Things You Didn't Know About Serial Killer Belle Gunness

One might call Belle Gunness a "black widow killer." She was a Norwegian-born serial killer thought to have murdered at least 14 people and perhaps as many as 40 in the late 1800s and early 1900s throughout Illinois and Indiana. While it's true that she did apparently kill two of her husbands, she wasn't content just to off her spouses. It's believed that Gunness also killed her own children, a baby stepdaughter, her adopted daughter, and many men she tricked into coming to visit her via personal ads in lonelyhearts columns.

Per Biography, Gunness was born Brynhild Paulsdatter Strseth on November 11,1859 in Selbu, Norway. She immigrated to the United States in 1881, apparently "searching for wealth," and married her first husband, Mads Albert Sorenson, in Chicago, Illinois, in 1884. Shortly after the wedding, the couple's candy store and home burned down, and they filed and collected an insurance claim. Sorenson soon died of heart failure "on the one day his two life insurance policies overlapped." According to the New York Post, Belle reported that he had come home with a headache. She'd given him quinine powder and made dinner; when she returned to check on him, he was dead. His family requested an inquiry into his death, but it didn't come to be. Two of the couple's children died in infancy; Biography suggests Gunness may have poisoned her own children to collect insurance money.

Another dead husband

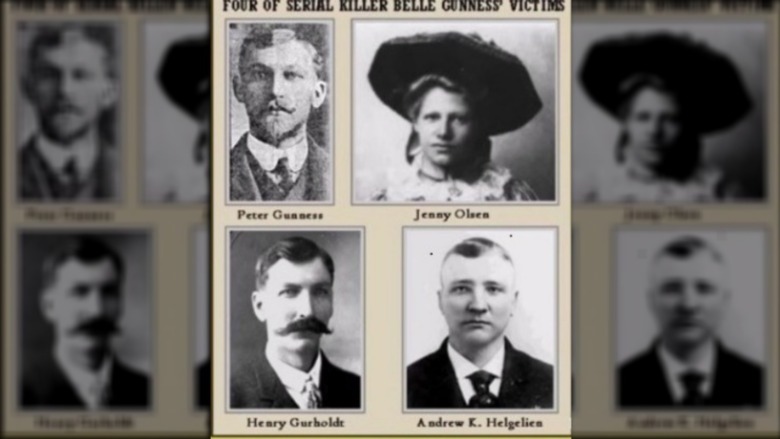

As reported by Mental Floss, Belle used the money from Sorenson's insurance payout to buy a farm in La Porte, Indiana. She soon married her second husband, widower Peter Gunness. Within a week of their marriage, Gunness' 7-month-old infant daughter died and a few months later, Peter Gunness died "in a freak accident after a sausage grinder fell from a high shelf and struck his head." The coroner was suspicious enough to investigate his death, but nothing came from it.

In 1905, Belle Gunness began placing personal ads in Norwegian-language newspapers; Mental Floss quotes one: "Personal — comely widow who owns a large farm in one of the finest districts in La Porte County, Indiana, desires to make the acquaintance of a gentleman equally well provided, with view of joining fortunes. No replies by letter considered unless sender is willing to follow answer with personal visit. Triflers need not apply." Her ads were effective; Gunness reportedly received up to eight replies per day.

Gunness had a long list of victims

Per true crime author Harold Schechter, interviewed by the New York Post, Belle Gunness "was very shrewd in identifying potential victims. These were lonely Norwegian bachelors, many completely cut off from their families. She beguiled them with promises of down-home Norwegian cooking and painted a very seductive portrait of the kind of life they'd enjoy." She exchanged letters with a man named Andrew Helgelien for 18 months. It started out as a possible business partnership, but it turned romantic, with Gunness sending letters with lines like "I place you higher in my affections than anyone on this earth."

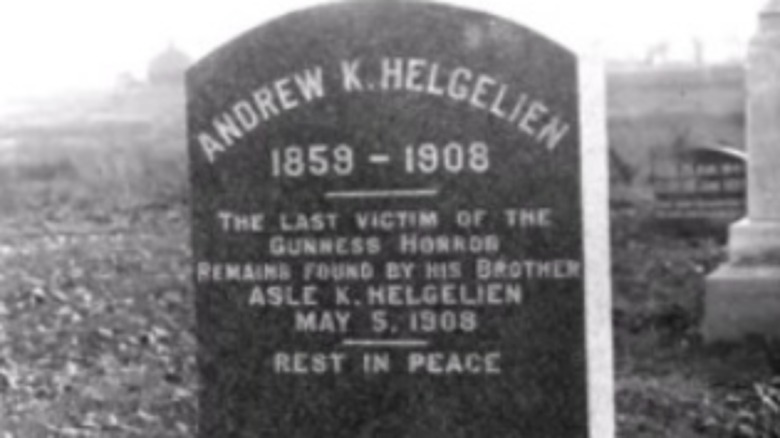

Helgelien arrived at her farm on January 3, 1908; they soon went to a local bank where he deposited CDs totaling $2,839 (the modern equivalent of about $75,000). When the money was available, the couple returned and Gunness demanded it in cash. It was the last time anyone else saw Helgelien alive. Other men who answered Gunness' personal ads and came to her farm with money included George Berry ($1,500), Christian Hilkven ($2,000), Emil Tell ($2,000), Ole Budsberg ($1,000), and John Moe ($1,000). All of them disappeared.

What was Ray Lamphere's role?

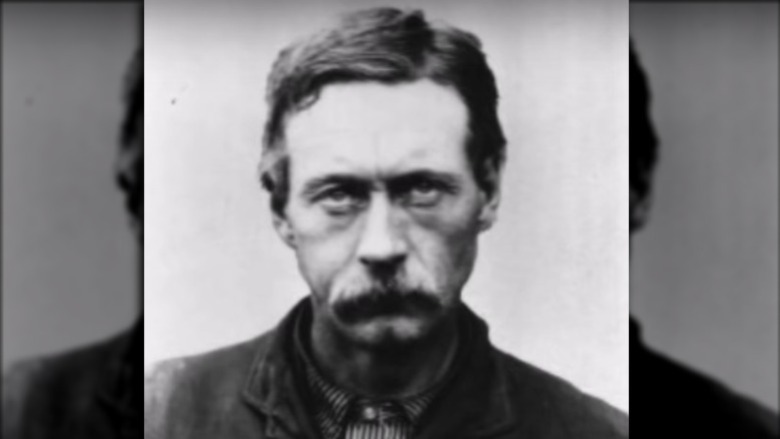

While Belle Gunness was exchanging letters with Andrew Helgelien, she hired a man named Ray Lamphere (above) in July of 1907 as a farmhand. The two became lovers, per Mental Floss, but he was too poor for Gunness to seriously consider him as a potential partner. When Helgelien arrived on the farm, Gunness unceremoniously kicked Lamphere out of his room and told him to sleep in the barn, much to his displeasure. A few weeks later the two got into an argument and Gunness fired Lamphere. He reportedly began harrassing Gunness and she wrote letters to the local sherriff complaining about his behavior, accused him of tresspassing on her property, and even tried to have him declared mentally insane.

Soon after these events, Andrew Helgelien's brother Asle became worried after hearing nothing from his brother. He found the letters Andrew had received from Belle telling him "Take all your money out of the bank and come as soon as possible." Asle wrote to Gunness asking of Andrew's wearabouts, and she replied that his brother had left for Chicago and sent her a letter telling him not to contact him, making Asle even more suspicious.

The Gunness farm burned to the ground

On April 27, 1909, Belle Gunness went to see her lawyer to draw up her will, as reported by Mental Floss. She shared that Lamphere's behavior was making her nervous and declared, "I want to prepare for an eventuality. I'm afraid that fool Lamphere is going to kill me and burn my house."

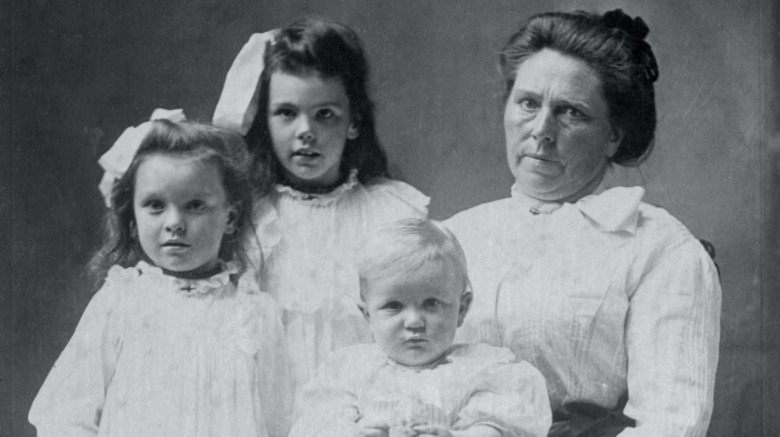

Per the New York Post, Gunness' farmhouse burned down on April 28, 1909. Three of her children burned to death and it was presumed that Gunness had died as well, since a women's body was found in the remains of the property (pictured above). Her death couldn't be verified, however, because the body found in the ruins was missing a head. Lamphere was arrested and charged with murder and arson. People from the town arrived at the farm to search for the missing head. Among them was Asle Helgelien, who had heard about the fire and come from South Dakota looking for his brother.

The head was never found, but as people searched the property, they started finding other body parts. On May 3, they found a severed human arm that turned out to belong to Andrew Helgelien. Further digging turned up "a jumble of putrified body parts: naked torsos wrapped in burlap, heads, arms and legs scattered around," including the remains to Gunness' adopted daughter Jenny Olsen. Gunness had told people Olsen had gone away to school in California.

The Mistress of the Castle of Death

Within days, the story of Belle Gunness and her body count spread, and newspapers came up with a series of catchy nicknames, including "the Indiana Ogress," "the La Porte Ghoul," "the Mistress of the Castle of Death" and "Hell's Princess," per the New York Post. Police kept digging (literally), finding bags of body parts in the ground, according to Mental Floss. They stopped counting after 11.

The farm became a tourist attraction, with curious crowds of up to 20,000 people gathering in La Porte "to watch body parts yanked from the dirt." Police also realized that if the headless woman wasn't Belle Gunness, she was now at large. Sightings of the missing murderess poured in from around the country, but on May 19, authorities searching the property found a pair of dental bridges in the rubble, and a dentist identified them as having belonged to Gunness. Authorities considered the case closed, but many people suspected she had escaped and was running free.

Lamphere escaped murder charges, but was still charged with arson, although many believed Gunness was the one who set the fire. He spent a year in prison before dying of tuberculosis.