The Bizarre True Story Of The Somerton Man

The Somerton Man case is unsolved, and there is compelling evidence to suggest that someone wants it to remain that way for reasons that are not clear. The case involves not only an unknown poison, a book of Farsi poetry, and an unidentifiable corpse but also ballet and a even professor fixated on the number of teeth a person has. Internet sleuths also tie in a baby's death, perhaps killed to shut up his parents, and the brother of a politician who died in a hauntingly similar manner. Eerily, some names and details echo in unrelated cases.

According to the Government of South Australia Attorney-General's Department, the inquest into the death of the man — opened from June 17 to 21, 1949 — was adjourned sine die ("without means"). The case was never closed, and it does not seem that it ever will be.

Someone, it seems, was not too bothered by the man being found but would not allow him to be known.

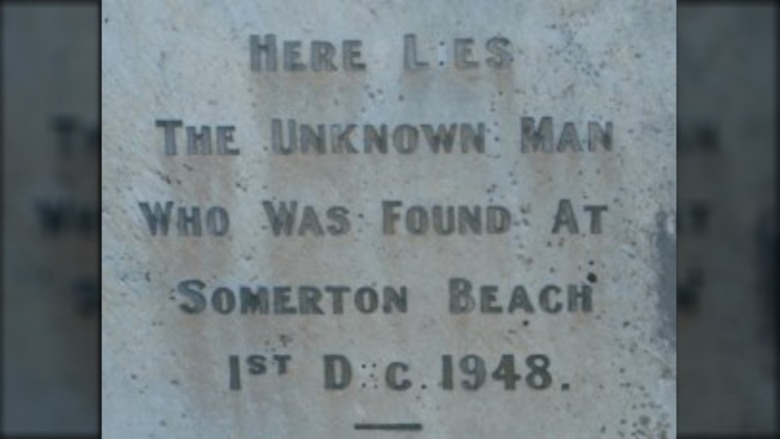

The Somerton Man was found on a beach

On December 1, 1948, a man was found dead on Somerton Beach in Adelaide, Australia. The Government of South Australia Attorney-General's Department notes that several witnesses saw him on the beach the day before "sleeping," and they thought he was drunk, according to Phys.org. John Bain Lyons and his wife saw the man from about 20 yards away that evening. According to Smithsonian Magazine, he tried and failed to raise his arm. This may well be the last time anyone saw him alive. In 1959, investigator Garry Feltus happened upon a police report stating that a witness "saw a man carrying another on his shoulder, near the water's edge."

According to News.com.au, two trainee jockeys exercising their horses discovered the body, an unsmoked cigarette on his chest. When they looked through his pockets, they found mundane items but nothing that would indicate who this man was. All the tags had been cut out of his clothing. The body reached the Royal Adelaide Hospital three hours later. At that point, Dr. John Barkley Bennett had pronounced his time of death as no earlier than 2 am. The people who'd passed him on the beach could have possibly saved him and prevented this mystery.

There were no outward signs of trauma that would explain why a man who otherwise looked like a healthy, even athletic, 40-year-old would have fallen dead.

The autopsy

According to the Government of South Australia Attorney-General's Department, although other files related to the case are still locked away, the coroner's inquest files have been released.

While, in some ways — such as his high calves that implied he may have done ballet — he was the picture of health, Phys.org states his spleen "was strikingly large and firm, about three times normal size," and his liver was distended with blood, according to Smithsonian Magazine. (His last meal had likely been a pasty. Death had occurred before digestion, but it was not poisoned.)

Deputy Government Analyst R.J. Cowan did not know "of poisons which can cause death but decompose in the body so that they are not discernible on analysis" and stated that "if death were caused by any common poison, my examination would have revealed its nature." The Northern Star reports that pathology professor John Burton Cleland felt the poison must be "something that kills in a few hours and does not cause convulsions or a struggle." In open court, Sir Cedric Stanton Hicks would not name the two poisons he suspected. Instead, he passed Cleland a note that the candidates were digitalis and strophanthin.

The Somerton Man had two genetic quirks. His upper ear hollow was more prominent than his lower, and Phys.org notes that he was missing both his lateral incisors. Those alone should have been a significant clue to finding out who he was.

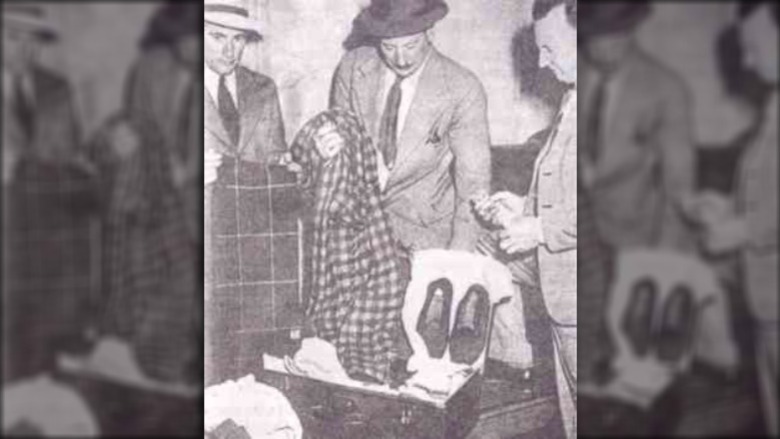

The Somerton Man's clothes and suitcase

A ticket from Adelaide to Henley Beach dated the day before was found in the man's clothing. According to the Government of South Australia Attorney-General's Department, no ticket seller or bus conductor remembered him, but they can't be expected to when questioned months after the death.

This lead eventually brought the investigators to a brown suitcase at the bus station, abandoned on November 30. The contents identified the man as "Kean" or "T. Keane," according to The Northern Star. A quick search of missing persons showed that no one by that name. According to Smithsonian Magazine, the police suspected that someone "had purposely left them on, knowing that the dead man's name was not 'Kean' or 'Keane.'"

In the suitcase was orange thread that had been used to repair the man's pants. The container otherwise had no stickers or markings that would allow them to discern the owner's identity. While more modern methods could pull more information from the suitcase, the government of Australia destroyed the evidence in 1986, saying that it was "no longer required."

Later, when going through the Somerton Man's clothing, Professor Cleland found a slip of ripped paper in his watch fob pocket reading "Tamám shud."

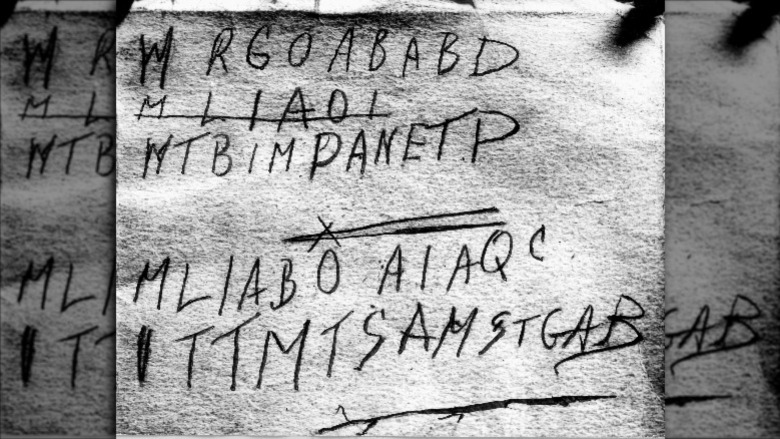

The Somerton Man code

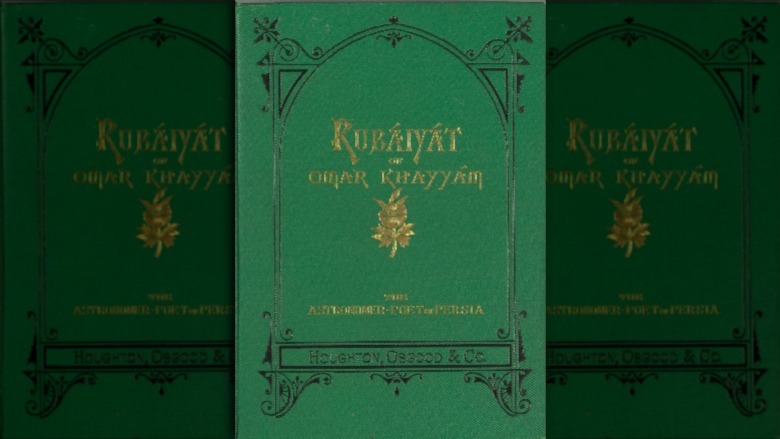

According to the Government of South Australia Attorney-General's Department, the words "Tamám shud" had been torn from the last page of a rare copy of Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám. They meant "The end" or "to finish" in Farsi. For those who believed that the case of the Somerton Man was a suicide, this was as good as a note. Detective Raymond Leane disagreed: "There is no fact that I know of which points towards suicide and abolishes the possibility of murder."

Then the book appeared, a day after the inquest was adjourned, on June 22, 1949. A man told the police that the book had been tossed into his car's back seat on November 30, 1948, parked close to where the body would be found. His brother-in-law presumed it belonged to the man, while he assumed it was his brother-in-law's. According to Smithsonian Magazine, it ended up in the glove compartment until he realized that it might be what police were seeking.

In the back was the hole that fit the paper and, News.com.au reports, indentations. Police used ultraviolet light to find an unlisted phone number as well as a coded message, pictured above.

Accord to Phys.org, in recent years, Professor Derek Abbott has tried to crack the code from sometimes unusual angles, including getting his students drunk and having them write random letters. These experiments have indicated that the letters in the book have a structure and likely mean something. The best guess is that the letters were a "one-time pad code" and might not ever be decoded.

Jestyn

The phone number led police to a home 400 meters from where the Somerton Man was found, according to News.com.au.

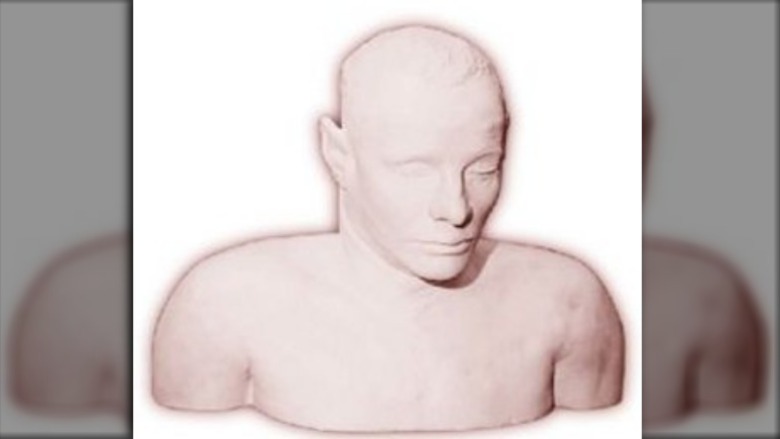

The woman who lived there, Jessica Thomson, aka "Jestyn," claimed that she didn't know the mystery man. Detective Leane showed her a plaster cast of the Somerton Man and reported, according to Smithsonian Magazine, that she was "completely taken aback, to the point of giving the appearance she was about to faint." When asked about the book, she said that, in 1944, she had given a copy to a man named Alfred Boxall, according to Unfreezing Cold Cases, whom the police assumed must be the Somerton Man. This was complicated by the fact that Boxall was still alive, and his copy was intact.

Thomson died in 2007 and cannot give us any more answers, though she never seemed inclined to. The Advertiser quoted Thomson's daughter Kate as saying, "She had a dark side, a very strong dark side. She said to me she, she knew who he was, but she wasn't going to let that out of the bag so to speak. There's always that fear that I've thought that maybe she was responsible for his death." To ABC (Australian Broadcasting Corporation) News, Professor Abbott said, "The fact that she kept everything secret and turned this whole case into a mystery is part of the equation too."

Robin Thomson

At this time, Jestyn had a young son, Robin, who was not sired by the man she had married. (He was going through a divorce when their romance began.) According to The Northern Star, Robin went on to become a famous dancer with the New Zealand ballet. He would have been 16 months old when the Somerton Man died and could have been his son.

Robin had the same tooth and ear anomalies as the Somerton man. University of Adelaide professor of anatomy Maciej Henneberg, who examined pictures of Robin, noted to ABC News that the chance of having both these features was between one in 10,000 and 20,000. That he would coincidentally share these with the Somerton man is a more astronomical figure. "Therefore it is likely that the Somerton Man and the person suggested to be his son are actually related." If her daughter confessing what she knew hadn't been enough, such an odd trait being shared more than implies that maybe Jestyn was not being completely forthright about knowing the Somerton Man.

Robin died in 2009 and was cremated before a serious reexamination of the case began. Still, he had a daughter born of an affair with a ballerina named Roma from the Australian Ballet. They were unprepared for a child, so the ballerina had her baby and put her up for adoption.

Professor Derek Abbott

If one is researching the Somerton Man, they won't get far before hitting upon the exhaustive research and theories of Derek Abbott, a professor of electrical and electronic engineering at Adelaide University, who discovered the mystery in 2007. Per ABC News, he was reading a magazine in a laundromat, learned about the case, and essentially thought, "Hey, wouldn't this be fun to discuss with my students?"

It was a small question that would radically change the trajectory of his life.

According to Phys.org, he is driven by the moral imperative that everyone deserves to have a name. "Our individual identities are fundamental to being human," Abbott said, "Civilized societies always strive to preserve the identities of the dead, whether it be the result of accident, crime, war, or natural disaster."

He tried for years to get the government to agree to exhume the Somerton Man's body so that tests could be run that might better explain who he was. They said that he did not have a compelling interest in knowing — such as thinking that he might be related to the Somerton Man — so they wouldn't give him permission.

Rachel Egan

Rachel Egan did not discover until her early twenties that she was adopted. She had always been the odd one in her adoptive family. ABC Radio National quoted Rachel saying, "I always had a passion for ballet, and dance, and theatre and I always wondered where that came from," which makes a case for nature over nurture. Once she knew she was adopted, she moved closer to her birth mother, a woman named Roma, to get to know her.

Then she met Derek Abbott, whom she referred to as a "nerd," according to News.com.au. "He wanted to look at my ears and my teeth. He was also after my DNA," she said. "It's probably the first request I've had from a man to do that." (Her ears and teeth don't show her biological father Robin's anomalies.) A few days after they'd met, Derek proposed. Rachel accepted.

Roma found all this profoundly fishy, suggesting that Abbott only proposed to get to her DNA. Rachel said to ABC News, "I think there is some truth to that." In the end, she stayed with Abbott, causing her relationship with Roma to erode.

They married and had three children. It is unclear if the kids have ear or tooth anomalies or how they feel about ballet. Abbott told ABC Radio National, "The fact that my family is now entwined with the Somerton Man makes things perhaps a bit more complicated."

Exhuming the Somerton Man

Besides his probable descendants, Phys.org noted that the only DNA of the Somerton Man that Abbott and other investigators have had access to has been from hair samples in a museum. Abbott is specifically interested in the Somerton Man's autosomal DNA, which is at far lower levels in hair, particularly hair that is decades old.

Fortunately, the police understood when they were burying the man that they were disposing of some of their best evidence. They had him embalmed and then had the body placed under concrete in the dry ground in case they needed to examine it further later, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

Professor Abbott and others have continued to push for exhumation for years. Abbott, of course, thinks the Somerton Man is related to his wife (and now children), though Rachel isn't sure. The Advertiser reported that when Derek wrote to Attorney-General John Rau in 2011 to petition for an exhumation, he was rejected because there needed to be "public interest reasons that go well beyond public curiosity or broad scientific interest."

According to 7news.com.au, in 2019, South Australia's attorney-general finally granted conditional approval to exhume the body. However, per ABC News, one of the conditions was that taxpayers would not foot a penny of the $20,000 bill to do it, meaning that it has not been accomplished as of 2021.

Theories about the Somerton Man

Even the least exciting theory for the Somerton Man is fantastic: He killed himself using unidentifiable poison and eliminated all traces of his identity. According to the Government of South Australia Attorney-General's Department, Professor Cleland said, "in all probability [...] some poison had been taken, with suicidal intent [...] the words ["Tamám shud"] were put there deliberately and indicated that intention that he was fed up with things." According to News.com.au, neighbors claimed that an unknown man had knocked on Jestyn's door on November 30. Surely someone would have admitted to recognizing him by now.

Another theory is that the man — an ordinary fellow — heard something he should not have, which he cryptically notated in a copy of Rubáiyát. Whoever he overheard elaborately murdered him and then left clues to bring the police to a suitcase full of questions. The more popular theory is that the man was a spy. It was the beginnings of the Cold War, and an untraceable poison does seem like the last meal of an international spy.

The government has stonewalled those who try to get information. The Attorney-General's Department noted that, though the State Records Act 1997 should allow them access, "The Somerton Man case is still an open case, despite its age, and therefore we do not have police files relating to the case in our custody."

As late as 1978, according to Smithsonian Magazine, someone intermittently put flowers on the Somerton Man's gravestone in Adelaide's West Terrace Cemetery.

Clive Mangnoson

In 1949, per The Advertiser, Roma Mangnoson (not to be confused with Rachel Egan's mother) was almost hit by a car, and then "a man with a khaki handkerchief over his face told [her] to 'keep away from the police — or else.'" She believed this had to do with her husband Keith's attempts to claim that the Somerton Man was his former coworker. On June 6, Roma's two-year-old son Clive was found dead in a sack, next to his unconscious father. Both had been missing for four days. After a conversation with a detective at the hospital, Keith was transferred to a mental ward. Two politicians reported that they received calls stating that either they or Roma would meet with "accidents" if they stuck their noses "into the Mangnoson affair."

Who wanted to silence Keith badly enough to kill his child?

Keith suffered "war neurosis," according to The Chronicle. He had spent seven weeks in a "receiving home" the last time he disappeared for days without explanation. Keith only cared about Clive anymore and was found incoherent and shivering, his son dead by barbiturates, an empty pill bottle at the scene. It's not tricky calculus.

The Somerton Man was linked only because Keith claimed to have known him. The man who threatened Mrs. Mangoson told her not to go to the police — possibly about the attempted vehicular manslaughter. Also, Detective L. Bond suspected the threatening calls were a morbid hoaxer. No mysteries here, only tragedy.

George Marshall and Gwenneth Dorothy Graham

Months before the Somerton Man, the decomposed body of Joseph "George" Marshall was discovered on Taylor's Bay with Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám on his chest, according to Smithsonian Magazine. This was doubly suspect because his brother, David Marshall, became the first chief minister of Singapore.

The truth of the situation is more prosaic. Marshall's 1931 foray into poetry was a failure. After a previous suicide attempt at a beach, George was institutionalized. According to Global Histories, his treatments intentionally put him in comas where electroconvulsive therapy would be applied. Brain damage was a side effect. After insuring his life for a "very large sum," according to The Mirror, George had planned suicide. He was an ardent lover of the poems of Omar Khayyám. The underlined portion of his copy could be his suicide note.

At the inquest into Marshall's death, a woman named Gwenneth Dorothy Graham spoke. Thirteen days later, she was found facedown in a bathtub, her wrists slit — silenced by a shadowy cabal?

No. Graham said that she lived with her parents but had shacked up with a soldier, Helmut Hendon. George had "told her to break from Hendon, that he was evil." The night of Graham's death, Hendon had "suggested she leave the flat and go back and live at home." The Argus stated that she responded by going into the bathroom and committing suicide.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).