Broadway Shows That Closed Before Opening Night

Mounting a Broadway show is a long, expensive, and work-intensive process. It takes years to get a show ready, and even before it officially opens for top-price tickets and to welcome in critics and writers to review it, producers, cast, and crew might work out the kinks and test reactions with a trial run outside of New York or actually play a few nights in its Broadway theater home in the form of "previews." This refers to a show that is not quite locked into its final presentation, with major elements of the show still in flux or subject to change.

Sometimes, while trying to fix stuff in previews, either in New York or beforehand, the makers of a Broadway musical or play will realize that their show is too much of a disaster to fix, and they'll shutter the show, technically before it ever "officially" opens. Here are some productions that were all set to run on Broadway for years and years but shut down before their scheduled official debut.

Annie 2: Miss Hannigan's Revenge

While movie sequels and TV series revivals are extremely common, Broadway musical continuations just don't seem to fly. Perhaps it's because sequels require its audiences to have an intimate knowledge and understanding of the predecessor, and that isn't guaranteed on Broadway, where the first musical may have run years earlier and its details (or appeal) obscured by the passage of time.

Despite colossal failures like Bring Back Birdie and The Best Little Whorehouse Goes Public (sequels to Bye Bye Birdie and The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas, respectively), producers couldn't resist a follow-up to Annie, the long-running 1970s Broadway smash about a plucky redheaded parentless kid who thwarts cruel orphanage mistress Miss Hannigan and gets herself adopted by the kindly Daddy Warbucks.

According to The New York Times, producers sunk $7 million into Annie 2: Miss Hannigan's Revenge and started rehearsals in November 1989. To both earn back some of that money and also get the show in tip-top Broadway shape, Annie 2 premiered in Washington, D.C., and critics savaged it. In January 1990 (per The New York Times) producers announced that Annie 2 would not debut in New York anytime soon but would continue on, heavily revised, in a staging in Connecticut. The show, in any form, never did play Broadway.

Truckload

America went through a lot of fads in the 1970s, including the Pet Rock, shag carpeting, and roller disco. But one of the most inexplicable was the trucker craze. Spawned by the boom in popularity of the adoption of big-rig technology like citizens band radios in regular cars to instantly communicate information about good gas prices and availability during the 1970s fuel crisis, America on the whole got into long-haul culture. The C.B. radio-based novelty song "Convoy" topped the pop chart, the trucker show B.J. and the Bear was a TV hit, and Smokey and the Bandit was among many popular trucker movies. This blue collar fascination also drove on up to the Great White Way.

According to The New York Times, Truckload was set to debut in Broadway's Lyceum Theatre in September 1975. Pitched as a "road musical" about "Americans in transit," Truckload boasted a score from Grease arranger Louis St. Louis and a script by Tony Award-winning writer Hugh Wheeler (who also had the perfect name to write a show about vehicles). But despite the right climate and a good pedigree, Truckload flopped. It made it through just six unofficial preview performances before shutting down for good.

Me Jack, You Jill

Two separate shows about putting on a play were set to hit Broadway in the 1975-1976 theatrical season. One of them was A Chorus Line, about dancers auditioning to be part of a big musical, which ultimately ran for more than 6,100 performances and was at one time the longest-running production in Broadway history. The other one was Me Jack, You Jill.

A straight play (meaning non-musical), it featured a cast of just four, including five-decade Broadway veteran Sylvia Sidney, and was a mystery that took place on an empty stage of a theater. It was a play-within-a-play in other words. Critic Ken Mandelbaum was in attendance at one of the show's few preview performances and wrote in his "Broadway Buzz" column that the show "was so bad that the audience began to talk back to the actors." When one of the characters threatened to shut down the fictional play at the center of Me Jack, You Jill, the audience reportedly broke into applause. Press agent Josh Ellis worked on Me Jack, You Jill, which he'd later tell the New York Post was "perhaps the worst play in Broadway history." At least not that many people saw it — Me Jack, You Jill producers cut their losses and shut down the show during previews.

Senator Joe

Sen. Joseph McCarthy's efforts to root out Communists in the highest levels of American politics in the 1950s is one of the ugliest and most contentious moments in American history. He played off of America's fear of Soviet Russia to take down enemies and ruin lives with merely an accusation or suggestion that the person had at least a passing interest in Communism. And in the late 1980s, Tom O'Horgan, who helped bring important shows like Hair and Jesus Christ Superstar to Broadway, thought that the saga of McCarthy would make an excellent musical.

O'Horgan wrote the music for Senator Joe, writes Vulture, while actor and writing newcomer Perry Arthur Kroeger provided a script and lyrics. Billed (per the Chicago Tribune) as "a song cartoon of the '50s as seen through the life and times of Sen. Joseph McCarthy," Senator Joe began rehearsals in October 1988. McCarthy was an alcoholic who died of cirrhosis of the liver caused by years of overconsumption. Senator Joe addressed this element of his life with a musical number (hosted by an actor playing legendary reporter Edward R. Murrow) set in McCarthy's liver — dancers twirled around while dressed as diseased cells.

Senator Joe lasted three preview performances over two days in January 1989, shutting down because producer Adela Holzer couldn't pay the actors. In the weeks after the closure, Holzer told O'Horgan that she'd raised enough money to stage the show again, which didn't happen because she was arrested for grand larceny.

Breakfast at Tiffany's

Breakfast at Tiffany's is a delightful movie, and it became a template for dozens of rom-coms and New York-set movies that followed in its wake. Audrey Hepburn is bubbly and charming as the flaky romantic Holly Golightly, trying to find love and fulfillment in 1960s New York — it was pretty much Sex and the City with the look of Mad Men.

The 1961 film is cute, funny, romantic, and popularized the standard "Moon River." Those sound like excellent ingredients for a hit Broadway musical, except that the creators of the Breakfast at Tiffany's stage endeavor (briefly renamed Holly Golightly) didn't base their work on the movie — they adapted Truman Capote's novella that served as an extremely loose inspiration for the film. According to PopMatters, for example, the book took place in the bleak 1940s (not the 60s), romantic male lead Paul Varjak was gay and also miserable, and Holly never finds her lost cat, a metaphor for her own directionless, open-ended trajectory. Now, imagine all that with singing and dancing and starring TV superstar Mary Tyler Moore as Holly Golightly in her stage debut.

Despite the involvement of Moore, and with a script by Pulitzer Prize- and Tony-winning playwright Edward Albee, Breakfast at Tiffany's closed in previews, a December 1966 opening never happening. (According to the Internet Broadway Database, producer David Merrick opted to shut it down "rather than subject the drama critics and the public to an excruciatingly boring evening."

The Freaking Out of Stephanie Blake

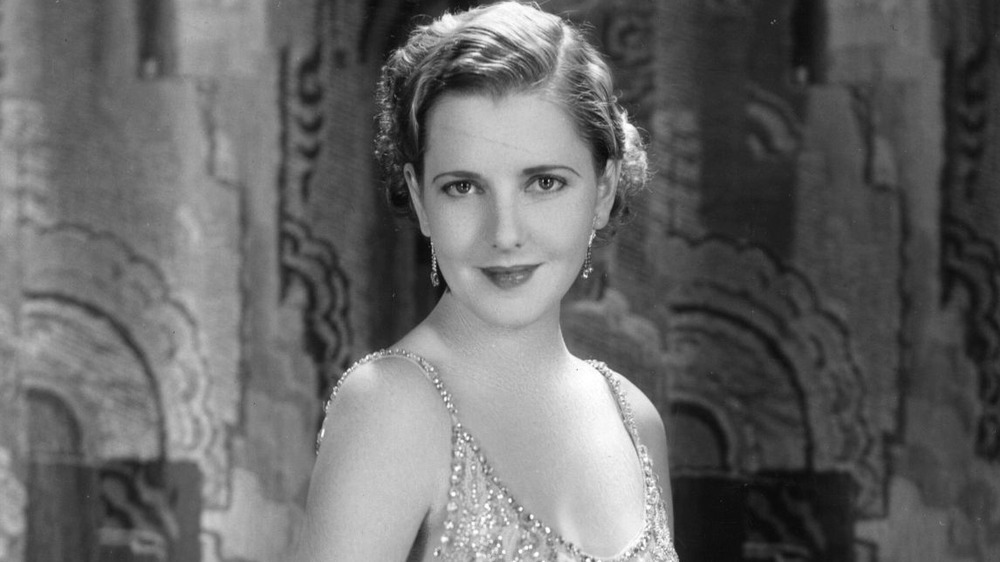

Jean Arthur was best known for her work in 1930s movies like You Can't Take It With You, Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. Arthur also did a lot of theater, notably starring in Peter Pan in 1950, on the cusp of her 50th birthday. It was a major theatrical event then in 1967 when, according to The New York Times, Arthur announced her return to Broadway via the new comedic play, The Freaking Out of Stephanie Blake.

Overseen by prolific and powerful theatrical producer Cheryl Crawford, the show marked the first Broadway gig for playwright Richard Chandler, who happened to be Crawford's assistant. The plot, which reflected the hot-at-the-time and very 60s notion of a "Generation Gap" between older adults and the up-and-coming anti-Vietnam War counterculture movement, concerned an elderly and conservative Midwesterner (Arthur) who takes a trip to New York to see her niece only to learn, to her shock and horror, that the young lady has fallen in with a band of hippies.

Previews of The Freaking Out of Stephanie Blake began in October 1967, per The New York Times, but the official opening was delayed after Arthur collapsed on stage. Crawford floated the idea of calling off the entire show if Arthur was too sick to continue, and that's indeed what happened. The show ran for three preview performances and then disappeared. Arthur, who lived until 1991, never acted again.

Bobbi Boland

According to The New York Times, The Freaking Out of Stephanie Blake was just one of about ten shows about the Generation Gap that debuted in the late 1960s. That doesn't include Bobbi Boland. Depicting the philosophical divide between the Greatest Generation and Baby Boomers and how it came to a head in the Vietnam War era, Bobbi Boland hit theaters way past its period of peak relevance — in 2001. Set in a small Florida town in the late 60s, the action centers on Bobbi, an ex-pageant queen and charm school headmistress grappling with the changing times and relaxing social mores.

The play debuted in March 2001 at New York's tiny ArcLight Theater, and it was so well-received that producer Joyce Johnson planned to move it to the much larger Broadway venue, the Cort Theater, in late 2003, per The New York Times. Starring as Bobbi was 1970s TV sex symbol and Charlie's Angels star Farrah Fawcett, who hadn't done major theater in 20 years. After seven previews, Johnson announced that Bobbi Boland would never open on Broadway. "The vivid characters I saw in a small theater did not transfer to the Cort," she said. "The play simply does not work in a Broadway house." Johnson lost her entire $2 million investment in Bobbi Boland, and Fawcett never did appear in a Broadway play.

The Little Prince and the Aviator

Antoine de Saint-Exupery's 1943 book The Little Prince is a classic work of both children's literature and science fiction. It's a collection of stories about The Prince, a lonely and sensitive little boy from outer space who recollects his adventures to a pilot when both find themselves marooned in the Sahara Desert. The meat of the story and the most exciting happenings involve The Prince's interstellar adventures, but the creators of the Broadway musical adaptation, The Little Prince and the Aviator (including Sweeney Todd writer Hugh Wheeler) decided to significantly up the time and effort devoted to the pilot, a fairly ordinary and mopey guy.

According to the Internet Broadway Database, previews were to begin on Dec. 31, 1981, only to be abruptly rescheduled for days later. Per Ken Mandelbaum's Not Since Carrie, the producer firing the original director and choreographer certainly didn't help the show get off on the right footing. Mandelbaum characterized The Little Prince and the Aviator as "a boring evening of disconnected scenes," on account of how the musical constantly switched between inexplicable flashbacks to events in the life of the pilot (played by Michael York, aka Basil Exposition from Austin Powers) and tales from The Prince (Anthony Rapp of Dazed and Confused and the original Broadway production of Rent). After 20 previews in January 1982, producers closed The Little Prince and the Aviator on the day before it was supposed to officially open, much to the surprise of cast and crew.

Rachael Lily Rosenbloom and Don't You Ever Forget It!

According to Ken Mandelbaum's Not Since Carrie, the 1973 musical Rachael Lily Rosenbloom and Don't You Ever Forget It was intended to be a campy, bawdy, and completely over the top extravaganza, a parody of musicals and a satire of Hollywood and celebrity. It told the story of Rachael Lily Rosenbloom, an actress who worships Barbra Streisand (she takes the "a" Streisand dropped from her first name and added it to hers), on her journey from working at a fish market to gossip columnist to Academy Award winning star of Cobra Goddess on Pink Flamingo Road to nothing.

Produced by Bee Gees manager Robert Stigwood and Atlantic Records founder Ahmet Ertegun, Rachael Lily Rosenbloom sprung from the mind of Paul Jabara, an actor who'd appeared in the original casts of Hair and Jesus Christ Superstar. Jabara wrote the title role for Bette Midler, who passed on the chance, and the part instead went to cabaret singer Ellen Greene in her first Broadway role (years before she'd starred in the movie version of Little Shop of Horrors).

The production was plagued with problems. Tom Eyen was brought in to rewrite the script and replace the fired original director, but he couldn't save the show. After seven preview performances, Rachael Lily Rosenbloom and Don't You Forget It went dark, too arch and too silly for the bright lights and high ticket prices of Broadway.

Let My People Come

In the late 60s and early 1970s, Broadway was rocked by a couple of nudity-containing shows with explicit sexual themes. Influenced by the hippie, countercultural movement, the musical Hair famously included an end-of-show dance party with a naked cast, while the musical vignette collection Oh! Calcutta! included several long scenes with unclothed actors. Let My People Come also involved a lot of frank talk from nude people about sexual behaviors (and simulations thereof) in a series of bits set to music, only it was a lot more explicit.

The names of the most of the songs in the show are too raunchy and direct to print. One tune, a parody of the 1940s standard "Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy" about a man that was really good at performing a particular physical act, got Let My People Come writer Earl Wilson, Jr., sued.

Let My People Come, promoted simply as a "sexual musical," ran for 1,200 performances at the small Village Gate venue in New York's more libertine Greenwich Village before getting the call to jump over to a more visible and lucrative run at Broadway's Morosco Theater. Just before its scheduled opening, Wilson asked producer-director Phil Oesterman to remove his name from the show, because changes the latter made rendered the show "vulgar," he told The New York Times. Let My People Come still opened with previews, and after a whopping 128 of them over three months, the envelope-pushing show closed.

Hangman

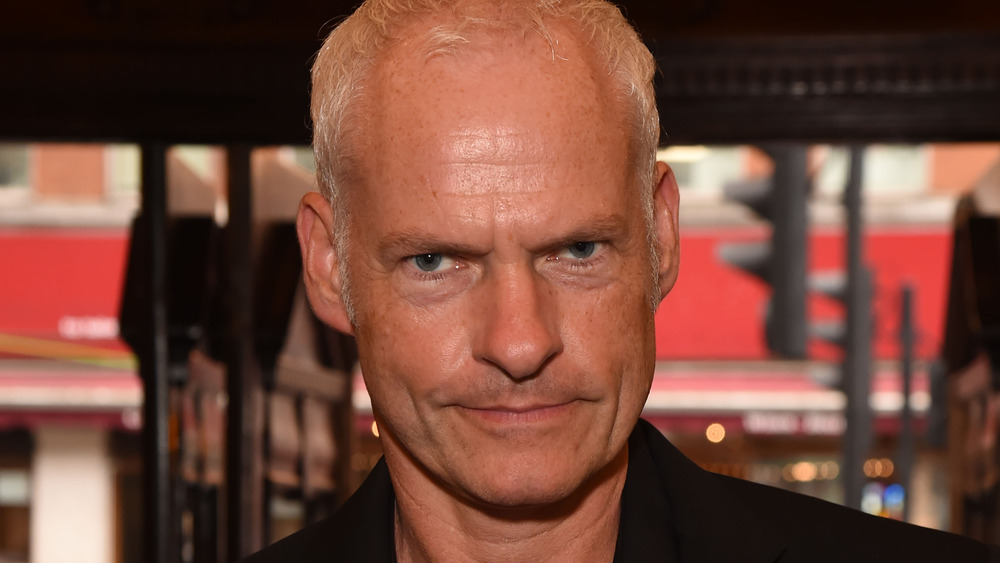

Martin McDonagh is an acclaimed playwright, nominated four times for the Tony Award for Best Play for works like The Beauty Queen of Leenane, The Lonesome West, and The Pillowman. The latter also won him the Olivier Award (the British stage equivalent of the Tony) for Best New Play. Already a favorite of two theatrical scenes, McDonagh's profile with the general public significantly increased in 2018 after he won a Golden Globe and received an Oscar nomination for writing the screenplay for Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri.

That built up hype and demand when in 2019, producers announced through Deadline that his Olivier Award-winning play Hangmen would move to Broadway in 2020 and run for 20 weeks. The comedy, about the abolition of the death penalty in the United Kingdom in the 1960s, would run in previews from late February to mid-March, when it would officially open for business. Some of those preview performances came to pass, but the actual run of the show did not. In March 2020, according to Playbill, the show was shuttered, like the rest of Broadway, over legal measures seeking to limit the spread of COVD-19.