The Messed Up Truth About The 1950s Music Industry

Correction 2/28/22: A previous version of this article stated that slavery ended in 1863. With the ratification of the 13th amendment, slavery officially ended in the U.S. in 1865, not in 1863.

When the end of World War II was announced in 1945, it's easy to think that there was the global feeling of a weight lifted off the shoulders of the world ... and while there was, there was a lot of darkness that followed in the years afterwards.

Among those realities were broken families, soldiers suffering from untreated PTSD, alcoholism, and an era of familial violence that was hidden behind closed doors. It was bad, suggests the BBC, and that's the world that gave birth to a generation who revolutionized the music ... and who just wanted to dance.

While it's been endlessly debated, many historians believe that rock 'n' roll was born on March 3, 1951. That, says AV Club, is when Jackie Brenston and His Delta Cats recorded "Rocket 88," a song defined by the distorted sound of a broken amplifier — the first song of a new era. Radio and music would never be the same.

Within just a few short years, the airwaves were filled with Fats Domino, Bill Haley, Chuck Berry, Carl Perkins, Little Richard, Bo Diddley ... the list goes on and on. Music would never be the same, but behind those catchy tunes that got all the kids dancing, there were a lot of horrible things that artists went through ... all for the music.

Record companies cashed in — and didn't pay royalties

Starting with the birth of rock 'n' roll, the Belleville News-Democrat says record companies have done shady things to make sure they were rolling in the dough — while the artists who were doing all the work still struggled.

They give the example of Fred Parris. His name might not be a household one, but everyone knows his most famous song, "In the Still of the Night." Just that song sold somewhere around 10 million copies, and a decent contract should have given him somewhere in the neighborhood of $100,000 in royalties. (That's a little over $1 million in 2020.) He absolutely didn't get it, and instead, earned just $783.

Why? It's a complicated issue that boils down to race. Radio stations and record execs felt they needed a white face and voice to sell records, so many songs were covered by white artists, who paid a licensing fee, which sometimes went right into the pockets of the record company instead of the creators of the song. Pat Boone covered "Aint' That a Shame" from Fats Domino and "Tutti Frutti" from Little Richard in that way, for example. Little Richard didn't pull punches, saying, "When Pat Boone covered my record, I was mad, I wanted to get him. I said, 'I'm goin' to Nashville to find him.'"

Concerts were segregated

Slavery may have officially ended in 1865 in the U.S. with the 13th amendment, but then, there was the beginning of another era – Jim Crow. These new laws were meant to keep segregation in place, and in the 1950s, racial tensions definitely extended to the music scene.

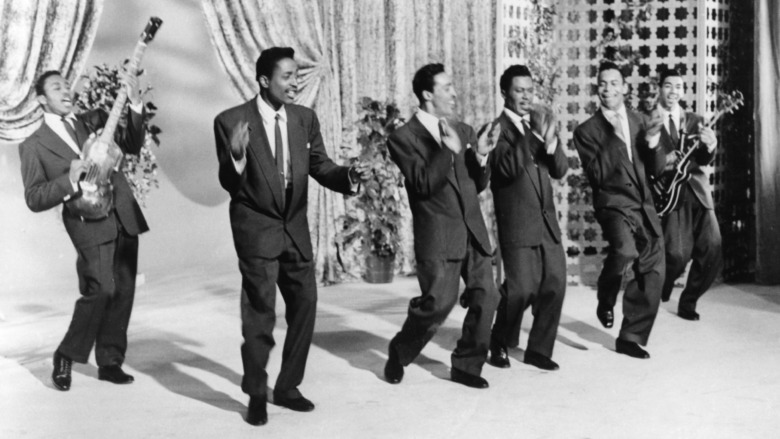

It's specifics that are really the most telling, and in 2017, Rolling Stone spoke to Terry Johnson of the Flamingos. He told a harrowing tale of a late '50s concert they gave in Birmingham, Alabama. When they arrived, they had a police escort. Johnson said, "The cops were up there making sure we did not look at any white person. It was a rule when we came in: 'I don't want to see any of you darkies looking at the white women out there. If you do, your ass is mine.'" It was far from the only concert where Black and white attendees were separated, and, yes, things sometimes turned violent.

When Jackie Wilson canceled a second, white-only show (after already playing a Black-only one before realizing a second had been scheduled), he and his crew were run out of town at gunpoint. It ended with the tires of Jesse Belvin's car blowing out — both he and his wife died in the following crash.

Then, there was a 1959 concert when Charles Neville (of Neville Brothers fame) played in the house band at the Dew Drop Inn, where three white women snuck into a Black-only show. New Orleans police arrested the women and beat them so badly they were hospitalized.

Some of the biggest performers still had to abide by Jim Crow laws

Black performers often found themselves at the mercy of Jim Crow laws, and the Flamingos' Terry Johnson recounted some incidents to Rolling Stone. Not only were they forced to sleep in their cars while they toured, but they weren't allowed in most restaurants. When they were, they were typically served rotten food.

In 2020, Billboard spoke to some pioneering artists of the 1950s and '60s about the discrimination faced while touring.

Martha Reeves explained, "We were happy, we were singing, we were joyful, we were away from home for the first time, youngsters on a magical show. But being met with the hatred, it was alarming — especially when the bus was being shot at." Singer Dee Dee Sharp had a similar experience. "I will never go back to Jackson, Mississippi, ever again. They actually stoned the bus. ... The Dovells [a white group on the same tour] covered my mother and I to keep the stones from coming into the bus."

And it wasn't just in the South. Leon Hughes Sr. of the Coasters recounted how they arrived at a tour date in Lincoln, Utah, and the promoter approached looking for the Coasters. When they responded that they were the Coasters, there was a brief argument about how they couldn't be — "I think they're white." — and the incident ended with them leaving town very quickly.

Record companies stole some of their biggest hit songs

What's the difference between "borrowing" and "stealing"? If your answer is, "They're spelled differently," then congratulations, you might just be the reincarnation of a 1950s record executive.

There's probably no better example of this than the early rock mega-hit "Hound Dog." Elvis Presley took it to the top of the Billboard Hot 100 in 1956, but according to The Washington Post, it had first been recorded by the blues singer Big Mama Thornton in 1952.

According to the Library of Congress, "Hound Dog" was first performed by Thornton and Johnny Otis. Writers Mike Stoller and Jerry Lieber had seen her perform and were inspired to write the song, which was cleaned up to take out some of the more inappropriately racist bits. Otis was given a song-writing credit and owned half the publishing rights, but once Presley had such a hit with it, they realized they didn't want to have to share. Otis recalled, "... they got greedy. They sued me in court. They won, they beat me out of it. I could have sent my kids to college, like they sent theirs."

As for Thornton? Music industry expert Eric Alper explained it this way (via Global News) — "Big Mama Thornton did not have lawyers. She didn't have a distribution network that can say to record stores, 'You've gotta pull Elvis' song ... She's left with breadcrumbs."

Chess Records bankrupted their talent

In 1989, The Washington Post made a huge announcement — MCA was going to be paying surviving rock 'n' roll veterans a boatload of money. And it was money that they should have received decades prior but hadn't. MCA had just acquired the back catalogues of Chess and Checker, and when they did a deep dive into financials amid a massive re-release program, things got sketchy.

The basics are this — Chess and Checker had a nasty habit of paying major artists like Bo Diddley and Muddy Waters a flat fee for their work. Then, whatever the records made, the record companies got ... and meanwhile, those same record companies were holding debts over their artists' head. How? By charging the artists "production" costs that needed to be repaid.

And it was a ton of money that was owed and never paid. Waters is just a single example. In 1986, his account was a whopping $56,000 in the negative. Also in 1986, he should have earned — but was never paid — $25,000 in royalties.

He wasn't the only one. Scott Cameron was an activist representing around 70 artists (and in some cases, their estates), who said that for many, this MCA payout was a first. Cameron said, "It's wonderful that all these Chess artists who, to my knowledge, never received a royalty check in their lives, are finally getting paid."

Performers were often forced into grueling schedules

When Buddy Holly died in a frozen Iowa field in 1959, he'd had seven songs hit the Top 40 in just a year, and — at only 22 years old — he was going places. He already had plans to start his own record label (after going through his own battle over royalties) but was so broke that he agreed to the Winter Dance Party tour.

The tour's powers-that-be clearly booked the gig with absolutely no regard for performers, and it was so bad that even before the fatal plane crash that claimed the lives of some of rock's most promising young artists, it was already known as the "Tour From Hell." The Star Tribune says that they were scheduled to play 11 shows in 11 days, with hundreds of miles in between gigs — in a converted school bus and temperatures of -30 Fahrenheit. That's so cold that the bus froze in the middle of Wisconsin. Holly's drummer realized how cold it was when his feet turned brown with frostbite.

They burned newspapers and took turns sharing a bottle of scotch (says Rolling Stone) until they were spotted by a trucker who alerted a local sheriff's deputy. It's no wonder that when tour organizers booked another show on their off day — 365 miles away — that the already flu-ridden musicians scrambled for a hired plane.

That day became widely known as The Day the Music Died.

The tragic death of Billie Holiday

When it comes to the 1950s music industry, it's possible to say that they looked out for their talent. It's possible to say it, sure, but it's 100% wrong — especially for those like Billie Holiday.

Holiday, says The Progressive, got the attention of Harry Anslinger — the fanatically racist commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics — when she refused to stop singing "Strange Fruit." (The song is a reference to lynchings.) In 1947, Anslinger's men framed her for buying heroin, and when she finished her 18-month jail sentence, she found that her "cabaret performer's license" wasn't going to be renewed — and that meant she couldn't perform anywhere that served alcohol.

Unable to return to her regular performances, she fell hard into depression and heroin. Fast forward to 1959, and she was already dying when she entered a hospital in New York — but still, she warned her family, "They're going to kill me. There's going to kill me in there. Don't let them."

Holiday began to respond to the treatment, until Anslinger dispatched some of his cronies to prevent doctors from continuing the methadone treatment that was working. She was dead in just a few days.

Lyrics about underage girls were A-Okay!

When this new thing called rock 'n' roll hit airwaves, it was pretty clear that the target audience was the era's teenagers. It followed, notes The Guardian, that many of the songs were ones that teens could relate to, and that involved things like experiencing love and infatuation for the first time — that's part of growing up. While some of the artists were age-appropriate (Buddy Holly released "Peggy Sue" in 1958, for example, when he was 22 and his drummer's girlfriend, the real Peggy Sue, was 18.)

The music of the '50s, argues journalist Charles Shaar Murray, legitimized older men crooning about younger women — and at the time, it was kind of a win for everyone. Teens felt like this was a kind of music they could relate to, and — Murray says — they got "an opportunity to explore burgeoning sexuality via a fantasy of remote, safe-distance virtual boyfriends."

But that queued up a horrible problem — record execs and so-called "industry intermediaries" leveraged their connection with the stars to get whatever they wanted from young — sometimes, too young — fans. Murray connects that wistful love of the '50s with the Jimmy Page of the 1970s, who had young girls fighting each other for his attention. That's often when other things — like drugs and alcohol — entered into the mix, and suddenly, it wasn't so innocent.

Plenty of those guys were actually into underage girls

"Why," asks The Guardian's Hadley Freeman, "do we turn a blind eye to [Chuck] Berry's convictions, but not Roman Polanski's?" It's an incredibly good question, especially considering the conviction that's being referenced is a two-year jail sentence for crossing state lines with a 14-year old girl, for what was ruled "immoral purposes."

Freeman blames (in part) the industry. Even though Berry was convicted of some downright terrible stuff, other artists continue to sing his praises as well as his songs. And when it comes to underage girls, he's definitely not the only one.

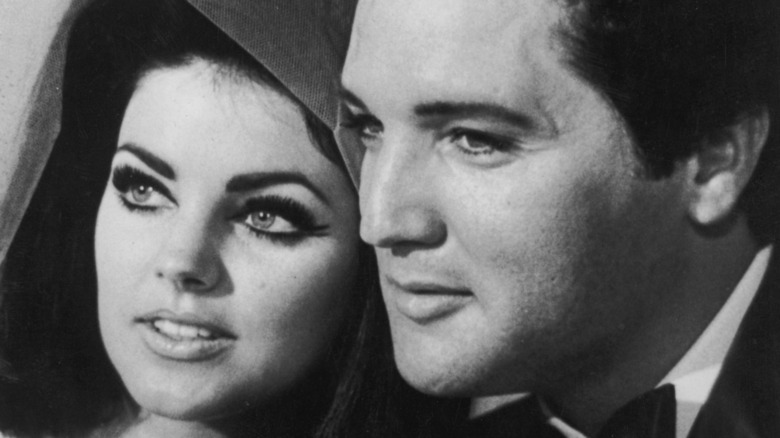

Elvis Presley, reported Vice, had a small entourage of 14-year-old girls who traveled with him when he was on tour, but they weren't the only ones the 22-year-old star liked to "pillow fight, tickle, wrestle, and kiss." His then-girlfriend was 15-year-old Dixie Locke. He didn't meet Priscilla until he was 24 ... and she was 14. After they split in 1972, Elvis rebounded with another 14-year-old.

Then, there's Jerry Lee Lewis. His first tour in England ended in flames when he introduced his wife, Myra — who also happened to be his 13-year-old second cousin, reports The Telegraph. Previously, it was only when Sun Records founder Sam Phillips intervened that Myra's father (and Jerry Lee's bassist), J.W. Brown, decided not to kill the singer. Myra had this to say about the whole thing — "Gee, it's fun being married. The girls at school were mighty envious ..."

Here's how Little Richard's record company ripped him off

Vice says that the music industry is pretty much designed for record executives, and many of today's practices were started in the 1950s.

Little Richard, says Vice, signed his first record contract when he was 19 years old. At the time, he was responsible for his family (his father had been killed three years prior), and he described life this way — "You know you're poor when you have to make a fire and you ain't got no wood. I've seen people pull wood off their houses to make a fire in the house. That's poor. And I was one of the people pulling wood off the house."

He was desperate and only got a contract in the first place after spending a year calling — and begging — one of the only studios who would even consider signing a Black man. Finally they did, and in 1955, "Tutti Frutti" was released — and it was huge. It should have, in theory, made all the family's money worries go away, but it didn't — because while Specialty Records' owner Art Rupe made millions, Little Richard got $50 for the recording and half a penny for every copy. He says he knew it was a bad deal at the time, but if he wanted to make music, he'd had no choice.

DJs got in on it, too

Here's a question — how did songs make it on the radio to become hits? Did DJs pick and choose what they knew their audience was going to tune in to ... or did they play the songs that belonged to the record companies that paid them the most?

The answer is, of course, the latter. According to Performing Songwriter, a huge part of the musical landscape of the 1950s was shaped by payola, which was a practice where record companies would offer DJs money — along with vacations, tons of free stuff, and occasionally even concert proceeds — for playing the songs that the companies wanted them to play. The end result was that record companies could pay their way to hit songs, and it worked so well that by the middle of the decade, BMI (who was all about the payola) had twice the hit singles as the older, larger ASCAP (who protested the whole practice).

It wasn't just a few bucks here and there, either — by the time the whole thing went before the FCC in 1960, DJs were raking in thousands. One Cleveland DJ, History says, made $12,000 between 1958 and 1959 — and for perspective, that's around $110,000 adjusted for inflation. It was seen as an "abuse of public trust," and although technically outlawed, the laws left plenty of loopholes in place that meant it's still practiced today.

American Bandstand had a super rocky start

Dick Clark was the face of American Bandstand, and he's synonymous with the show that brought hits and performers alike right into the homes of fans. When NPR reported on his death in 2012, they noted American Bandstand almost didn't happen.

Before Clark, American Bandstand was hosted by Bob Horn. Horn, says The Cultural Critic, was in his late 30s when the show started in 1952. It was a massive hit, but things started to go sideways when he was arrested for a DUI in June of 1956. Within just a few hours, he'd been fired from his hosting gig. When people started questioning why he'd been dealt with so severely, it started to come out that the local district attorney was in the middle of investigating incidents of "sexual impropriety," and he'd warned the station to get rid of Horn while they could. Within four months, Horn was arrested on "morals charges" after it came out that he had not only been having an affair with a 13-year-old girl, but that he'd also arranged other underrage affairs for the male members of his entourage. Horn was acquitted but was involved in another drunk-driving accident and paralyzed a 5-year-old child.

Needless to say, American Bandstand nearly didn't continue.