The Story Of The First Asian-American Woman Elected To Congress

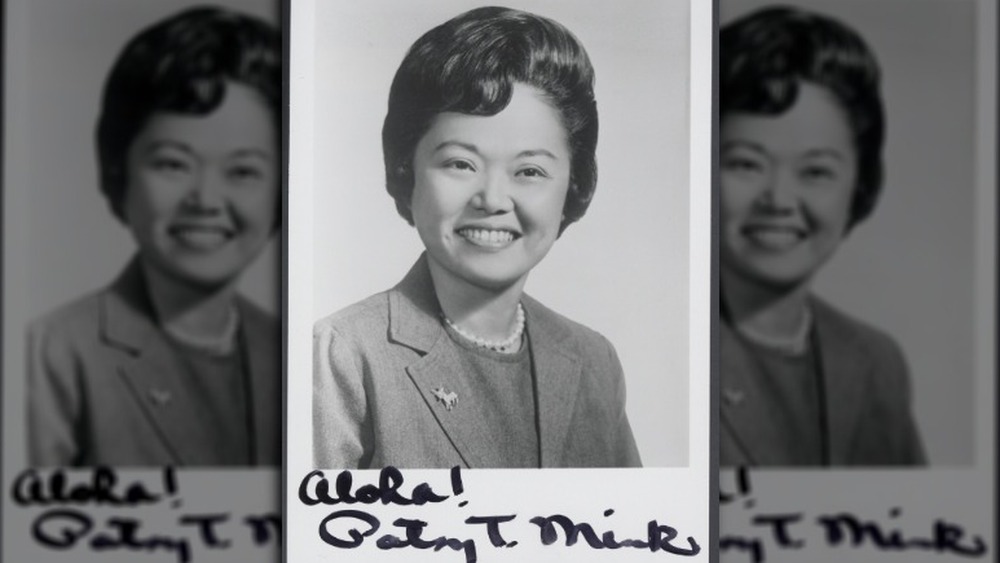

In 1964, history was made when Patsy T. Mink won one of Hawaii's seats in the United States House of Representatives. Her win made her a woman of many firsts, including the first Asian American woman and the first woman of color to be elected to Congress. Only a few years after the island territory had been annexed as a state, the young, punchy lawyer made her way into national politics with an unapologetic agenda focused on breaking down barriers for women, children, immigrants, and minorities.

While she is most famous for championing the landmark law against gender discrimination in federally funded education, Title IX, the trailblazing politician has had a long history of overcoming discrimination and fighting for marginalized communities, both in Hawaii and on the national stage. From her days protesting segregated housing policies at the University of Nebraska to her brief stint as a presidential candidate in the 1972 election, here is the story of the first Asian American woman elected to Congress, Patsy Takemoto Mink.

The sansei from Maui

Hailing from Maui, Patsy Takemoto Mink was born to second-generation Japanese Americans, making her a sansei, or "third-generation ethnic Japanese," as described in the Asian-Pacific Law & Policy Journal. Growing up on the figurative edge of both the Japanese and white American community, Mink saw from an early age the "lines of class, race, and social status." Her father was the first Japanese American to graduate with a civil engineering degree from the University of Hawaii in 1922, his job affording them a comfortable home on two acres of land as opposed to the plantation worker camps where most in their ethnic community resided. Their family spoke English at home, and her upbringing was devoid of the "confining role assigned to females of Japanese descent in that area," with her parents encouraging "her to be strong and assertive."

Despite her family's relative privilege, their proximity to the white American community emphasized the discrimination nonwhites faced. As the only Japanese American on his company's all-white staff, Mink's father was regularly passed over for promotions that were given instead to younger, less experienced white engineers. In the fourth grade, Mink and her brother transferred to Kaunoa English Standard School, an institution where 95% of the students and 100% of the teachers were white because of a de facto segregation policy that required perfect use of English to attend. While the Takemoto siblings passed the admission test easily, they "found the new school environment intimidating and unfriendly."

A teenage Patsy Mink wins her first election

Patsy Mink never dreamed of being a politician as a young girl, but she did end up running for student body president her senior year at Maui High School, according to Esther K. Arinaga and Rene E. Ojiri for the Asian-Pacific Law & Policy Journal. It would be her first election and one that she won, setting a precedent for her future before she even realized where it was heading. In remembering that decision, she said, "Like most of the decisions I've made in politics, it seemed like a good idea at that time. Why not? The football team backed me, that's why I won."

What made her win particularly noteworthy was that it occurred during World War II, when anti-Japanese sentiment was rampant and Japanese Americans were being rounded up into internment camps on the mainland. Mink was a sophomore when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941. While only 1,500 Japanese were interned in Hawaii as opposed to the 120,000 in the continental U.S., the Japanese on these islands felt a deep "fear and shame" over being "identified with the enemy," leading to a tragic self-destruction of their culture and community. Mink's popularity as student body president and achievements as valedictorian during a time when anti-Japanese attitudes raged is a testament to her strength and character.

Fighting segregation at the University of Nebraska

As told by Esther K. Arinaga and Rene E. Ojiri, after spending two years at the University of Hawaii, Patsy Mink discovered that many of her friends were transferring to schools in the continental U.S. Never one to be left behind, Mink started applying to schools on the mainland. Her first stop was Wilson College, a small women's college in Pennsylvania. After a long spiel by the president, who assumed his new student barely spoke English, Mink started in fall 1946 but hated it so much she transferred to the University of Nebraska after just one semester.

At Nebraska, she was able to score housing at International House despite the sudden transfer but was soon furious to find out about the university's segregated housing policies. While International House was labeled as a space for foreign students, in actuality it was the designated housing for any students who weren't white, both foreign and American. "Only white students were permitted to live in the school's dormitories and in the fraternity and sorority houses."

In what would be her first formal campaign against injustice, Mink began protesting segregation through letter writing, speeches, and other grassroots efforts. With support from other students, she was elected "president of the Unaffiliated Students of the University of Nebraska, a 'separate' student government for those who did not belong to fraternities, sororities, and regular dormitories." That same year, the board of regents got rid of the segregation policy.

How discrimination changed her career path multiple times

A huge advocate against discrimination, Patsy Mink had her own experiences with being treated unfairly as a woman of color.

Mink's dream since she was little wasn't politics but medicine. When she applied to several medical schools in 1948, though, she was rejected by all of them. This was despite her stellar grades and extracurriculars, including being president of the Pre-Medical Students Club, as described in the Asian-Pacific Law & Policy Journal. Her rejection was due to the low admittance rate for women (only 2-3% of entering classes were women), as well as high competition from war veterans returning to school.

With her chance to be a doctor gone, she turned to law. Mink was accepted by the University of Chicago Law School under their "foreign student quota" (despite being American) and as one of two women in 1948. In 1952, she returned to Hawaii from Chicago with her law degree, as well as a new husband and daughter. Fully planning to be a lawyer in her home state, she was shocked to find herself ineligible to take the Hawaii bar exam because a law made her a resident of her husband's home state of Pennsylvania, according to April Magazine. Fighting that archaic statute and winning, she passed the exam in 1953. Even then, though, no law firm in the state would hire her because she was a mother and because of her interracial marriage, as told by the New York Historical Society.

Patsy Mink was involved in a non-consensual experiment while pregnant

As described in the Asian-Pacific Law & Policy Journal, when she was at the University of Chicago in 1951, Patsy Mink became pregnant with her only child. Visiting the university's Lying-In Hospital, she (and others) received "vitamins" as part of their prenatal care. For nearly 25 years, Mink thought nothing of it. In 1976, though, she was notified that what she had actually been given was diethylstilbestrol, or DES. The drug was given to patients between 1950 and 1952 at the hospital as part of a "double blind study to determine the value of DES in preventing miscarriages," says Justia. In a move that showed just how little women's autonomy was valued at the time, none of the pregnant women were told the drug was DES nor that they were part of an experiment.

According to The University of Chicago Magazine, DES was later discovered to put the women and their "children at risk for genital abnormalities, fertility and pregnancy problems, and cancer," with the link to cancer being known as early as 1971. Despite this, it took the university four to five years before they reached out by letter to the women involved in the experiment. Mink brought a class-action lawsuit against the university and the Eli Lilly Company, which was settled with terms demanding that all the "women and their DES-affected children receive free lifetime diagnostic testing at the University of Chicago Lying-In Clinic, and treatment if needed."

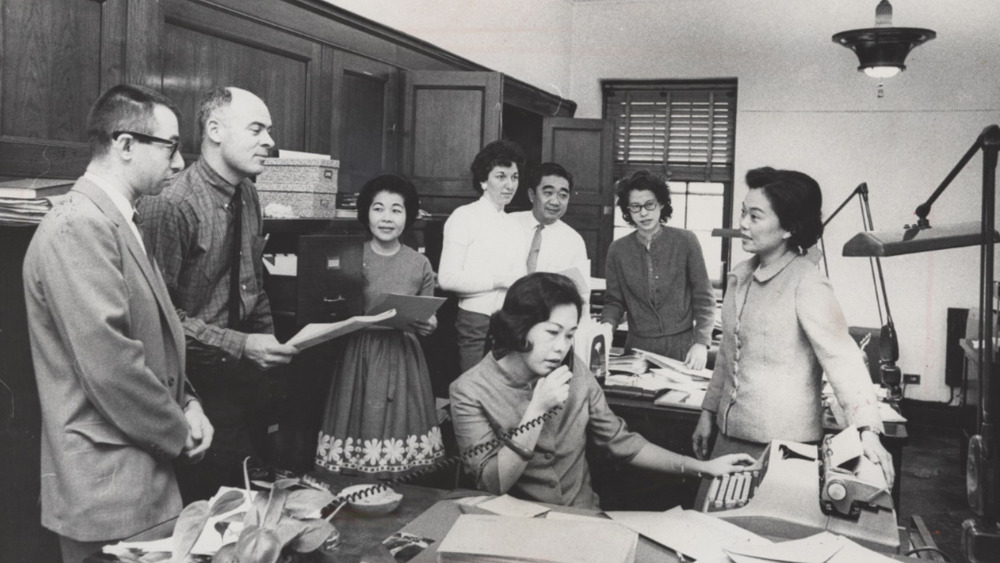

Hawaii's first Japanese American female lawyer joins politics

With no law firm hiring her, Patsy Mink decided to open up her own practice in downtown Honolulu, becoming the first Japanese-American female lawyer in Hawaii, according to Esther K. Arinaga and Rene E. Ojiri. Unfortunately, she struggled to grow her client base and had to look in other spaces for income, including lecturing at the University of Hawaii and taking court-appointed cases that "established law firms traditionally avoided: criminal, divorce, and adoption cases."

Ironically, the slow pace of her work actually allowed Mink to turn her attention towards politics. Spurred on by an invite to meetings on the Democratic party's platform reform, the lawyer quickly became involved, from founding the Oahu Young Democrats in 1954, as mentioned by the National Women's History Museum, to drafting statutes as a staff attorney for the territory of Hawaii's House of Representatives in 1955.

With a better understanding of the workings of that legislative body, Mink ran for and won a seat in the territorial House in 1956, becoming "the first Japanese-American woman elected to the territorial legislature." In 1958, after her first term in the House, she decided against a reelection campaign and ran for a seat in the territorial Senate instead, a move that shocked the Democratic party and signaled her willingness to thwart party expectations. Mink won by a landslide despite the lack of party support, serving in the territorial Senate until 1959, the year that Hawaii became a state.

Patsy Mink's historic win to Congress

According to the U.S. House of Representatives, when Hawaii was annexed in 1959, Patsy Mink was eager to fill the new state's singular seat in the House and started campaigning immediately. As described in the Asian-Pacific Law & Policy Journal, though, she was soon pushed out by Daniel Inouye who had stronger party support and a reputation as a WWII hero. Mink would attribute the lack of support she was getting from the party "to her unwillingness to allow the party to influence her political agenda." Disappointed with her loss in the 1959 election, the politician went back to practicing law for a short while.

By 1962, Mink had returned to public office after winning a seat in Hawaii's state Senate and began resetting her sights on a federal position. Two years later, when she won one of the seats in the U.S. House of Representatives, she became the first woman from the state of Hawaii, the first woman of color, and the first Asian-American woman to be elected to Congress. With a big focus on fighting for issues regarding children and minorities, including ethnic minorities, women, and immigrants, Mink would serve in that position from 1965 to 1977, at which point she ran for the Senate. While she lost that nomination, she would continue to hold public office both nationally and in a state capacity until once again being elected to the House of Representatives from 1990 until her death in 2002.

Patsy Mink's bold opposition of a Supreme Court nominee

A champion of women's issues her entire life, Patsy Mink never shied away from calling out discrimination. According to The Atlantic, when George Harrold Carswell was nominated as Supreme Court Justice by Richard Nixon in 1970, Mink was the first to testify against him, telling the panel, "I am here to testify against his confirmation on the grounds that his appointment constitutes an affront to the women of America."

The basis of her argument was regarding a discrimination lawsuit, in which Ida Phillips had been rejected a position because of her status as a mother, which Carswell had denied to hear the year before. To Mink, his rejection to rule on a case that could have strengthened the fight against sex-based discrimination was a clear sign that having his vote on the Supreme Court would mean having "a vote against the right of women to be treated equally and fairly under the law," as quoted by Honolulu Civil Beat. According to her daughter, Gwendolyn Mink (via The Atlantic), her testimony would mark the first time that sexism or misogyny was cited as a reason to refuse the nomination of a Supreme Court justice.

Her efforts, along with the testimony of others including Betty Friedan, would contribute to Carswell losing out on the appointment and, ultimately, lead to Nixon successfully appointing Harry Blackmun, the writer of the Supreme Court's majority opinion in the case that would legalize abortion, Roe v. Wade.

Patsy Mink for president

In an unprecedented move, Patsy Mink became the first Asian-American Democrat and one of the first women to run for president when she agreed to enter the Oregon presidential primary of 1972, as told by TIME and ThoughtCo. While she had little expectations of actually winning the Democratic nomination, Mink embarked on this campaign in order to bring to the national stage her views "on the Vietnam War, the cutbacks in social programs, and the Nixon presidency," as described by Esther K. Arinaga and Rene E. Ojiri. Additionally, according to the Library of Congress, as a staunch supporter of women's equality, she wanted to challenge the notion that women couldn't be president. In her efforts, Mink was also in contact with Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm, who also ran that year as the first Black American and woman to seek the Democratic nomination, and the two would discuss "how to avoid competing with each other," as reported by Honolulu Civil Beat.

Running as an antiwar candidate, Mink won over "five thousand votes in the Oregon primary on May 23 and smaller numbers in Maryland (573) and Wisconsin (913), where selecting officials placed her name on the ballot" but ultimately withdrew before the 1972 Democratic National Convention.

The mother of Title IX

It would be wrong to tell the story of Patsy Mink without mentioning her monumental role in the pursuit of gender equality. Arguably, Mink's biggest legacy is as the coauthor and champion of Title IX, which barred discrimination based on gender by educational institutions that received federal funding. Signed into law in 1972, the law covered discrimination in "recruitment and admission policies, financial aid, pregnancy, housing, and athletics," as explained by Esther K. Arinaga and Rene E. Ojiri.

While Title IX is most famous these days for its effect on women's sports, it is also notably responsible for the rise of women attending medical school, a result particularly personal to Mink, who was memorably rejected by several medical schools when she was a student. More than 40 years later, around 50.5% of all medical school students are women according to the AAMC, a milestone reached in 2019 that is a far cry from the 2-3% of Mink's day.

As someone who had always seen women's rights and equality as a critical issue, Mink saw Title IX as one of her greatest accomplishments, as told by The Atlantic. On the 25th anniversary of its passing, Mink touched on the importance of the law. "The pursuit of Title IX and its enforcement has been a personal crusade for me. Equal educational opportunities for women and girls is essential for us to achieve parity in all aspects of our society."

How a lawsuit by Patsy Mink inadvertently led to Nixon's impeachment

An outspoken critic of the Nixon presidency, Patsy Mink would describe "her challenge to government secrecy as her most satisfying accomplishment" during this time, according to the Asian-Pacific Law & Policy Journal. Her significant contribution was in 1971 when she sought to halt a nuclear testing project that was scheduled to occur in the Pacific, which she feared would cause a tsunami that would affect Hawaii. In her efforts, she discovered that several government agencies had criticized the project and asked to see their reports but was refused by the president, exercising the right to keep secrets "in the interest of national defense or foreign policy." In retaliation, Mink filed a suit demanding the release of those papers under the Freedom of Information Act.

Mink v. Environmental Protection Agency would make its way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Unfortunately, the long process meant that the nuclear testing occurred without incident and, in the end, the court maintained that the documents did not have to be disclosed. However, in a decision that would allow Congress to strengthen the Freedom of Information Act, the Court did suggest that new guidelines could be added that would "permit judicial review of the executive's actions." Even more, in a sort of twisted fate, the Mink v. EPA case would later be "cited to justify releasing President Richard Nixon's secret Watergate tapes," ultimately leading to his impeachment, as worded by Honolulu Civil Beat.

Posthumous honors

Patsy Mink died in 2002 after more than 40 years of serving in public office. Shortly after her death, Title IX, behind which Mink had been such a powerful force in its creation and passing, was renamed in her honor as The Patsy Mink Equal Opportunity in Education Act, according to the United States Courts. In 2014, she was once again honored posthumously for her lifelong contributions with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, as reported by Hawaii Magazine. Leading the efforts to have her awarded with the medal was Hawaii law professor Troy Andrade, who pointed out one of her iconic speeches to The Atlantic, "It is easy enough to vote right and be consistently with the majority. But it is more often more important to be ahead of the majority, and this means being willing to cut the first furrow in the ground and stand alone for a while if necessary."

That exact quote can be found at the site of a bronze statue of Mink that was dedicated on what would have been her 91st birthday in 2018 at the Hawaii State Public Library, according to Honolulu Civil Beat and the Hawai'i State Foundation on Culture and the Arts. The statue serves as a way for the community of her home state to "properly honor her memory and to utilize her example as an inspiration for current and future generations."