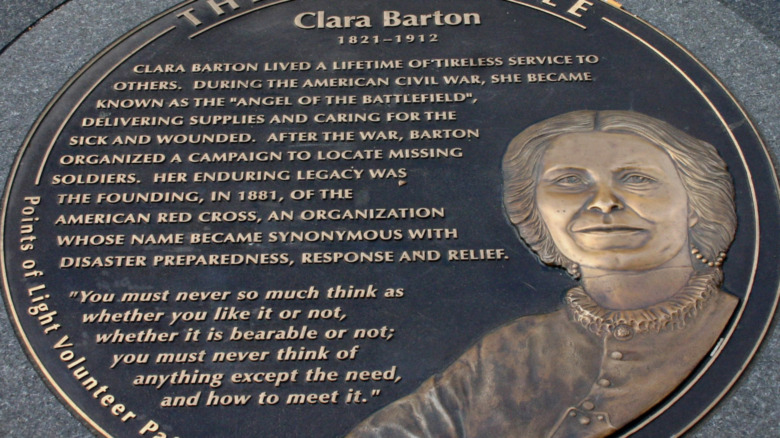

The Untold Truth Of Clara Barton

Any one of Clara Barton's achievements would be enough to guarantee her a place in history. She was one of the first women hired to work in the federal government. She became famous during the Civil War for beating the Union Army's surgeons to the battlefield, and for her attentiveness towards patients. After the war, she tracked down 22,000 missing Union soldiers. She brought the Red Cross and the concept of first aid to America. She was pivotal in amending the Geneva Convention to allow the Red Cross to attend natural disasters as well as war zones. She advocated for civil rights and women's suffrage.

The fact one person did all of this is astonishing. The fact that she was a woman operating at a time when women couldn't even vote and weren't expected (or permitted) to do much more than marry and have children makes it even more so. This is the untold truth of Clara Barton, the angel of the battlefield and beyond.

Clara Barton's first patient was her brother

Clarissa Harlowe Barton was born in Oxford, Massachusetts, on December 25, 1821, the youngest of five children by 10 years. Her father Stephen Barton was a farmer, captain of the local militia, and a member of the local government. He raised Clara on stories of his time fighting in the French and Indian War and on the Western frontier. He taught her battle formations and strategies, military etiquette, and politics. Clara wrote in her 1907 memoir The Story of my Childhood, "When later, I... was suddenly thrust into the mysteries of war... I found myself far less a stranger to the conditions than most women, or even ordinary men."

Another skill Clara picked up in childhood which helped with her war work was horse riding. Clara recalled that her brother David, who loved horses, taught her to ride when she was just five — and that she appreciated this later when she had to escape from a battlefield by horse.

David also inadvertently sparked her interest in nursing. When he fell from the rafters of a barn and sustained a serious injury, 11-year-old Clara spent two years in charge of his medical care. At the time, that meant leeches. Once David had recovered, Clara felt a loss of purpose that would haunt her for the rest of her life: if she wasn't helping someone, she often felt depressed, the Washington Post reports.

Clara Barton set up a school and worked at the U.S. patent office

When Clara Barton turned 15, she got her first job: as a teacher. And you thought your high school job was tough. Despite being incredibly shy, Barton proved to be a natural. Building on her instincts, in 1850, she went to New York to study the theory of teaching at one of the few teaching colleges that accepted women.

Two years later, degree in hand, she moved to Bordentown, New Jersey, where she convinced the local school board to let her set up a public school for boys who couldn't afford the local schools' fees. Sure she would fail, they let her. Under Barton, attendance grew from six to 600 in just one year. But while she was sick with laryngitis, the board replaced her with a man, whom she was supposed to assist.

Barton quit in protest and moved to Washington D.C. There she became one of the first women hired by the federal government when she got a job in the U.S. Patent Office as a copyist. As the Washington Post reports, she rose through the ranks for a few years, until a sexist boss launched a bullying campaign and had her fired in 1857. However, her efficiency and attention to detail were so missed, they brought her back three years later. That's where the war found her.

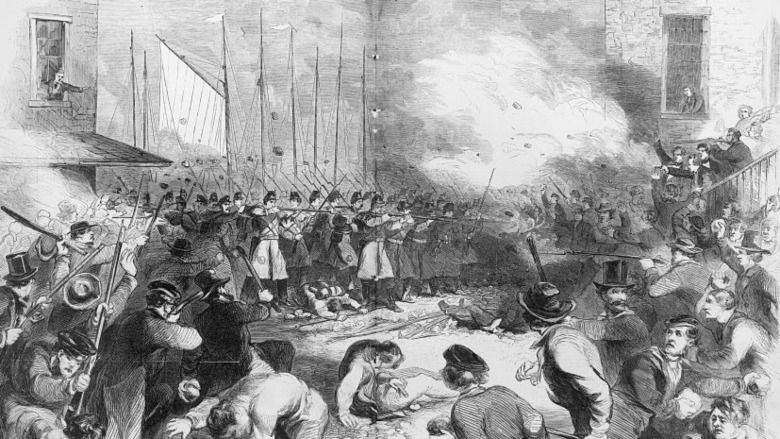

Clara Barton collided with the first official bloodshed of the Civil War

The American Civil War officially started on April 12, 1861, with the attack on Fort Sumter. A week later, the 6th Massachusetts Infantry was attacked in Baltimore while traveling through the city to Washington, D.C. Four soldiers were killed, 36 were wounded, and dozens of civilians died.

When the beleaguered regiment arrived in D.C., the unfinished Capitol Building was turned into a makeshift hospital to accommodate them. Clara Barton heard about the riot and the wounded men: according to the Washington Post, they included former students and people she'd grown up with. She also heard the people treating them had very few supplies. Not easily daunted, Barton collected essentials, including medical supplies, clothes, bedding, and food, and traveled to the Capitol. Given that there was no official training for nurses at the time, she had to learn on the job, as well as drawing on her experience caring for her brother David.

In addition to bringing the supplies, she recruited members of the public to send more, which she collected at her house. But possibly the most significant contribution she made to those on the wards was that she took the time to sit with them, talking and reading to them, praying with them, and helping them write letters home.

Clara Barton convinced the Union Army to let her travel with them

After working with the 6th Massachusetts Infantry, Clara Barton continued to nurse in hospitals and forts close to D.C. But when she started hearing stories of the appalling conditions on the front lines, she realized her services were needed closer to the battles. At that time, the Washington Post reports, the U.S. Sanitary Commission (USSC) was in charge of organizing nurses for the Union Army. The relief agency was founded by the U.S. government about a month after the Baltimore Riot to help the Medical Bureau support wounded and sick troops, and was largely run by women. However, government bureaucracy meant the effort was disorganized, and often arrived at battles dangerously late.

As an independent operator, Barton had more flexibility and speed. She pestered government officials to let her help, although in March 1862, she had to briefly return to Oxford to say goodbye to her dying father. Stephen Barton encouraged his daughter to throw her energy into helping the Union Army. And that August, she was finally given permission to travel to the battlefields.

Six days later, Barton arrived at a field hospital at the battlefield of Cedar Mountain, Virginia, with much-needed supplies. From there, she followed the Union Army, appearing at many of the Civil War's most famous and deadly battles, including the battles of Second Manassas, Antietam, Fredericksburg, and the Wilderness.

She narrowly avoided death multiple times

Clara Barton's close relationship with the Union Army meant she was often in the same danger as the troops — especially since she was frequently the first medic on the scene. Sometimes she and her supplies arrived while battles were still raging.

Her closest — but not only — brush with a bullet came at the Battle of Antietam, on September 17, 1862. According to the Washington Post, Barton and the other medics were caught up in heavy gunfire. The men assisting the surgeons abandoned their patients, but Barton stayed. While she was helping a wounded soldier sip from a cup of water, a bullet went straight through her sleeve, fatally injuring the man. Barton later wrote, "I have never mended that hole in my sleeve. I wonder if a soldier ever does mend a bullet hole in his coat?"

Like the soldiers, Barton was also at risk from illnesses that developed and spread thanks to the poor hygiene in the army camps. At Antietam she contracted typhoid fever, and was sent home to D.C. After recuperating, she returned to the battlefields. In 1863, stationed with the 54th Massachusetts regiment on Morris Island, Barton dodged shells to reach the wounded. After working around the clock without sleep for days, she eventually dropped from exhaustion, suffering from fever and diarrhea, and was sent to a nearby Union camp to recover.

Clara Barton earned respect from most of the men she worked with

You might know Clara Barton as the Angel of the Battlefield. She was given the nickname early in her Civil War career, by Union Army surgeon Dr. James Dunn, who worked alongside Barton during multiple battles. In a letter to his family that was later published by newspapers around the country, Dr. Dunn wrote that Barton had managed to arrive at every major battle just as the surgeons were desperately low on supplies. He reported she tended to the wounded in the field hospitals, supplying them with clothes and soup, and worked around the clock. He wrote, "In my feeble estimation, Gen. McClellan, with all his laurels, sinks into insignificance beside the true heroine of the age, the angel of the battlefield." The nickname stuck.

It wasn't just doctors who appreciated Barton's services. In 1864, General Benjamin Butler (most famous for the so-called "Contraband Decision") named Barton head nurse of the Army of the James, the Washington Post reports. The fact she didn't have any official medical training didn't detract from her suitability for the title.

However, not everyone was won over by her courage and skill. According to the Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Museum, when Brigadier General Gillmore dismissed her from Morris Island, Barton wrote in her diary that she felt he saw her as "some frail creature who could not endure hardship."

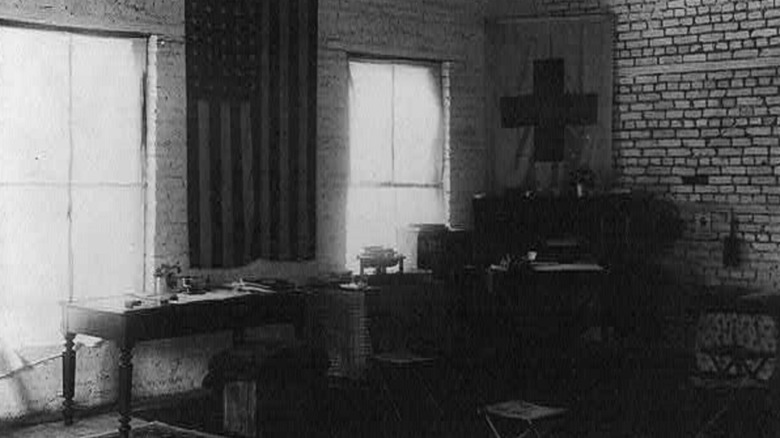

Clara Barton helped uncover the fates of over 22,000 missing soldiers

By the time General Lee surrendered on April 9, 1865, Clara Barton had already found her next undertaking. In March, she'd turned her attention to helping worried families find out what had happened to the thousands of missing soldiers. According to the National Parks Service, over half of the dead Union soldiers were buried in unmarked graves, with no official record of what had happened to them.

Barton was appointed General Correspondent for the Friends of Paroled Prisoners by President Lincoln. Operating from her apartment in D.C., she and a small staff checked lists of prisoners and casualties, establishing the Bureau of Records of Missing Men of the Armies of the United States. They published lists of missing men that went out nationwide. Sources differ on how long the office ran for: the Red Cross and PBS say four years, and the Smithsonian says two. But by the time the Missing Soldiers Office closed, Barton and her team had answered over 63,000 letters and clarified the fates of 22,000 men.

Barton also worked to identify Union soldiers buried in graves marked only by numbers at the notorious Andersonville Prison in South Carolina. With help from lists copied and hidden by former prisoner Dorence Atwater during his incarceration, Barton was able to add names to nearly 13,000 of the graves and inform the soldiers' families. She was also instrumental in turning the prison into Andersonville National Cemetery.

She joined the Franco-Prussian War while on vacation

If your idea of a vacation involves relaxing by a pool or sightseeing, you would not have made a good travel companion for Clara Barton. By 1869, the year she closed the Missing Soldiers Office, Barton was suffering from exhaustion. Her doctor prescribed a trip to Europe, with the idea being that she would take some time to relax away from the desolation wrought by the war. Instead, the trip sparked Barton's next big campaign.

In Switzerland, according to PBS, she met members of the International Federation of the Red Cross. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) had been founded in 1863 by Henry Dunant, who proposed bringing together an international group of volunteers to treat and protect civilian and military casualties of war. The Geneva Convention, based on Dunant's ideas, was signed by 12 European nations in 1864. Somewhat ironically, America had been too preoccupied with the Civil War to sign the treaty.

Barton immediately saw value in bringing the Red Cross to America. But first, she decided to accompany them to the battlefields of the Franco-Prussian War, which started in 1870. Barton offered the same care she'd shown to American soldiers, and also organized factories that hired women to make clothes. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this work did not provide the rest her doctor had ordered. Her health started to fail and after a brief trip to England to recover, she returned to America in October 1873.

Clara Barton launched the American Red Cross

It took Clara Barton four years to recover enough to resume her humanitarian work. After arriving back in the U.S., her mental health was further impacted when her sister Sally died on May 24, 1874. But in 1877, she began a campaign to establish the Red Cross in America. There was a major difference between Barton's version and the European originators: the American Red Cross would also help with peacetime disasters. The Geneva Convention was officially amended to include this stipulation in 1884.

Barton started raising awareness of the Red Cross' mission among the general public and political higher ups. Her wartime nursing and missing persons work had earned her access to President Hayes himself, whom she tried to convince to sign the Geneva Convention. Hayes declined to commit to an international treaty, and Barton later moved on to his successor, President James Garfield, who was elected in 1881. That year, Barton officially established the American Red Cross, and Garfield seemed likely to sign the convention. But less than a year into his presidency, he was assassinated. Fortunately for Barton, his replacement Chester A. Arthur signed the treaty.

The earliest work the American Red Cross got involved in revolved around natural disasters, including Michigan forest fires in 1881; the Johnstown flood in Pennsylvania in 1889; a hurricane in the South Sea Islands of South Carolina in 1893; the Galveston hurricane in Texas in 1900; and the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

Clara Barton was forced to resign from the Red Cross

Clara Barton continued to throw herself into her work. Being the founder and president of the Red Cross — not to mention being in her sixties and seventies — could have guaranteed her a cozy office job, with the occasional speech. But as the Washington Post reports, she personally led the organization's efforts in several large disasters, including the Johnstown flood.

When the Spanish-American war broke out in 1898, Barton was in Cuba leading the Red Cross' efforts to help the civilian population, who were being forced into camps by the Spanish. Barton, then 77, worked 16-hour days distributing food, clothing and medical supplies, and creating homes for orphans. During the war, she and the American Red Cross treated the injured on both sides of the conflict, despite resistance from the U.S. military.

However, Barton's hands-on approach wasn't always appreciated, even within the Red Cross. While she was excellent in a crisis, at the office she was a demanding boss, but also reluctant to delegate. She was accused of mishandling the organization's finances, to the point that the treasurer resigned in protest in 1902. Loyalties were divided between Barton and internal rival Mabel Boardman. After several years of this, during which time President Roosevelt sided with Boardman, Barton finally resigned as president of the Red Cross in 1904.

She supported civil rights and suffrage

Although Clara Barton is more famous for her humanitarian work, she also supported civil rights for African Americans, and the women's suffrage movement.

Barton opposed slavery when she joined the war effort, but was not a passionate abolitionist. However, in 1863, she witnessed the courage of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, the Black regiment that attempted to capture Battery Wagner. It woke Barton up to the diabolical injustices of slavery and racism. As the Washington Post reports, when Barton went on a fundraising lecture tour between 1866 and 1868, in addition to talking about her Civil War experiences, she advocated for the rights of formerly enslaved people. She even shared a stage with Frederick Douglass and abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison.

Barton had been putting the principles of the suffrage movement into practice her whole life. While she was willing to volunteer — and even spend her own money — for worthy causes, she refused to be paid less than a man doing the same job. And during the war, when many army surgeons would only work with male nurses, Barton proved women were as courageous and competent as men under fire. Barton was friends with famous suffragette Susan B. Anthony, lectured about suffrage, and was a member of women's rights organizations. However, she controversially opposed adding a clause effectively granting women the right to vote to the Fifteenth Amendment, because she feared it would derail the entire endeavor and prevent Black men from getting the vote.

Clara Barton didn't do retirement

By now, it won't surprise you to learn that when Clara Barton left the Red Cross, aged 82, she didn't settle happily into retirement.

In addition to giving speeches, in April 1905 she founded the National First Aid Association of America, with the intention of teaching everyone in the country basic emergency first aid. They especially focused on workers in mills, factories and railroads, and fire departments, but also offered courses to the public, and sold first aid kits. Barton remained honorary president of the organization for five years. The Red Cross even started teaching similar lessons, but Barton didn't mind. The National Park Service writes that she responded: "I should rejoice the crop no matter who harvests it."

At the insistence of various friends, Barton also wrote a book about her early adventures, The Story of My Childhood, published in 1907. Since 1897, Barton had been living in Glen Echo, Maryland, northwest of D.C., in a house that had been gifted to her by real estate developers the Baltzley Brothers, according to the National Park Service. Her health gradually started to fail, but when she died aged 90 on April 12, 1912, it still felt sudden to her friends and family, who were so used to Barton being the nurse and not the patient.