The Untold Truth Of Orson Welles

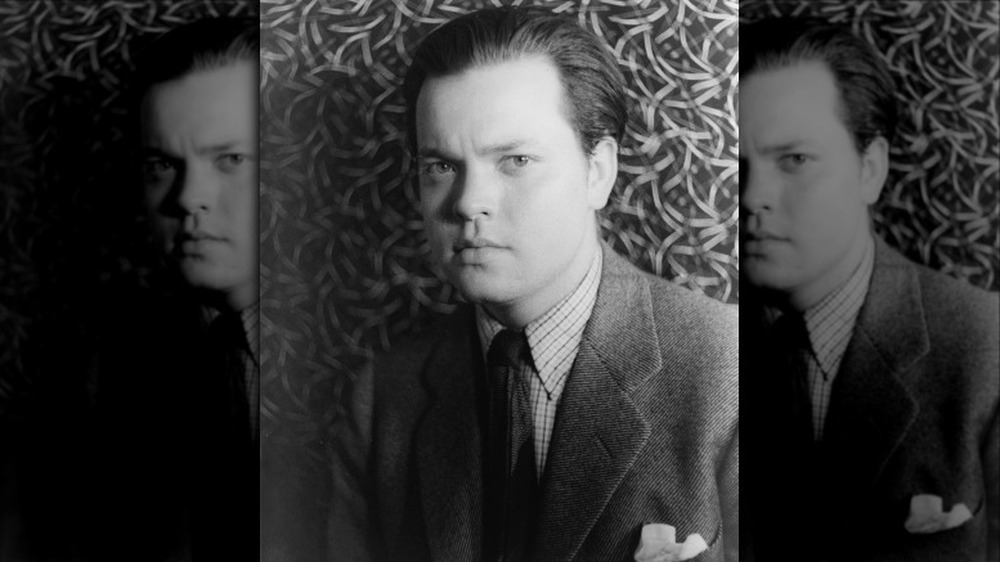

The life of Orson Welles was a morass of often tragic contradictions. A child prodigy with an affinity for the arts and literature, Welles conquered the stage and broadcasting as a young man. A pioneer of radio drama, Welles courted controversy and shocked the nation with his broadcast of the Mercury Theatre's adaptation of War of the Worlds in 1938. Welles, however, found his true voice in film. His debut feature, 1941's Citizen Kane, would be hailed as the greatest film of all time. At age 25, Welles was arguably America's greatest cinematic innovator, but his penchant for excess and refusal to yield to the constraints of the studio system would prematurely stifle his promise.

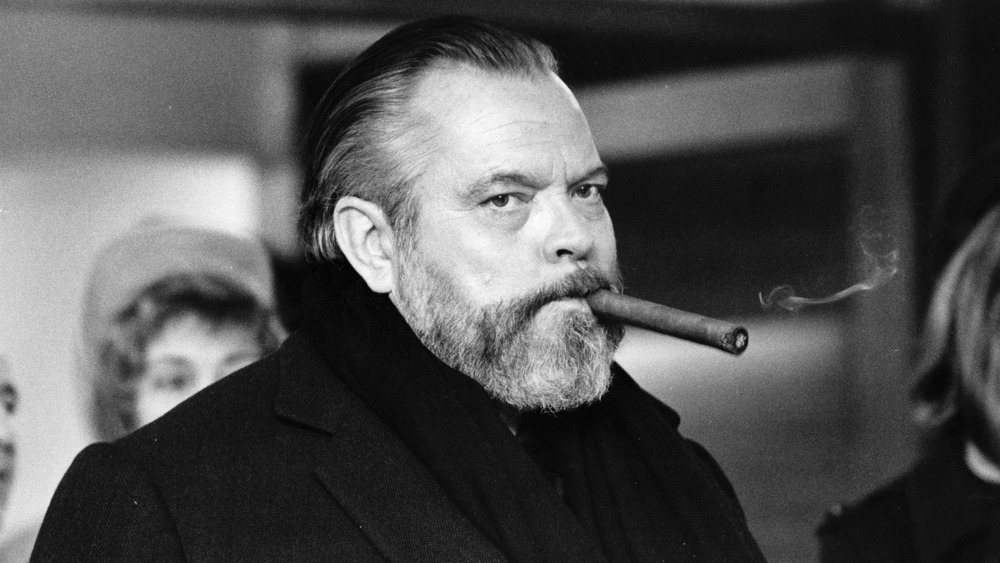

Welles spent decades fighting for the total creative control he was afforded on Citizen Kane only to be repeatedly hobbled by the studios. With his vision blunted by censors and studio executives, Welles struck out on his own as an independent filmmaker, raising funds through acting jobs in projects that were frequently beneath his considerable talents. Although critics and film scholars championed his genius for the entirety of his career, by the end of his life he was regarded mostly as a television pitchman by the general public. Just months before his death, Welles lent his trademark baritone to the toy-based 1986 animated feature, Transformers: The Movie, as the voice of the villain Unicron — an ignoble end for the man who directed Citizen Kane. From triumph to tragedy, this is the untold truth of Orson Welles.

Orson Welles' childhood was filled with privilege and tragedy

George Orson Welles was born on May 6, 1915, in Kenosha, Wisc. As documented by Barbara Leaming, author of Orson Welles, a Biography, Welles' father, Richard Head Welles, made a small fortune as the inventor of a popular carbide lamp used on automobiles and bicycles. When the industry shifted from carbide to electrical lamps, the elder Welles sold his manufacturing firm to concentrate on other inventions with varied success. Welles' mother, Beatrice Ives Welles, came from an affluent family and was an accomplished pianist with an interest in intellectual pursuits. She was also an early advocate of women's rights.

Although an adult Orson Welles would remember his parents as "mythically wonderful," his family was not without its troubles. The ever practical Dick Welles often found himself at odds with his wife's artistic interests. Beatrice Welles took issue with her husband's freewheeling love of music halls and showgirls. When a doctor named Maurice Bernstein took an interest in young Orson, declaring the child a genius and lavishing attention on Beatrice, Dick turned to alcohol. When Orson was 6, his parents separated. Nevertheless, Orson thrived as a gifted child and a talented, if not reluctant, violinist and pianist.

Just a few years later, Beatrice died of jaundice. Orson would then accompany his hard-drinking father on aimless travels around the globe. Like his wife, Dick Welles died young. At 13, Orson found himself in the care of Bernstein, who would continue to nurture him as a prodigy.

Orson Welles found a lifelong direction at 11

His mother's status as a celebrated concert pianist brought young Orson Welles into contact with the foremost musicians, intellectuals, and scholars of the day. Welles' father, on the other hand, introduced him to the seamier side of life, exposing him to cartoonists, sportswriters, and a host of Runyonesque characters. Rarely exposed to children his own age, Welles developed relatively sophisticated tastes early in life. Save for a disastrous attempt at enrolling in public school for the fourth grade, Welles was educated at home by Beatrice Welles, who began reading the works of Shakespeare, Keats, and Tennyson to him at age 2, writes Frank Brady.

At 11, Maurice Bernstein and Dick Welles enrolled Orson at the Todd School in Woodstock, Ill. As detailed in Orson Welles, A Biography, neither Orson nor the Todd School were particularly excited about the young prodigy's enrollment. Orson recalled to biographer Barbara Leaming that he "left in the spirit of one sent to the slammer." Orson's older brother, Richard, had been expelled from the school a decade earlier for disciplinary problems and Todd's headmaster, Noble Hill, didn't relish contending with another Welles child.

Nevertheless, Orson thrived under the tutelage of an instructor named Roger Hill. Hill recognized Orson's budding genius, ascertaining that his pupil had an IQ of 185, and fostered within him a love of theater, encouraging him to concentrate on subjects that interested him. With Hill as his mentor, Orson used his five years at Todd to hone his mastery of the arts, literature, and drama.

Orson Welles toured Ireland at 16

Although Orson Welles' first creative outlet was music, and his first real success was in theater, painting was his true love. After graduating from the Todd School at 16, Welles took a modest inheritance bequeathed to him upon his father's death and journeyed to Ireland where he toured the countryside as an itinerant artist.

In Peter Bogdanovich's This is Orson Welles, the Citizen Kane director explained his early artistic evolution and how painting brought him to Ireland. "I started in music—as a sort of imitation musical Wunderkind," Welles told Bogdanovich. "That had to do with my mother, who was a most gifted pianist. I've never played a note since she died. I was nine when that happened, and already I'd started to paint. That's what I've loved the most. Always. . . Anyway, that's how I happened to be in Ireland. I'd been traveling around with a donkey and cart and a big box of paints all summer."

However, Welles' Bohemian existence on the Emerald Isle was fraught with poverty. Although Welles had a scholarship to Harvard pending his return to the states, he dreaded the idea of returning to school. As detailed in Orson Welles, A Biography, Welles' plans of doing some serious painting had resulted in his composing just six works that he referred to as "hideous abortions" that he had traded for lodging. With summer ending, Welles set his brush and palette aside and turned to his gifts as an actor to earn money.

Orson Welles' early career in theater

According to biographer Barbara Leaming, Orson Welles was far more successful at carousing and partying than painting during his artistic sojourn to Ireland. With his funds running low, Welles was in real danger of becoming destitute in a foreign country.

Striking out for Dublin, the home of the illustrious Abbey and Gate theaters, Welles set his sights on the stage. However, it wasn't Welles' talent or confidence that would land him his first role. While attending a performance of The Melians at the Gate, he spotted an acquaintance on stage in a small role. Invited backstage by his friend, Welles struck up a conversation with the theater's co-director, Hilton Edwards. In grand style, Welles explained to Edwards that he was a visiting actor from New York who had just completed a successful run of performances with the Theatre Guild.

Welles' tall tale was ultimately unnecessary. He turned out to be a superlative actor and exactly the type Edwards needed for a particularly difficult-to-fill role in an upcoming production. After a perfunctory audition, Welles was added to the Gate's company. Virtually overnight, Welles went from being a down-on-his-luck, would-be painter to a professional actor with one of Europe's most prestigious theaters.

Despite a successful run as Karl Alexander in the Gate's production of Jew Süss, Welles was largely relegated to smaller roles — likely because of jealousy on the part of Edwards' professional and romantic partner Michael MacLiammoir, who felt upstaged by the young actor.

Orson Welles was a radio wunderkind

After appearing in several plays, Orson Welles left Ireland for New York. At 19, Welles made his Broadway debut as Tybalt in Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, where he caught the eye of a young theater producer named John Houseman. Houseman cast Welles as the lead in the play Panic, beginning a successful and tumultuous professional partnership.

In 1936, Houseman, while working with the Federal Theatre Project, a New Deal program designed to get actors working again after the Great Depression, hired Welles to direct Macbeth. Featuring a cast of Black actors, Welles transposed the action from Scotland to Haiti, marking the first of many of the director's revolutionary treatments of Shakespeare's material.

Following a staging of the controversial The Cradle Will Rock, Houseman and Welles left the Federal Theatre Project to form their own repertory company. Dedicated to innovative, modern drama, the Mercury Theatre would find acclaim for their revolutionary stage and radio productions.

As detailed in a 2013 PBS documentary, Welles and the Mercury Theatre would become legendary in radio history for their 1938 Halloween broadcast of War of the Worlds. Directed and narrated by the 23-year-old Welles, the broadcast caused a minor panic when some listeners assumed the production, partly dramatized in the style of a news bulletin, was an account of an actual extraterrestrial invasion. Although the scope of the panic was largely inflated by the press, some officials called for greater regulation of radio broadcasting. Nevertheless, the program established Welles as a master storyteller.

The trials of Citizen Kane

As detailed in The Making of Citizen Kane, by Robert L. Carringer, Orson Welles' 1939 entry into filmmaking came with an unprecedented degree of freedom thanks to RKO Studios' head George L. Schaefer. Luring Welles away from radio with a contract that offered an incredible degree of creative control, Schaefer was confident that the untried director would deliver. In addition to writing, producing, directing, and acting in the film, Welles was also given the right of final cut — an unheard of proposition in the 1930s and rare for even the most experienced directors today. Initially, the contract would make Schaefer and his "boy wonder" laughingstocks in the film community.

Based loosely on the life of newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, Citizen Kane stars Welles as Charles Foster Kane, a newspaper tycoon who rises from obscurity to become one of the most powerful men in the world only to find himself alienated by his hubris and pining for his lost youth.

Although the film would prove a critical hit, Citizen Kane faced an uphill battle to its release. As documented in Pauline Kael's Raising Kane, MGM's Louis B. Mayer, fearing Hearst would take his wrath out on the film industry, offered Schaefer $842,000 to destroy the film. Hearst's attacks on the film ultimately damaged its box office receipts. Citizen Kane languished as a curiosity until its subsequent revival as an arthouse film in the 1950s, when film scholars would reevaluate Citizen Kane as arguably the greatest film ever made.

The many loves of Orson Welles

As detailed in Barbara Leaming's 1985 biography, Orson Welles married Virginia Nicolson, an 18-year-old student enrolled in Welles' theater festival at the Todd School, in 1934. Nicolson stayed with Welles throughout his early stage and radio career. The couple divorced in 1940 just before Welles began work on Citizen Kane, due largely to Welles' affairs with actress Dolores Del Rio and dancers Vera Zorina and Tilly Losch. Welles' and Nicolson's union resulted in one child, a daughter named Christopher.

The most famous and possibly most turbulent of all of Welles' romantic relationships was his marriage to actress Rita Hayworth. One of the most popular actresses of the 1940s, Hayworth was the epitome of Hollywood glamour and a seeming mismatch for the intellectual Welles. Hayworth and Welles married on Sept. 7, 1943, in a courthouse ceremony that came as a surprise to many of their peers. They had one child together — a daughter named Rebecca born in 1944. As documented in Orson Welles, A Biography, a combination of Welles' dalliances, including a passionate affair with Judy Garland, and Hayworth's alcoholism doomed the marriage, and the couple divorced in 1948.

In 1955, Welles married Italian actress Paola Mori. Welles met Mori in 1953, and they embarked on a passionate love affair while shooting the thriller, Mr. Arkadin. The union yielded one child — Welles' third daughter, Beatrice. Although Welles remained married to Mori until his death, the director kept a second home with his mistress, actress and filmmaker Oja Kodar.

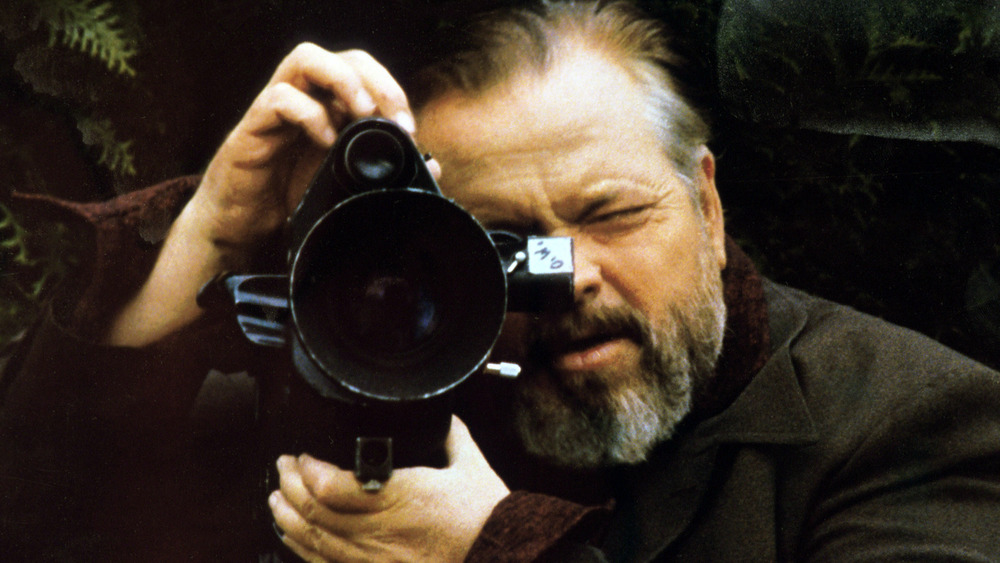

Orson Welles: rebel auteur

Although Orson Welles was recognized as a visionary director before the age of 30, he struggled to get his unique vision to the screen throughout his career. Even as critics, scholars, and film aficionados were hailing Citizen Kane cinema's greatest achievement, Welles found himself virtually unemployable in Hollywood and was forced to move abroad to seek funding for his movies (via Biography).

Welles learned his first hard lesson about the film industry with his second movie, 1942's The Magnificent Ambersons. Based on Booth Tarkington's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel about a wealthy family in decline at the turn of the century, Welles' film featured all the technical innovations that made Citizen Kane a spectacle couched in an equally grand but more intimate story. As detailed in a 2010 Vanity Fair retrospective, a disastrous test screening resulted in RKO re-cutting and reshooting portions of the film. Ultimately, The Magnificent Ambersons was cut from 132 to 88 minutes and dumped to a severely limited theatrical release.

According to Clinton Heylin, author of Despite the System: Orson Welles Versus the Hollywood Studios, Welles would spend the next 17 years of his career working within the studio system only to have his efforts blunted by the powers that be. Welles made six films in Hollywood, each of which would suffer from studio tampering. Three of Welles' studio films, The Stranger, The Lady From Shanghai, and Touch of Evil, were taken from Welles during editing and recut in an attempt to make them more commercially palatable.

The unfinished films of Orson Welles

While RKO was revising The Magnificent Ambersons, Orson Welles was on location in Latin America shooting It's All True. The film, intended as a blend of fiction and documentary, was to be Welles' third for RKO. As reported by the British Film Institute, support for Welles waned with a reshuffle of RKO's management. The studio recalled Welles before the film was completed and repurposed or destroyed much of the footage. It's All True contributed to giving Welles an unwarranted reputation for being unable to finish projects.

Following Touch of Evil, Welles left Hollywood to strike out on his own. His first project, an ambitious adaptation of Cervantes' Don Quixote, became one of the most notorious unfinished films of all time. Shot between 1957 and 1972, Don Quixote was largely improvised with Welles obsessively shooting and reshooting sequences. In the end it took the deaths of the film's lead actors to get the single-minded filmmaker to wrap the production.

In 2018, Welles' film, The Other Side of the Wind, starring the late filmmaker John Huston, was at last released after more than 40 years in development. Hampered by years of legal disputes and lack of funding, The Other Side of the Wind was originally conceived as a commercial comeback for Welles.

Other unrealized Welles films include a partially shot adaptation of the Charles Williams' novel Dead Calm, titled The Deep, and an experimental version of King Lear to be shot on video.

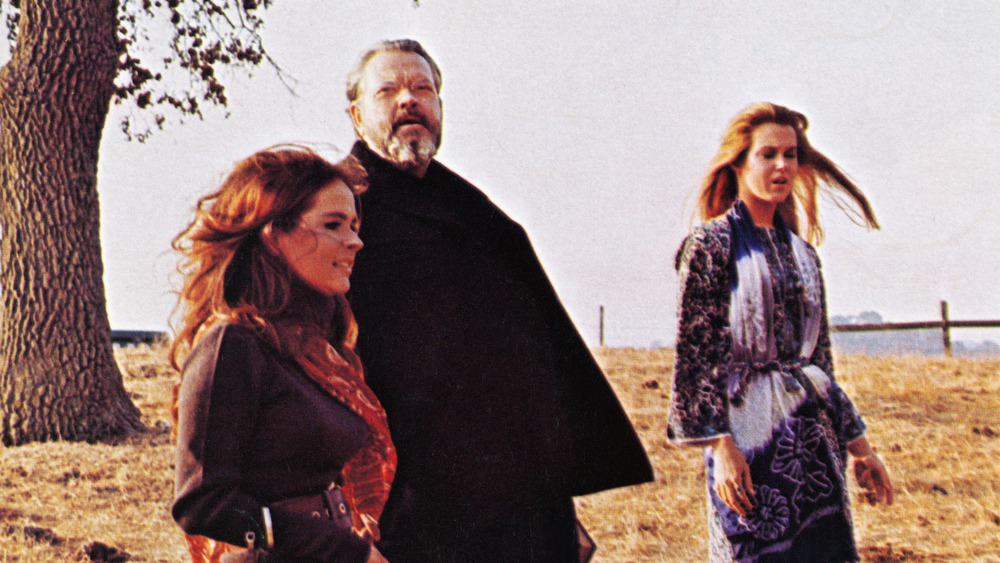

Orson Welles turned documentarian with F for Fake

Orson Welles' 1973 film, F for Fake, may not be as well known as such classics as Citizen Kane, The Stranger, or The Lady From Shanghai, but, in many ways, it encapsulates the filmmaker's obsessions better than any of his other works. Ostensibly a documentary, F for Fake combines elements of the film essay and the narrative motion picture to explore some of the 20th century's most celebrated hoaxes. Using the story of notorious art forger Elmyr de Hory as a launching point, Welles explores the nature of some of history's great frauds, hoaxes, and deceptions, including Clifford Irving's bogus "autobiography" of reclusive billionaire Howard Hughes, as well as his own famous 1938 broadcast of War of the Worlds.

As detailed by Jonathan Rosenbaum in an essay for The Criterion Collection, F for Fake is a supremely subversive film with a subtext that puts Welles' approach to his art in a surprising context.

Orson Welles grudgingly became a commercial spokesman

By the 1970s, Orson Welles was perhaps better known as a commercial spokesperson for everything from wine to frozen peas rather than a pioneering filmmaker. Although Welles felt the work was beneath him, it helped fund his later film projects, as well as keep him in a lifestyle that included maintaining households for his estranged wife Paola Mori and daughter Beatrice in Las Vegas and a Los Angeles home for his lover and creative partner, Oja Kodar.

As reported in a Newsweek feature focusing on Welles' so-called "late career slumming," Welles lamented his pitchman fate to author Gore Vidal. "I have an early call tomorrow," he told Vidal. "For a commercial. Dog food. . . No, I do not eat from the can on camera, but I celebrate the contents. Yes, I have fallen so low."

Despite his protestations, commercial work earned Welles close to a half a million dollars a year.

Orson Welles' final curtain

Despite his declining health, Orson Welles faced the 1980s with optimism and excitement. Although he continued to do what he described as "jobs of work," including his final role as the villain Unicron in Transformers: The Movie, released in 1986, Welles had a slate of projects in various stages of development and completion, including his long-simmering magnum opus Don Quixote, which he continued to tinker with until his death.

As reported by The New York Times, Welles died in his Los Angeles home of a heart attack on Oct. 10, 1985. He was 70 years old.

In an interview conducted by Entertainment Tonight just one week before he died, Welles summed up his feelings on his life and career. "I've had a wonderful, fascinating life. I can't complain," said Welles. "I'm the luckiest person I know, and I'd rather be remembered as a good guy than as a difficult genius."