The Untold Truth Of J.D. Salinger

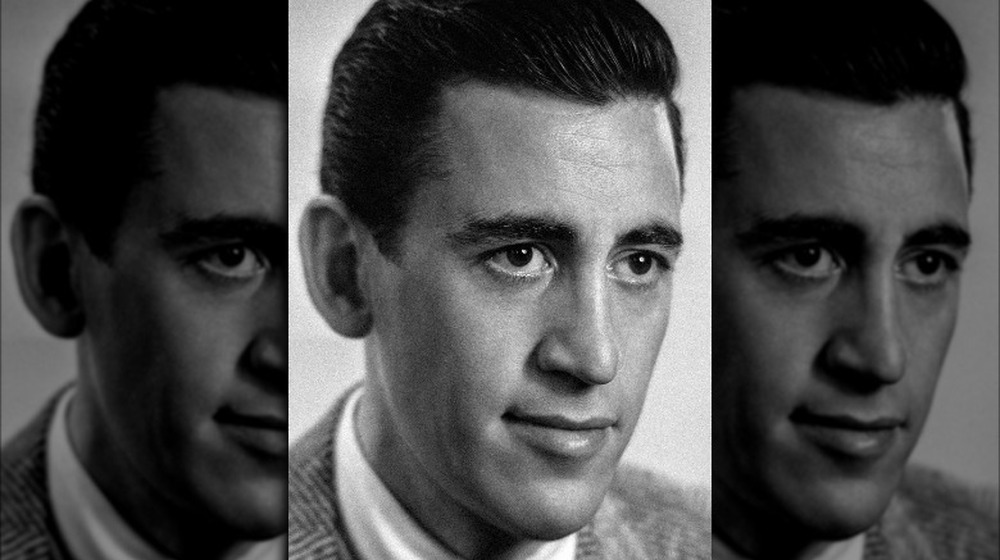

There is a central irony to the life of J.D. Salinger: that the more he decided to retreat from fame, the more famous he grew. His writing, including the novel The Catcher in the Rye, which was published in 1951 and continues to sell around 250,000 copies per year, according to The Irish Times, has come to be some of the most read, studied, and best loved in American literature. But, arguably, what really cemented his fame in popular culture in the second half of the 20th century was his decision to elude the public eye and live as a recluse, a decision he made in 1953, just two years after the release of the instantly acclaimed Catcher and the making of Salinger's name, per the Independent, which calls him the "world's most famous literary hermit."

In that phrase alone, the contradictions of Salinger's public life are writ large: in the end, his withdrawal from the world became just as famous as his writing — perhaps more so. But there is much more to the Salinger story than his slim bibliography and his decades of misanthropic self-seclusion, with many facets of his early years casting light on the reason he wrote — and lived — the way he did.

Salinger's brush with show business

One of the most famous images of Salinger was taken during his hermit years, by a magazine journalist who has caught the author unawares. The photo (top) shows Salinger glaring into the lens, enraged at the intrusion. But if Salinger truly had an aversion to fame, accounts of his early life contest that it wasn't a lifelong affliction — it was something he grew into.

Though he presented himself as a loner, Salinger was a keen "socialite" as a young man, according to the Independent, which also claimed that the writer had once dreamed of becoming an actor. The closest Salinger came was in 1941, when, in his early 20s, the future writer had a short spell as an entertainment director on a cruise ship, the MS Kungholm, per Cruise Line History. The Independent claims that Salinger's role was the organizing of entertainment, including dances and games, and that he would dance with single women and ensure everyone was enjoying themselves — not exactly the dream job for someone who is naturally antisocial. Salinger's carefree cruise lifestyle came to an abrupt end after just three weeks, when the liner was requisitioned for use in World War II. His experiences on the Kungholm would prove good material for his fiction, such as his 1947 short story "A Young Girl in 1941 with No Waist at All," a love story set on a cruise ship with the same name as that which employed young Salinger, according to Salinger.org.

Salinger wrote on the front lines of World War II

Salinger soon found himself drafted into the US Army as part of the war effort, serving from 1942-1944, according to Biography. Opening her biography of Salinger in Harold Bloom's "BioCritique" J.D. Salinger with a chapter titled "Horrors of War," the author and academic Norma Jean Lutz describes how the young Salinger — who was 25 when he started his military service; young, but considerably older than many of his fellow soldiers, a great number of whom were still in their teens — was at the center of horror during the D-Day landings, invading occupied France on Utah Beach, Normandy, which was heavily fortified by the Germans: "his introduction to the grim realities of war."

In his poem "air and light and time and space" (posted at Poem Hunter), Charles Bukowski claimed that, if you are ever going to create, you will even do it "while the whole city trembles in earthquake, bombardment, flood and fire." As Lutz's biography shows, this is exactly what Salinger did, building his budding writing career in the field, typing on a typewriter while traveling by jeep, communicating with editors and mentors by mail rather than friends and family.

But Salinger's experiences of war, which included the liberation of concentration camps, also deeply traumatized him. He returned home with post-traumatic stress disorder, according to the Independent, which claims he later told his daughter, Margaret: "You never really get the smell of burning flesh out of your nose entirely, no matter how long you live."

J.D. Salinger's disastrous first marriage

Though Salinger continued to write throughout the war, what he saw changed his outlook deeply. The pre-war exuberance that saw him dancing with single ladies as a cruise ship entertainment director had been replaced by a keen desire for stability and conventionality, the comforts of a normal peacetime life, though Salinger continued to work in a military capacity in Germany, helping to track down fleeing Nazis, according to The Times of Israel. He checked into a psychiatric treatment facility after what seems to have been a nervous breakdown.

Salinger was still undergoing treatment when he met and fell in love with Sylvia Welter, claims the Independent. Welter was a French-German woman he first met at the psychiatric clinic in Nuremberg. They married within weeks, but the fledgling romance in the early days of peace proved to be yet another blow to the mentally fragile Salinger, when he found out, per the same source, that his new wife had been an informer for the Gestapo.

In fact, per The Times of Israel, Welter was said to "hate Jews as much as [Salinger] hated Nazis," which — considering Salinger's Jewish heritage — makes their union all the more unfathomable. Their marriage was annulled within months, with the whole affair undoubtedly affecting Salinger enormously.

J. D. Salinger: pick-up artist

However, according to Norma Jean Lutz, some good fortune did befall Salinger during World War II: it gave him the chance to meet his literary hero, Ernest Hemingway.

Hemingway, who was already something of a legend during the 1940s, was living in the Paris Ritz as a war correspondent, and Salinger reportedly headed to the hotel with a friend and a copy of a recently published story. He found Hemingway supportive and approachable, and their meeting gave Salinger decisive encouragement to continue as a writer. Six years after World War II ended, Salinger's debut novel made him a literary megastar.

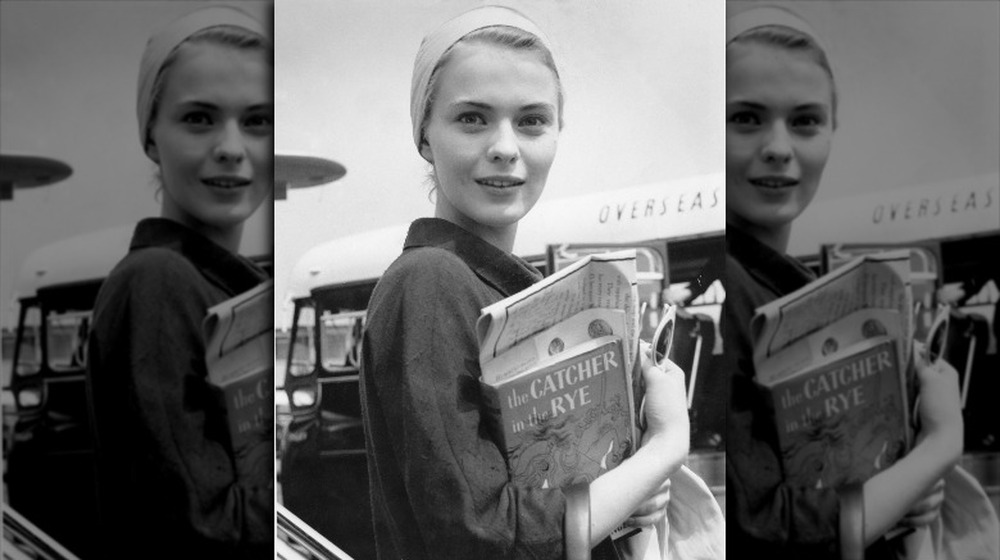

Though he withdrew from public life shortly after his rise to prominence, it is reported that Salinger was still willing to use his reputation for his own gain — particularly when it came to impressing young girls and women. According to the Independent, the Catcher author had a pick-up line that is so direct there is no doubt of the thinking that lies behind it: "I'm J.D. Salinger, and I wrote The Catcher in the Rye."

Salinger was married two more times following the annulment of his union with Sylvia Welter: first to Claire Douglas, a British teenager he met in 1954 (Salinger was in his 30s by then) with whom he would have two children before divorcing in 1967, and, in 1988, to Colleen O'Neill, to whom he would remain married until his death in 2010.

Salinger's obsessions and neuroses exposed?

As well as his marriages, Salinger had a great number of affairs throughout his life, with much younger women. One of these women, Joyce Maynard, dealt a blow to Salinger in the late 1990s when she exposed Salinger's obsessive behavior. According to The New York Times, she was a college freshman during their 10-month affair, and her book revealed details of Salinger's life: He ate frozen peas for breakfast; he had developed an unhealthy attachment to homeopathy. She also accused him of being "sexually manipulative." Two years later, Salinger's own daughter, Margaret, published another exposé that The Times says accused him of abuse and luridly listed his many bizarre obsessions, from acupuncture to urine-drinking.

Such accounts of the secretive author's private life irreparably damaged Salinger's reputation in his last decade and appeared widely in his many obituaries when he finally died in 2010, aged 91. But in 2013, one more lurid detail hit the headlines, when a new book, Salinger, by David Shields and Shane Salerno, made a surprising claim. In addition to the traumas he suffered in the war, much of Salinger's neurosis came from the shame he felt about the fact he had only one testicle, per the Atlantic. Shields and Salerno, who say that two women in Salinger's life had verified the deformity, claim in the book that "The war was one wound, but his body was the other. It was the combination of these wounds that made Salinger."