The True Story Of The Circulation War Between Hearst And Pulitzer

It's not much of a stretch to say that the press is very powerful. The way the news circulates — and what news circulates — is going to have some sort of sway on public perception. So it sort of makes sense that the press and the way it's used has been a topic of debate over the years.

But there are also some crazy stories about the ups and downs of American journalism through history. And if you wanted to hear about one, well, New York at the end of the 19th century is a good place to go looking. After all, it's pretty much where tabloid journalism first got its start. That, and also those good old clickbait titles you see all over the internet.

It basically circles around a couple of giants in the journalism scene — William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer (yes, as in the Pulitzer Prize) — and the heated competition that raged between them, with the American public sort of caught in the crossfire. Oh, and there's a chance that these two might've, kind of, started an actual, literal war between two countries. Yeah, for real. It's not quite that simple (because, really, when is it?), but it's definitely a very interesting story.

Joseph Pulitzer: soldier-turned-editor

Despite everything that the Pulitzer name would end up meaning over the years, Joseph Pulitzer's story (and the story of the circulation war, by association) started out comparatively humble.

Born in April 1847 in Hungary, Joseph Pulitzer lived a fairly easy childhood, educated in private schools and taught multiple different languages (via Historic Missourians). That said, he wanted to carve his own path, looking to military service and striking out. A lot. Except for with the US military, which was recruiting men to fight in the Civil War. That was in 1864, and so, long story short, he didn't serve for long and found himself working odd jobs to pay the bills before eventually studying law.

Which is all interesting enough, but where do newspapers and journalism factor in? Well, in 1868, he ended up reconnecting with his old commanding officer, Carl Schurz, who also happened to be the part owner of a German language newspaper. Schurz hired Pulitzer as a reporter, where he made a name for himself, rooting out corruption wherever he could find it — bribes, payoffs, the like (via Encyclopedia.com) — and always getting the story first. Within a few years, he'd become a managing editor and part owner himself, only to sell his interest and later return to St. Louis, where he bought The St. Louis Dispatch and grew its reputation for the truth, eventually moving to New York City in 1883 to do the same for his newly-acquired New York World.

William Randolph Hearst: West Coast publishing power

Well, a war has got to have two sides, right? And Pulitzer got his start in the newspaper business a bit earlier, but William Randolph Hearst proved himself as a pretty worthy adversary.

Biography tells us that he was born in San Francisco in April 1863 and grew up surrounded by a decent amount of privilege. His father had moved out to California for the Gold Rush, and, well, he'd done pretty well for himself, becoming a millionaire by the time Hearst was born. (David Nasaw's The Chief explains that things were a bit more complicated and precarious than that, but in a very general sense, the Hearst family was fairly well-off). That money went toward private tutors and lengthy tours of Europe, and eventually, Hearst's education took him to Harvard for a few years, where he managed to make his way into the university's higher social circles. Not that it kept him from getting expelled, though.

But that was really just the beginning. Hearst's father had acquired the failing San Francisco Examiner and managed it without much notable success. Hearst himself had already shown interest in journalism, and he ended up taking it over in 1887. Which was probably the best move for the floundering newspaper. According to History, the younger Hearst invested over $8 million into revamping it with new writers and upgraded equipment; as his star rose on the West Coast, he began to look east, as well.

The state of journalism

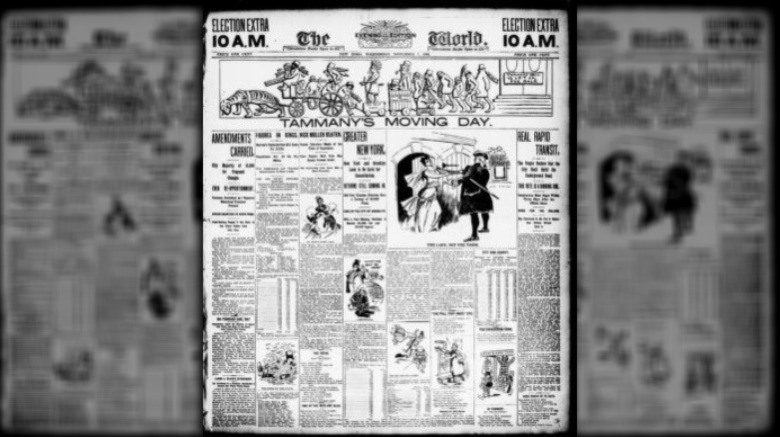

As W. Joseph Campbell explains in The Year that Defined American Journalism, in the late 19th century, the future of the American newspaper was up for debate. Papers like The New York Times favored a detached and impartial treatment of the news. It didn't try to take part in the events it reported on; it just gave facts. (This is ultimately the model that stood the test of time). Other papers were more like literary journals — stories about the ups and downs of life in New York, not reports on current events. But regardless of the exact content, the news didn't look appealing: bland text and narrow columns, up to 30 stories all packed onto the front page with no pictures (via History).

Hearst and Pulitzer set out to change that. Pulitzer changed newspapers from a way to get dry information into a source of entertainment, as ThoughtCo puts it. He wrote for the general public, supporting unions and including investigative journalism as a way to expose corruption, all while adding colorful pictures, comics, and big headlines to grab the eye (via Communication in The Americas and their Influence). Basically, it was really flashy. Hearst drew inspiration from Pulitzer and used the same sorts of tactics, and added to that, seeing the newspaper as a force of good in people's lives. It shouldn't just report but try to actively right the wrongs that the public faced, especially in cases where the government wasn't doing that.

Hearst really admired Pulitzer

So, yes, these two did pretty much get into a war over American journalism, but their relationship with each other wasn't exactly one of instant hate. At least, that was the case on one side.

See, while Hearst was still at university, he managed to become the business manager of The Harvard Lampoon. As David Nasaw's The Chief puts it, this was his first real taste of publishing, and he did a really good job at it. Before he began running things, the magazine was pretty much about to go under, but under his watch, the magazine actually started to turn a profit, and its circulation exploded.

Around the same time, his father had acquired The Evening Examiner (later the San Francisco Examiner), and Hearst was the perfect person to take it over. To prepare for the job, he basically took Pulitzer's paper The New York World as his textbook, reading it regularly and examining everything it did. In letters to his father, he named The World one of the best papers, and one which The Examiner should be able to compete with, mentioning its "startling originality" as something that they should be striving for. They would do well to hire the same kinds of youthful and intelligent people that The World did (Hearst actually recommended hiring one of The World's editors in a different letter), and he sent his father copies of The World, just as an example of what The Examiner should be doing.

Competition between Hearst and Pulitzer

Finding a lot of success with The San Francisco Examiner, Hearst turned his eyes and ambitions east. When he bought The New York Morning Journal, Pulitzer suddenly had some pretty threatening competition. Hearst started an evening version of the Journal, while keeping up with all the tactics Pulitzer himself had pioneered (via Biography) — big headlines, colorful stories, and pictures. And on top of that, Hearst cut the price of his papers down to just one cent: even more motivation for any random passersby to pick up the Journal as opposed to the World. Of course, Pulitzer matched that price; he had to stay competitive.

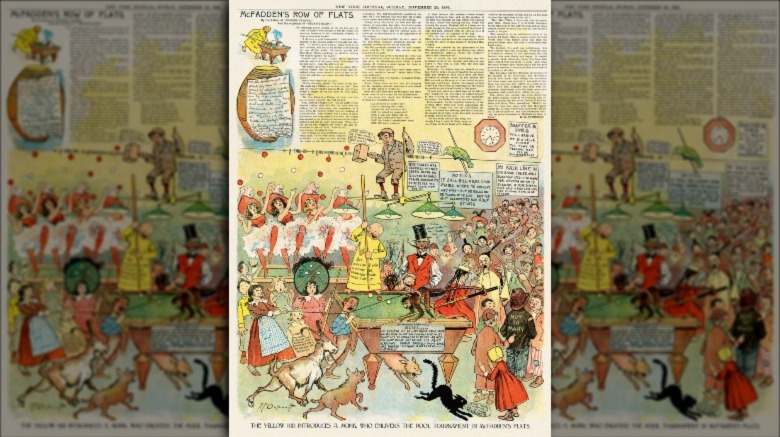

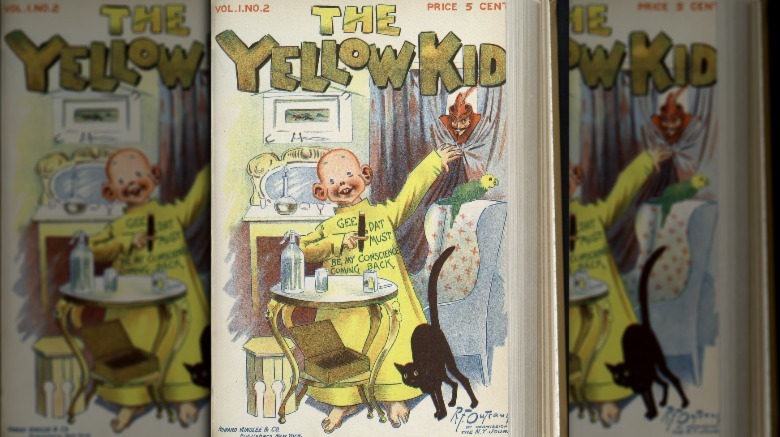

But it wasn't just the audience. Upon starting up his tenure at the Journal, Hearst started hiring away Pulitzer's employees, offering them higher salaries; one of those employees was Richard F. Outcault. According to the Office of the Historian, Outcault wasn't a nobody, but the artist of the popular comic strip Hogan's Alley, which depicted life in the New York slums, with its most famous character, The Yellow Kid (which is potentially the origin of the term "yellow journalism"). The comic strip and character originated in the World, but Hearst wanted it for the Journal. So of course, he tried to tempt Outcault away, and Pulitzer was not pleased. A bidding war started up for the comic and its artist, with Hearst eventually coming out on top (although Pulitzer ended up hiring a new artist to keep drawing the comic anyway).

What's yellow journalism?

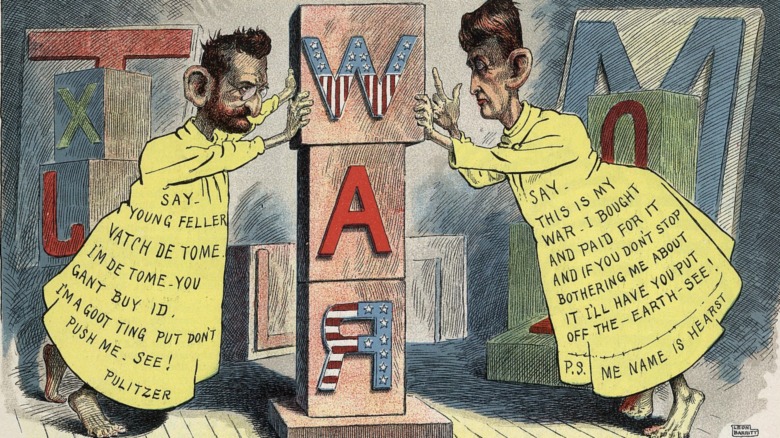

At the end of the day, the circulation war between Hearst and Pulitzer — this competition for dominance in the New York journalism scene — really had one especially big thing come out of it. The term "yellow journalism."

Alright, but what's yellow journalism anyway? As ThoughtCo puts it, yellow journalism is basically a form of reporting that's incredibly sensationalist, intending only to pull readers in with salacious stories and provocative headlines. History adds that big, bold headlines and fun illustrations were also indicative of yellow journalism, and, hey, that sounds familiar, doesn't it?

Yeah, it's the exact thing that Hearst and Pulitzer were doing to sell their papers, but the moral of this story isn't that they'd created something new and great, exactly. Sure, it had its benefits — their headlines were basically the 19th century version of clickbait, which did generate some pretty good traffic for both of them — but it's also not wrong to say that yellow journalism was as reckless as it was interesting. After all, this was the news, not a random viral video; people were looking to them for facts and truth. Embellishing the facts was something other reporters at the time were criticizing, and for good reason. It could (and did) have some pretty major consequences as the 19th century came to an eventful close.

The explosion of the USS Maine

Throughout the 19th century, tensions were on the rise. Not between the US and another country, but between Spain and Cuba as the latter fought for independence. As Encyclopedia.com explains, those tensions were built on Spanish imperialism and oppression, then grew due to changing norms (things like industrialization, the US Civil War, and failed legislation). Throughout all that, the US pretty much just watched from the sidelines.

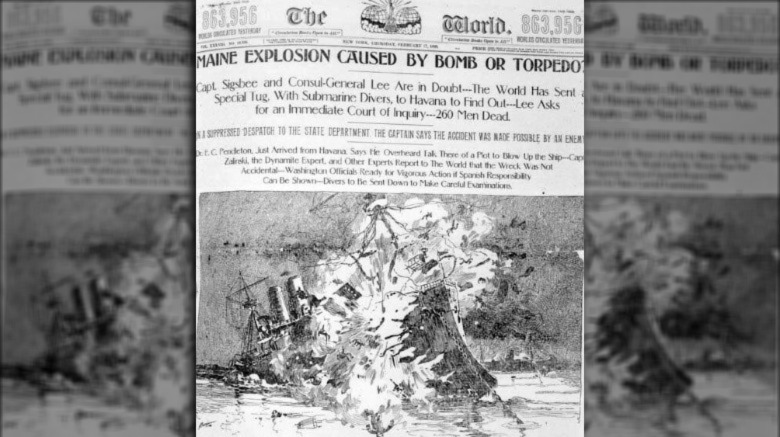

Things didn't stay that way, though. On February 15, 1898, an explosion shattered that status quo: the battleship called the USS Maine suddenly blew up while in Havana Harbor (via History). It'd been there on a friendly visit, basically just patrolling, but all of a sudden, about 260 American crew members were killed in the blast.

Word got out, and some really colorful rumors started to fly. Investigations conducted decades later painted a story that, really, wasn't all that interesting in the end. Most likely, it was an accidental explosion — a fire that lit the ammunition on board. A tragic accident, but specifically an accident. This probably wasn't sabotage, no Spanish mines set in the harbor, nothing premeditated. At the time, no one could really say what exactly caused the explosion, but in the heat of the moment, that uncertainty didn't really matter. People thought they knew what happened, rallying around the cry "Remember the Maine, to hell with Spain!" (via U.S. History), and that was, in part, due to Hearst and Pulitzer.

Coverage of the USS Maine explosion

Whatever the exact reason for the explosion of the USS Maine, it was an explosion of an American battleship in Cuba, in the midst of a Cuban rebellion against Spain. And that was the perfect sort of headline.

Already filled with stories of brutality against Cuban rebels, their papers were suddenly filled with juicy accusations (via U.S. History). "Invasion!," "Spanish Treachery," and other really similar headlines flooded out, pointing the finger at Spain for the tragedy (via History). Entire front pages were dedicated to the explosion, the page filled with huge pictures, or offers of thousands of dollars as a reward for anyone who could find the perpetrator of the explosion. All of a sudden, in the words of Hearst and Pulitzer, the explosion was the start of a national crisis with some Spanish mastermind at the center of it.

They just really, really wanted to outdo each other, and what better way than to have the juiciest, most scandalous rumors on the front page? People would absolutely pick up the paper if it promised a tale of evil and sabotage and deceit, and each of them wanted to be the paper with the best tales. But that was really the problem. People did start to believe them and their stories of Spanish villainy, even though all they were printing was propaganda. According to The Public Domain Review, what they were printing was unsubstantiated claims at best. Or complete lies and errors at worst.

Did Hearst and Pulitzer actually start the Spanish-American War?

Newspapers starting a war sounds a little ridiculous, maybe there's something to it. Some sources, like ThoughtCo, will actually name these two and their papers as potential influences for the conflict — they stoked the fires of public opinion so strongly that the US government had to declare war. Hearst in particular did seem to be pretty active in the entire situation in Cuba — he and the Journal had actually organized the jailbreak of a political prisoner in Havana (via The Year that Defined American Journalism), and he's supposedly responded to an artist's update on the lack of fighting with an ominous quote: "You furnish the pictures and I'll furnish the war" (via Communication in The Americas and their Influence).

But, really, as easy as it is to place the blame on the newspapers, the reality might not be that straightforward. There's no evidence of Hearst's quote being real, and History explains that most academics don't actually accept this idea anyway. There had already been tensions between Cuba and Spain that existed regardless of the American press, and all Hearst and Pulitzer did was draw some extra attention to it. And besides, there's no proof that the US government would actually look to the newspapers to seriously come up with foreign policy; the declaration of war more likely stemmed from a desire to show American power and expand overseas that had already been present for well over a decade (via Office of the Historian).

The aftermath of the wars

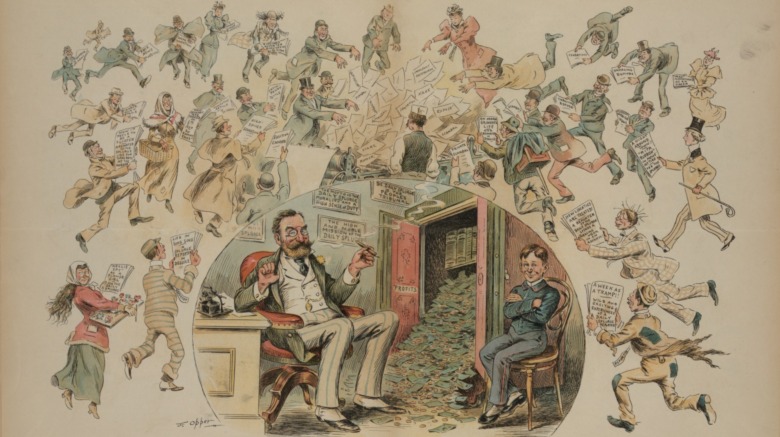

When it comes to the Spanish-American War, after a handful of months, Cuba won its independence, and the US took over some of Spain's colonies (via Encyclopedia.com). Pretty simple. But back in New York, the circulation war brought bad press. Political cartoons available on The Public Domain Review paint Hearst and Pulitzer (but mostly Hearst) as war-mongering snakes, battling it out to try and poison the public, filling their papers with complete lies and unsubstantiated attacks. One of those cartoons equated Hearst to Lucrezia Borgia which is... not the best look.

Their contemporaries called their journalism a form of evil in and of itself, and one that was so prevalent, it almost seemed like the people just wanted vulgarity. There's a point there, though it wasn't exactly the case. As ThoughtCo says, in the aftermath of the war, the public actually began to distrust the news in general; that's what made editors realize how important credibility really was, setting up the future of journalism.

Pulitzer himself actually came to realize this, too. His motto had been "Accuracy! Terseness! Accuracy!" and, seeing how yellow journalism had corrupted his papers, returned to his roots after a couple years (via Historic Missourians). And that worked out well; his name is associated with one of the top honors for journalism. As for Hearst, things shortly began to fall apart. According to History, he stopped innovating and fell behind his competition, his journalistic empire crumbling in the decades that followed.