickly to call anti-secession conventions with an eye towards breaking away from the rest of the state, the outcome wasn't guaranteed. The final push may have come from the Union Army.

As noted by Warfare History Network, General William S. Rosecrans moved quickly to secure West Virginia for the Union, driving Confederate General John B. Floyd out. West Virginia remained under the control of the Union Army from that point forward, with about 40,000 troops in place there. While the troops weren't terribly effective against guerrilla groups in the mountains, the army definitely helped the nascent West Virginian government maintain control—and force statehood on their citizens. As noted by the Essential Civil War Curriculum, the army's presence allowed West Virginian politicians to more or less declare statehood without ever needing to take a vote—a vote that might not have succeeded. The Union Army also made it possible to include counties in West Virginia that Discover Richmond notes didn't actually want to split away from Virginia—but the Confederate Army wasn't there to enforce their will.