Secrets Marvel Doesn't Want You To Know

For generations, Marvel Comics has captured the world's imagination with a seemingly endless parade of superheroes. These fantastical, fleshed-out characters live in the pages of comics, on TV shows, in huge blockbuster movies, and in the world at large — Marvel characters like Spider-Man, Iron Man, Captain America, Black Panther, and the X-Men are cultural touchstones, literary figures, and modern mythological icons all at once.

Providing millions with extremely entertaining content has made Marvel a powerful company, and a very wealthy one. Now owned by Disney, Marvel's influence and bank account grows every time they put out another entry in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, or a superhero TV show, or a new toy line. So while Marvel may be in the business of making magic, Marvel is still a business, and the rules of that world apply. People can get greedy and litigious if it means keeping the company afloat and the bottom line intact ... or they can just make really bad decisions. Here are some of the less than savory shenanigans that have embroiled Marvel over the years.

The strange origins of Doctor Strange

Doctor Strange wasn't the typical entry in the Marvel Cinematic Universe. After getting audiences used to hammer-wielding Thor and and flying metal guy Iron Man fighting big strong bad guys, this one found Benedict Cumberbatch as a doctor traveling through the mystical mists of time and space with an irascible cape. Doctor Strange was, well, strange, but what Marvel Studios put up on screen is certainly preferable to what they could've done, and cinematically re-created the comic's early days from the 1960s. They haven't aged well, what with the stereotyping and racism.

From the beginning, the character of Doctor Strange was a mystic, which, to Marvel, and in those days, meant he had to hail from Asia. He looked like, and was inspired by, certain Asian stereotypes. The character first only appeared in small, occasional stories, but when readers wrote in asking to see more Doctor Strange, Marvel obliged and made him the star of his own series. And that's when they turned him into a Caucasian character, which is problematic in its own way. This makes the conversation about cultural appropriation that surrounded the release of the Doctor Strange film in 2016 feel terribly ironic.

Trouble in the Marvel romance department

Believe it or not, there was a time when Marvel didn't just put out comics about big muscleheads beating up other big muscleheads. Between the mid-1940s and late 1970s, Marvel published "romance" comics, stories about couples falling in and out of love, and reading very much like a combination of cheesy Harlequin-type novels and daytime soap operas. From a modern perspective, these melodramatic tales full of purple prose are corny and dated, and yet in 2003, Marvel decided to revive the forgotten genre with a miniseries called Trouble. So then who did Marvel hire to bring back romance, perhaps an established writer of romance novels? No, they got comics writer Mark Millar to do it. He's best known for stuff like Judge Dredd, Swamp Thing, and Kick-Ass. You know, real lovey-dovey stuff.

And the trouble with Trouble didn't stop. The plot pulls from the Marvel superhero world, presenting a scenario in which characters implied to be teenage versions of Peter Parker's Aunt May and Uncle Ben hit the Hamptons, and long story short, there's an unplanned teenage pregnancy and Aunt May is Peter's secret birth mother. Perhaps even stranger is the inexplicable and a little creepy cover of the first issue of Trouble: a photograph of two very young girls in bikinis. Needless to say, Trouble did not revive romance comics.

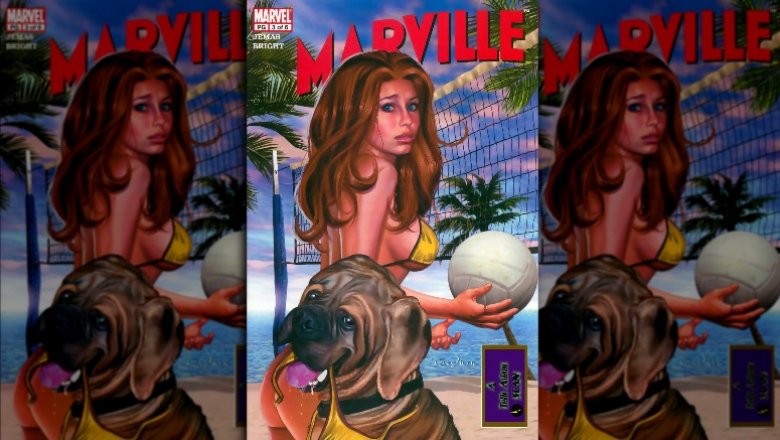

The Captain's Marville

Marvel entertainments are both popular and populist, which makes the 2002 miniseries Marville all the more baffling. It's an extremely self-indulgent title, full of esoteric references to the comics business and ham-fisted jokes about media conglomerates run amok. That's deliciously ironic, considering that Marville was written by Marvel executive Bill Jemas. The plot is somehow even more cringe-inducing. Set in the year 5002 on an Earth owned by AOL (who bought it from Ted Turner), a hero named KalAOL is sent back in time to the year 2002 to save the world from deadly meteors. Your average reader wouldn't know any of that from a Marville cover, which usually featured a drawing of a provocatively posed, semi-nude woman ... which had nothing to do with the story.

This was a comic obviously both by and for Jemas, who smugly admitted as much in a Marville bind-up. "Marville does not have the stuff that makes for top-selling comics, but it does explore the origin and meaning of life, so I thought it was worth a six-issue series," he wrote. "And, because I'm president of Marvel, I could ignore the bean counters and publish Marville without regard for minimum sales projections and margin requirements."

Marville disappeared from comic shops, but not the angry hearts of comic book experts. It frequently ranks on lists of the worst comics of all time.

Marvel toys make the money

Spider-Man is one of the most recognizable, widely liked, and popular superheroes in the world ... and that's not even taking comic book sales or box office revenues into consideration. Sure, Spider-Man: Far from Home took in $1.1 billion worldwide in 2019, but that's nothing compared to the cash Marvel brings in from Spider-Man merchandise. In 2013 alone, about $1.3 billion worth of Spidey stuff soared off shelves — toys, blankets, shoes, backpacks, and the like. That's more money than Avengers, Batman, and Superman merchandise sold in that same time frame combined.

Spider-Man is a golden goose, and it's definitely one of the reasons why Disney fought so hard with rival studio Sony to keep Spider-Man in the Marvel Cinematic Universe. The House of Mouse owns the merchandising rights to the webslinger, and every time he appears in an MCU movie, it's not just cinematic magic, it's also a commercial for more Spider-Man stuff.

The Marvel war for War Machine

Ta-Nehesi Coates is a remarkable writer, probably best known for Between the World and Me, his book about life as an African-American man. That won Coates the National Book Award for Nonfiction in 2015, the same year he landed a Genius Grant from the MacArthur Foundation. And while comics are traditionally considered "low art," this literary marvel joined Marvel to write a Black Panther series. The first issue sold more than a quarter of a million copies, easily making it the bestselling comic of April 2016.

Later that year, Marvel trotted out event miniseries Civil War II. The publisher wanted to start it off with a high-stakes death, one that would deeply upset main characters Carol Danvers and Tony Stark. The plan: kill off James "Rhodey" Rhodes, a.k.a. War Machine, and also Tony's best friend and Carol's boyfriend.

War Machine is among the very few African-American characters in the Marvel canon, and Coates thought that losing one of those precious few would be a step in the wrong direction. Coates fired off a pointed letter to Marvel executive editor Tom Breevoort and editor-in-chief Axel Alonso. "I feel like we stand on decent ground saying if there had to be a death, it should be Rhodey because of his relationship with the characters, not because of the color of his skin or his lack of prominence in the Marvel Universe," Breevort told Newsarama. And then, ignoring one of the most celebrated writers of his generation, Marvel went ahead and killed off Rhodey.

Marvel vs. the guy who helped make Marvel what it is

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Jack Kirby and Stan Lee together created some of the biggest names in comics, including Iron Man, the Fantastic Four, and Captain America. Lee's work is common knowledge, but that's not so much the case for Kirby. And it's all because of contracts. When the pair came up with those properties, Lee was a Marvel employee, but Kirby was a freelancer. That meant he didn't have any rights to all those remarkable — and profitable — creations.

In 2009, 15 years after Jack Kirby's death, his four adult children sent more than 40 termination notices to Marvel, Disney, Fox, Universal, Paramount, and Sony, ordering them to stop developing projects based on more than 260 works created by Jack Kirby. The aim: reclaim ownership of the copyrights of their father's characters. The following year, Marvel filed a claim of its own, asking a court to invalidate the Kirbys' strike. Marvel didn't deny Kirby's contributions, just that he had any rights to them. "Everything about Kirby's relationship with Marvel shows that his contributions were works made for hire and that all the copyright interests in them belong to Marvel," company lawyer John Turitzin said in a statement. Courts ruled in Marvel's favor, prompting the Kirbys to ask the Supreme Court to review the case. Just before the highest court in the land was set to weigh in, the Kirby family and Marvel reached an out-of-court settlement, the terms of which were not made public.

Giving up the Ghost

It was a freelance comics writer named Gary Friedrich working for Marvel in the early 1970s who introduced Ghost Rider to the superhero canon. The bike-riding, flaming-headed character first appeared in an origin story in 1972's Marvel Spotlight #5. Flash forward to 2007, when Friedrich, Ghost Rider's credited creator, sued Marvel, Sony Pictures, Hasbro, and a lot of other companies involved with Ghost Rider adaptations (including the 2007 Nicolas Cage Ghost Rider film) and merchandise, alleging a "joint venture and conspiracy to exploit, profit from, and utilize" the Ghost Rider character without his approval. Friedrich claimed that when it contracted him to make Ghost Rider books in 1971, Marvel (at the time, Magazine Management) neglected to properly file copyrights on the character, meaning the rights reverted back to him in 2001. A U.S. District judge ruled in Marvel's favor in 2011, attesting that Friedrich signed over all rights to Ghost Rider in 1971 and again in 1978, when he thought it meant Marvel would give him more freelance opportunities. Two years later, an appellate court overturned the decision and Marvel and Friedrich quietly agreed to an undisclosed, out-of-court settlement.

The X-Men's origins from a place of Doom

Artistic inspiration can come from anywhere — real life, a movie, a dream — or an artist, writer, or multinational corporation can swipe an idea from their arch-rival and change it just enough to not get sued for copyright infringement. Marvel Comics' long, storied history is marked with lots of stories and characters that look a lot like DC Comics properties.

In June 1963, DC debuted the Doom Patrol, a group of misfits who team up to fight the good fight under the tutelage of a mastermind who requires the use of a wheelchair. Cut to four months later with the first issue of X-Men, a comic about a group of misfits who team up to fight the good fight under the tutelage of a mastermind who requires the use of a wheelchair. In 1964, the Doom Patrol fought the Brotherhood of Evil, while the X-Men went to war against the totally different Brotherhood of Evil Mutants.

"Over the years I've became more and more convinced that [Lee] knowingly stole the X-Men from the Doom Patrol," Doom Patrol creator Arnold Drake told Newsarama. "An awful lot of writers and artists were working surreptitiously between" Marvel and DC, and "it would've been easy for someone to walk over and hear that this guy Drake is working on a story about a bunch of reluctant superheroes who are led by a man in a wheelchair."

Marvel's not-so-secret messages

Indonesian artist Ardian Syaf drew for the April 2017 title X-Men Gold #1, and amidst all the mutants and mayhem, he subtly included the messages "QS 5:51" and "212." The former is a verse from the Koran, the holy text of the Islam religion. That verse has been interpreted as a warning to not trust non-Muslims. The 212 is an abbreviation of 12/2 or December 2, the date of a protest march in 2016 against Jakarta, Indonesia governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, a Christian, after the politician made some misleadingly negative statements about Islam. (Another Syaf panel isn't so subtle — the letters "J-E-W" can be seen on a wall behind Jewish character Kitty Pryde.) Syaf's additions were quickly discovered and led to a firestorm on social media. Marvel released a statement (via Polygon) that read, in part: "The mentioned artwork in X-Men Gold #1 was inserted without knowledge behind its reported meanings. These implied references do not reflect the views of the writer, editors, or anyone else at Marvel and are in direct opposition of the inclusiveness of Marvel Comics and what the X-Men have stood for since their creation." The publisher promised to remove the imagery from all future printings, and quickly fired Syaf.

Syaf issued an apology and explanation. "My career is over now," he wrote. "It's the consequence of what I did, and I take it."

Don't say it!

In 1979, Marvel and D.C. filed a claim with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office over joint, mutual ownership of the word "superhero." While this is a very common word to describe a set of traits throughout fiction, the federal government agreed with the publishers' claim that when people think of superheroes, they think of the superheroes of movies and comic books, the majority of which are the intellectual property of Marvel and DC. The trademark became official in the early '80s, and it means that no other company can publish comic books or release a wide variety of merchandise and use the word "superhero" in its name.

That means the two biggest names in superhero comics gave themselves a duopoly on the genre, and legally at that. It's a right that the companies tenaciously fight. In the early part of the 2000s, one or both companies prevented more than 30 different entities from using the word "superhero."