Assassinations That Changed The Course Of History

The word "assassin" comes from a Persian order of soldiers called the Hashashun, who plotted the individual murders of political, military, and religious figures between around 1090 and 1277. Typically striking in public places, the rationale for targets was based both in their Shiite faith and in political grudges they amassed through their quest for power. Although the Hashashun were far fewer in territory and numbers than their enemies, they made themselves feared rivals with their precise attacks upon important figures. While the Hashashun were eventually defeated by the Mongols, says Britannica, the image of a figure lurking in the shadows waiting to strike has far outlasted them.

Unfortunately, the modern world is no stranger to such targeted killings. As people continue to disagree or wrong each other, and tensions reach their breaking point, prominent figures around the globe face violence. While it is difficult to truly measure the effect of a human life, here are 12 assassinations that changed the world forever.

Julius Caesar -- March 15, 44 B.C.E.

Julius Caesar's assassination is probably one of the most famous. Caesar was a Roman politician and general who was popular with the masses. After he was named dictator for life in 44 B.C.E., the Senate feared losing power and hatched a plan to end his life. According to the World History Encyclopedia, the group of conspirators included friends of Caesar and enemies alike.

As many as 60 senators were involved in the plot, though only a few are remembered today. Brutus is the main betrayer in William Shakespeare's version of events — which popularized the phrase "et tu, Brute?" — but in reality Decimus was the closest man to Caesar involved. For this reason he was chosen to convince Caesar to go to the meeting where his murder would take place, even though Caesar wanted to stay home.

On the Ides of March (the Roman name for the 15th of the month), Caesar was stabbed 23 times in an ambush on the Senate floor. The assailants fled to the Capitoline Hill, where they were met with a mix of support and disgust. While the conspirators had hoped to restore the status quo and regain power lost under Caesar, the ultimate effect of his killing was the rise of Octavian, also known as Augustus, who consolidated power and became the first emperor of Rome. In essence, the opposite happened, and power shifted hands as the Republic turned to an Empire.

200 Aztec nobles -- 1520

In the 16th century, the Spanish crown tasked Hernán Cortés with establishing colonies near the West Indies. He set his sights on conquering the great Aztec civilization. Cortés mounted a plan to take the capital of Tenochtitlan from the inside, using chief Monteczuma as a puppet to control the population. But after devising his plan, Cortés received word of a Spanish crew out to arrest him for refusing to return from his conquest. He fled Tenochtitlan, leaving his carefully laid plan in the hands of his right hand man, Pedro de Alvarado.

While Cortés was gone, Alvarado and his men observed a religious festival, Toxcatl, attended by many important members of Aztec society. Seeing all these powerful people in one room made Alvarado fear a plot, and based on this suspicion, he called upon his forces to stop the uprising before it could start. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, they executed 200 of the most important people in Tenochtitlan.

The incident caused a massive uprising where the Aztecs drove the Spanish from the city. However, the Aztecs' social structure had been decapitated, and much of their armed forces along with it. The Spanish soon returned to launch a siege that ended in the fall of Tenochtitlan. The battle represented the end of the Aztec empire and the completion of the first stage of Spanish colonization. All of Mesoamerica would soon be brought under harsh Spanish rule, forever changing the continent.

Oda Nobunaga -- June 21, 1582

Oda Nobunaga was a warrior and politician in 16th century Japan. He is known as the first great uniter of Japan, as his military conquest united over half of Japanese provinces under his singular rule and helped end the Sengoku (Warring States) period. The Sengoku period was famous for its samurai, trained fighters who operated on behalf of feudal lords, or, in Nobunaga's case, their own political gain (via World History Encyclopedia).

Nobunaga's great success caused the envy of many men, including one of his closest vassals, who betrayed him. He directed thousands of soldiers to ambush Nobunaga and his party in the Honno-ji temple in what is now known as the Honno-ji Incident. Nobunaga knew he was outnumbered and thus instructed his crew to hold them off while he committed Japanese ritual suicide.

Although his reign was accompanied by much violence, it paved the way for a more peaceful era after the country was unified into a singular entity. Thanks to Nobunaga and the other two great uniters, Japan saw nearly 200 years of peace after the Sengoku period. The years following the Sengoku period are known as the Edo period, a time of great cultural and economic development. The art of the Edo period, such as Hokusai's The Great Wave off Kanagawa, remains of great cultural importance across the globe today.

Abraham Lincoln -- April 15, 1865

By 1865, John Wilkes Booth had enough of Abraham Lincoln. Booth, an actor and vocal proponent of slavery, became a part of several plots to kidnap the president and end the war. When the plots failed and the war ended, an enraged Booth hatched a plan, says Britannica, to assassinate the president, vice president, and secretary of state at the same time. Booth was to go for the president, sneaking into his box at Ford's theater.

When the time came, he snuck into the box and shot Lincoln through the back of the head. He proceeded to jump onto the stage and yell something — either the state motto of Virginia or "the South is avenged," according to conflicting reports — before fleeing the theater on horseback. Lincoln was taken into care but died early the next morning.

Lincoln was replaced by Vice President Andrew Johnson, a former senator who remained loyal to the Union despite his Southern heritage. However, Johnson's leniency towards the South in the Reconstruction era resulted in near universal amnesty for Confederates, meaning that state leadership did not change much following the war. Recycled Southern state governments sought to maintain the status quo as much as possible, writing strict "black codes” that essentially put Black southerners in the same position as before the war (via History).

Franz Ferdinand -- June 28, 1914

After Austria-Hungary annexed Bosnia-Herzegovina, Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand journeyed to his new territorial acquisition to view symbolic military exercises. The annexation was quite controversial as Serbian and Bosnian nationalist sects had been growing since Austria first colonized Bosnia in 1878, and the exercises would be a show of power meant to dissuade any revolutionaries.

Because of these tensions, Ferdinand's visit turned out to be a markedly bad idea — he was almost assassinated multiple times by the revolutionary group Young Bosnians. After smuggling bombs, guns, and even cyanide capsules across the Serbian border and into Bosnia (with History reporting that it has yet to be determined whether the Serbian government was involved or not), the Young Bosnians began to strike. They threw a bomb at the archduke's car, which missed but injured bystanders, and were in close enough range to shoot but chickened out.

Despite these near-death experiences, the archduke and his wife decided to remain in-country for their final scheduled event. As they were leaving, driving quickly to avoid more bombs, they accidentally turned down a side street where one of the disgruntled Young Bosnians happened to be — and no, he was not eating a sandwich. Gavrilo Princip saw his moment and shot, striking both Ferdinand and his wife. The two died at the scene, and Princip was taken into custody. The violent event led to World War I, with Austria-Hungary essentially blaming Serbia for the blood of its son, and different European powers taking sides.

A variety of important Guatemalan figures -- 1954

Guatemala was the first nation to fall victim to a CIA-backed coup in the Cold War era. These coups rocked Latin America and are one of the reasons behind continued destabilization in the continent in the modern day. They typically consisted of the United States backing a cooperative, right-winged candidate and rigging elections in their favor, then violently disposing of the (democratically elected but bad for business) opposition in a series of planned attacks.

Guatemala was no different. Democratically elected President Jacobo Arbenz was hated by American officials, who called his policies "intensely nationalistic" and based in an "anti-foreign inferiority complex," (via the NSA Archive). In retaliation, the U.S. worked with Nicaraguan dictator Anastacio Somoza to overthrow Arbenz. Arbenz eventually resigned, and under pressure from the CIA-backed opposition movement, he fled the country. But the CIA still had an "A list," 58 Guatemalans that had to go. They, along with hundreds of other Guatemalans involved in the pre-coup government, were systematically targeted and killed. Documents by the CIA in 1997 revealed 1,400 of an estimated 10,000 pages on the plan to destabilize Guatemala, including and entire assassination instructional guide.

Although the case of Guatemala is not unique, the CIA's success in controlling the Banana Republic set them on a collision course with the rest of the continent. From Brazil and the Dominican Republic in the 1960s to Honduras and Venezuela in the 2000s, such interventions have caused decades of destabilization and violence.

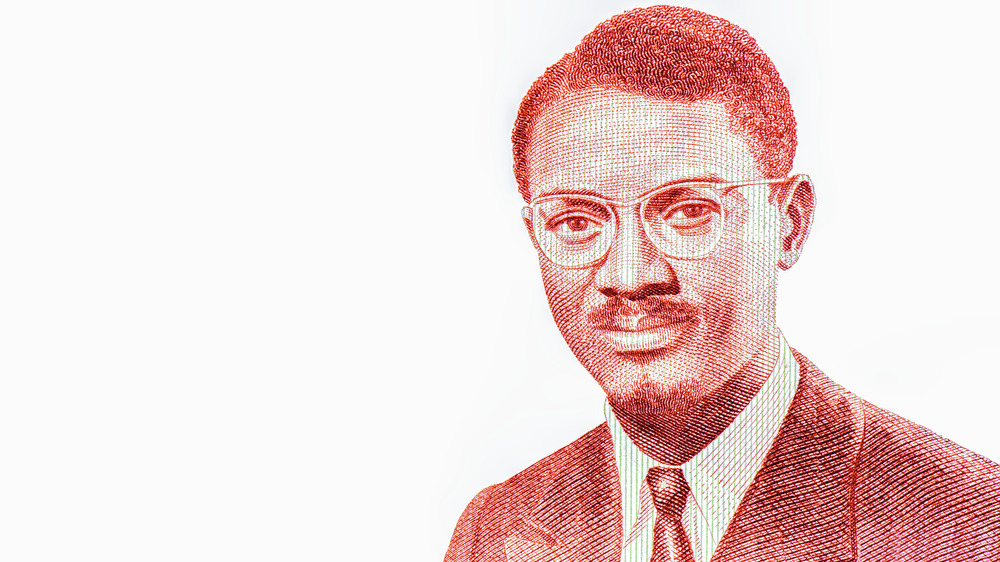

Patrice Lumumba -- January 17, 1961

Patrice Lumumba was a renowned anti-colonial, Pan-Africanist thinker and political leader in the Democratic Republic of the Congo's (DRC) fight for independence from Belgium. Belgium accidentally got Lumumba elected as the DRC's first prime minister when they held democratic elections in an attempt to install a puppet regime. Despite several attempts to deny him, Lumumba took power and instituted a number of progressive policies.

But Belgium wasn't giving up their mineral-rich colony without a fight. Lumumba called on the Soviets for help defending against the colonial oppressors, says Britannica, a move which angered the Western world due to Cold War tensions (it is worth mentioning he had called upon the U.N. for help first, and they refused). Chaos ensued, and multiple Western powers targeted Lumumba's life. Multiple plans were launched to incapacitate him, including hiring assassins and abductors. According to The New York Times, the CIA even flew in a rare poison to lace his toothpaste with. After a series of mishaps and failed attempts, Lumumba was kidnapped, tortured, and shot to death by a firing squad, reports The Brussels Times.

Lumumba's death, though brutal, was not unique. His was one of six such murders that decade, where African leaders' deaths were plotted by Western powers. The deaths of Lumumba and his peers had a lasting effect on Western-African relations and has set the continent back majorly in terms of progressive policies. Tensions remain high even today, prompting Belgium to formally apologize in 2018 for their role in the murder.

Hendrik Verwoerd -- September 6, 1966

Sometimes referred to as the "architect of apartheid," (via Smithsonian Magazine) Hendrik Verwoerd was the prime minister of South Africa from 1958 until his death in 1966. According to History professor Christopher Marx, Verwoerd's series of degrees in psychology and sociology made him a fundamental player in creating institutions of racial oppression across South Africa.

It perhaps comes as no surprise that the man who came to epitomize racial animosity in South Africa faced not one but two assassination attempts. In the first attempt, carried out by businessman David Pratt, Verwoerd sustained two shots to the face but survived. Six years later, parliamentary page Dimitri Tsafendas stabbed Verwoerd to death after ambushing him on the Senate floor. Both Pratt and Tsafendas were tried under the pretense of lunacy.

The categorization of these individuals as insane was meant to deflect negativity from the apartheid regime, and yet, even though the system has fallen, the story of Tsafendas and Pratt remain the same in popular consciousness. The enduring label of insanity placed upon those intent to destroy apartheid shows that great care must be taken when nations seek to reckon with their violent pasts. Propaganda can have a powerful hold on a society, even after the systems it meant to protect have been dismantled.

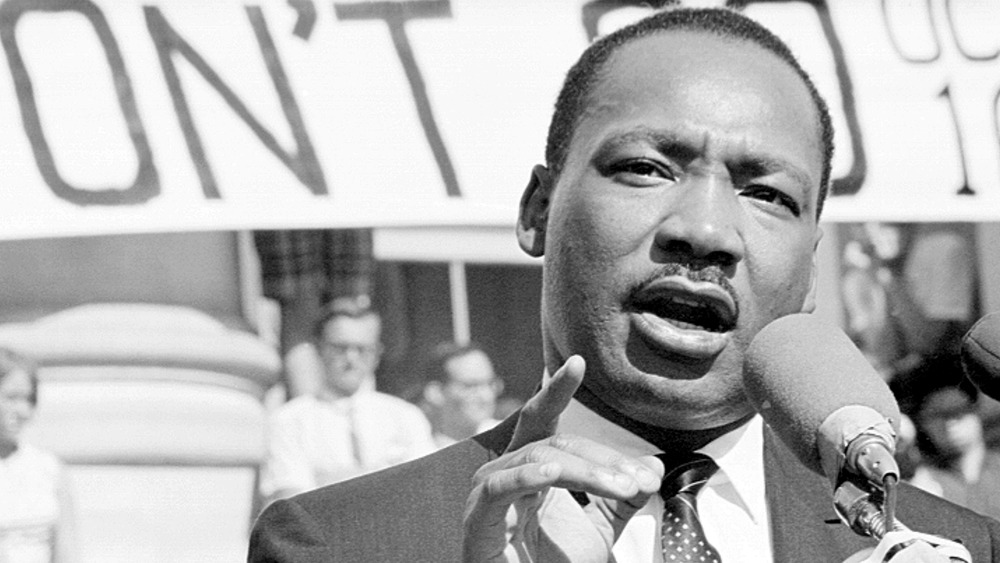

Martin Luther King Jr. -- April 4, 1968

Martin Luther King Jr. was standing on the balcony of a Memphis motel when he was murdered, reports History. The manhunt that followed led to the arrest of James Earl Ray, an escaped convict, who was apprehended in London's Heathrow airport. He confessed nearly a year later and was charged with a 99-year sentence for the murder of the civil rights leader.

Since the trial, King's family has repeatedly asserted their belief in Ray's innocence. Their skepticism lies in the FBI's repeated torture of King — the bureau once sent a tape to his house that sounded like him having an affair and threatened to publish it unless he killed himself — the convenient bag of evidence left at the scene, and Ray's post-trial insistence that he was set up by a man named Raoul. Though the government has supposedly debunked the Raoul story, a man came forward in 1993 with conflicting evidence. He owned the diner under the hotel room Ray supposedly operated out of and confessed in civil court to being part of a government-led plan to assassinate King for which Ray was the scapegoat. Based on this evidence, jurors at the trial found the government guilty of conspiring to assassinate the civil rights leader.

MLK's death led to the expedited passing of the Fair Housing Act (1968), which King had been campaigning for leading up to his death. According to History, the assassination also heightened tensions between Black and white Americans.

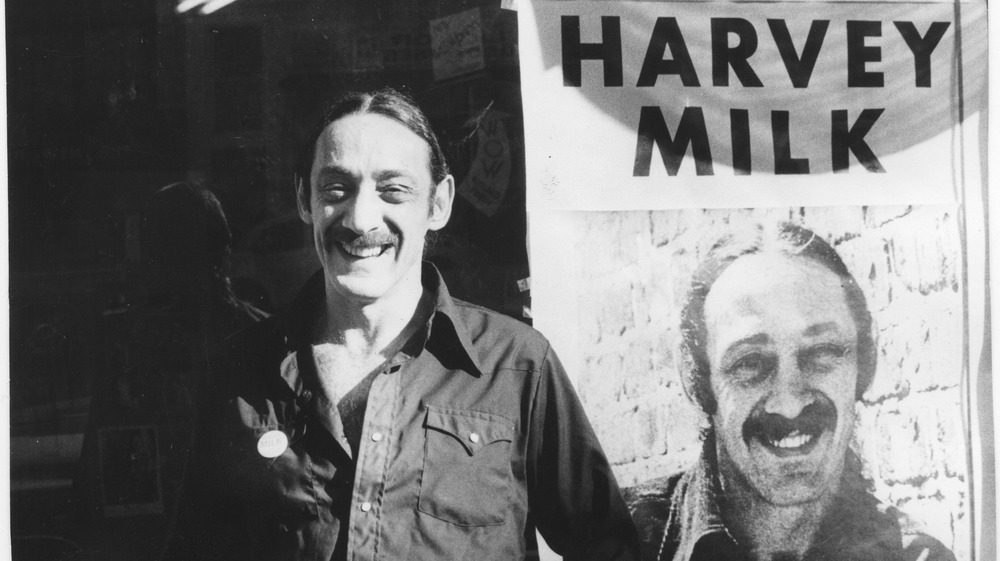

Harvey Milk -- November 27, 1978

Harvey Milk was the first openly gay man to sit on the San Francisco board of supervisors, and only the fifth openly gay person in the country to take public office. After his 1977 election, Milk dedicated himself to issues like fair housing and ending workplace discrimination and even made friends with political peers who thought differently from himself. One such frenemy was Dan White, a pro-police Catholic, who thought so highly of Milk he invited him to his son's baptism.

Yet nearly a year later, White shot both Milk and then mayor George Moscone in their respective city hall offices. Those close to White, according to San Francisco Weekly, claim his main motive for the murders was feeling politically betrayed, not zealous homophobia. White had quit his position during a breakdown, and when he begged the mayor for his job back, Milk lobbied against him. No matter his intent, White killed one of America's few openly gay politicians at the time.

After White received a lenient sentence, protests broke out across the city. What resulted were the White Night riots, a series of clashes between gay people and the police (who had fundraised for White's defense team) after peaceful protests were met with confrontation. The events brought gay issues to greater prominence across the U.S., and Milk's legacy carved the way for a series of LGBTQ+ candidates to take office.

Yitzhak Rabin -- November 4, 1995

Yitzhak Rabin dedicated his term in office to peace. Before his untimely death, he had committed to Palestinian self-rule and ended a war with Jordan that spanned nearly half a century. Rabin, a former soldier, had spent 30 years fighting against the accords he now forged, making him a symbol of the peace that could be achieved in the region.

Not everyone wanted peace. The Zionists, a group of Israeli nationalists who opposed the recognition of Palestine as a separate and legitimate state, did not agree with Rabin's tactics. Multiple extremist rabbis even issued statements saying it would be acceptable to murder Rabin, reports The New Yorker.

It was for this reason that, when attending a peace rally, Rabin's cohort had urged him to wear a bulletproof vest. But Rabin loved the people of Israel so deeply he refused to believe someone in his nation would want to hurt him. This belief proved to be fatal, as Rabin was shot twice in the back by devout Zionist Yigal Amir.

Multiple news outlets called the assassination one of the most successful in political history. Amir got exactly what he wanted, as the peace between Israel and Palestine that had come so close under Rabin quickly crumbled under his successors. Conflict in the region continues to be a hot-button issue today, and with increasing violence — according to human rights watch group B'tselem, Israel killed an estimated 133 Palestinians in 2020 in Palestine occupied territory.

Benazir Bhutto -- December 27, 2007

Benazir Bhutto was the first female leader to be democratically elected to a majority Muslim nation, becoming prime minister of Pakistan in 1988. Despite her milestone achievement, Bhutto was somewhat of a controversial figure. After being convicted of corruption during her two terms in office (which also involved the assassination of her brother and a failed coup d'etat), the politician returned from self-exile after eight years to run for a third term.

Bhutto's prospects for winning a third term looked bright. But it would be dangerous, warned her competitor and current head of state Pervez Musharraf. Despite his warning, Musharraf denied her foreign protection, instead offering her bodyguards from the Pakistani police force, writes author Heraldo Muñoz. And the protection proved necessary — after one unsuccessful attempt in October of 2007, Bhutto was killed the following December.

Though the Pakistani taliban initially claimed her death, the Pakistani government's handling of the situation led to much suspicion. The official narrative was that Bhutto had died when shrapnel from a suicide bomber's vest cracked her skull, but doctors performing her autopsy asserted they were told to keep quiet about the gunshot wounds they found. Sources close to Bhutto also claim she received a threatening phone call from Musharraf just months before the election. Though Bhutto's time in office was far from perfect, the rift between a political and military elite that became apparent during her two terms were only widened by her violent death.