The Untold Truth Of The Origins Of The Yiddish Language

If you've ever called someone a shmuck or a klutz, or just got verklempt on a long-winded spiel where you kvetched about your friend Rudy because he's a putz who schleps his way late to class noshing on a bagel like it's a useless tchotchke or some other piece of dime-store kitsch, yet oy vey, he's still a first-class mensch with a lot of chutzpah, no matter how you'd love to knock the adorable punim on his tuchus, then congrats! You know some Yiddish words (at least how they've come to be used in modern, common parlance).

It's not just New Yorkers and their population of nearly two million Jewish people (per the Jewish Virtual Library), 500,000 of them Orthodox Hasidic (per The New York Times), who know some Yiddish at this point. And Yiddish isn't simply a battery of loanwords that would-be-woke cognoscenti deploy when appearing to sound all worldly, nor is it merely run-off from 1990's Seinfeld dialogue that managed to soak into our collective consciousness.

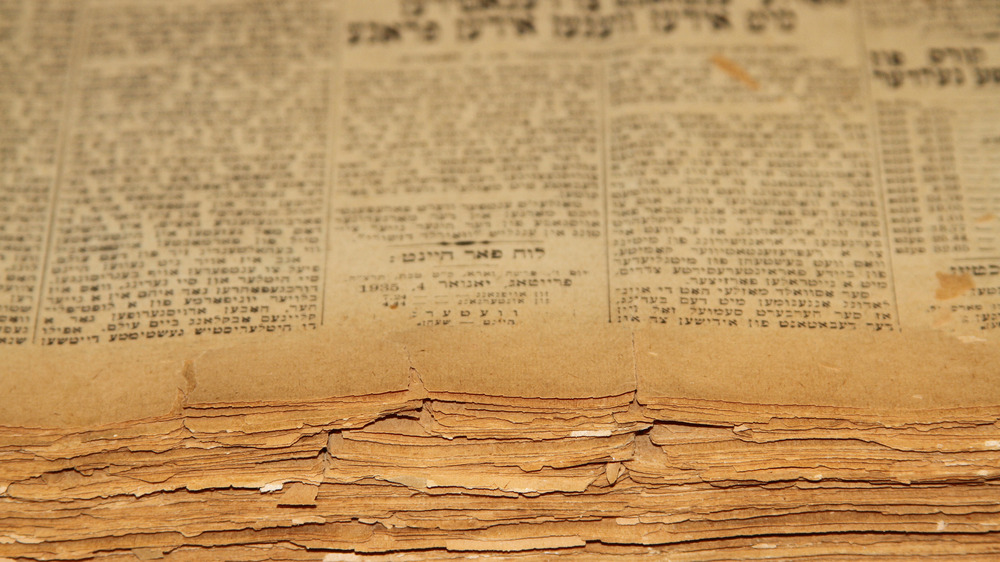

Yiddish is, quite simply, a thousand-year old tongue that is emblematic of the global Jewish diaspora — the scattering of Jewish people away from Israel — that has persisted not only over the language's life, but before its existence. It's representative of the entirety of Jewry as its survived all the while, in all its various forms and orthodoxies. Anyone who is multilingual, or who has had to shift between personas and lexicons in different currents of society will tell you: in many ways, language is culture; language is self.

Birthed from an Ashkenazic Jewish migration from Eastern Europe

The word "Yiddish" is actually the Yiddish word for "Jewish," and came into use only in the 19th century, when European Jewish immigrants made their way to England and the Americas and attempted to pronounce the word to English-speaking ears. And before this? Scholars and ethnographers have argued about the origins of Yiddish for decades.

Near as we can tell, all of the world's Yiddish speakers (per the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, between a half-million and a million people) owe their language to a mere 330 "Ashkenazic" Jews who came from Eastern Europe by way of Turkey (per the LA Times), according to genetic research discussed on Frontiers in Genetics. Two-fifths of all Ashkenazic Jews can be traced back to only two women, per the British Medical Journal. This is doubly confusing because the Biblical term "Ashkenazic" wasn't applied to Jews until the 11th century in Rhineland, southwest Germany. This is why Yiddish is often mistakenly believed to be primarily Germanic.

It's likely that Jewish traders operating from the Roman Empire out to Asia from the 1st to 9th century migrated to modern-day Turkey first, then up to Eastern Europe. This is why, as The Conversation explains, Yiddish sounds like Slavic grammar mixed with German vocabulary — as some have said, "bad German." Yiddish, currently, is a combination of ancient Hebrew mixed with Slavic and German elements, and to make things extra fun, written in Aramaic, a Semitic language from the Middle East.

Scattered by the Crusades and eventually written in Aramaic

Yiddish started to solidify among Jewish immigrants in Germany in the 10th century, and as the Jewish Virtual Library tells us, incorporated local dialects along the Rhine, particularly Laaz, a French derivative. Once the First Crusade was called in 1096 by Pope Urban II, the cohesion of Jewish language made Jews an easy target for discrimination — like a racist today getting upset at an Hispanic person for speaking Spanish. Citizens lashed out at those who were "other." Jewish communities in Speyer, Worms, and Mainz were razed, and Jews in their homes, on the streets, and even in synagogues were slaughtered not by knights, but by Christian peasants, as My Jewish Learning says. This, of course, further drove a wedge between Jew and non-Jew, which accentuated the development of Yiddish.

Jews fled to Eastern Europe over the next several hundred years. They reabsorbed elements of Slavic languages along the way, even while Yiddish remained used within Jewish communities. Poland became a hotspot for Jewish settlers, particularly by the 16th century. It was around this time that Jews began writing Yiddish in Aramaic, the ancient Semitic language of the Middle East, widely spoken since the 8th century BCE, per the Institute of Catalan Studies. This was the language spoken by Jews in Judea around the time of Jesus, ultimately put to paper in medieval Europe to describe a new Jewish tongue in new lands.

The 19th-century Haskalah and resurgence of 'pure' Hebrew

By putting pen to paper, Jewish heritage started to be told through the lens of the Yiddish language. By 1740, as the Jewish Virtual Library explains, Jewish shtetl (communities) in Poland, Lithuania, Germany, Austria, and Russia, especially, sought to secularize and expand their education, inspired by the European Enlightenment that took off about 1685 and lasted until 1815. This period of time, the "Age of Reason," shifted away from dependence on ancient, doctrinal texts for supreme knowledge, and turned to humanity itself for the reason-based, experiential outlook on existence that forms the bedrock of modern science and humanism.

The Jewish Enlightenment, or Haskalah, took off at this time, spurned by secular-leaning Jewish leaders such as Moses Mendelssohn (1729-1786) and Yosef Perl (1773-1839), as described by the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. These leaders, or maskilim, sought to reinterpret the Torah through a non-religious angle, and fought discrimination against Jews through secularization and integration into the same European societies that were denying them rights. The first Haskalah school was created in Berlin in 1778: the Freischule ("Free School"), or Hinnukh Ne'arim ("Youth Education"). It was revolutionary: free, textbook-based, taught literature and numeracy, and accepted women.

As a result, Yiddish was deemed an unclean language of the "dark Middle Ages" that "grates on our ears and distorts," as one maskil said. Hebrew returned as a "pure language." Shedding Yiddish allowed for an easier acceptance of Jews by the countries within which they lived.

Nearly obliterated by the Holocaust

This brings us to one of modern history's most critical junctures: World War II and the Holocaust. As cited by Tablet, Danish linguist Steffen Krogh summarized the relationship between the Yiddish and German languages in the most dramatic, and possibly accurate way: "It's like a young girl who has been raped by her father. This girl can't deny her origins, of course, but she doesn't want to have anything to do with her father."

The Holocaust was the defining, 20th-century marker for not only Jewish people, but their language, Yiddish. Between 1939 and 1946, as Statista calculates, six million of the 17 million murdered by the Nazi regime were Jewish, or two-thirds of the Jewish population in Europe at the time. The population of Yiddish speakers worldwide plummeted (per AP News). Jewish people fled to the soon-to-be-formed Israel (created in 1948), New York, Russia, Canada, elsewhere, and Yiddish became a kind of vernacular, or second tongue, especially for the subsequent generation. Jews living under Stalin in communist U.S.S.R. found no reprieve; it was illegal to speak Yiddish the same as it was illegal to marry a Russian, as The Together Plan explains.

Until then, things had more or less been on the up-and-up for Yiddish-speaking Jews, barring conflicts due to doctrine. Ultra-orthodox movements like Hasidism had arisen in Poland in the mid-1700s, partially in response to the Haskalah, per PBS, but they would ironically play a large part in keeping Yiddish alive and relevant.

On the rise among Haredim, Hasids, and popular culture

At present, Yiddish is largely spoken in communities that have either remained untouched through centuries of warfare and persecution, such as villages in Moldova, Romania, Hungary, and Ukraine, as Tablet says, or by orthodox offshoots such as Haredim in Israel or Hasids in New York.

Satmar Hasidic Jews, for instance — centered around Borough Park in Williamsburg, Brooklyn — attend Jewish schools, typically stay within family businesses, and never marry non-Jews. They don't consider themselves "ultra-orthodox," as Chabad states; they just believe they're doing the right thing to keep their heritage intact. And of course, Hasids (and other Jews, of course, primarily in New York) brought to us all those colorful Yiddish words like "shmuck" and "putz."

In fact, as The Economist outlines, Yiddish literature and music are entering a kind of near Renaissance. With a bit of helpful historical hindsight, scholars are starting to view Yiddish as a "real" language, as the Jewish Virtual Library says, not a "corrupted tongue." Universities — even those as prestigious as Oxford — are offering entire research degrees in Yiddish studies, as listed on the Oxford website. Pop culture dramas such as Netflix's Unorthodox have gotten into the mix, portraying the relevance and power of Yiddish as it relates to Jewish identity, history, and culture.

In Israel, which encompasses the ancient Roman province of Judea, Hebrew is the official state language, as Alpha Omega Translations says. Yiddish, though, is still commonly spoken.