The History Of The Roman Empire's Favorite Condiment

When one imagines what the ancient Romans ate, it's difficult not to conjure up images in the mind of delicious Italian cuisine — al dente pasta covered in a marinara sauce with freshly grated Parmesan, oven-baked bread broken up and dipped in olive oil, and all washed down with a glass (or several) of red wine. Yet while some of these foods were frequently enjoyed by the Romans, such as bread, cheese, olive oil and wine, other staples of the modern Italian diet simply did not exist in the ancient Mediterranean, like tomatoes and pasta.

One food that was just as common to the Romans as wine and olive oil is something that most people would not think of today — a fermented fish sauce called garum. Yes, you read that right. It was a condiment made with fish that was allowed to ferment with lots of salt added to it. Without marinara, this savory sauce was the true ketchup of the Romans and was often used instead of salt because of its full umami flavor.

But if you thought the smell of fish cooked in the office microwave was bad, it's hard to imagine the extremely pungent stench of fish and salt sitting in the sun for weeks. It must have been worth it to make because garum started as a foreign delicacy imported from across the sea and then later was not only made in the villas of rich Romans but also the lower classes and even slaves started making their own versions. Just a recommendation for city folk — do not try to make this at home ... unless you want to piss off your neighbors.

The ancient origins of garum

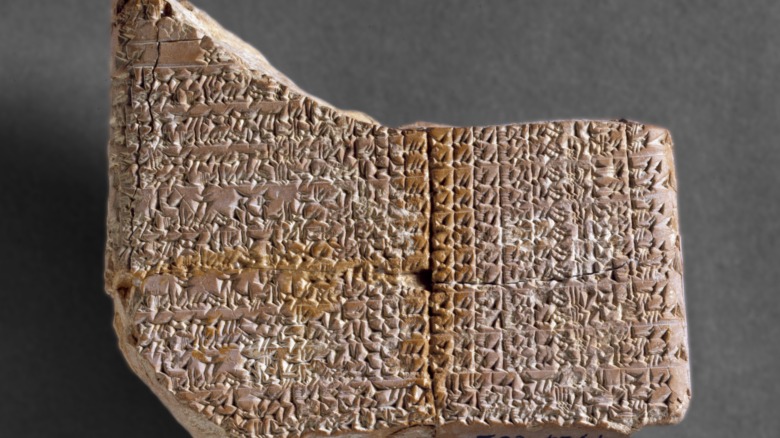

Long before Rome was little more than a village, ancient people in Mesopotamia were experimenting with salt and fish. According to Annalisa Marzano in her book, "Harvesting the Sea: The Exploitation of Marine Resources in the Roman Mediterranean," a Babylonian tablet of the 17th century B.C. describes a condiment made with pickled fish called "siqqu." Like garum, the fish sauce was fermented and often made with fish or shellfish, but the Babylonian version occasionally had its own weird ingredient — grasshoppers.

Possibly as early as the seventh century B.C., fish salting facilities were made along the northern coasts of the Black Sea. The Greeks slowly began to establish colonies in the region around this time, so they adopted the practice. Over time, a small industry gradually emerged amongst the Greeks, who then spread their salt-fish products throughout the Mediterranean Sea over the next 200 years. But while the Greeks were very active in the eastern half of the region, it was the Carthaginians who made fermented fish sauce popular in the western Mediterranean.

The Greeks may have gotten garum from the Babylonians, or figured out how to make it on their own, but some historians think it might have come from the far East. In A.D. 2010, a garum container from the disaster at Pompeii was examined by a group of researchers. After analyzing a sample of the ancient condiment, they found that it had the same taste profile as fish sauce made in Southeast Asia today. That is not proof of its origins but still fascinating.

The Greeks and Carthaginians introduced garum to the Romans

The Greeks may have started the salt fishing industry in the Mediterranean, but the Carthaginians were well on there way to surpassing them in the quality of their products. By the late fifth century B.C., a large amount of the garum and salt-fish goods in Greece came from the Carthaginian colonies of Spain, says Robert Curtis in his book, "Garum and Salsamenta: Production and Commerce in Materia Medica."

After the Romans entered the mix, salt-fish products became one of the most popular trade goods throughout the Mediterranean in the second century B.C. It is very likely that the Romans initially got garum from the Greeks, since the Latin term comes from the Greek word gáron. But even though the names were similar, the Romans may have used different methods and probably different fish to make their garum.

The Romans also took over or established many fish salting facilities in Spain and northern Africa after conquering the Carthaginian territories. Over time, these places developed into the centers of garum production for the Roman Empire. So, it would not be unreasonable to say the Carthaginians probably had more influence on the Roman fish sauce industry than the Greeks did overall.

The first garum of the Romans

Roman salt-fish products may have been exported out of Italy from Cosa as early as the third century B.C., says Annalisa Marzano. But fish salting facilities did not become more common among the Romans until the first century B.C., so it took a while for the Romans to get used to the pungent sauce, or at least like it enough to want to make it themselves.

According to Encyclopaedia Romana, the earliest explanation on how to make garum was written in the "Astronomica" by Manilius of the first century A.D. This specific recipe says that only the blood of tuna fish was mixed with salt to make a sauce that he called "a relish to the palate." But even though this recipe only used fish blood, other Roman writers just mention the organs, chunks of fish flesh, or combinations of all three, so there were several ways to make the condiment they all referred to as garum.

Regardless of the different varieties, the popularity of the fish sauce skyrocketed at this time across the empire. For the next 200 years, garum production got to the highest level it would ever reach in the entire history of the Mediterranean due to the love the Romans had for the condiment.

How the Romans made fermented fish sauce

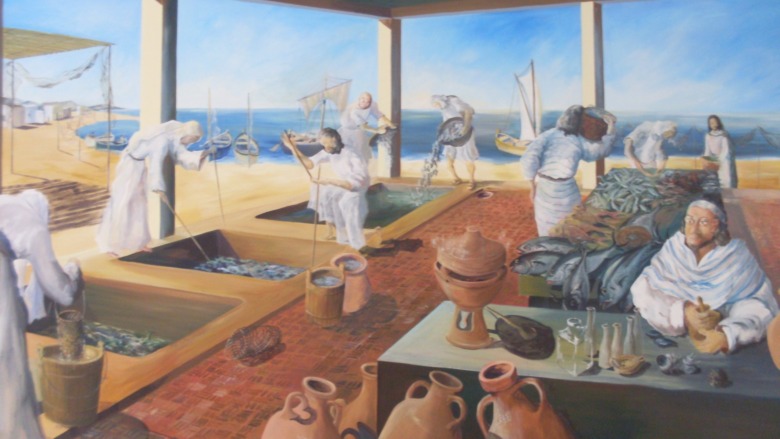

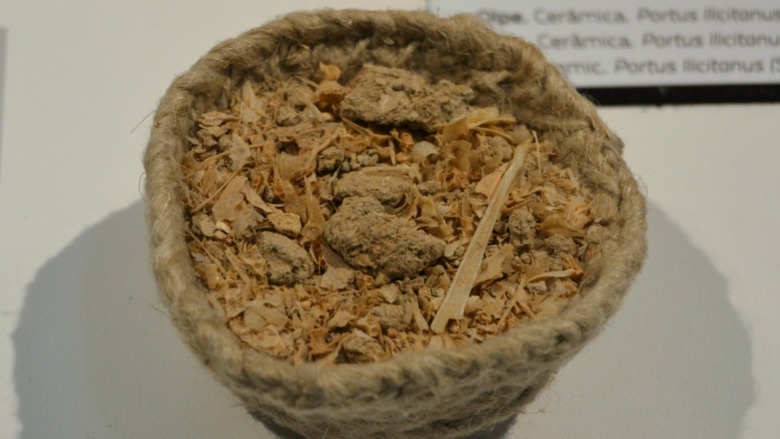

The Romans used different methods to make garum, but here is a basic recipe for how it was done. First, a layer of fish blood, guts, or pieces were placed in a container — the fish was often tuna, mackerel, sardines, and anchovies, yet salmon, red mullet, prawns, oysters, and other sea creatures could also be used instead, says Invicta. If small enough, the whole fish was used, but larger fish were cut up into pieces. A layer of salt around two fingers thick was placed on top, followed by another layer of fish, then one of salt, and so on until the container was filled, says Robert Curtis.

After a week of sitting in the sun, the fish parts fermented in the brine, but the salt prevented it from putrefying. After 20 days of mixing, the sauce was strained through a basket to take out the chunks, and the remaining liquid was the prized condiment that was amber in color.

To either improve the flavor of garum or make further variations, other ingredients were sometimes added to the fish sauce recipe as well, including oregano, dill, coriander, fennel, celery, or mint, says PBS. When used, these spices and herbs were added in between the layers of salt and fish before the fermentation process.

According to NPR, the Romans used enough salt so that it was about 15% of the mixture. This not only accentuated the umami flavor of the sauce, making it richer and fuller, but it also allowed it retain much of its nutritional content, especially for protein, says World History Encyclopedia.

Garum for the Roman aristocracy

Let's be real, the fishy condiment was just for the rich at first, and they could not get enough of it. In the first and second centuries A.D., garum became so popular among wealthy Romans that they began to make the sauce in their villas, so they did not have to keep importing it, says Robert Curtis. Luckily, their homes were so large that they could feed this need without stinking up the place too much.

Garum was also praised several times in the Roman literature of the upper classes, such as in the writing of Pliny the Elder and Martial. The first described garum as an "exquisite liquid" that was "so pleasant that it can be drunk" (via World History Encyclopedia) And Martial once wrote, "accept this exquisite garum, a precious gift made with the first blood spilled from a living mackerel" (via PBS).

However, garum was certainly not loved by all. In a scathing review of the fish sauce, Seneca called it "poisonous fish" which "burns up the stomach with its putrefaction." And even though Martial certainly liked the stuff, he once joked that you would not want to make out with a woman who has eaten six servings of it.

Roman use of garum

In the ancient Roman cookbook of Apicius from the first century A.D., the "De Re Coquinaria," garum is suggested far more often than salt and is used in almost every recipe. According to Robert Curtis, garum was in 350 of the recipes, while salt was only used in 31. But even though garum was more expensive than salt, the recipes were meant for the wealthy who were able to afford it.

And wealthy Romans put fish sauce on almost everything, from meat to eggs, bread, vegetables, and even fruit, honey cakes, or other fish. One of the most popular sausages in the ancient world, "lucanica," was improved upon by adding garum for its unique salty taste.

Garum factories spread throughout the empire

The best garum of the Roman Empire came from Spain, Portugal, and western Morocco, but other major producers of the fish sauce were in Libya, Asia Minor, the Italian cities of Pompeii and Cosa near Naples, the island of Sicily and southern France, says Invicta. According to World History Encyclopedia, the largest garum facility discovered so far is located at Lixus (in modern-day Morocco). It consisted of 10 factories and could produce over 260,000 gallons when the largest olive oil factory could only make a tenth of that amount.

Regardless of the size of that one factory though, the wine and olive oil industries were much larger than the fish sauce industry overall. However, garum was not limited to a specific climate like grapes and olives, so it could be made wherever there was salt and fish. The Romans of Britain definitely bought fish sauce from Spain, but they may have built their own factories at London, Lincoln and York. Though whenever garum was made in large quantities throughout the provinces, facilities sometimes had to be shut down temporarily by governors when the stench became unbearable.

How a garum manufacturer lived and worked

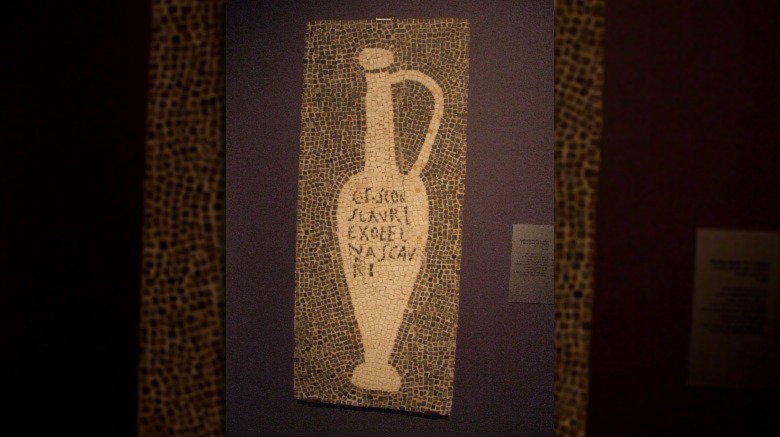

The volcanic eruption of 79 B.C. preserved the ancient city of Pompeii. Archaeologists have uncovered a huge amount of information about the Romans from this city, including much about the life of a garum manufacturer named Aulus Umbricius Scaurus. According to Mary Beard in her book, "The Fires of Vesuvius: Pompeii Lost and Found," Scaurus was one of the most successful fish sauce producers and exporters in the first century A.D.

Scaurus was originally a freedman who actually managed to become rich enough to buy his own retail shops, as well as live in a giant home with three reception halls and a gorgeous view that overlooked the sea. The home was also decorated with mosaic art that promoted his business and displayed salt-fish products. But it did not end there. Scaurus eventually gained so much wealth and respect for his family that he could help his son win an important local election. Then his son ended up being so successful that a statue of him was made for the city forum. An impressive feat for the son of a freedman.

Scaurus also gave his own employees the opportunity to shine as well. At least two of his former slaves were allowed to run their own workshops that sold garum in jars that were labeled "The manufactory of Aulus Umbricius Abascantus" or "The manufactory of Aulus Umbricius Agathopus." Scaurus still owned the entire facility the workshops were in.

Different types of Roman fish sauces

Even though garum was the term used by the Romans the most for fish sauces, they also used other words to describe different variations as well. Two of the most common of these other versions were called "allec" and "muria." World History Encyclopedia says that "allec" was the leftover pastelike sediment remaining after the fermented garum was strained through a basket. Similarly, the leftover brine from salting the fish was called "muria." Plus, sometimes garum was mixed with other liquids to create new condiments, like with wine to make "oenogarum" or vinegar to make "oxygarum."

Some fish sauces became so well known due to the quality of their ingredients that they were seen as highly recognized brands, says Invicta. According to Pliny the Elder, the best fish sauce of his time was the "garum sociorum" from southern Spain. Another so-called brand of the condiment included "garum scombri," which was made with mackerel, roe, and fish blood. There was even a kosher version called "garum castimoniarum" meant for Jews living in the Roman Empire. This garum was strictly made only with sea creatures that had fins and scales.

Jars labeled "garum castimoniarum" have been discovered all over Italy, meaning that the unique fish sauce was readily available to customers for this niche market. "Garum sociorum" was the most famous brand yet was far more rare because of its high price. In A.D. 79, 12 pints of this delicacy could be sold for as much as 1,000 sesterces, which was enough to buy 2,000 loaves of bread.

Fish sauces for the lower classes

Eventually, garum became so popular throughout the empire that less expensive versions emerged, which the lower classes could finally afford. Especially by A.D. 301, many could afford fish sauces and some became similar in price to something like honey, says Encyclopaedia Romana. Salt was also so cheap in the empire that most people living near the coasts of the Mediterranean Sea could easily buy fish sauce or make their own. Even slaves began to collect fish scraps in order to make a cheap version of the condiment.

According to World History Encyclopedia, garum became so widespread that it was considered a major source of protein and nutrients for the poor. Yet, the cheapest versions of fish sauce were more like the thicker "allec" puree than the amber colored liquid of high quality garum. "Garum scombri" was somewhere in the middle because even though it was expensive, the remains of it have still been found in even modest homes.

Garum gradually fades away into obscurity

After the constant warfare and political instability of the third century A.D., much of the garum production in Spain stopped, says Robert Curtis. The remaining production shifted primarily to North Africa for a time, but when the western half of the empire collapsed in the fifth century A.D., it almost died out completely. By A.D. 500, the people living in the former Roman Empire were already abandoning the culture of the old ruling elite. In his "De Obseruatione Ciborum," the Greek physician, Anthimus, bluntly stated "we ban the use of fish sauce from every culinary role."

For others, abandoning garum was not a choice but rather a decision made out of necessity. According to NPR, after the Roman Empire fell, the several kingdoms that took its place put new taxes on salt. Previously, in the empire, salt was a cheap commodity, but the new taxes made it much more expensive and also made it more difficult to make garum. Plus, without the Roman navy patrolling the waters, pirates began infesting the Mediterranean Sea once again. They raided the vulnerable coasts where fish sauces were produced and killed off much of what was left of the industry.

But garum was not completely gone from history. Later in the sixth century A.D., the bishop of Tours wrote that 70 vessels of fish sauce were stolen from the port of Massilia, says Sally Grainger. One of the last times fish sauce was mentioned was by Liutprand of Cremona in the 10th century A.D., saying it had a resurgence in popularity for the Byzantines (eastern Romans), though this was briefly before it faded out of the Middle Ages.

Fish sauces in the world today

Fermented fish sauce sounds super weird when you say it out loud, but it's not really that strange when you think about it. Worcestershire sauce is made with anchovies, and tons of people love the salty, umami flavor of soy sauce, which is basically a vegetarian version of fish sauce. In fact, fish sauces were popular in Japan, Korea, and parts of China until they were replaced by soy sauce in the 14th century A.D., says World History Encyclopedia.

In southeast Asia, fish sauces never fell out of fashion and are still a major part of all cuisines in the region, including "nuoc mam" in Vietnam, "nam pla" in Thailand, and "tuk trey" in Cambodia, says Invicta, along with similar condiments in Lao, Myanmar, and the Philippines.

In the Mediterranean, there is one final fish sauce from the past that is still made to this day. This modern version of garum is called "colatura di alici" and made in southwest Italy.