Rules British Ladies-In-Waiting Must Follow

A lady-in-waiting is a woman who attends to the various needs of female members of a royal family. There are different types of ladies-in-waiting for the British royal family, and these ladies were historically daughters of nobles and other important figures in British society, though this is not necessarily true today. The position used to be a bona fide career path, as women would take salaries and, if they performed well, be guaranteed employment for life in the form of royal service. However, things have changed, and today the ladies are simply friends of the royals. They still tend to come from society backgrounds, as the position is unpaid and grants the woman close contact with royal business.

The role of lady-in-waiting has historically been quite political. Even outside of the fact that ladies were appointed in a show of accepted patronage by different nobles, they have been used to make statements and break alliances. As they are a direct representation of the queen's ability to rule, events where the ladies have behaved poorly — such as during a visit from a Mantuan envoy in 1520 during which the ladies apparently drank too much — can affect political relationships between two states. For some intra-state drama, see the event called the Bedchamber Crisis, in which ladies-in-waiting were used as pawns in the fall of Whig dominance to the Tories (via the BBC). But other than these large events, what do ladies-in-waiting do on a day-to-day basis? Here are some rules that British ladies-in-waiting must follow.

Know your rank

A lady of the bedchamber is the highest general category of lady-in-waiting. These were historically wives (or widows) of other nobles. The highest lady of the bedchamber, and thereby single highest lady-in-waiting, is the mistress of the robes. She is always a duchess and has many duties, including scheduling the rotations of all the other ladies-in-waiting. Next in line is the woman of the bedchamber, who is responsible for making the queen's social calendar, and (at least historically) helping her bathe and dress.

Maids of honour are next in the hierarchy. These are essentially unmarried ladies, though with their inferior unmarried status comes inferior rank and duties. Lucky (or, some might say, advantageous) maids could marry up and find themselves in a very high lady-in-waiting position — on top of receiving a £1,000 marriage gift (£134,000 today) from Queen Victoria herself during her reign.

Lastly, there are extra ladies of every category. According to an 1895 edition of The Strand Magazine, these are not permanent members of the court but rather are called in when another lady cannot perform her duties. Additionally, the queen's female "close relations," such as cousins, would live in the palace and wait on her. These relatives were typically married, and all ranked higher than any lady-in-waiting.

Breaking with this traditional system, Queen Elizabeth II has only five ladies-in-waiting. While she has both a mistress of the robes and a woman of the bedchamber, their duties are not so strictly defined as they were during previous eras.

Act as the queen's companion

A main duty of a lady-in-waiting is to be a companion to the queen in public and in private. This role was especially important before the modern era, when the royal family was not allowed to consort with anyone below a certain rank, leaving naturally formed friendships mostly out of the question (via Tudor Times).

Enter: the queen's flocks of ladies-in-waiting. Such companionship was largely transactional, with the ladies tending to the queen more like servants than friends, in return being granted a place in the upper echelons of society. According to Allison Weir in her book "Elizabeth of York," ladies to the queen had to have "a vigilant and reverent respect and eye" so that they might anticipate their mistress' needs. However, some genuine friendships did blossom out of the position. In a letter to one of her ladies-in-waiting, Anne Boleyn (the second queen of Henry the VIII, who had herself been a lady-in-waiting to his first queen before her banishment!) wrote, "...I loved you a great deal more than I made feign for ... assuredly, next mine own mother I know no woman alive that I love better."

In the modern day, when the queen has the ability to appoint her ladies (a task formerly performed by the king), they tend to be chosen from the pool of friends she is already close with. Most of these women are independently wealthy and have royal titles, representing the small social sphere that the queen still socializes in. This allows the companionship task to feel much more natural.

Look decorous

As a group of ladies dressed to the nines and looking perfectly posh, the ladies-in-waiting can be an important visual symbol of respectability and proper conduct for the royal family. They are tasked with behaving well because they are direct reflections of the capability of the queen and her court.

In Tudor times, the ladies of the queen's court spent significant amounts of time crafting beautiful clothing. All of Elizabeth I's ladies were skilled in needlework and were expected to dress in their lavish creations, as well as those created by professionals. The Tudors had clothing standards for each station of lady, and "their dress was to reflect their employer's status rather than their families'." As evidence of these strict rules of dress, Jane Seymour (queen from 1536-7) once told a lady-in-waiting that her girdle embroidered with 120 pearls was not good enough to be worn in the queen's presence.

During Elizabethan times, it was increasingly important for ladies-in-waiting to be hygienic. To "look clean and smell pleasant" was a display of status, as regular bathing with hot water, herbs, and fragrant oils was something only available to the rich. However, frequent bathing may have been more of a request than a reality (via historian Alison Weir). Beginning with Edward the IV but ending in the modern day, they were also required to be beautiful. According to the Tudors, a good-looking court would reflect well upon the queen and enhance her own beauty.

Live on the premises

This rule is mostly archaic, though it was at one point the strict law of the land. Most of the queen's ladies were required to stay on the premises during their waits, due to the fact that their assistance was needed with the most basic of tasks like using the restroom. Additionally, the Queen acted as loco parentis (legal parent/guardian) of the maids, or unwed ladies-in-waiting, who attended her. This meant she was responsible for them learning how to run a household, as well as making sure they stayed well-behaved and chaste. To ensure their good behavior, the queen and her ladies stayed in separate quarters from the rest of the castle.

Taking advantage of their role as essentially parents, certain queens also ensured their ladies' actions reflected specific values. For example, Queen Katherine of Aragon would read her ladies religious texts nightly and "forbade any vain amusements" for her court. Her successor Anne Boleyn had her ladies sew clothing for the poor, worrying that too much idle time would cause them to stray from the path of righteousness (read: stray into the men's quarters).

Although most ladies-in-waiting do not live with the queen anymore, they are sometimes allowed to stay in Buckingham Palace or the royal apartments in London should their duties require it. According to The Independent, Elizabeth II's "top girl" Lady Susan Hussey has been living in the queen's Windsor Castle bubble since the start of the pandemic.

Dress and bathe the queen

Royals were not supposed to do anything themselves before the modern era. As a demonstration of this principle, British History Online lists the servants required to wash the queen's hands, including one to bring the water, one to set the water before her, one to pour it over her hands, and one to replace her gloves. Many of the most intimate daily tasks required specific ladies-in-waiting, sometimes referred to as "body servants." These were mostly the ladies of the bedchamber. Body servants were required to be of the highest ranks in society, due to their proximity to the queen in her intimate moments.

While today, British royals do much more for themselves, even Elizabeth, modern lady that she is, has a specific set of rules governing bathtime. Her attendants draw the bath for her, using a thermometer to ensure a precise temperature while making sure they maintain a specific water level. When aboard the royal train, she even has the train operator drive slowly during her morning bath so that the water sloshes less. Rather than having a lady serve her dressing needs, she has personal stylist Angela Kelly on the task. Kelly is responsible for making sure the queen looks proper and feels comfortable. Kelly revealed in her memoir that she even breaks in her majesty's shoes for her, saying, "... as we share the same shoe size it makes the most sense this way." Does it, though?

Entertain the queen

Entertaining the queen was one of the main duties of ladies-in-waiting back in the day. Queens relied on their close confidants to entertain their royal minds on a day-to-day basis since they only went out in public for large events. Because of this, ladies-in-waiting were required to have a skillset suitable for entertaining their mistress, such as playing instruments, dancing, and riding. Ladies were occasionally called to play games or even cards, which Elizabeth I famously loved after they came to Britain in the late 14th century (via historian Alison Weir). They would ride with her, stroll with her in her gardens, and basically do whatever her whims directed at any given time.

While this rule isn't really in practice anymore, the queen's ladies still occasionally serve an entertainment purpose in her life. For instance, on Elizabeth II's first tour after her father's death, her lady-in-waiting Pamela Hicks accompanied her "so they could have a bit of a giggle." Lady Anne Glenconner, a childhood friend of the Windsors who served Elizabeth's sister Margaret, writes in her autobiography about being expected to deal with the princess' "royal moments," like "dog-paddling sideways so the breaststroking princess could continue a conversation" (via The New York Times). Now that's good service.

Help the queen use the lavatory

When we say royals weren't allowed to do anything for themselves, we truly mean anything. The Tudors actually had portable toilets, which were carted around by close confidants who also helped the royals undress. There were additional ladies responsible for disposing of waste in the chamber pot, and potentially even wiping the royals after their bowel movements (although this is currently up for debate). This position was called the groom of the stool, and it was invented by Henry VIII for his court, though equivalent female positions existed for the queen's service. According to the BBC's History Extra, the groom of the stool was a highly regarded position often given to the closest friends of the monarchs.

The position changed somewhat under Elizabeth I — her grooming duties became folded into the role of woman of the bedchamber — and is said to have been given up by Queen Mary, although there are rumors that it still exists. Evidence points to these rumors being false, especially given that no one is allowed to know when Elizabeth II is going to the restroom — she's very private.

Manage social events

As one of the most important figures in Europe, the queen has an incredibly busy social calendar. Historically, she entrusted her social life to the woman of the bedchamber, a society woman herself who knew of the most elite and proper events for where her mistress should be spotted. Even though the queen had control over her social gatherings, "Her life was governed by ceremonial and ritual," and the task necessitated a servant to carry out her wishes.

While the queen has additional help these days in planning her calendar, such as from her press secretary, her woman of the bedchamber is still consulted about many social events. Additionally, she is to remain by the queen's side at many social functions and has a variety of event-day duties. The woman of the bedchamber will collect flowers from onlookers at public events, as well as interact with the queen's crowd of roaring fans. She will even sometimes attend events on behalf of the royal family should a monarch not be able to attend, according to Tatler.

Handle correspondences

Queen Elizabeth II likes to answer a few pieces of fan mail each day, but the remaining lot (sometimes around 300 a day!) are answered by a lady-in-waiting. Their job includes responding to each letter kindly and politely, as well as ensuring that any dedicated countrymen get noticed by the queen.

If a lady-in-waiting flags your correspondence, you may receive a personal letter from the queen herself. This happened to a man who took up his late grandfather's tradition of sending the palace an annual Christmas card. According to The Independent, he received a personal letter from the queen giving her condolences. She wrote: "When I received a letter from a different Simes this Christmas, I instructed my office to research your grandfather's whereabouts. Therefore it is with much sadness, I have learned of his passing and extend my condolences to you and your family."

Additionally, one of the queen's ladies-in-waiting flagged down a wordsearch, made expressly for the queen by a little boy. The lady made sure it made it to her majesty and made sure to thank him for his "kind letter, and for the puzzle." The lady-in-waiting's careful attention to palace correspondence allows the queen to build relationships with her subjects, making them feel supported by their monarch and in turn boosting the queen's public image.

Understand that you will not get paid

Being a lady these days is more a symbolic honor than a paid job. You benefit by being near the royal family and gaining status but receive no financial compensation for your duties. Ladies do, however, receive stipends to cover the extensive travel and lavish clothing involved with the position. Occasionally, they might even receive high honors like becoming members of the exclusive Royal Victorian Order. Rebecca Deacon received the exclusive membership in 2017 as a recognition of her service, and Lady Susan Hussey became the organization's dames grand cross, the highest possible rank, in 2013.

Historically, ladies-in-waiting received salaries in addition to room and board. According to historian Alison Weir, Queen Elizabeth I's highest-paid female attendant received a salary of £33.6s.8d. (£16,300 in today's figures). Additionally, her maids each got £6.13s.4d. (£3,300), and the "sixteen gentlewomen" that waited on her received £3.6s.8d. (£1,620). By the early 1700s, salaries for women of the bedchamber were £500 (£60,000). The clothing necessary for the job was gifted to them every Christmas and Whitsun (the British name for Pentecost), and they received special dresses for royal events like coronations and funerals. They also received regular gifts from the king and queen, such as at New Years, Christmas, and Whitsun. Additionally, all maids received the title of "the honourable" in exchange for their service. The position was seen as a bona fide career rather than the glamorous volunteer position that it has morphed into today.

Work on rotation

Although there are many ladies-in-waiting, only a few are on call at any given time, and their rotations are known as "waits." These waits are decided upon by the queen and arranged by the mistress of the robes. According to The Strand Magazine, during Queen Victoria's court, ladies of the bedchamber had two to three waits a year, each lasting 12 days to a month. Her women of the bedchamber had the same length waits, but slightly more, at three to four a year. Victoria's maids waited for a month at a time, for three to four months per year. Queen Elizabeth II's ladies serve standard time allotments regardless of station, being called into duty for two weeks at a time followed by a four-week vacation.

Different queens had different numbers of ladies-in-waiting in rotation at a time. For instance, Queen Victoria had just one lady of the bedchamber in rotation at once, pulling from her total of six. Katherine of Aragon, at one (brief) point, had 250 maids of honour alone, with who knows how many individual ladies waiting on her at once!

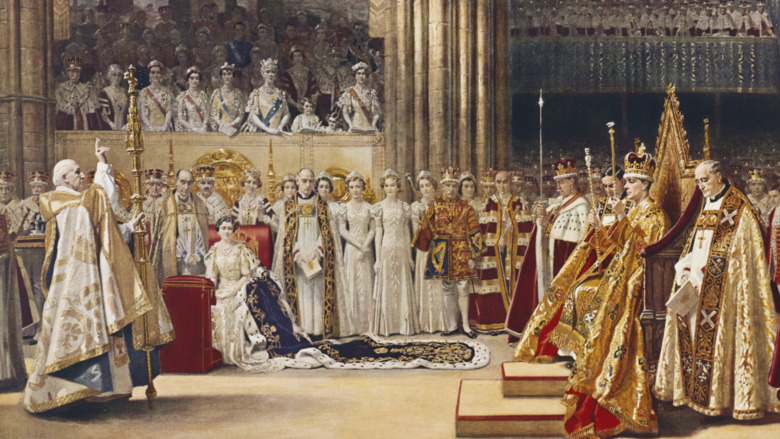

You might not always be needed

While any lady-in-waiting position is an honor to have, some are more necessary than others. In fact, many positions today are more ceremonial than anything, with ladies only being called in for big events like state dinners or coronations. This is especially true in the modern era, as the royal family now hires staff for many of the duties previously given to ladies-in-waiting. Some ladies-in-waiting act more like friends, simply taking on ceremonial duties like public appearances. Others act more like hired secretaries, managing the queen's calendar and handling other affairs (via Slate).

For instance, while Lady Susan Hussey, Queen Elizabeth II's "most loyal lady-in-waiting," does have some administrative duties around the palace, she is typically only present at important events. She attends occasions on the queen's behalf when the monarch is unavailable, stands by her side at state events like the Diamond Jubilee, and even rode in the car with her to Prince Phillip's funeral. Even Ann Fortune FitzRoy, the current mistress of the robes and therefore the highest-ranking lady, is only needed for ceremonial occasions.

You can't retire

Once a lady, always a lady! If you are appointed to such an honorable position, you may change ranks (historically, this happened by marriage to a higher-ranking official), but you do not forgo your duties. Not only was being a lady-in-waiting effectively a career path, representing a rare way for noble women to secure some personal finances, but continued loyalty to the reigning family in the form of service was expected. Suspicions to the contrary could result in social ostracization or even banishment.

Even though the position looks very different In the modern day, you are still not expected to retire. The queen's ladies-in-waiting have taken this rule quite seriously. Her top attendant, Lady Susan Hussey, is still engaging in her duties at the ripe old age of 81. So is Lady Ann Fortune FitzRoy at an astonishing 101. A few modern ladies have managed to retire, such as Rebecca Deacon. Deacon got permission from the queen in 2017 to forgo her duties, choosing instead to pivot to a new career and focus on her husband and newborn son, writes Royal Central. (Because several ladies-in-waiting are essentially secretaries in the modern era, Deacon is often referred to as such.)

Stay out of royal relationship drama

Alright, so this one is more of an unspoken rule, but it is nonetheless important. Several ladies-in-waiting have become mistresses to the king, a phenomenon for which King Henry VIII was notorious. Since Henry was apparently "often to be found 'feasting ladies' and enjoying their company," it is perhaps unsurprising that he promoted several ladies to the rank of queen. In fact, according to History, three of Henry's six wives were ladies-in-waiting to his previous queens. Another king with a fondness for the ladies was Edward III, whose love affair with his queen's lady, Alice Perrers, got her banished.

But ladies could face the wrath of queens as well as kings. Elizabeth I once had a love affair with the earl of Essex, and when he ran off with one of her ladies, she banned them both from court. The moral of the story: Don't go beyond the call of duty.