Extinct Animals Science Wants To Bring Back

Ever since "Jurassic Park," people have been talking about bringing extinct animals back from the grave. While it isn't possible to revive animals that died out hundreds of millions of years ago, it may be possible to bring an animal out of extinction if it died out less than 800,000 years ago. Here are some of the more interesting animals we may finally be able to see in the flesh for the first time.

Woolly mammoth

It's too bad modern humans will never get to see a real woolly mammoth ... or, will they? That's the plan behind a company called Colossal, which received $15 million in private funds to continue working on bringing the woolly mammoth back to life. According to The New York Times, the company's head, Harvard Medical School biologist George Church, had been working on the project on a small scale for nearly a decade when they were awarded the massive amount of funding.

The idea is that they're going to be taking elephant DNA, and mucking about with individual genes to add, subtract, and tweak elements that will give these new creatures the traits of the woolly mammoth — like their heavy fur coats, fat stores, and ability to thrive in extreme cold.

There's actually reasoning behind this, aside from "Look what we can do!" CNN spoke with Love Dalen, a professor of evolutionary genetics at the Centre for Palaeogenetics in Stockholm. Dalen says the work has merit — particularly in re-establishing genetic diversity in endangered species — but there's a catch. The genetically engineered creatures aren't technically mammoths but are, instead, "hairy elephants," so the hopes of releasing them into the Arctic and rebalancing the ecosystem is ... iffy. There's a theory their reintroduction might help stabilize the area's permafrost, but the evidence is lacking. There are also the ethical concerns of putting the lives of elephants at risk to make them act as incubators for the baby almost-mammoths, and bottom line? It's complicated.

Cave lions

Cave lions were massive predators that roamed Europe and Asia until about 10,000 to 12,000 years ago. Bigger than today's lions, they weighed up to 800 pounds when grown, and according to ThoughtCo., they counted cave bears among their prey. It's not clear just why they went extinct, but the discovery of a handful of eerily well-preserved individuals has got scientists wondering about whether or not they can take the pieces and put these apex predators back together again.

Most recently found were two-month-old cubs researchers have named Boris and Sparta. The pair were recovered from the same place — near the River Senyalyakh in eastern Russia — but lived around 15,000 years apart. The younger — and more physically intact — cave lion cub is Sparta, who would have been toddling around her cave, chasing her mom's tail just under 28,000 years ago (via NBC). Until, that is, mom left and never returned — according to The Siberian Times, Sparta died in an "extreme stage of starvation."

The young cave lions were so intact that there were almost immediately questions about using them to bring their entire species back, said the BBC. It was an endeavor that Dr. Albert Protopopov suggested would be even easier than bringing back a mammoth. "Cave and modern lions separated only 300,000 years ago," he explained. "In other words, they are different species of the same genus ... It would be a revolution and a payback by humans who helped extinguishing [sic] of so many species."

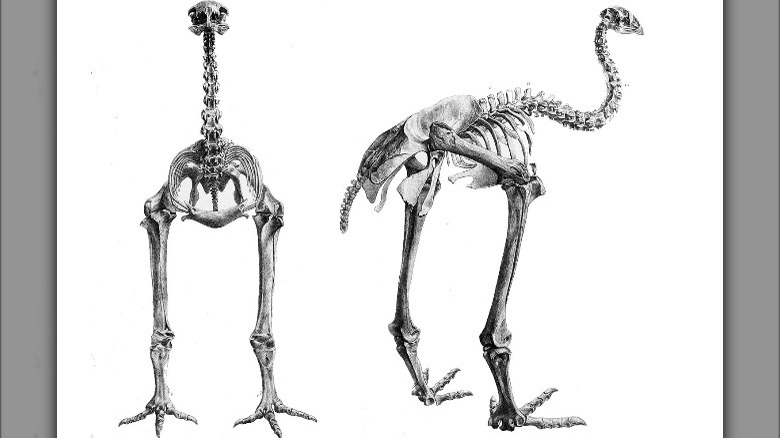

Moa

New Zealand Birds Online describes the moa as a group of giant, flightless birds that — once plentiful — were driven to extinction thanks to overhunting from humans. The little bush moa (skeleton pictured) was one of nine different species, and it made headlines in 2018. That's when researchers from Harvard University completed the first step in "de-extinction": the completion of a full genome, using DNA taken from the toe bone of a little bush moa that had his (or her) final resting place in a not-so-peaceful museum.

It was no small feat, according to Stat News. DNA starts decaying from the time of death, and it was described sort of like taking a shattered glass and trying to piece it back together — only in this case, the research team was dealing with 900 million nucleotides (the base building blocks of DNA), and millions of DNA fragments — which then needed to be pieced together to build the genome.

Skeptics, however, have cautioned about the practicality of this for a number of reasons (via the New Zealand Herald). Not only would there have to be a large number of individuals created and cloned to allow a wild population to support itself without inbreeding and collapse, but the environment has changed in the 600 years since extinction. The result could be an animal "inherently maladapted" to the modern world. Meanwhile, others — like IdeaLog — suggest the funds would be better spent protecting the endangered animals that are still around, like the kiwi.

Pinta Island Galapagos Tortoise/Floreana tortoise

The island of Pinta in the Galapagos Islands was — like many things — ruined by people. In 1959, fishermen put three goats on the island, thinking they'd made a few more baby goats, and it would be a handy meat supply. Unfortunately for everything already on the islands, the goats made a ton of goats — around 40,000 of them by 1970 — destroyed the ecosystem.

According to the Galapagos Conservancy, the tortoise that would become known as Lonesome George (pictured) was moved to the island's tortoise sanctuary, but after repeated attempts to find him a suitable mate failed, he died in 2012. It was believed he was the last of his kind, but now, science has good news.

In 2020, NBC reported that conservationists had found a female relative of Lonesome George's. She's a direct descendent of the same species, and after she was discovered, the team also found 18 other females and 11 males who were basically hybrids of two species: the Pinta Island tortoise (like Lonesome George), and the extinct Floreana Island tortoise. It's also believed there are more such hybrids, carrying the DNA of their extinct ancestors. Will it be enough? Reptiles Magazine says that the newly discovered genomes — including that of the female who shared 16% of her genes with Lonesome George — will hopefully be enough that conservationists will be able to kick off a selective breeding program to resurrect the Pinta and Floreana tortoises. And good news: Their homes are now goat-free.

Dinosaurs

There have been plenty of cautionary tales told about the dangers of messing with dinosaur DNA, but that hasn't stopped real-life scientists from giving it a go. And the results? They've been ... interesting and disturbing at the same time. In 2016, researchers from the University of Chile decided to muck about with the DNA of perfectly ordinary, perfectly innocent chickens. According to Science Alert, they didn't need dinosaur DNA to reverse-engineer modern chickens into something more like their ancient ancestors, and by basically turning off a gene called IHH, it prevented the gene from halting the growth of the fibula. With that gene turned off, chickens grew bones that looked disturbingly like the bones of the ancient Archaeopteryx.

The Smithsonian said that something similar had been done a year prior, when paleontologists at the University of Chicago led a study to tweak chicken DNA to give embryos snouts instead of the standard beak. They were just trying to find out how beaks evolved in the first place, but with further advances, they just might have the tools to go one step further.

In 2020, National Geographic reported on findings that came out of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in China. Researchers had found what looked like dino DNA in the remains of a 75-million-year-old skull, and more dino DNA — this time from 120-million-year-old fossils — was (possibly) found in 2021. While researchers say (via LiveScience) that they're far away from rebuilding an entire dinosaur, this could be the first step.

Aurochs

Humankind's awe of a particular animal has rarely been as well-recorded as the awe felt of the aurochs. According to Mihnea Tanasescu of Vrije Universiteit Brussel (via The Conversation), the ancient cattle weren't just the subject of countless prehistoric cave paintings, but they also got a shout-out in the writings of Julius Caesar, who called them "extraordinary." Like so many species, they were a casualty of human activity: Hunting, domestication, and the habitat loss that came with the spread of agriculture meant the end of these magnificent, primordial oxen, with the last wild one dying in 1627.

That may change, in a pretty amazing way. Conservationists concerned about the future of a wild Europe have proposed a massive rewilding scheme, and rebuilding aurochs — then reintroducing them to the wild — is part of that. The idea is pretty straightforward: Aurochs disappeared in part because they bred with domesticated cattle, and some of their genetic material and traits live on in modern cattle. By selectively breeding for those traits, it's hoped that an entire species of aurochs will be distilled out of those cattle.

How's it going? Pretty good, actually. In 2021, DW reported on a calf that had been born in March of 2020. His name was — appropriately — Darwin, and simply put, he's amazing. He marks the so-called Generation F3, which will be the parent generation of offspring that researchers hope to call "very, very close" to their ancient ancestors.

Thylacine

The thylacine — or Tasmanian Tiger — is definitely extinct, says The New York Times. Still, that hasn't stopped the buzz about it, and in recent years, there have been more reported sightings of the Thylacine than of Bigfoot and Elvis combined. That's given rise to a fascinating conversation about perception and interpretation of things like photographic "evidence," but just as interesting is the fact that someday, people might be seeing actual, living thylacines again.

This weird sort of marsupial dog only went extinct fairly recently: According to National Geographic, the extinct designation was only made official in 1982, the last captive animal died in 1936, and it's believed the last wild ones died in the 1940s. Examining DNA from a 108-year old baby thylacine was meant to be an experiment that would hopefully determine how wolf-like they were, and in 2008, that escalated into taking that DNA, injecting it into a mouse, and seeing it actually function to guide bone and cartilage development.

Then, it escalated quickly. In 2010, the preserved remains of a thylacine joey yielded enough DNA that researchers from the University of Melbourne called it (via Cosmos) "the roadmap for getting a thylacine back." The idea has then become to rebuild the thylacine genome, gestate it in a surrogate or an artificial womb, and see what pops out. Project leader Andrew Pask says that while there's some big hurdles in the way, "you never know how fast some of these technologies will develop."

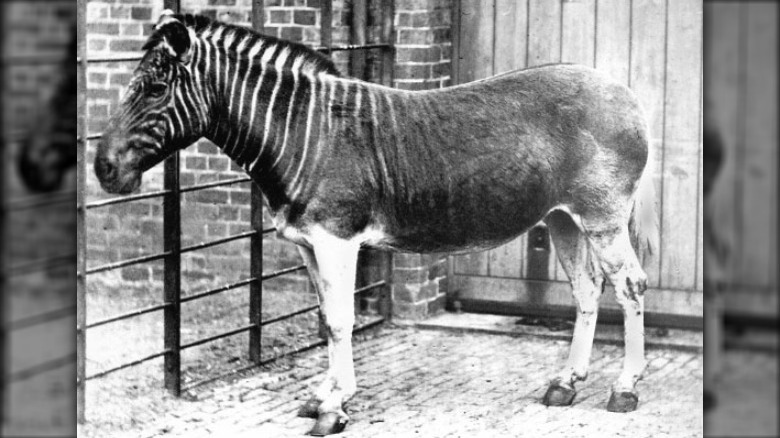

Quaggas

Way back in ye olde times, the term "Quagga" was used to refer to any zebra that had a specific and distinctive pattern of stripes. The Quagga Project says that helped lead to the very mistaken belief that there were many more of the animals than there actually were, and they were hunted into extinction. The last Quagga died in an Amsterdam zoo in 1883, and since then, DNA analysis has proven that they were a separate subspecies of the Plains Zebra... and not just a zebra baby born to a mom who had run out of printer ink. Oops.

Fast forward to the late 1980s, and the start of an ambitious breeding project. The idea was to take closely related zebras selected for their Quagga-like traits — like brown coats and a lack of stripes — and breed them in such a way that the traits would be accentuated in the next generation. Reinhold Rau's pioneering work on the project was initially met with pretty wild disdain, but he didn't listen.

The project's first foal was born in 1988, and these faux-Quaggas are now named Rau Quaggas. Updates to their social media show that as of 2021, they were welcoming their next generations of foals. Entire breeding herds led by hand-selected stallions are currently producing their 6th generation, which The Quagga Project says is getting closer and closer to the original animal.

Passenger Pigeon

According to Trent University's Eric Guiry (via The Conversation), passenger pigeons went from numbering in the billions — flying in flocks so large that they were once called a "biological storm" — to gone in just around 40 years. The last died in 1914, and it was the end of a species that was found to have been completely decimated by wanton, large-scale slaughter.

Now, however, an organization called Revive & Restore is working on bringing them back. The idea is to take a flock of rock pigeons that have been engineered to include something called a Cas9 gene. Without getting too sciency, that's the gene that allows for the use of a gene editing tool called Crispr, which scientists plan on using to add DNA from the extinct passenger pigeons to new generations of rock pigeons.

In 2019, the program saw the birth of its first pigeon that contained the Cas9 gene. His name was Apsu, and while they also found that it was highly unlikely he would pass the gene on to his offspring, it was a start — and they were still hoping for the first new passenger pigeons to hatch in 2025. Not everyone is thrilled, though, with some ornithologists — like David E. Blockstein of the National Council for Science and the Environment — claiming that it's not just unethical to de-extinct the pigeons, but it could be devastating to an environment that's no longer used to having them around.

Great Auk

The story of the Great Auk is a pretty harsh one, and it ends with extinction. This large, flightless bird was once plentiful, but as exploration allowed humankind to expand farther and farther into the birds' territories, they became easy pickins. By the 16th century it was clear that something needed to be done, and warnings not to hunt the birds just made the demand for their feathers and corpses increase, and did the exact opposite of good. The last ones were killed in 1844, but according to The Telegraph, they might be due for a return.

The research institute Revive & Restore outlined a plan in 2016, and it involved tracking down preserved remains of Great Auks, finding and extracting DNA, then using that to rebuild the birds' genome. That, then, would be inserted into the embryos of a razorbill — the Great Auk's nearest living relative — which would then be implanted into another bird. That bird would have to be big enough to carry and lay a Great Auk egg, which is why the razorbill doesn't fit the, well, bill.

Could it work? Like most attempts at resurrecting an extinct species, the answer is, "Maybe?" The good news is that they had the perfect place to test the theory — once the birds hatch — and that was the already bird-centric Farnes islands, off Britain's east coast.

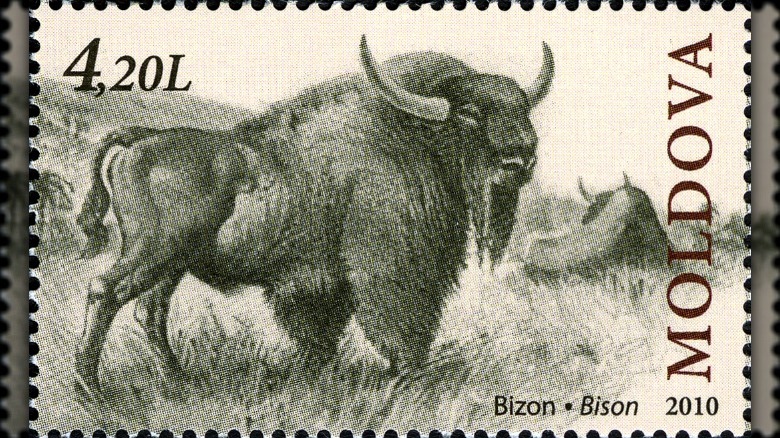

Steppe bison

The ancient steppe bison was a pretty big deal: According to the Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre, these were not only one of the few megafauna to survive through the last Ice Age, but when they spread from their native lands in Asia, they crossed the land bridge into North America and gave rise to America's famous bison. They went extinct sometime during the Holocene period, but according to the International Business Times, they might once again be thundering across the steppe ... if science has anything to do with it, that is.

In 2016, an ancient but well-preserved steppe bison tail was discovered in the permafrost around the Indigirka river basin. Researchers from the North-Eastern Federal University date the tail to around 8,000 years ago and are pretty sure it's intact enough that it'll yield some DNA.

That DNA, they say, would then be used to create clone embryos of the steppe bison, which could — in theory — be implanted into a cow. They estimate the baby born to the surrogate mother would be "99.8% newborn bison," but that's a bit down the road. Before trying it with a steppe bison, scientists said they first needed to learn how the process worked and if it was even viable. That meant testing it first, and the successful cloning of a Canadian wood bison would have to be done before attempts were made at bringing back the steppe bison.

Heath hen

It's nowhere near as flashy as, say, a woolly mammoth, but it turns out that the restoration of the heath hen might be much more practical — and possible. The conservation and de-extinction organization Revive & Restore is working on the heath hen project, and they say it's notable as one of the first species that Americans actively tried to protect. Once widespread across the northern Atlantic coast, residents of Martha's Vineyard established a preserve for the only birds remaining in 1870. All their efforts were ultimately in vain, and the heath hen vanished in 1932.

They're currently working on a few aspects of the de-extinction, and that includes figuring out where the heath hen fits in with living relatives on a genetic level. They're also trying to figure out what behavioral and biological traits made them different from other birds, what genetic pathways those things are connected to, and how to tweak embryos to produce these decades-dead birds.

There's good news, at least. The preserve established on Martha's Vineyard remains a viable location for reintroducing the birds, and they thrived there. Numbers had been on the rise until wildfire destroyed all but 50 birds, meaning that once the birds hatch, they'll have a place to go.

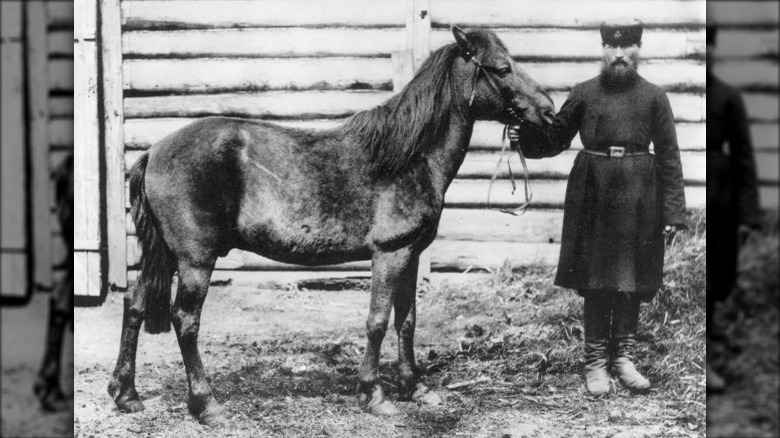

Tarpan

Tarpans were once the wild horses of Middle Europe and Asia: Hardy and strong, their story ends with, of course, extinction. But here's the thing — according to the World Wildlife Fund, some of the last remaining tarpans weren't killed, they were caught and cross-bred with the domesticated workhorses of early 19th century Poland. (Rewilding Europe notes, however, that the last known wild mare was killed during attempts to catch her.) That created an entirely different breed that was the best of both worlds, and it was called the Konik Polski.

Not that many generations had passed when, in 1936, breeders started choosing Konik horses that had traits more like the ancient tarpans than their workhorse ancestors. By 2005, there were 2,500 almost-tarpans living in a reserve in Latvia.

There's a huge "but" here, and that's the fact that they're not really true tarpans. According to the True Nature Foundation, there are actually other horse breeds — like the Exmoor pony, the Fjord horse, and a handful of breeds from Spain that are genetically closer to Europe's original wild horses than what the Konik is. Should those looking to bring back the tarpan look elsewhere?

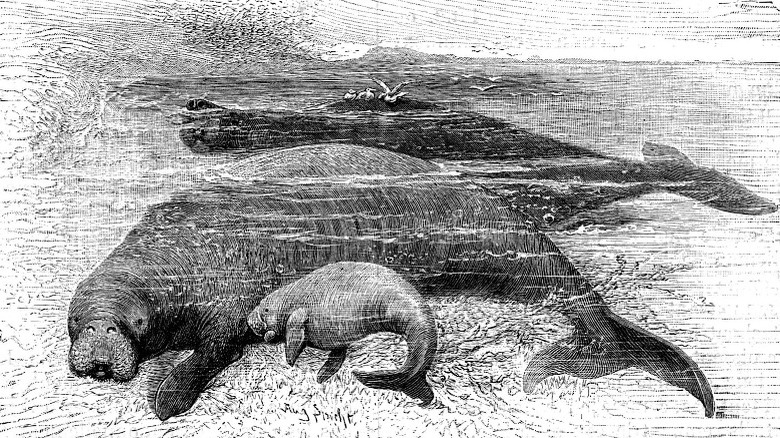

Steller's Sea Cow

The Smithsonian says that when Georg Wilhelm Steller saw and documented the existence of what would become the Steller's sea cow, it was almost extinct already — and it would last just a few more decades before it went absolutely extinct in 1768 (via Revive & Restore). Hunting played a big part in it, but when Sci-News reported that researchers from Norway's Nord University had managed to sequence the genome of a sea cow, they found that a long period of climate change had resulted in the species' slow decline.

Today, Revive & Restore is looking at the sea cow as a potential candidate for de-extinction. The hope is that bringing back the sea cow — and some other key species — will help stabilize an ecosystem and repair some of the damage done by extinction, and by other factors.

It's a massive undertaking, and while the 2021 sequencing of the sea cow genome means that one hurdle has been overcome, there are still other things to consider. The ecosystems have changed in the last few hundreds of years, so making sure there's still a place for the sea cow is paramount — along with also making sure that the factors that led to their extinction in the first place are no longer an issue.

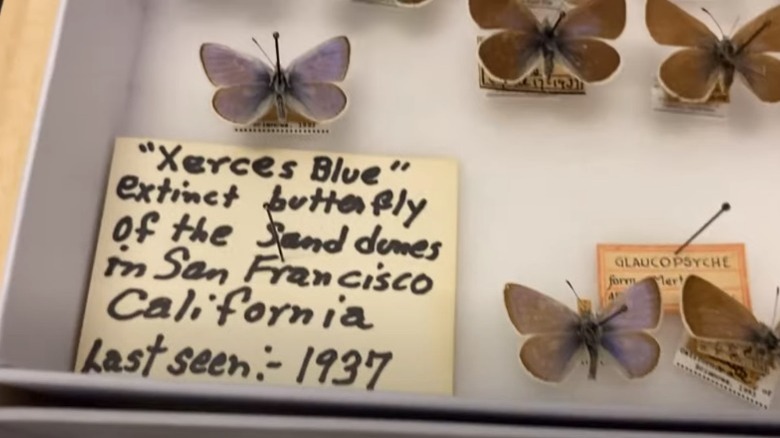

Xerces blue butterfly

The Xerces blue butterfly is an example of a creature that's small yet mighty — even though it truly didn't become powerful until it vanished. According to WTTW PBS, the butterfly was the first species that scientists were able to prove went extinct solely due to human interference. In this case, it was habitat loss: As populations grew out from the San Francisco area, the landscape was changed, field and sand dunes were turned to pavement, and native flowers disappeared.

The Xerces blue butterfly became a symbol of the damage humankind has done, and in 2021, Science News says that conservationists got the news they were looking for. DNA extracted from a 93-year-old specimen from Chicago's Field Museum proved that not only were people to blame but that the butterfly was, in fact, a separate species and not a subgroup as some had argued.

The butterfly's status as an icon for conservation has also gotten it attention as a candidate for de-extinction, thanks to recent developments in the field. In addition to mucking about with DNA, there's another theory, too: Some scientists believe that thanks to a habitat restoration project, introducing a closely-related butterfly might kick-start a re-evolution of the Xerces. Still, Felix Grewe, Xerces researcher and co-director of the Grainger Bioinformatics Center, summed up everything that needed to go before de-extinction: "Before we start putting a lot of effort into resurrection, let's put that effort into protecting what there and learn from our past mistakes."

Carolina parakeet

The beautiful Carolina parakeet was the only parrot indigenous to the United States. At one time, the parakeet was prevalent all across the North American continent, but it was declared extinct in 1939. It had an obnoxiously loud call and would eat the seeds and crops of farmers, so basically they were killed off due to being annoying. Oh, and it was likely poisonous, due to its regular diet of cocklebur seeds. But it sure was pretty, so let's bring it back.

Efforts to revive this extinct animal have followed similar plans to breed dormant genes into similar extant species. The closest known relative is the Jandaya parakeet, from the eastern South American rainforests. Cross-breeding programs, as well as attempts to isolate the extinct genetic code and introduce it into a Jandaya embryo are underway — if successful, the Carolina parakeet will likely settle on the shores of Lake Okeechobee in Florida. Researchers plan to introduce 100 birds there, once they've succeeded in breeding them in captivity — assuming their annoying squawks don't quickly result in extinction part two.

Southern gastric-brooding frog

The Southern gastric-brooding frog went extinct sometime in the mid-1980s, and scientists want to bring it back, if for nothing else than pure amusement. See, the gastric-brooding frog didn't pick its name out of a hat — it was called that because it literally gave birth from the mouth. Eggs would be laid into the mouth, and travel into the stomach. The stomach would then turn into a uterus, where the eggs would incubate. When they hatched into tadpoles, they would remain in the stomach/uterus until they matured into tiny frogs, at which point they would birth themselves from mama's mouth. These were the only organisms ever known to reproduce this way, and ... we wanna see it.

In 2013, researchers funded by the Lazarus Project succeeded in growing embryos containing the revived DNA from the gastric-brooding frog. They accomplished this by inserting the dead material from the extinct frog, into donor eggs from a living species. The eggs continued to grow into embryos, the first time such a technique was achieved for an extinct species. Continued analysis proved that the cells from the extinct frog were multiplying, which allows for the potential for us to one day gawk at a frog that literally hiccups babies from its mouth.

Pyrenean ibex

The Pyrenean Ibex, also called the bucardo, is certainly a contender for de-extinction ... mainly because we already did it! Kind of.

Bucardos, a type of Spanish goat that lived in the Pyrenees mountains that border France and Spain, was on the verge of extinction in 2000, with only three females still alive. Once they died out, French and Spanish scientists harvested as much of their genetic information as they could and started a project to clone the animal. They succeeded in manipulating the DNA of a bucardo and placing it into the embryo of a surrogate mother, a common goat. A baby was born on July 30, 2004, but died of respiratory issues minutes later.

Not only was this a significant achievement in cloning technology, but it represented the first successful live birth of an extinct animal. Though the baby died, the experiment proved that de-extinction was possible.

A new effort to return the Bucardo from extinction began in 2013 by the Centre for Research and Food Technology of Aragon (CITA). One of the principal scientists behind the effort, Dr. Alberto Fernandez-Arias, began the process of determining if the 14-year-old genetic information obtained from the last living bucardo is still viable. The sample has been frozen in liquid nitrogen since it was last used, so part of the project isn't just to bring back the bucardo, but also to see if preserved material can be used after an extended period of time. If everything checks out, they'll attempt the cloning and breeding process all over again, and hopefully get more than a few minutes' worth of success this time.