The True Story Of The Fire That Destroyed The Library Of Congress

To many, the Library of Congress must seem like an unassailable institution. It's been there practically forever, acting as the nation's biggest library. In fact, it's one of the largest libraries in the world, with over 170 million items in its collections, according to the Library of Congress itself. It boasts a world-class collection of rare books and has the largest known collection of audio recordings, maps, and films, among other materials. And it's all accessible not only to the Congressional representatives who work nearby in the Capitol, but to all Americans and members of the public.

But, the Library of Congress hasn't always been that way. In fact, its existence as an institution has been threatened by numerous obstacles throughout its more than 200 years in existence. According to History, those issues included not only organizational and budgetary complaints, but dramatic threats like fire. All told, the Library of Congress has been threatened by major fires at least three times in its history.

Perhaps the worst was an 1851 blaze that destroyed a large portion of the library's collection, kicking off an era of stagnation and existential worries for the Library of Congress that wouldn't resolve until decades later. And that's considering an even earlier disaster, where British troops burned down the Capitol and Library of Congress in 1814. This is the true story of the fire that destroyed the Library of Congress.

The Library of Congress was already an established institution by 1851

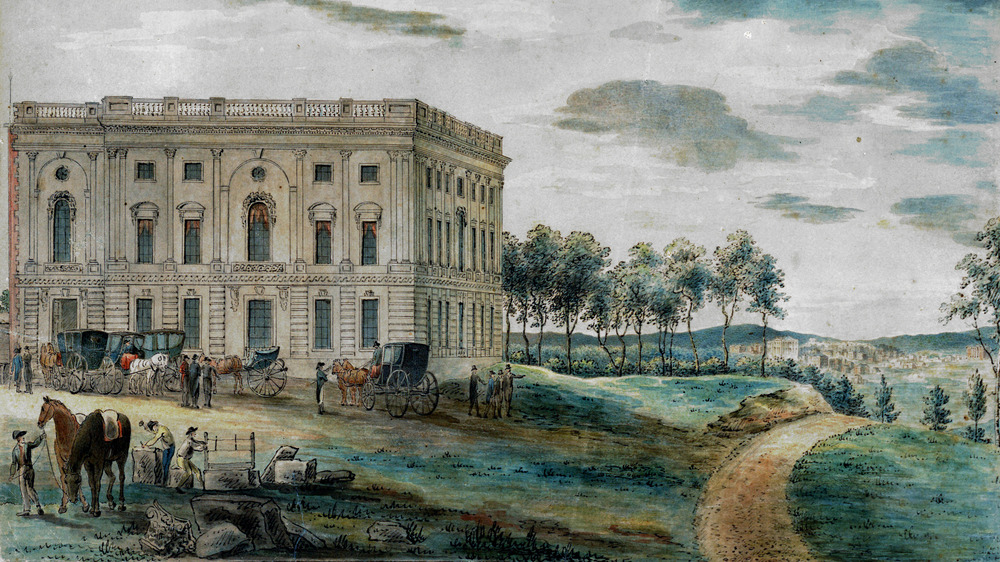

By the time of the 1851 fire, the Library of Congress had already been around for five decades. According to the Library itself, the institution was established in 1800 for the use of members of Congress — not the public. That's the same year that the United States government moved from Philadelphia to Washington, D.C., when Congress and President John Adams agreed on a $5,000 budget for the nascent library. Two years later, President Thomas Jefferson made the post of Librarian of Congress a presidential appointment, not unlike other appointed positions such as Supreme Court justices and U.S. ambassadors.

The sentiment of the Library of Congress was at least partially in line with those of many of the United States' first political leaders, who believed that intellectual empowerment was key to establishing a strong and long-lasting republic — but who didn't always seem to make that knowledge and power accessible to everyone who didn't look like them.

For nearly a century, the Library of Congress was typically housed in the same buildings as the actual Congress. It wouldn't get its own building until 1897, after multiple fires had damaged the collections.

This wasn't the first time the Library of Congress burned down

Throughout its history, the Library of Congress has faced multiple fires. However, its first conflagration took place in the midst of a dramatic attempted invasion of Washington, D.C., meaning that the initial burning of the Library is often overshadowed by the burning of practically the whole city.

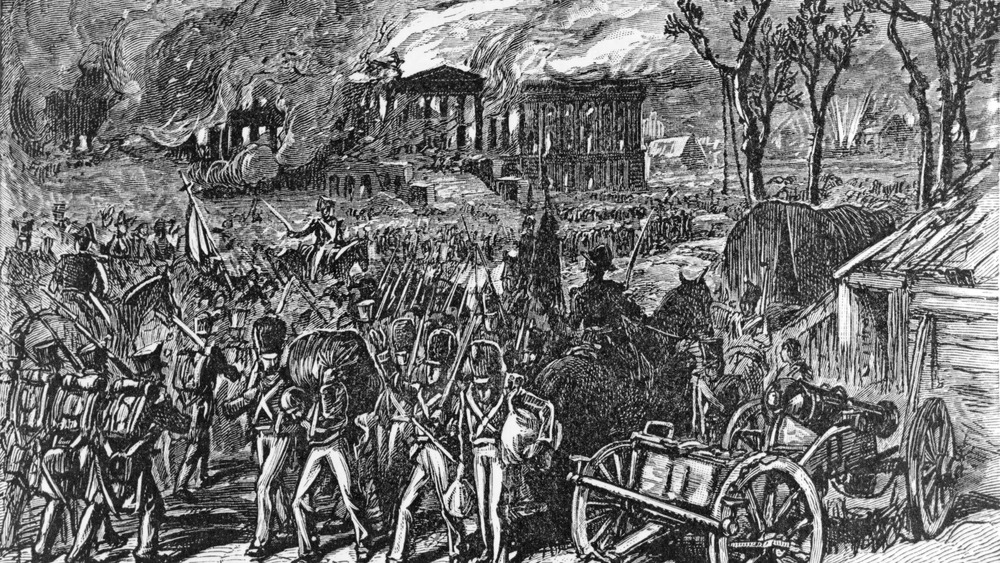

It all happened during the War of 1812, though the actual events under examination took place in 1814, while the war was still ongoing. In that year, reports The Conversation, British troops had entered the U.S. capital after years of negotiations over maritime rights and wars with other nations had gummed up the works, even though war had been officially declared in 1812. Meanwhile, the Americans had been attempting to overtake part of British-held Canada, destroying parts of York in what's now Toronto.

British forces easily made it to Washington, D.C., met by poorly-organized resistance and empty government buildings, as many American leaders had fled. According to the Library of Congress, troops torched a number of public government buildings, including the President's House and the Capitol, using a combination of gunpowder and rockets. The Library of Congress, housed inside the Capitol, burned as well.

Some wonder if the first Library of Congress may have survived the War of 1812

Dramatic as it may have looked, the burning of Washington, D.C. was largely symbolic, The Conversation argues. The city didn't have an especially large population and, since much of the U.S. government had fled before the British could overtake them, there was little strategic value in the destruction.

But try to tell that to the people who were trying to get out of Washington before coming face to face with the redcoats. As British troops advanced on Washington, some people attempted to save the Library of Congress' contents, along with other Congressional records, by frantically loading them into wagons and taking them out of the city. According to the White House Historical Association, clerks of the State Department gathered up documents that included the U.S. Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, and the Bill of Rights.

Some accounts indicate that the clerks may have also saved at least some of the first Library's collections, according to the Library of Congress. Two clerks, S. Burch and J.T. Frost, later attested that, yes, some of the books had been burned, but that they were only duplicates of books that they had already spirited away to some safe place in the country. Yet, other sources from the time maintain that the entire library collection had been incinerated. It's possible that Burch and Frost did save at least some books, but if they did, those volumes apparently disappeared in 1814.

Thomas Jefferson helped to rebuild the Library of Congress with his own books

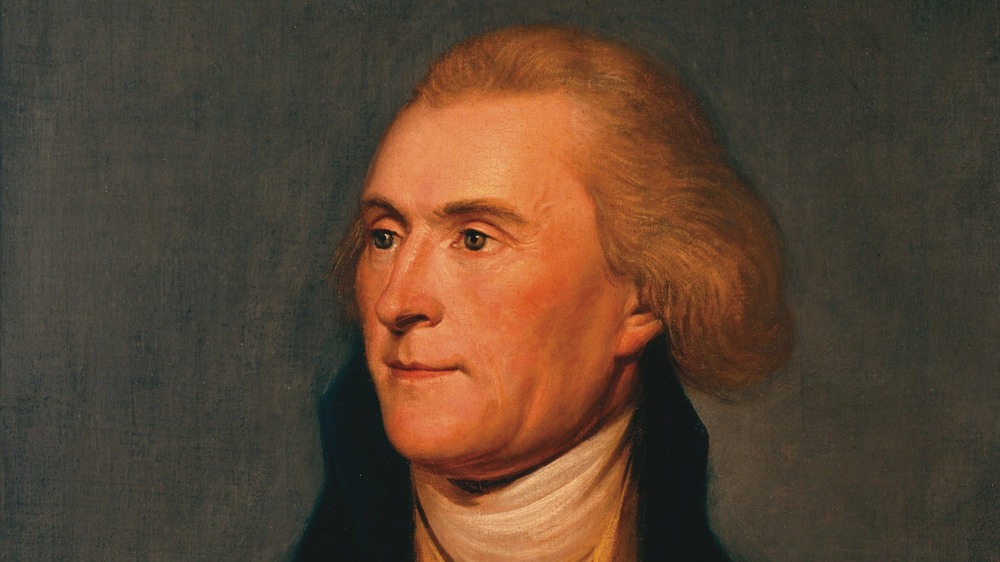

Once the fires died down, the British left Washington, and the American lawmakers returned, it was time to rebuild. While Congress was putting itself back together, it became clear that most wanted the Library of Congress to return as well. Former president Thomas Jefferson stepped in, offering to sell his own library to reconstitute the one lost in 1814.

It certainly makes sense that Jefferson was the one offering up such a deal. According to the Library of Congress, he was an inveterate bookworm and lifelong learner with an immense personal library. While he certainly seemed dedicated to the idea of having an informed, intellectual Congress, Jefferson may have also sympathized on a deeper level. In 1770, his own home had burned and Jefferson, staring at the ashes, most keenly felt the loss of his books. Later, he would come to own the largest private library in the United States.

While Jefferson clearly had an intellectual and emotional investment in rebuilding the Library of Congress, he also stood to benefit financially. According to Monticello, Jefferson struck a deal to sell 6,707 volumes to Congress for $23,950. Adjusted for inflation, that comes out to somewhere in the neighborhood of $400,000 US dollars today (via CPI Inflation Calculator). Given that Jefferson shortly turned around and used a significant portion of the cash to settle his own debts, there's no doubt that he had a financial incentive.

The Library of Congress suffered a second fire in 1825

Though the 1814 burning of Congress and its library stands as one of the largest and most dramatic destructions in Library of Congress history, it wasn't the only fire to damage the collections. Another struck in 1825, barely a decade later and still within living memory of many Americans who witnessed the first burning.

According to the United States House of Representatives, the 1825 fire took place on the evening of December 22. That's when Massachusetts Representative Edward Everett, who was leaving a nearby party, saw a strange light coming from the library windows. When he told a Capitol police officer, who didn't have a key, Everett was dismissed. Yet, as the glow got brighter and brighter, it became more difficult to ignore. Finally, more officers, along with Librarian of Congress George Watterson, discovered the terrible truth: the Library of Congress was on fire. Again.

Representatives and firefighters both fought the blaze, including Everett's fellow Massachusetts representative, Daniel Webster, and Tennessee politician Sam Houston. They put out the fire before it spread to the rest of the Capitol. Ultimately, it became clear that the culprit was a candle left in the room. Damage wasn't nearly as extensive as the 1814 fire, though some books and a rug were lost.

The Library of Congress was a fire simply waiting to happen

As the U.S. House of Representatives reports, the 1825 fire pushed Congress to ask the Architect of the Capitol to look into flame retardant materials to be used in Congress, though it appears that little real progress was made. After all, how could the 1851 blaze have happened if the appropriate fire suppression measures had been taken in the aftermath of the second Library of Congress conflagration?

Part of the issue were the materials that made up the core of the Library of Congress collection. The Library was crammed full of dry, flammable paper. It was also housed in various locations in the Capitol building for much of its early history, in a time when neither the Capitol nor any other structure at the time had a serious fire suppression system.

Perhaps even more alarming, at least to 21st century minds, is how buildings were heated at the time. According to Curbed, one of the most common methods of heating a building throughout the 19th century were, simply, fireplaces. Some homes could be outfitted with more advanced Franklin Stoves, while others employed a somewhat more efficient "Rumford fireplace," both meant to project heat back into a room. It's hard to deny the role of 19th century heating in the 1851 fire. According to Roll Call, the cause of that blaze was eventually determined to be a faulty chimney in the Library.

The 1851 fire was devastating to the library's collections

With a faulty chimney and stacks of paper everywhere, the Library of Congress was really little more than a fire waiting to happen. And happen it did, yet again, on December 24, 1851. As the local newspaper The National Era reported at the time, all of Washington, D.C. was "intensely excited by the great calamity" that befell the library. That morning, the captain of the Capitol Police opened up the library as usual but, two hours later, the smell of smoke was unmistakable. And, once the officer opened up the doors to the library to check, the massive flames made it all pretty clear.

Firefighters were promptly called, but, since there had been a large blaze just the night before, they were apparently quite tired and slow to make their way to the Capitol. The fire was eventually put out and all nearby people were safe, but the collections were devastated. According to History, about two-thirds of the books, papers, artworks, and other parts of the Library of Congress holdings were utterly destroyed by the flames and the sooty smoke.

Many of Thomas Jefferson's donated library books were also assuredly destroyed, though it's clear that not all of his books were lost. As per the Library of Congress, a portion of Jefferson's books, including an 18th century copy of the Quran, are still in the library's special collections today.

Congress got a little stingy when it came time to replace the Library

In the aftermath of the 1851 fire, it was clear yet again that the nation needed to rebuild its Library of Congress. After all, the institution had suffered what was quite possibly its biggest blow, according to the Library of Congress. Soon after the flames had been put out by the slow-moving firefighters and the remnants of the library had been cleaned, congressional lawmakers agreed that they should allocate funds to buy more books.

Yet, it was more complicated than simply handing a check over to the Librarian of Congress. It's true that, in 1852, Congress set aside $168,700 to replace the lost books. While that was undoubtedly generous for the time, "replace" is the key word here. There was to be no effort to grow the Library of Congress, meaning there were to be no new acquisitions and certainly no grand plans for changing the course or focus of the library. That conservatism was emphasized further over the following years, as the library stopped receiving copies of newly copyrighted books and other documents, further slowing the growth of Congress' library.

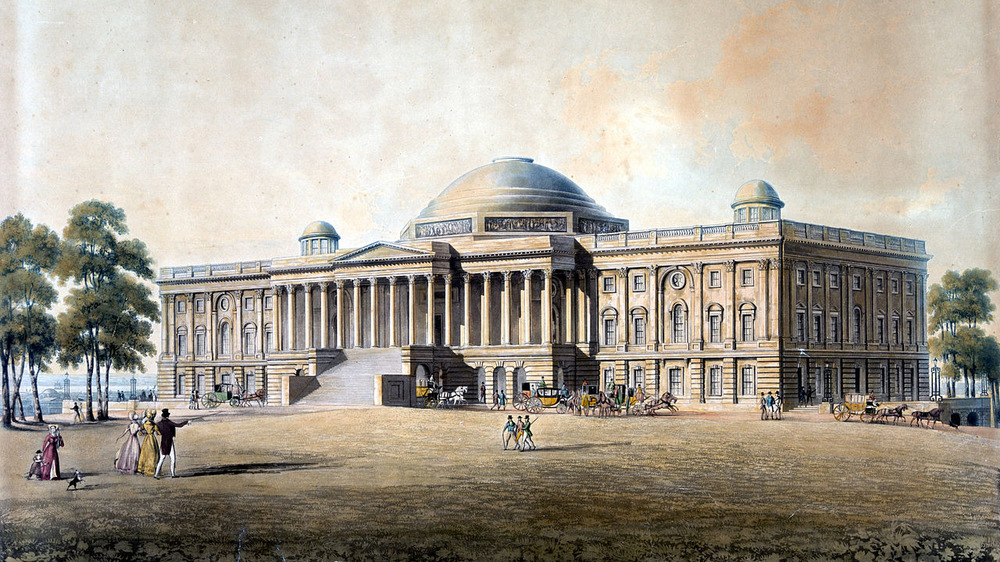

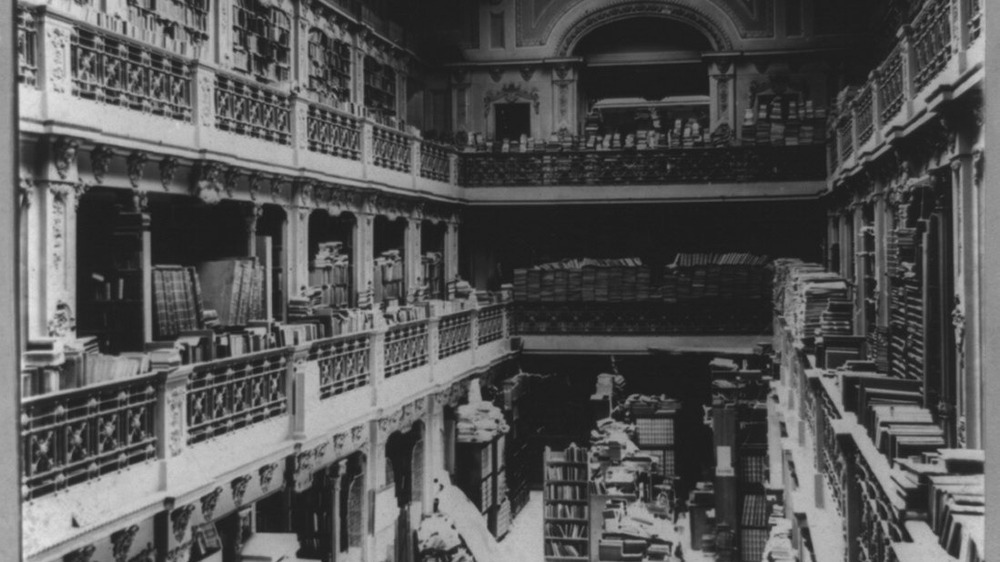

A new Library of Congress was built with fireproof materials

Though conservatism and scant budgets dogged the acquisitions of the Library of Congress, that wasn't necessarily the case when it came to finding a new home for the library. In fact, in 1853, a new Library of Congress building opened, made rather spectacularly out of cast iron. This time, it was hoped, a fire could only get so far in what would eventually become that nation's library.

According to Roll Call, the new metal library was designed in only 18 months by architect of the Capitol Thomas Walter. It was still housed in the Capitol building, now where a number of offices and meeting spaces for the House of Representatives are located.

As absolutely indestructible as an iron library sounds — and it definitely didn't burst into flames over the course of its existence — it didn't last forever. By the 1890s, attitudes had sufficiently changed, along with the acquisitions budget, in such a way that the Library of Congress was growing and needed a separate building. The iron library was disassembled in the summer of 1901 and the metal unceremoniously sold for scrap.

The Library of Congress got into an intellectual arms race with the Smithsonian

Throughout the 1850s and 1860s, the Library of Congress had a rival. During this time period following the devastating 1851 fire, some individuals working with the Smithsonian Institution pushed for their organization to become the nation's library, instead of the Library of Congress. According to the Smithsonian, it made sense, as part of the institution's set-up still includes numerous libraries. Why not just make it a combination national library and museum, a kind of learning utopia for the nation's people?

Yet, there was trouble in the ranks. First Secretary of the Smithsonian Joseph Henry believed that the Smithsonian should essentially concentrate on its scientific mission. Yet, according to The Story Up To Now, Henry was "nursing a viper in his bosom." Said viper was Assistant Secretary in charge of the Smithsonian libraries, Charles Coffin Jewett. Where Henry wanted the Smithsonian to be a research institution, Jewett wanted it to be a library — and he wanted the library to take up most of the Smithsonian's budget.

In 1855, Henry had already fired Jewett, to some controversy. By 1866, Henry was using a pair of fires that hit the Smithsonian to donate the bulk of the Smithsonian libraries to the Library of Congress. The influx of 40,000 volumes set up the Library of Congress to take over as the nation's library, thanks in large part to a professional spat at the Smithsonian.

The fires pushed the Library of Congress to grow, but it took a while

Congress remained conservative with library funding until after the Civil War. Then, a man named Ainsworth Rand Spofford became the Librarian of Congress. He was so instrumental to the growth of the Library of Congress that The Story Up to Now maintains that Spofford "deserves the name of Apostle of the National Library."

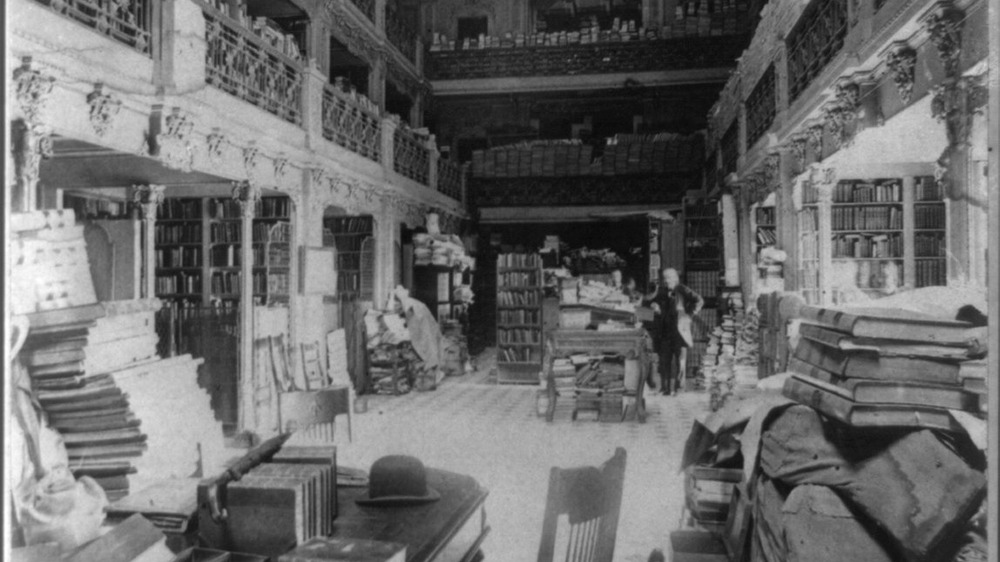

It may sound a bit overblown, but the Library of Congress really does owe much to Spofford. According to the Library of Congress, Spofford was responsible not only for expanding the collections of the library, but also argued for a more independent library and a separate building for the whole shebang. While Spofford clearly had an intellectual mission to make the Library of Congress a national institution, he also had to consider some very real practical affairs. By the 1870s, he realized that the books brought into the collection via copyright laws were starting to swamp him and his staff.

Perhaps, as he saw the books "piled on the floor in all directions," he thought of the 1851 fire. Spofford must have known that the cast iron library he was in would only save the rest of Congress and not necessarily the precious documents under his care. He soon began advocating for a separate building and, in 1896, Congress held hearings about the "condition" of the library. This led to a major expansion and a dedicated library building in 1897.

Today, the Library of Congress isn't skimping on fire safety

Now housed in its own buildings with more modern fire suppression systems, the Library of Congress is certainly better prepared to face a fire than it was in 1851. However, some reports have found issues with the Library's fire safety systems, which are still sometimes hampered by Congressional budgets.

A 2001 report issued by the U.S. Office of Compliance found some pretty concerning problems that left the nation's library vulnerable to yet another blaze. Electrical systems weren't well-maintained, while key fire safety measures like smoke detectors and sprinkler systems were likewise too-often ignored. The supervising engineer of the Library, Frank Tiscione, said that the great majority of the issues could be fixed within two years and well within budget. Yet, more intense structural issues remained a big question, given the complexity of Congressional funding that had to be navigated in order to get things up to code.

Thankfully, things seem to be more up to date in recent times. According to the Architect of the Capitol, the Library of Congress is now outfitted with a plethora of sprinklers, though some carefully designed work makes it tough for visitors to spot the pipes and sprinkler heads right away.