The Truth About The Deadliest Day Of The Civil War

September 17, 1862. Sharpsburg, Maryland. The American Civil War had been raging for over a year, and the end still wouldn't be in sight for at least a few more. But history was about to be made, and not in a good way.

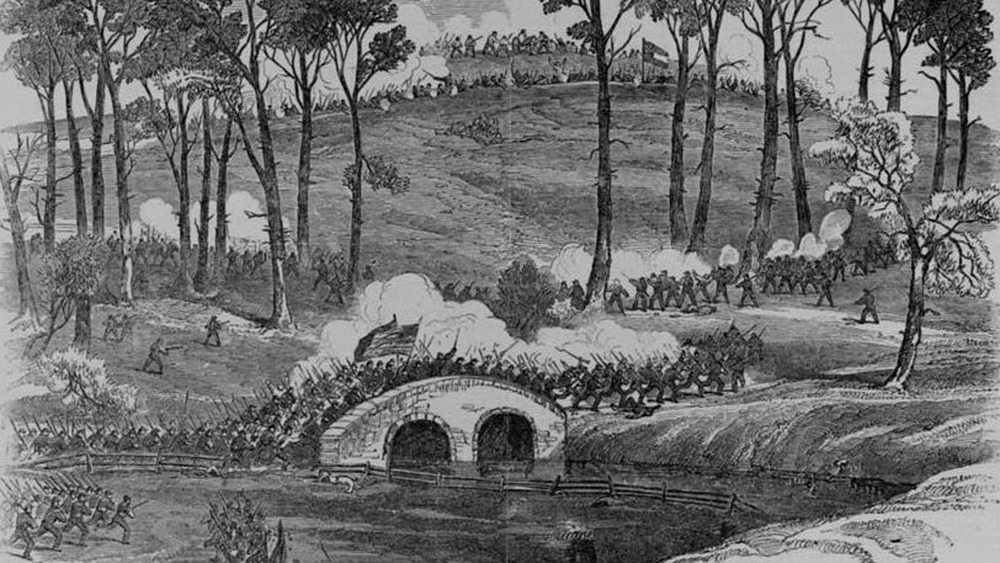

Union and Confederate troops clashed at the Cornfield and Bloody Lane for hours, gunfire ringing in their ears and the bodies piling up by the thousands. The men were scared, and the commanders feared for the troops under their control, and eventually, the Confederate Army was pushed back to a bridge over Antietam Creek, holding a bluff that gave them the literal high ground. But the Union eventually allowed the Confederate Army to retreat back to Virginia and declared the battle a victory.

And it was, in some ways and in the long-term, but at the same time, it was sort of a hollow one. The Battle of Antietam, as the fight is now called, had a profound impact on the rest of the war, but it's more well known for its other title: the deadliest day of the Civil War. There's a lot to unpack here, including some really unfortunate (and sadly unsurprising) truths about the battle.

A high casualty count

All wars are remembered for being violent and for being bloody, and for all the death and destruction that they leave in their wake, but just looking at the numbers, nothing in American history compares to the Civil War. And this isn't to diminish any other war; the statistics just speak for themselves.

According to American Battlefield Trust, Civil War casualties numbered somewhere around 620,000 (about 2 percent of the American population at the time); that's more than American casualties in both World Wars combined, and more than every other war combined until Vietnam. And that's not counting the missing, captured, or wounded; taken all together, the casualty number is closer to 1.5 million. (Not to mention that other sources believe the death toll to be closer to 850,000, in which case, no other war or combined count is even close).

And battles like Antietam are a big part of why the count is so high — Constituting America reports over 12,000 dead, wounded, or missing on the Union side and over 10,000 for the Confederacy. But even with 23,000 casualties, it's still pretty far from the bloodiest battle of the whole war. A handful are within 10,000 casualties more, while Gettysburg has over double the casualties at 51,000. But Antietam has its own terrible title as the most deadly single-day battle (via History). 23,000 people dead or wounded in under 24 hours — it's truly horrific.

The Battle of Antietam wasn't meant to be important

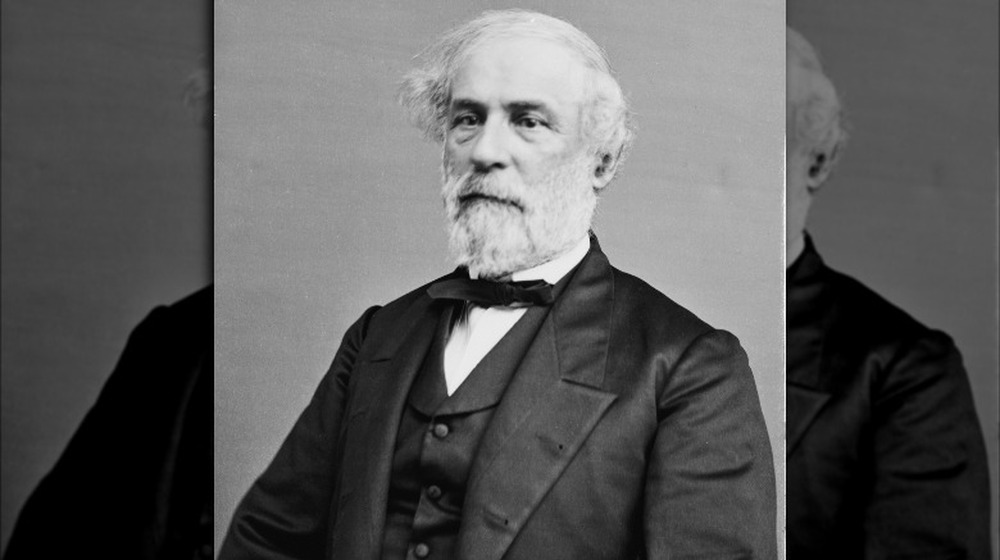

It was 1862, and things weren't going well for the Union. There were a number of reasons why, according to American Battlefield Trust, but it mostly comes down to demoralization and a few less-than-flattering military losses. That gave the Confederates an opportunity, and one that General Robert E. Lee (pictured) was going to capitalize on. He knew that invading Maryland would end up being a real blow to the Union as a whole; the Confederacy could really go on the offensive and start encroaching on Union lands. That spawned the Maryland Campaign, Lee's ambitious plan to pretty much sweep through the state and capture Union-controlled areas.

Here's the thing, though: Antietam wasn't exactly part of those plans. As NPR says, Antietam wasn't a strategic position; it's just where the Confederate army fell back to when things went awry. At best, it would just be a place where they could launch a larger campaign further north. A Confederate victory up north could have meant something. Antietam itself didn't really mean much — the actual lines only shifted about a hundred yards total.

That said, it could've been insanely important. McClellan allowed Lee to retreat (and regroup), and refused to pursue him, feeling he'd done his job. But, as History says — and as Lincoln pointed out to him — McClellan could've decimated the Confederate Army right then and there. The war might've been won that day, but the chance slipped away.

The Battle of Antietam involved close-range fighting

The fighting that took place at Antietam was absolutely terrifying. And it's for more than just the fact it's a battle and a lot of people died. That's true in just about any case, but the fighting at Antietam was up-close and personal.

So, part of the Battle of Antietam took place at the Cornfield — a literal cornfield — and that part of the battle went on for a full eight hours (via History). But the thing about this is the fact that it was a relatively small space. As NPR says, from the start, the gunfire was really concentrated, opening with just 200 yards of distance between the two armies. Then from there, things just got even closer, even down to a 100 yards or less.

Basically, at certain points, a soldier could just pop up and immediately see the enemy, so in the case of the Confederates at Sunken Road (better known as "Bloody Lane"), they were caught in a death trap, Union soldiers descending almost directly on top of them. Death was quite literally upon them.

A hailstorm of bullets

The soldiers at Antietam had some really vivid memories of the battle, hours on end during which they were surrounded by death. And that was true, no matter the side.

Sebastian Duncan recalled the fear at hearing shots whizz over their heads, the shells bursting into splinters above them, all the men ducking on instinct, even if the shots were passing more than a hundred feet over them (via HistoryNet). Eventually, they realized the distance, but that didn't make anyone brave enough to try and poke their heads up for a better view. And with muskets rattling in the distance, the waves of gunshots ringing like explosions through the air, who could blame them?

But for others, the bullets truly did rain down on them: Thomas Evans wrote how, sometimes, the shells were exploding just over their heads, showering them in shattered bits of metal (via National Park Service). Another soldier, Robert Kellogg, had a shell burst so close to him that it blew dirt right into his face. With bullets flying through the air, knowing they were hitting so close, the instinct was just to hope for a little luck and stay out of the way.

The Confederate soldiers in particular had their share of it at Sunken Road. Taking cover in a ditch in the road, their position soon became a death trap where shots rained down on them from every direction, and their only salvation was escape through the rear (via NPR).

The scene at the hospitals

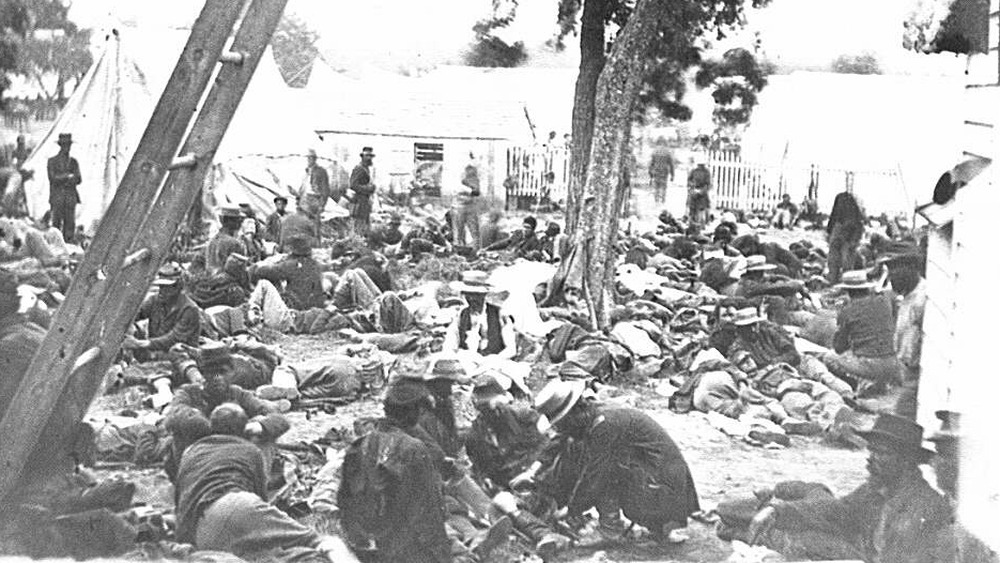

It's no far stretch to call Antietam the bloodiest day in all of American military history, and the devastation on the battlefield itself — in the midst of all the fighting — is one of the places that anyone could've seen that. But William Child, a surgeon writing from a battlefield hospital near Sharpsburg believed that, maybe, it was the days after the battle which might be even worse (via National Park Service).

In the aftermath of the battle, his work was never-ending, dressing wounds quite literally from dawn 'til dusk for multiple days on end. George Allen added that, in most cases, the wounded were basically piled into the hospitals, tightly packed together, where they awaited treatment (which was, more than likely, going to be amputation). But the part that was really bad wasn't necessarily the exhaustion and workload, or even the nature of the work; it was the difference between the dead and the wounded.

A bunch of soldiers described the carnage on the battlefield, painting horrifically vivid images of their fallen comrades, but at least the dead were just gone. The wounded had to suffer through intense and burning pain, the kind that's too hard to think through (via HistoryNet), and it wasn't easy for them or the doctors who treated them. It was all so bad, Child believed it was an act of God, punishment for a great sin, and the kind that he just hoped would end soon.

Bodies falling on the battlefield

It's really, really easy to find accounts of this battle which are just filled with gruesome and horrifying imagery, the things that the soldiers saw as people fell left and right.

Soldiers struck by a bullet would be sent sprawling backwards, and any of them not immediately killed from a shot to the head or heart would be left to writhe in pain (via National Park Service). Christoph Niederer had an even more disturbing story; he felt a blow to his shoulder, but also something wet splatter on his face. Looking over, he saw a fellow soldier "lacked the upper part of his head, and almost all his brains had gone into the face of the man next to him" (via HistoryNet). There really isn't much more that needs to be said; it's just a terrifying image.

But aside from the blood and gore, there are other stories that are just sad. One soldier staggered in the midst of battle, not from a wound, but from finding his father lying dead on the ground. R.R. Dawes wrote about his captain owning a dog which was loyal all the way until the end, by his side as he fell. J.D. Hicks found the body of a teenaged drummer boy — not even a soldier — pale and lifeless with a bullet in his forehead, but a smile still on his face and his drum lying next to him, "never to be tapped again."

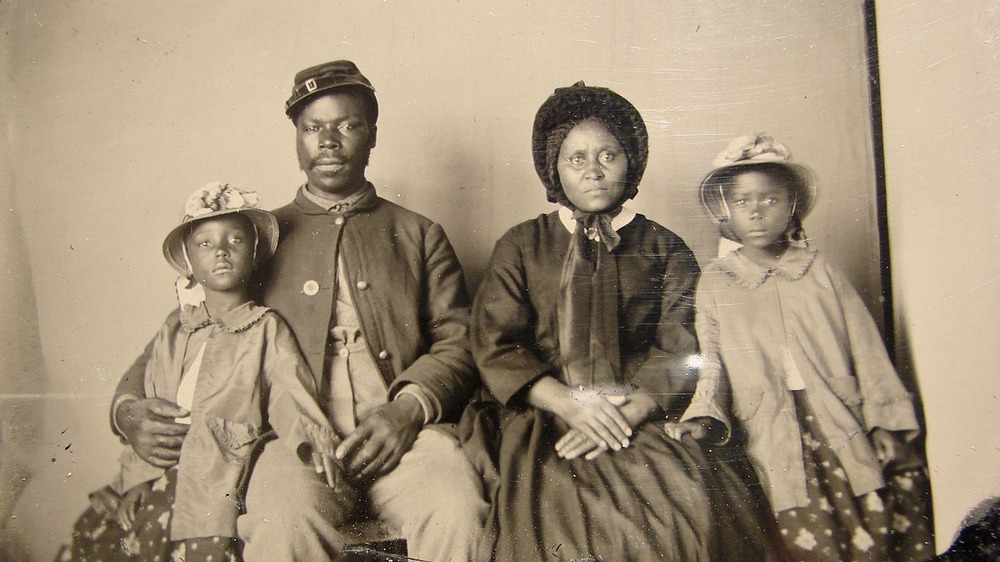

The soldiers all had families

This is one of those things that everyone does know, but sort of just deserves to be said. All of the soldiers in this battle were people, not just numbers on a casualty list. All of them had families, and no small number of the accounts of the battle come from letters. A lot of them just missed everyone back home, wanting little more than to see them again, hoping for letters and the happiness they got from being able to hear from them, at the very least (via National Park Service). Many times, those letters would also include individual things to tell different people back home — personal and more intimate responses.

And there are stories filled with a lot of longing. William Child wrote to his wife about a dream he had, where he was back home, back in his normal life, feeling like the dream was real. It reads kind of like a scene in a movie, lingering a bit on the moment when he got to be with his wife — when she kissed him and told him that she loved him. It's intimate and bittersweet, a dream in the middle of him tending to so many wounded.

Another soldier also wrote home, not sad or despairing over his wounds, but from the fact that someone had stolen something priceless from him: a book containing a lock of his wife's hair.

The Battle of Antietam didn't have to happen

As History tells it, on September 13, the Union army under General George McClellan (pictured) was stationed just outside Frederick, Maryland. Sergeant John Closs and Corporal Barton Mitchell happened upon a lucky find: three cigars discarded on the ground. But it was more than that. A paper was wrapped around them, addressed to Confederate General D.H. Hill and titled Special Order No. 191.

This was a major find. McClellan and the Union had been completely confounded by Lee's strategies, but suddenly, they had their hands on the Confederate army's exact plans, coming directly from Lee's adjutant general. Suddenly, they knew that Lee's army was spread thin, separated into five parts over 30 miles, and not even that far away. It was a massive tactical advantage.

Except, McClellan did nothing about it.

History Daily explains that it would've been so easy for the Union to completely decimate the Confederate army in one fell swoop. They could've taken them out piece by piece — a bunch of small battles between a tiny army and a much larger one. It would've been the easiest Union victory, and one with a relatively small casualty count. But McClellan completely squandered the opportunity. He took a full 18 hours to mobilize his troops, at which point Lee already guessed the Union knew about his plans and had regrouped his forces, and then the bloodshed of Antietam wasn't far behind.

Photographs of Antietam brought the battlefield home

The Civil War saw a pretty important first in history: Antietam was one of the first battles to ever be photographed showing the tragic, harsh realities of war, according to the National Park Service. See, photography had just become a thing earlier in the century, the first photographic images getting produced in the late 1830s. But the entire process of producing photographs was...complicated. It's the entire tedious process with darkrooms, but with some added layers of complexity that comes from necessary chemicals that had to be handled with a lot of care.

So battlefields were generally too chaotic for photography, as The Met puts it. Photographers definitely couldn't get any footage of the battle itself, but they could document the preparation and the aftermath. And that's the big part: the aftermath. Antietam was the first battlefield photographed before the dead were buried. The first battlefield that anyone could see, littered with the bodies and the dead and all.

Those photographs went up into galleries, and for the first time, people at home could see just how terrible battle was. They could see how bloody and grim it was without ever being there themselves; all of a sudden, the war was brought right to their doorstep, and they could just about see it all firsthand.

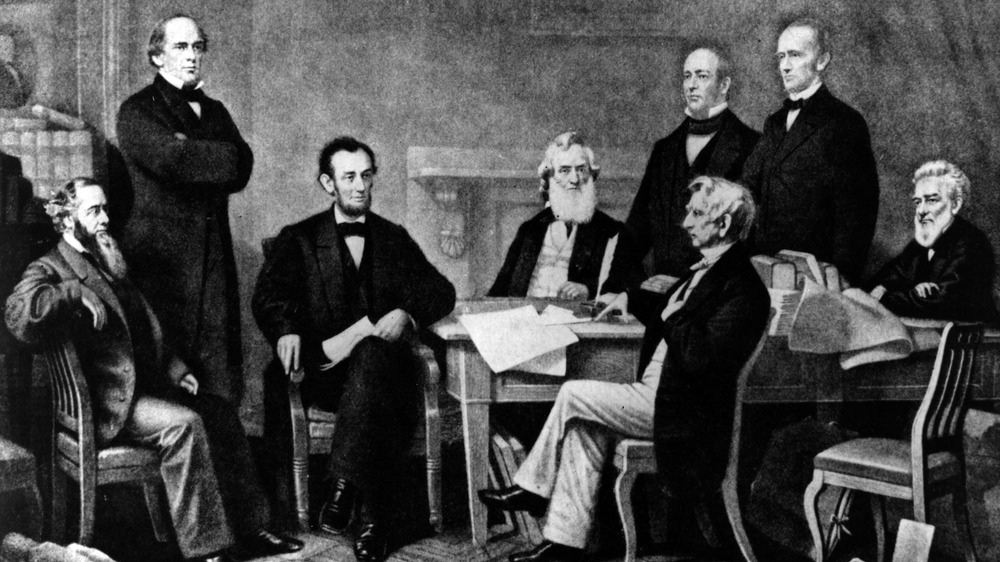

The Battle of Antietam led to the Emancipation Proclamation

The Battle of Antietam has become infamous for the amount of blood shed in such a small amount of time, but it's also become famous for other reasons, like inadvertently changing the tide of the Civil War. According to Constituting America, Abraham Lincoln had been intending to find a way to end slavery. His solution to that problem was the Emancipation Proclamation — a document which would free slaves in the South as a part of Lincoln's wartime powers (while exempting slaves in the Border States, in order to keep those states from running into the arms of the Confederacy).

But the Union wasn't in a great place at the time when Lincoln first penned it. As History says, Union morale was already low, the military despairing because of lost battles, and the public at large frustrated with how long the war was taking. So Lincoln's cabinet were worried about him delivering such a speech; there were too many things unsure, and they counselled him to wait for a military victory. It would be best to deliver the Emancipation Proclamation from a place of strength.

Antietam was exactly that. Casualties were high (to the point that many historians would actually call the battle a stalemate), but the Union claimed it as a victory regardless. It was the best chance the Union was going to get, and so Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing the slaves as of the start of 1863.

Europe stayed out of the Civil War because of Antietam

The Union had a lot to deal with in 1862: a demoralized army, disappointing military defeats, unpopular legislation, and the like (via History). But there was another looming problem: Europe. Europe imported Southern cotton, and they might end up recognizing the Confederacy. Backing by a major European power could really change things.

And that was a really legitimate concern. Europe was definitely watching from the sidelines. England and France had initially stated their neutrality, their respective governments not willing to support rebels who believed in slavery (both countries had already abolished the practice), and expecting a quick Union victory (via Encyclopedia.com). But that quick victory didn't happen, and the two European powers started to reconsider. European nobility identified with Southern gentility, and the governments thought that the US was becoming too powerful in world affairs; the nation splitting would reset the balance of power. Plus, the Confederacy proved their military capability, and an international incident painted the Union badly. And this war wasn't — officially, at least — just about slavery; supporting the Confederacy didn't necessarily have to equate to supporting slavery, so maybe it wouldn't be the worst idea.

Antietam flipped that around, though. It gave the Union a victory, and then it led directly to the Emancipation Proclamation. Suddenly, the war was about slavery, and the Confederacy was the villain for supporting it. At that point, European powers pulled out entirely; they couldn't support the Confederacy without their people hating them.