The Untold Truth Of Dorothea Puente, The Death House Landlady

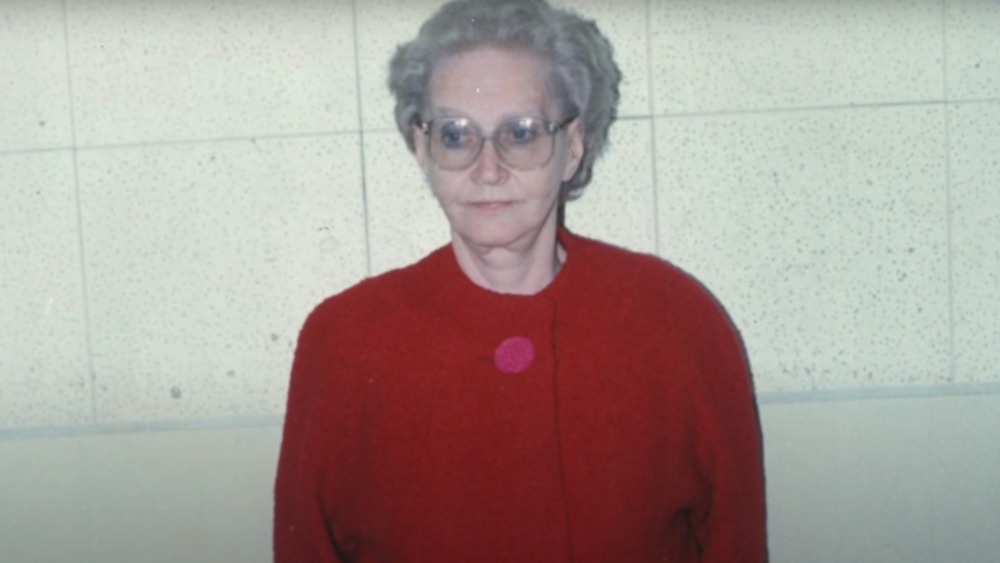

In 1993, many residents of Sacramento were shocked when they realized that an old woman was behind a series of murders in her own boarding house. Known as the "Death House Landlady," Dorothea Puente targeted elderly and disabled people, especially those who were already houseless or didn't have a strong support system. Her crimes ranged from drugging and robbery to check forgery and murder, and even when she was blatantly violating her parole, she managed to fly under the radar. Puente also wasn't as old as she looked, often claiming to be at least 15 years older than she actually was.

Although Puente was eventually charged with the murder of nine individuals, it's likely that there were more victims. However, since many of her victims were houseless or otherwise vulnerable individuals, it's impossible to determine an exact number.

Puente's early life is also difficult to pin down because she was known for exaggerating and being a pathological liar. This piece follows what appears to be the most accepted timeline of Puente's life, but some things remain known only to Puente herself. This is the untold truth of Dorothea Puente, the Death House Landlady.

Dorothea Puente's early life

Dorothea Puente was born Dorothea Helen Gray in Redlands, California, on January 9, 1929. She was the sixth of seven children born to Trudy Mae Gates and Jesse James Gray, whose "lungs were damaged from a gas attack" while fighting in World War I. However, according to the Los Angeles Times, there are conflicting reports about Puente's early life, with some accounts claiming that she was one out of 18 children.

Puente and her family moved to Los Angeles in the 1930s to be closer to a veterans' hospital, but her father's condition continued to deteriorate. "Sometimes [he] held a gun to his head and threatened to kill himself in front of his children," wrote the LA Times. Meanwhile, Puente's mother did sex work to support the family.

By 1937, Puente's father had passed away, and her mother lost custody of the children. The following year, she died in a motorcycle accident. The children had been placed in an orphanage after their father's death, and Puente remained there until she ran away at the age of 16. At one point, she tried to earn a living as a sex worker in Washington state.

According to Radford University, both of Puente's parents suffered from alcoholism, and Puente experienced physical abuse while they were alive and was often underfed. During her trial, a witness also testified that Puente was sexually abused during her time at the orphanage.

Dorothea Puente's marriages and arrests

When Dorothea Puente was 17 years old, she married 22-year-old GI Fred McFaul, and they moved to Gardnerville, Nevada. The marriage only lasted two years. During that time, it appears that they had two children together, although one was sent to live with relatives and the other was put up for adoption. Some reports say that McFaul died of a heart attack, while others state that he left Puente, possibly after she had a miscarriage.

According to Serial Killer Timelines by Chris McNab, after her first marriage ended, Puente became involved in criminal activity. "In 1948, she stole some government checks and used them to buy clothes" in San Bernardino. Puente was caught and convicted of forgery, and after serving six months of a four-year sentence, she was released. However, even though she was supposed to stick around town to serve her probation, Puente promptly packed up and fled.

Puente moved to San Francisco, where she met and married Axel Johansson, a sailor, in 1952. Although their marriage lasted over ten years, most accounts agree that it was an unhappy and violent relationship.

Dorothea Puente was briefly committed

Axel Johansson was often at sea for months on end, and while he was away, Puente resumed working as a sex worker. Johansson wasn't pleased to find this out when he returned, so they would frequently argue as a result, often about Puente's gambling and drinking as well.

During this time, according to Radford University, Puente was arrested for vagrancy, which was the charge often levied against sex workers. Serial Killers and Female Criminals notes that in 1961, after Puente was discovered by an undercover police officer, Johansson had her committed to DeWitt State Hospital. There, Puente was described as having an unstable personality, and she was prescribed an antipsychotic for the first time. However, "it's unlikely Dorothea received any psychological counseling," and there's no record of a clear diagnosis from the facility. Although Puente was later described as schizophrenic, this used to simply be a catchall term to describe inexplicable behavior.

Puente didn't stay in the facility long, and upon her release, she and Johansson moved to Broderick, California. But her behavior didn't change. In 1963, after Puente found it harder and harder to secure clients herself, she transitioned into becoming a madam who ran a brothel, which led to another arrest, though she avoided a pimping charge. In 1966, she and Johansson divorced.

Divorce after divorce

Dorothea Puente got married two more times after her divorce from Johansson, but neither one of those marriages lasted long. According to All That's Interesting, in 1968, Dorothea married Roberto Puente. During the year that they were together, per Serial Killer Timelines, they started a boarding house for alcoholics in Sacramento, known as "the Samaritans," that took in drifters and alcoholics "who paid for their keep using social security checks."

Serial Killers and Female Criminals claims that Puente "realized that there was an untapped population of alcoholics, senior citizens, and chronically ill people who were in need of care and, more importantly, [...] received government money." Those who stayed at the boarding house signed their checks directly over to her, while Puente claimed that she was doing this to protect the residents.

By the time the marriage ended, Puente claimed that the business had amassed a debt of $10,000. Nevertheless, she would come back to this business model. After leaving Roberto, Puente married Pedro Angel Montalvo, but the marriage only lasted a week.

Dorothea Puente's boarding house

After declaring "the Samaritans" bankrupt, Dorothea Puente promptly set up a new boarding house on 2100 F Street in a large 16-bedroom Victorian house in the early 1970s. In Female Serial Killers, Peter Vronsky details how Puente hosted a dinner for social workers and the residents who suffered from alcoholism every few weeks "where the quality of her food and care was put on display."

The social workers knew that Puente had a tendency to exaggerate, but they didn't realize that she was also pretending to be a doctor. First, she hung up fake medical diplomas and sat in on checkups with residents. But soon, in the predominantly Hispanic neighborhood, Puente started going around as if she were a doctor, offering "vitamin" injections and medical advice to local residents.

For a while, social workers looked past what they considered to be Puente's "eccentricity" and admired her for dealing with "tough cases." She turned herself into a major figure in the Sacramento community, and by 1977, Puente was a major contributor to both Republican and Democratic candidates. During one fundraiser, she even danced with California Governor Jerry Brown.

But in 1978, her house of cards started to falter. The Los Angeles Review of Books writes that Puente was arrested and convicted "of forging her tenants' signatures on their benefits checks." She was given five years of probation, which included the stipulation that she was forbidden from running a boarding house.

Steadily pushing the limits

After her conviction, Dorothea Puente started working as an in-home caregiver, and over the next four years, she kept coming up on people's radar. In Female Serial Killers, Vronsky writes how Puente's patients often ended up in the hospital, and Puente's name kept coming up to the same doctor who treated the patients. "Yet despite the fact that Dorothea was on everybody's radar, nothing was done. Some social workers and doctors, aware of the problem, steered their clients and patients away from Dorothea, but officially absolutely nothing was done."

In 1982, Puente picked up a man in a bar, and they went back to his apartment together. Once there, Puente drugged him. The man was left conscious but paralyzed, and he watched Puente rob his apartment. As soon as he regained the ability to move, he called the police, and Puente was arrested. But Puente presented herself as a harmless old woman who was given gifts, and the police let her out on bail.

This wasn't the first time she had drugged and robbed someone. In fact, by that point, Dorothea had been arrested and released on bail four times. This time, she was tried for grand theft, robbery, and forgery. During the preliminary hearing, she was even re-arrested for another set of check forgery charges from an additional victim. But once more, she was released on bail.

Who was Dorothea Puente's first victim?

Around this time, Dorothea Puente became business partners with Ruth Monroe, a 61-year-old woman. According to Female Serial Killers, Monroe didn't know a thing about Puente's legal troubles and had simply agreed to start a catering business with her, since Puente's cooking skills were well-regarded.

On April 11, 1982, Monroe also moved in with Punente, ostensibly to "save on expenses" since Monroe's husband had entered into hospice care. On April 28, Monroe was dead. After an autopsy was done, medical examiners found a large amount of codeine in her system, and although her death was labeled "undetermined cause," it was believed to be a suicide.

Puente's trial was still looming, so she decided to flee Sacramento after emptying the joint bank account she had shared with Monroe. After drugging and robbing a former patient, Puente bought an airplane ticket to Mexico. However, she was arrested before she could board the plane, and this time, her lawyer wasn't able to argue that she wasn't a flight risk.

Puente was sentenced to five years for "drugging elderly people and stealing their benefit checks" on August 19, 1982. Although Monroe's family told the district attorney of their suspicions, the DA decided that since the death looked like a suicide and Puente was already jailed, there was no point in pursuing a conviction.

Ultimately, Puente was never convicted in relation to Monroe's death.

Meeting Everson Gillmouth

While in prison, Dorothea Puente started corresponding with 77-year-old Everson Gillmouth through a pen pal exchange for imprisoned women. Gillmouth lived in Oregon, and when Puente was released after serving three of her five years, he drove out to pick her up at her halfway house in Fresno. Together, they moved back to Sacramento.

The Los Angeles Review of Books writes that "Puente was released in 1985, under the terms of parole that she not handle other people's social security checks or work with the elderly. She immediately began doing both of those things." She and Gillmouth moved into 1426 F Street, where Puente opened up a boarding house again. She took in vulnerable elderly tenants, many of whom struggled with addiction or mental illness, and targeted those "without strong social networks."

Between 1985 and 1988, Puente is believed to have murdered at least seven people who lived at her boarding house. And since she never reported their deaths, "their social security checks continued to come in, and Puente continued to forge their signatures and collect the cash."

Gillmouth disappeared not long after he and Puente moved to F Street. According to California Dreaming, Puente kept cashing his pension checks and writing to his family as though Gillmouth was alive. But in fact, it's believed that Puente murdered Gillmouth in late November or early December 1985. Afterward, she gave Gillmouth's red pickup truck to Ismael Florez, a carpenter she'd hired, and got him to unknowingly dispose of Gillmouth's body in a river.

Parole officers visited Dorothea Puente's boarding house at least 15 times

Despite the fact that parole officers visited Dorothea Puente's boarding house numerous times and were aware of the stipulation that she stay away from elderly people and not handle government checks, nothing ever happened. Culture Crossfire claims that parole officers made no fewer than 15 visits to Puente's home.

Even when someone disappeared from the boarding house, Puente was ready with an excuse. If anyone had their suspicions, they didn't voice them. According to LARB, the only person who seemed to notice something was Brenda Trujillo, Puente's former cellmate, who lived at 1426 F Street briefly.

On November 29, 1987, Trujillo wrote a letter to the Social Security Administration detailing her suspicions that Puente was stealing her SSI checks. But unfortunately, "living on the fringes, in and out of police custody for heroin and [sex work], Brenda wasn't taken seriously."

Meanwhile, Puente started saying that she'd "adopted" a man she called "Chief," a houseless man who suffered from alcoholism, and claimed that he was going to be the handyman. But after installing a concrete slab in the boarding house basement and one over the foundation of the garage, "Chief" disappeared.

Uncovering the bodies

It wasn't until Alvaro "Bert" Montoya disappeared that Dorothea Puente's house of death was finally addressed. Like many of Puente's vulnerable tenants, Montoya had developmental disabilities and schizophrenia, and after he didn't show up to meet with his social worker, Judy Moise, in November 1988, Moise reported him missing. Moise initially asked Puente where Montoya was, but Puente gave conflicting stories. At one moment, he was said to be in Utah, while at another, she claimed that he went back to Mexico, despite the fact that he was from Costa Rica, writes LARB.

When police officers first came to search for Montoya in Puente's house, they didn't find anything suspicious. But at one point, "a tenant named John Sharp quietly flashed a note to a detective," which read "She wants me to lie to you." A few days later, police returned with a warrant and asked Puente if they could dig in the backyard, where they saw recently disturbed soil. According to All That's Interesting, Puente "told them that they were welcome to do so, and even provided an extra shovel."

Seven bodies were discovered, belonging to Bert Montoya, Leona Carpenter, Dorothy Miller, Benjamin Fink, James Gallop, Vera Faye Martin, and Betty Palmer. Apparently, Puente's neighbors had been complaining about the smell and flies coming from Puente's backyard since May.

Dorothea Puente tries to flee

While the police were digging, Dorothea Puente asked if she could run out to buy a coffee. Since she wasn't a suspect at the time, police said yes, at which point Puente promptly left the house and fled to Los Angeles.

According to Sactown Magazine, "Puente's vanishing ignited a manhunt that stretched to Mexico," and it took police five days to track her down. While staying at the Royal Viking Hotel in Los Angeles, Puente tried to go back to her old technique of picking up men at a bar and then proceeding to drug and rob them. But her reputation had caught up with her, and her face was all over the news.

Using the name Donna Johnson, she approached Charles Willgraves at a bar, but once Willgraves realized why "Donna" looked familiar, he called the police. Puente was arrested, returned to Sacramento, and held without bail.

Dorothea Puente was charged with nine murders

Dorothea Puente was charged with the murders of the seven individuals whose bodies were found in her backyard, as well as the murders of Ruth Monroe and Everson Gillmouth, whose body remained unidentified until police connected it to Puente.

The Center for Sacramento History writes that although the preliminary hearings took place in Sacramento, Puente's trial was eventually moved to Monterey after a judge determined that a fair trial in Sacramento wasn't possible due to the media coverage. Despite the fact that 130 witnesses were called during the trial, "the evidence was mostly circumstantial." Although lawyers showed that Puente had gotten dozens of prescriptions of the sedative Dalmane between 1985 and 1988 and that all of the bodies had Dalmane in their system, there was no concrete proof that Puente had been the one to administer the drugs.

According to Sactown Magazine, the jury deliberated for 24 days, "the longest deliberation in a murder case in state history," and convicted Puente on three out of the nine killings in August 1993.

Life without parole

Dorothea Puente was sentenced to life imprisonment without parole in December 1993. Sactown Magazine reports that Puente "granted few interviews [after the trial], observing a self-imposed gag order," and she maintained her innocence to her death, claiming that all the residents had died of natural causes.

She once stated, "The only time they were in good health was when they stayed at my home. I made them change their clothes every day, take a bath every day and eat three meals a day. These were people — the Salvation Army wouldn't take them. When they came to me, they were so sick, they weren't expected to live."

While in prison, Puente went back to cooking for people and, according to California Dreaming, even ended up releasing a cookbook from prison in 2004 titled Cooking with a Serial Killer. Apparently, "Most reviewers [say] the recipes are pretty basic, but tasty." The book also featured artwork that she'd done in prison as well as stories from her life.

Dorothea Puente remained imprisoned at the Central California Women's Facility in Madera Country, California, until she died at the age of 82 in 2011.