The True Story Of American Medical Student Grave Robbers

Grave robbing has been a thing for as long as humans have been burying their dead beneath the ground. Enterprising thieves, knowing that the dead were sometimes buried with jewelry or other keepsakes that could be sold for profit, knew that surreptitiously digging up the deceased was a quick and easy way to make some cash.

However, for a time in U.S. and British history, grave robbing was less of a haphazard crime of opportunity and more of a full-fledged industry, not unlike the illegal drug trade today. Changing times provided grave robbers with a desperate market for "product" (which is to say, fresh corpses). To meet the demand, illicit transportation and distribution channels were set up. What's more, there was a constant supply of fresh corpses, the bodies of people about whom few, if any, cared what happened to them.

The reason for the new demand for fresh corpses? The emerging science of medicine. For centuries, medicine had been a slapdash industry that relied as much on folklore and superstition as it did actual science. However, as scientific knowledge advanced, medical schools relied on dissecting cadavers to advance their knowledge, according to JSTOR.

Initially, governments would provide the bodies of criminals to be dissected. However, at the time the concept of donating your body to science didn't exist; since the bodies of criminals were almost uniformly the ones dissected, no respectable person would permit their body to be dissected after death due to the practice's association with criminality.

Unfortunately, in the U.S. and the U.K. at least, the demand for corpses to study far outpaced the supply, leading to a booming grave-robbing trade that flourished in both countries for a period of time in the 19th century.

Baltimore was ground zero for the grave-robbing trade in the US

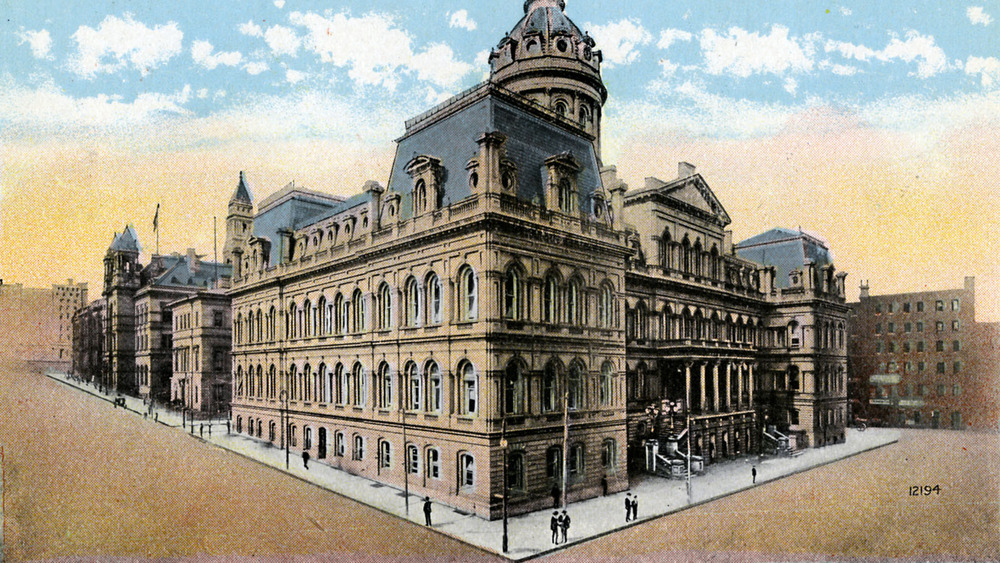

The city known at the time as the "Monumental City," according to Smithsonian, was, for seven decades, at the center of a perfect storm of sorts when it came to the illicit cadaver trade.

There were multiple reasons for this, not the least of which is the fact that the city was home to six medical schools, all of which needed fresh cadavers for their students to study. Further, the city's climate was more agreeable to grave robbing than other major East Coast cities, due to the fact that the ground infrequently froze solid and, thus, was easier to dig up; one famed grave robber bragged that every winter he would take orders from medical schools with less agreeable climates, in much the same way that a distributor of meat might take orders for beef or pork. What's more, the city's famed Baltimore & Ohio Railroad provided a means of shipping freshly-dug corpses across the country.

There was a racial component to the practice as well. Due to the city's location on the border between the free North and the slave South, enterprising grave robbers were never far from a fresh supply of bodies of deceased slaves or free Blacks.

It was almost comically easy to get away with grave robbing

For Baltimore's body snatchers, relieving a grave of the corpse it held had been refined down to a science. The thieves would dig a hole at the head of the fresh grave, break the opening of the coffin, use a hook to gain a hold on the body's neck or armpit, pull it out, and hurry it away in a flash, according to Smithsonian.

The bandits even had a pet name for their group, calling themselves "resurrectionists."

Oftentimes, the dirty work of actually digging up and removing the body would be farmed out to criminals, vagrants, or to anyone desperate enough for some money. Just as often, doctors themselves would participate in the practice.

Politicians were loath to do much about it, police looked the other way even though the practice was technically illegal, cemeteries rarely took action (because they were often in cahoots with the grave robbers), and doctors and medical school officials wrote the practice off as a necessary evil, according to PBS.

In one illustrative case out of Baltimore, several people affiliated with a medical school were brought into court to answer for a grave robbery after the thieves made the mistake of breaking into the grave of a "handsomely attired lady" from a "wealthy and respectable family," rather than that of a gutter rat or criminal, and her family complained.

None other than Dr. L. McLane Tiffany, the dean of the medical school, bailed out the thieves and hired a staunchly segregationist lawyer to defend them — shocking at the time, considering that two of the accused were Black. All four were acquitted.

The practice ended not with a bang, but with a whimper

The practice of robbing graves and supplying the corpses to medical schools had largely come to an end by the turn of the 20th century, according to PBS. But it wasn't any one thing that put an end to the practice, but rather a culmination of several trends.

By the mid-1800s, according to the book A Traffic of Dead Bodies: Anatomy and Embodied Social Identity in Nineteenth-century America, several states passed so-called "Anatomy Acts," which allowed medical schools to use unclaimed bodies — largely those of the poor, who died in hospitals, workhouses, or other institutions and who didn't have the money for a proper burial, rather than just condemned criminals.

Further, as the Journal of the American Medical Association notes, by 1900 a shift had taken place in the way future physicians were instructed. Medical schools expected their students to be familiar with the scientific method before they even applied, and the study of gross anatomy became less important in a doctor's education, lessening the demand for fresh corpses to dissect.

It wasn't until 1968 and the passage of the Uniform Anatomy Gift Act allowed residents of all 50 states to donate their bodies to science.