The Untold Truth Of Creedence Clearwater Revival

Creedence Clearwater Revival, or CCR, as it's often abbreviated, is one of the all-time great American rock 'n' roll bands. They were a little bit '50s-style rock, a little roots rock, and a whole lot of Americana, all the while rocking hard with a straight-out-of-Louisiana sound referred to as "swamp rock." A popular band for a scant four years, Creedence Clearwater Revival churned out seven albums and a staggering stream of hits, near-perfect, often-covered songs that will likely never leave classic rock radio playlists, including "Green River," "Suzie Q," "Proud Mary," "Born on the Bayou," "Bad Moon Rising," "Lodi," "Down on the Corner," "Fortunate Son," and "Have You Ever Seen the Rain." It's no overstatement to say that Creedence soundtracked the formative years of the Baby Boomer generation as well as the counterculture movement.

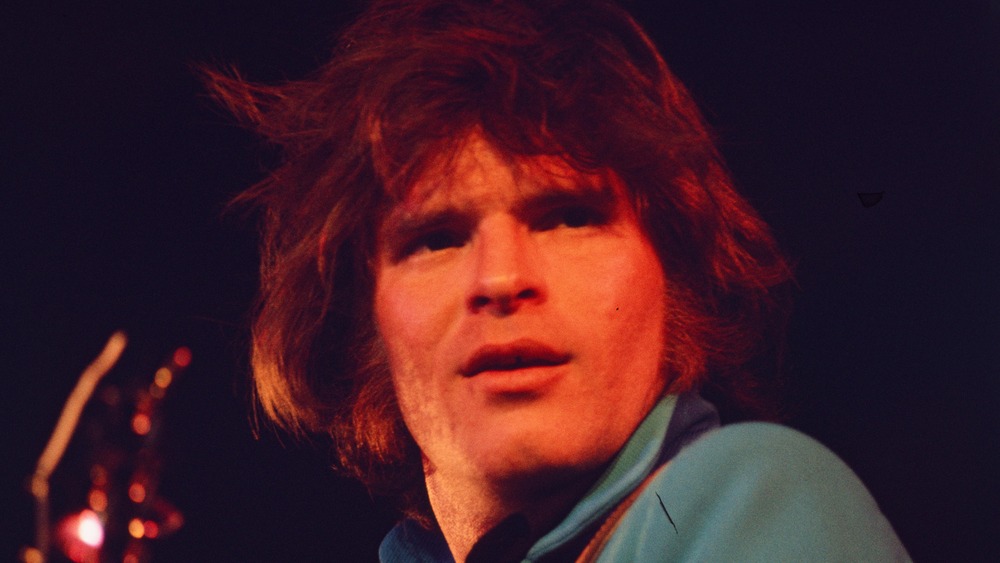

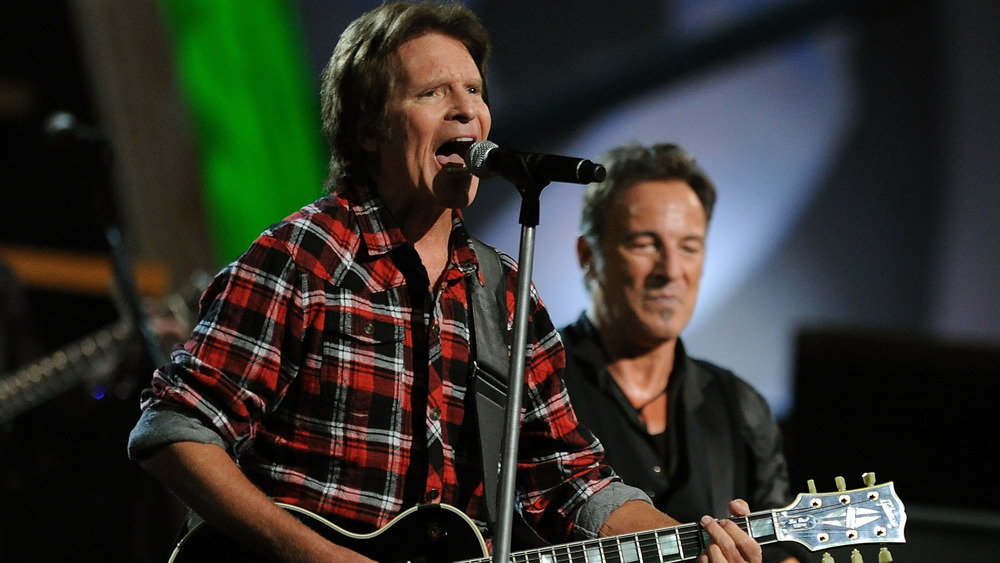

Led by the howling vocals of John Fogerty, who also wrote most of the band's timeless songs, CCR sold more than 28 million albums and split up in 1972, never to officially reunite. Here's the inside story of Creedence Clearwater Revival.

Creedence Clearwater Revival formed when two brothers joined forces

Creedence Clearwater Revival was almost entirely a vehicle for the singing, songwriting, and guitar-playing of John Fogerty, but the band can trace its origins to groups formed by a different member of the family: John's older brother, Tom Fogerty. In the 1950s, high schooler Tom Fogerty formed a band called Spider Webb & the Insects. According to AllMusic, the group signed a deal with Del-Fi Records but never actually recorded anything and broke up in 1959.

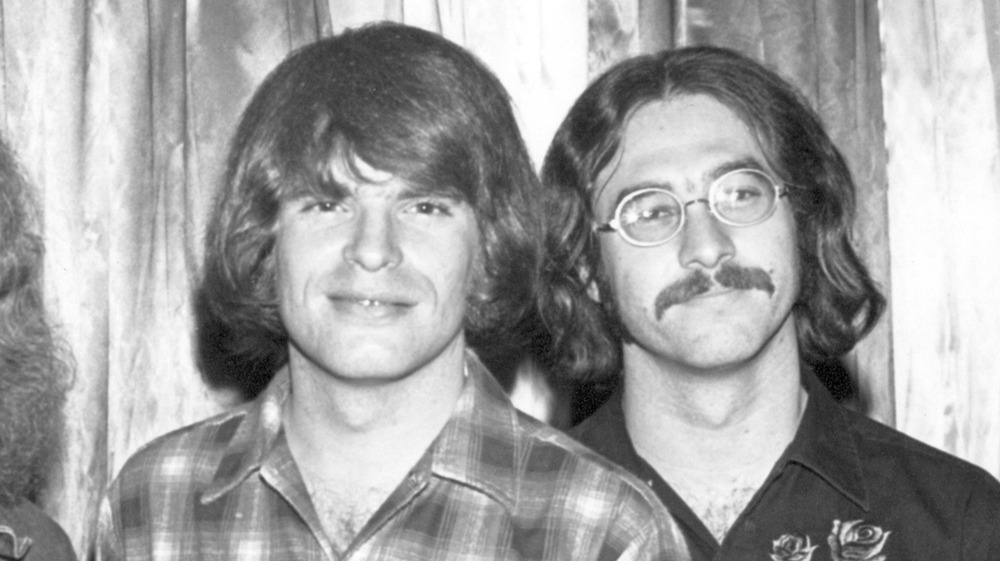

Meanwhile, John Fogerty had formed his own group, the Blue Velvets, along with bassist Stu Cook and drummer Doug Clifford. While still fronting Spider Webb & the Insects, Tom Fogerty would occasionally play gigs with the Blue Velvets, but after his primary band split, the Blue Velvets officially absorbed Tom Fogerty, and he became the lead singer of the band, rebranded Tommy Fogerty & the Blue Velvets. This iteration recorded a handful of singles in 1961 and 1962, printed in very small runs and which didn't bring the band any success. By the mid-1960s, and after changing its name once more to the Golliwogs, the foursome of two Fogertys, Cook, and Clifford had released six singles, all of them co-written by John and Tom, who also split vocal duties. By the time the group would reach its final stage, as Creedence Clearwater Revival, Tom Fogerty's vocal and songwriting contributions had diminished to the point of virtual nonexistence.

How CCR got its very unique name

When John Fogerty and his swamp-rocking cohorts came up in the 1960s, it was more fashionable for the mainstream bands to have short and direct names, monikers like the Who, the Rolling Stones, and the Kinks. A name like "Creedence Clearwater Revival" would suggest that the band would sound like similarly grandly named psychedelic groups such as Jefferson Airplane or the 13th Floor Elevators. Those three words just sound like they belong together, so they must have some kind of unifying meaning, right? Not really.

When the band signed to Fantasy Records, it was still called the Golliwogs, which label head Saul Zaentz loathed. "It was ridiculous — a stupid name," he said in the CCR bio Bad Moon Rising. To generate a new name, Zaentz came up with a list of ten ideas and then sent the band off to do the same, after which they'd find one they agreed on. Some early contenders: Deep Bottle Blue, Muddy Rabbit, and Credence Nuball and the Ruby. The latter was suggested by guitarist Tom Fogerty, based on the name of a friend.

The rest of the Golliwogs went to work improving on Fogerty's idea, adding an extra "e" to get "Creedence" and then adding "Clearwater," taken from an ad for Olympia Beer purporting that the product contained "cool, clear water." Then frontman John Fogerty added "Revival" because he felt like the band was getting a new lease on life with its record deal.

Creedence Clearwater Revival wasn't exactly born on the bayou

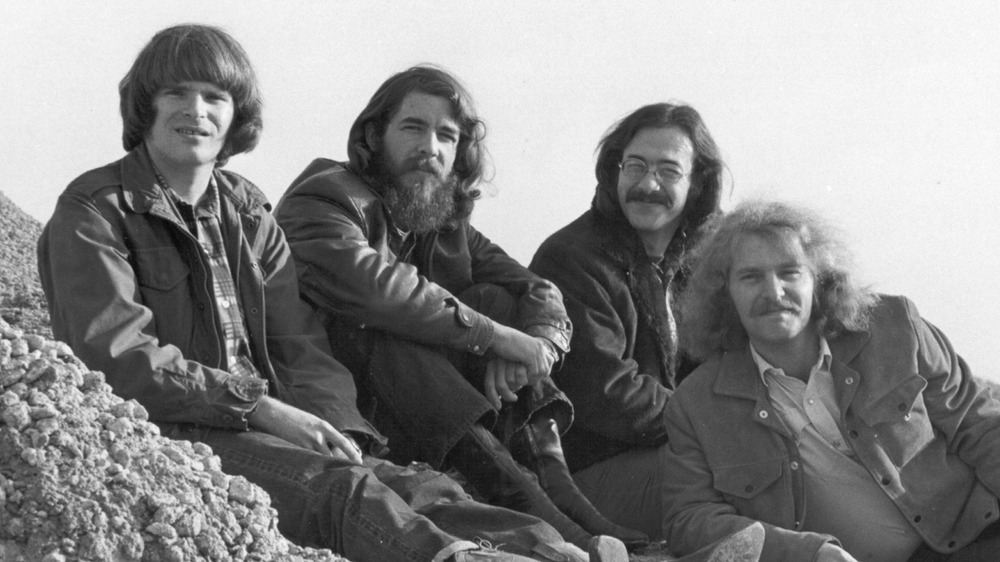

Creedence Clearwater Revival's sound, a mixture of grimy hard rock, blues, folk, and Gulf Coast styles, has a name: "swamp rock," because it sounds like the band comes straight out of Louisiana, particularly Southern-drawling lead singer John Fogerty. That Louisiana flavor (and bayou accent) is all over Creedence's songs, explicitly so on the song "Born on the Bayou." But Fogerty is singing from the point of view of a character, because neither he nor anyone else in Creedence Clearwater Revival was born (or raised) anywhere near the American Southeast.

According to AllMusic, John and Tom Fogerty both hail from the Berkeley area of California. Drummer Doug Clifford was born in nearby Palo Alto, per IMDb, and bassist Stu Cook is from Oakland. The band members knew each other because they'd all attended El Cerrito High School, per John Fogerty's Fortunate Son.

Here's another CCR geographical anomaly. "Green River" isn't about an actual Green River, one in Louisiana or elsewhere. The inspiration "was actually called Putah Creek by Winters, California," John Fogerty told Rolling Stone. "It wasn't called Green River, but in my mind I always sort of called it Green River."

John Fogerty pulled from everywhere to write "Bad Moon Rising"

In 1969, Creedence Clearwater Revival went to #2 on the Billboard Hot 100 with "Bad Moon Rising," a jaunty number full of cryptic lyrics about earthquakes, hurricanes, and unsettling objects in the night sky. CCR frontman John Fogerty was uniquely inspired by The Devil and Daniel Webster, a 1941 film adaptation of the classic short story of the same name by Stephen Vincent Benét, in which a farmer sells his soul to the Devil and then gets out of the contract by hiring famed 19th-century lawyer Daniel Webster to defend him. "There's one great scene where there's a huge storm, and the neighbor's corn crop was completely knocked down. But next door, the Devil and Daniel Webster are standing side by side, looking out the barn door. You can see Daniel Webster's corn still standing tall in a straight row, six feet high. The contrast represented a very strong image to me," Fogerty said in Bad Moon Rising. "Scary, spooky stuff." That led to all the song's catastrophic imagery. "It was about the apocalypse that was going to be visited upon us," Fogerty said to Rolling Stone (via Ultimate Classic Rock) in 1993.

As for the music, Fogerty wrote in his memoir Fortunate Son that the guitar riff on "Bad Moon Rising" was "certainly borrowed from the Scotty Moore guitar lick on the Elvis [Presley] record "I'm Left, You're Right, She's Gone."

Why CCR's Woodstock performance was mostly forgotten

Part of the reason why the Woodstock Music Festival in 1969 was such a monumental event, a definitive cultural gathering of the Baby Boomer generation, was because nearly every major rock act of the era took the stage over the course of the weekend. Among the bands who played for an audience of 400,000 people (per History): Santana, Jefferson Airplane, Jimi Hendrix, the Who, Sly and the Family Stone, and Joe Cocker. All those acts were prominently featured in the Woodstock documentary and its live-recorded soundtrack, which helped solidify the importance of the event in the collective consciousness. Creedence Clearwater Revival also played the festival, but the band's presence there has often been forgotten and overlooked, according to the Chicago Tribune. Ironically, Woodstock may not have become a concert of great magnitude without Creedence — once the chart-topping band agreed to be a headliner, a slew of other acts signed up, too.

The reason why Creedence's Woodstock set is lost to history is because it wasn't initially or conclusively preserved, left out of the Woodstock documentary and soundtrack record at the behest of frontman John Fogerty. "By the time we went on it was 2:30 in the morning," he told the Los Angeles Times. "We played a great set, but there was almost no reaction," he added, meaning the crowd was asleep and unreceptive, which made for a performance that Fogerty wasn't keen to let people not at Woodstock witness.

Creedence Clearwater Revival is the all-time #2 band

When one thinks about the top-selling and most successful musicians of all time, names like "the Beatles," "Elvis Presley," and "Michael Jackson" likely come to mind. Indeed, all those acts scored at least a dozen #1 hits each (per Insider) and rank at or near the top of the Recording Industry Association of America's list of musicians who sold the most albums. Perhaps because their time in the spotlight was a relatively brief four years, or because they're so explicitly associated with the late '60s and early '70s sound, Creedence Clearwater Revival can be overlooked when discussing the pantheon of pop-rock superstars. However, in 1970, according to ChartMasters, the best-selling band on the planet was Creedence Clearwater Revival, which moved more LPs than heavyweights like the Beatles and Led Zeppelin.

Creedence Clearwater Revival is also the holder of an impressive (but also mildly dubious) chart record. According to Slate, the group hit #2 on the Billboard Hot 100 five times. (Those almost chart-toppers: "Proud Mary," "Green River," "Bad Moon Rising," "Travelin' Band," and "Lookin' Out My Back Door.") That's the all-time most #2s ... for an act that never also hit #1.

John Fogerty got sued over a big Creedence hit

In 1970, Creedence Clearwater Revival's John Fogerty-written "Travelin' Band" was a smash hit, peaking at (of course), #2 on the Billboard Hot 100 (per Slate). It was more of what CCR did best: hard rock with wailing vocals laced with elements of Southeastern U.S. folk styles, a bridge between the straightforward rock of the '50s and the heavy metal that would come of age in the '70s. Fogerty had a deep appreciation of and was extremely influenced by the old-time rock 'n' roll performed by Southern musicians. "Little Richard was the greatest rock & roll singer of all time," he told Rolling Stone. "I was a kid when his records were coming out, so I got to experience them in real time."

Unfortunately, according to Forbes, Little Richard was paid the egregiously low sum of $50 by Art Rupe's Specialty Records for the rights to those rock 'n' roll blueprint songs like "Tutti Frutti" and "Good Golly Miss Molly." And unfortunately for Creedence Clearwater Revival, Specialty took the band to court in October 1971, alleging that CCR's Little Richard-inspired "Travelin' Band" was more like a Little Richard ripoff, specifically of "Good Golly, Miss Molly" (via WKLH-FM). In the end, Specialty eventually dropped the case.

The end of Creedence Clearwater Revival

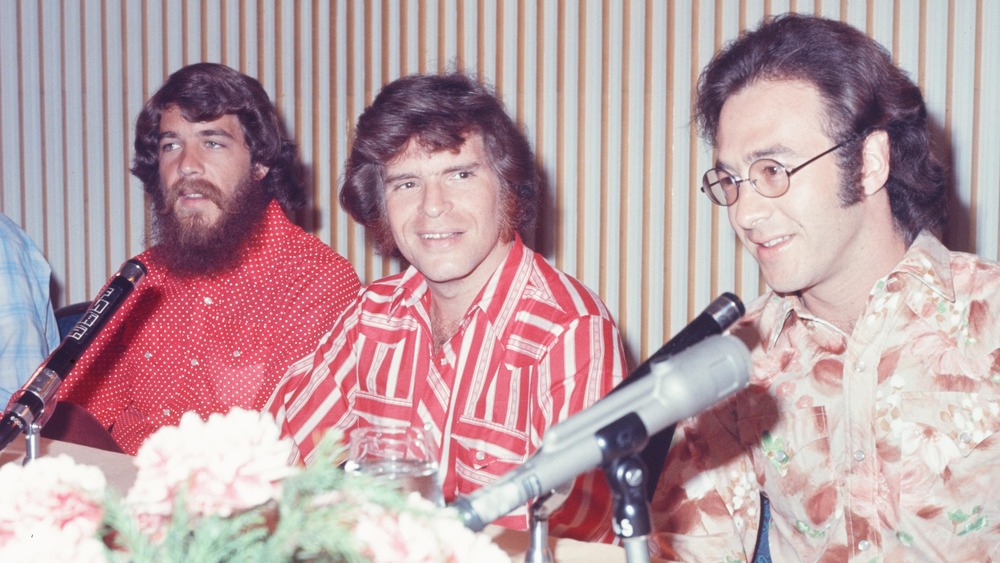

Of the original members of Creedence Clearwater Revival who have had solo careers, John Fogerty — the group's lead singer and chief songwriter — has been the most successful, scoring hit singles like "Jambalaya (On the Bayou)," "The Old Man Down the Road," and "Centerfield," a baseball stadium standard. But he wasn't the first member of the extremely successful CCR to leave the band to go it alone — that would be rhythm guitarist, and his brother, Tom Fogerty. According to Ultimate Classic Rock, John's tight and unrelenting creative control over the band lead to Tom's exit. After recording the album Pendulum, Tom Fogerty departed Creedence in 1971 and, over the next ten years, released five solo albums that didn't sell very well or yield any hit singles.

Meanwhile, back in the depleted Creedence Clearwater Revival, John Fogerty took his brother's motivations to heart and let the other two band members, Stu Cook and Doug Clifford, write and sing the majority of songs on the next album, Mardi Gras. Unlike the group's previous albums, Mardi Gras didn't go platinum. After one final tour as a three-man band, Creedence split up in 1972.

An ill-fated Creedence Clearwater Revival revival

After Creedence Clearwater Revival split up professionally, they diverted personally, too, and bitterly at that. According to The Hollywood Reporter, John Fogerty loathed and resented Fantasy Records and its boss Saul Zaentz for placing him and his bandmates under what he thought were unfair and exploitative contracts. Fogerty's negative feelings spilled over to the rest of the CCR, whom he felt "betrayed" by (as he told Opie Radio) because they'd sold their right to vote on band decisions — and control of the band — to Zaentz.

The freeze-out continued for years, and the band reunited as Creedence Clearwater Revival just once, but not in a professional setting to record music or play for fans: The four members performed together in 1980, at Tom Fogerty's wedding, according to AllMusic. Fogerty died in 1990, and several years later, CCR members Doug Clifford and Stu Cook teamed up to hit the road as Creedence Clearwater Revisited. According to The Times-Picayune, John Fogerty sued the duo in 1996 because he controlled the rights to the name "Creedence Clearwater Revival" and didn't authorize this use. In 2001, the sides reached an agreement: Clifford and Cook would pay Fogerty a royalty anytime they used the "Revisited" name. They paid that fee up until 2011, when Fogerty violated the terms of the settlement by disparaging the latter-day Creedence variant in interviews.

John Fogerty wouldn't get the band back together

In the midst of all the tragedy and legal battling that descended on the world of Creedence Clearwater Revival in the 1990s, the surviving members of the band were given more than one opportunity to leave the past in the past, get back together, and play their beloved songs for a large and appreciative crowd. John Fogerty personally prevented both CCR reunion gigs from happening. After Bill Clinton became the first member of the Baby Boomer generation to be elected president of the United States, organizers of his inauguration celebration approached the members of Creedence Clearwater Revival about performing at the January 1993 event. Fogerty gave a hard pass. "I said, 'I'm not playing as a band with Creedence. I don't play with those guys. We will never play as a band again,'" Fogerty wrote in his memoir Fortunate Son (via Rolling Stone).

Later in 1993, the three living members of CCR at least breathed the same air together when the group was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. It's customary for newly enshrined acts to perform, even if they've broken up, so Fogerty took the stage ... with Robbie Robertson and Bruce Springsteen. He'd arranged to prevent Cook and Clifford from joining him.

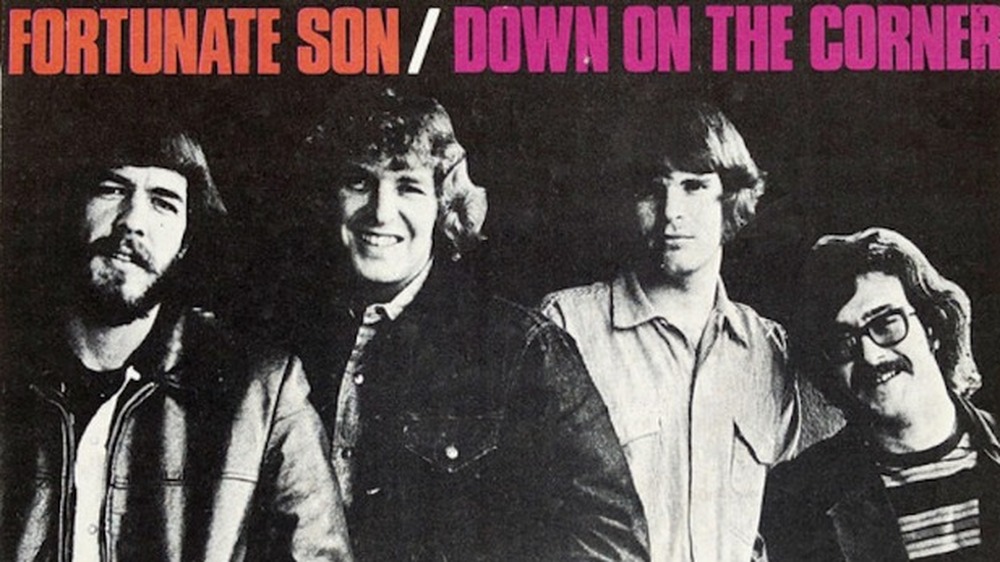

Why "Fortunate Son" is in so many Vietnam War movies

Since the 1980s and 1990s, when Hollywood ramped up its examination and depictions of the Vietnam War, filmmakers have frequently used a particular trick to let audiences know that a scene takes place in the Southeastern Asian country, during that bloody military conflict, and in the late 1960s: The soundtrack blares Creedence Clearwater Revival's "Fortunate Son."

According to Military.com, CCR's John Fogerty wrote the song in 1969 as a protest against the Vietnam War, calling out the offspring of the connected and wealthy who could pull some strings to get a "draft deferment" and avoid dangerous combat duty. That sentiment is made pretty clear in the song, which means it can instantly convey to audiences that the filmmaker's point of view is decidedly (and retroactively) anti-war. "Fortunate Son" has been used to score Vietnam War-focused (or just '60s-set) sequences in movies like Forrest Gump, Moonwalkers, Prefontaine, numerous documentaries about the era, and on the TV shows Family Guy and American Dad! – to make fun of Vietnam War movie clichés. And that doesn't even include the '60s-centric or Vietnam War films that use other Creedence Clearwater Revival songs.