The Untold Truth Of Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia is some of the most hallowed land in America. Thousands upon thousands of military members and veterans have been laid to rest there over the past century and a half, and more are interred almost every day. It's a great honor, and many famous veterans including presidents and astronauts are buried there, as well as those who, in death, have no names.

Every Memorial Day, there are pictures of families grieving and remembering among the iconic rows of small white crosses and other gravestones. And every year, thousands of people with no connection to the cemetery visit to pay their respects.

While everything seems ordered and sacred on the surface, there's actually a lot of unexpected history behind how the cemetery came to be, how it's developed over the years, and found itself involved in controversies even to this day. This is the untold truth of Arlington National Cemetery.

Robert E. Lee lived on the land that is now the cemetery

The land that Arlington National Cemetery now sits on had a storied history long before it became the resting ground for thousands of military members. According to Real Clear History, it was owned by Martha Washington's only grandson (through her first husband). George Washington Parke Custis lost his father in the American Revolution shortly after his birth, and his namesake, the original George Washington, adopted him once the future president married Martha.

Custis got his inheritance from his birth father's estate when he turned 21, and it included 1,100 acres in and around Arlington, Virginia. He built a large mansion, and when he died, it went to his only surviving child, Mary Anna. So it is fitting that this house, that is still there today, has a connection to the first president and commander in chief of the United States

Or it would, if it weren't for who Mary Anna picked as a husband — Robert E. Lee. Once the Civil War started, Virginia seceded, and Lee signed up to fight for the South, Mary Anna decided being so close to Washington, D.C. was a bad idea and fled her house. Union forces quickly set up an encampment on the land, and when Quartermaster Gen. Montgomery C. Meigs started looking for a location for a national cemetery before the Civil War ended, the Lee's land was a perfect location. Plus it would send a message burying all those dead Union soldiers on the Confederate general's lawn.

Freed and escaped slaves lived on cemetery land

Arlington House and its plantation were run by slave labor, according to Arlington National Cemetery's official website. Just as burying the dead on the land was probably meant to be an insult to the South, in a similar way, part of the land was set aside to make sure formerly enslaved people had a place to live.

Called Freedman's Village, it was one of many of this type of settlements the U.S. government established during the Civil War. It was located on cemetery land and was only meant to be temporary, with the official site calling it essentially a refugee camp. But this Freedman's Village ended up not being short-lived. Instead, the residents turned it into "a unique and thriving community with schools, hospitals, churches and social services." From 1863 until the turn of the century, more than 1,100 former slaves lived on land given to them by the government, where they farmed and thrived. Of course, it was never going to be a happy ending to this story. In 1890, the government took the land back, and the residents were "turned out."

Many are also buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Section 27 was for "Contrabands," or former slaves. There are over 3,800 laid to rest there, under headstones that say simply "Civilian" or "Citizen." The very first burials were not segregated, and Black men and women were buried alongside white soldiers, but this would change within a few months.

So, so many people are buried there

Arlington National Cemetery is a big place. But the U.S. has also fought a lot of wars in the past 150 years, plus even the lucky soldiers get old and die eventually. So there are lots of dead bodies under that hallowed ground. Almost 400,000 as of 2021, and counting.

It makes sense that after you served your country you would want to be buried in "the most hallowed burial ground of our nation's fallen," as the official Arlington National Cemetery website describes itself. It is also one of the only cemeteries in the country that "offers graveside burials with military funeral honors with escort." If you are buried at Arlington, you know it's going to be the perfect event, other than being dead. That's why there are still anywhere from 27 to 30 funerals five days a week, with another six to eight on Saturdays.

That adds up quickly, and Star and Stripes says the cemetery is nearing capacity. The cemetery grounds have been expanded recently, but even with that additional space, it's expected there will be no more room in just a couple decades. It's easier to get in if you are cremated, since urns take up much less space than coffins, and restrictions about just who can be buried there at all have increased. One restriction put forward by veteran Sen. Tammy Duckworth is that presidents that did not serve in the military cannot be buried or interred there, nodding to her criticism of President Donald Trump.

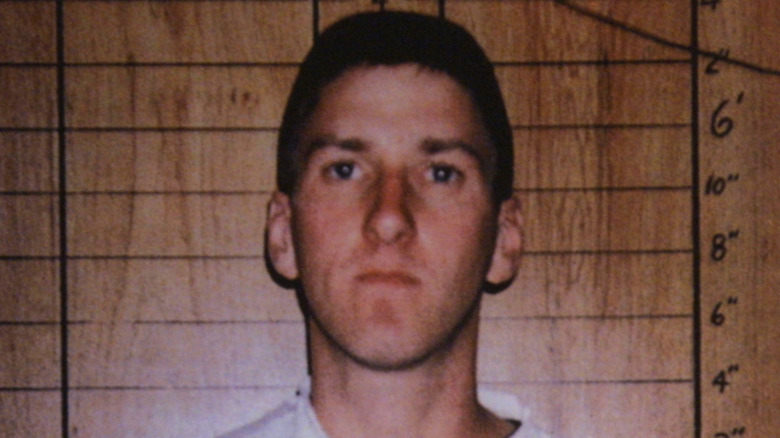

The law was changed to keep Timothy McVeigh from being buried there

It's astonishing to think about now, but at one point, Timothy McVeigh, the domestic terrorist responsible for the Oklahoma City Bombing in 1995 that killed 168 people — many of them children — qualified to be buried at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors. In fact, according to the Associated Press, he was extremely qualified, as a decorated veteran of the Gulf War. If he had claimed his right to be buried like any other soldier, it would have put the U.S. government in a very uncomfortable position.

To remedy this, within 10 days of McVeigh's death sentence being handed down for the terrorist attack, Congress began the process of changing the law to make an exception for soldiers and veterans who had committed really horrible crimes. A recent burial in a different military cemetery of a KKK member who was executed for lynching a Black teenager had drawn attention to the ridiculousness of honoring a horrific criminal in death, just because at one point they served. Then McVeigh's case just made the issue all the more pressing. The law was eventually changed, and murderers and rapists no longer qualified for military burial.

The Washington Post says that in 2013 the law was expanded, and now being in the ground already isn't a get-out clause for felons. If military cemeteries learn they have a criminal who was buried there before the 1997 law, the body is exhumed and moved elsewhere.

Notable burials at Arlington National Cemetery

Since Arlington National Cemetery is the place to be after death if you served your country in life, it has plenty of notable graves. There are those that are famous for their military exploits, as you would expect. According to Arlington National Cemetery Tours, Abner Doubleday fired the first shots defending Fort Sumter at the start of the Civil War (he did not, however, invent baseball.) Walter Reed might be more famous as the name of the medical center now, but the major did important work like confirming people got yellow fever from mosquitoes.

Important political figures buried there include President William Howard Taft, whose achievements are so numerous that the tour's website only mentions his invention of the seventh inning stretch and the tradition of presidents throwing out the first pitch in baseball. Thurgood Marshall, who successfully argued Brown vs. Board of Education before the Supreme Court before becoming the first African American justice himself, is also buried there.

There's plenty of adrenalin junkies as well, including the boxer Joe Louis, Robert Peary, the first man to reach the North Pole, and Pete Conrad, astronaut and third man to walk on the moon.

Arlington is also lousy with Kennedys. Assassinated president John F. Kennedy is buried there, his grave famously marked by an eternal flame. His wife, Jacqueline Kennedy, joined him after her death. And former attorney general of the United States Robert F. Kennedy is located adjacent to his brother, although in a much simpler grave.

There are hundreds of Confederate soldiers buried in Arlington National Cemetery

Considering Arlington National Cemetery only exists because of the Civil War, and was (possibly) meant to stick it to Gen. Robert E. Lee and the South, it's surprising that hundreds of Confederate soldiers are buried there. But for decades, this was more out of necessity than any sense of a united country.

Confederate graves were dotted about the cemetery, but according to its official site, grieving family members of those soldiers were not allowed to decorate the graves, or in some cases even enter the cemetery to mourn. In the later half of the 1800s, while the North and South might be united again, they still weren't playing nice.

Then the Spanish-American War happened. Uniting against a common foe finally allowed the two factions of the country to let bygones be bygones, at least when it came to Arlington. In 1900, Congress set aside part of the cemetery specifically for Confederate soldiers. The bodies of 482 rebels — including 58 of their wives, 15 civilians, and a dozen unidentified remains — were disinterred from graves in the surrounding area and reunited in Arlington. Unlike the rounded headstones in other sections, the Confederate gravestone all have pointed tops, and a legend says it's to "keep Yankees from sitting on them." The United Daughters of the Confederacy paid for a monument to their dead, which was sculpted by Moses Ezekiel, himself a Confederate veteran. (He was later buried at the base of his own statue.)

The first person buried on the land was a woman

Even though the military was made up mostly of men for much of Arlington National Cemetery's existence, Jackie Kennedy is far from the only woman buried there. In fact, according to The Liz Library, the first known person ever laid to rest on land that would become Arlington was named Mary Randolph, author of the late-18th century bestselling book, "The Virginia Housewife," and cousin of Robert E. Lee's wife Mary Anna, who inherited the land.

Many notable women followed, and while some are there because of the military service of their husbands, most of them seem to have achieved a significant first. Barbara Allen Rainey was the first female pilot in U.S. Navy history. Dr. Anita Newcomb McGee was the first woman Army surgeon. Mary Roberts Rinehart was America's first woman war correspondent during World War I. Vinnie Ream was the first woman artist commissioned by the federal government, who, at just 18, sculpted a statue of Abraham Lincoln that now sits in the Capitol. Grace Hopper pioneered computing and was the first person to use the word "bug" to describe a computer issue.

According to the official website, section 21 of Arlington National Cemetery is known as "the Nurses Section." At least 653 female nurses are buried there, their sacrifices honored by "The Spirit of Nursing" statue. It was requested by Franklin Roosevelt prior to World War II and was created by Frances Rich, who would go on to join the Navy WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service) during WWII.

The bodies in the Tomb of the Unknowns

It's an unfortunate reality that war is hell, and part of that hell is sometimes you end up with bodies and you have no way to identify them. These unknown soldiers often didn't get the burials their rank and service should have entitled them too, not to mention there was no closure for their families.

World War I saw so many unknown dead, many of whom were left in the country they died in and not repatriated, that two years to the day after the war ended, France and Great Britain each buried one unknown soldier. According to Arlington National Cemetery's official website, this was meant to symbolize all the unknowns, and families could grieve there, because, theoretically, it might be their loved one. The U.S. decided this was a good idea, and a month later a congressman proposed the country do something similar.

A year later, four bodies were dug up in Europe and their caskets presented to Sgt. Edward F. Younger. He selected one, which became the first body in the Tomb of the Unknowns. After the Korean War, an unknown was added from both that conflict and World War II, with the specific individuals decided through similar ceremonies. Advances in technology meant only one recovered body from the Vietnam War was unidentified by the time it was interred in 1984, but it was later revealed to be 1st Lt. Michael Joseph Blassie and removed. That crypt remains empty. (Civil War unknowns have their own memorial, with 2,111 buried beneath it.)

The guards of the Tomb of the Unknowns

The military guard of the Tomb of the Unknowns is almost as famous as the tomb itself. And ABC News shares a shocking fact about those who do the job — "Since April 6, 1948, Tomb Sentinels from the Army's 3rd Infantry Regiment's 'The Old Guard' have guarded the Tomb for 24 hours a day, 365 days a year regardless of the weather." Even more impressively, they volunteer for the position. While that can mean being snapped by tons of tourists who come to see the changing of the guard, it also means being there through hellish weather. During Hurricane Sandy, one sentinel stood watch in the crazy wind and rain for 23 hours straight — again, something he volunteered for.

While the specifics of the watch are less formal during ridiculous weather like that, during normal times, the watch is extremely regimented. "Walking the mat" is probably the most famous part of the cycle. It involves the sentinels marching "in front of the tomb for 21 paces, then face north to stand at attention for 21 seconds before marching 21 paces in the other direction." The cycle of 21's is meant to represent the highest military honor, the 21-gun salute.

Then there is the Changing of the Guard, which is just as stylized. According to the official website, it involves the sentinel on duty being relieved by a new one, but not before their commanding officer "conducts a detailed white-glove inspection" of the new sentinel's rifle.

The Arlington National Cemetery mismanagement controversy

Considering how important honoring the fallen is to the U.S. military, you would think that those in charge of running Arlington National Cemetery, arguably the most hallowed cemetery in America, would take it really seriously. Any small mistakes would be corrected immediately, and each body and its resting place treated with the utmost care.

Sorry to burst that bubble, but in 2010, things hit the fan at Arlington. An investigation discovered horrific mismanagement, which affected grieving families. It turned out if you'd been going to a grave to mourn your dead daughter or husband who just died in Iraq or Afghanistan, they might not actually be in the one marked as theirs. They might not even be in the right general area.

According to CNN, the investigation found hundreds of graves were mislabeled. In a follow up a year later, The Washington Post said the problems at Arlington went much further — "a dysfunctional management system, millions wasted on information technology contracts that produced useless results, misplaced and misidentified remains, and at least four cases in which crematory urns had been dug up and dumped in a dirt pile." Another "mass grave" of eight cremated remains was discovered, and at least one "grave" was actually empty. On top of all this, it looked like management knew about these issues and falsified records in order to cover up the mistakes instead of fixing them. The cemetery is now under new management, as you'd expect.

Wreaths Across America manages to be controversial

According to the official story of how Wreaths Across America began, it was just a kind gesture by a small family company, Worcester Wreath, who had some leftover stock after Christmas, so they sent them to Arlington National Cemetery to decorate the graves and honor the soldiers. In the last three decades, it became a major event, now run by the Wreaths Across America non-profit.

But if you go to their website to read this beautiful story, you might find it odd that at the top of the page it says, "Please note, anyone wishing to read about the difference between Wreaths Across America, the national non-profit organization and Worcester Wreath Company, can read more here." Following the supplied link takes you to a very long and very defensive explanation of how the company and the non-profit are so very different.

That's because there appears to be a huge conflict of interest here. According to the Wall Street Journal, the charity and company are run by the same people, yet the charity buys its wreaths exclusively from that company, using donated funds. The charity had bought $25 million in product from the Worcester Wreath Co. by 2015. And it's not like that was nothing to this major wreath conglomerate — 75% to 80% of the family company's annual business comes from the charity they also run. While sketchy, it doesn't appear to be breaking any laws, and the Wreaths Across America program continues.