The Tragic Untold Story Of The 1871 Chinese Massacre

In 1871, the city of Los Angeles witnessed what would become one of the worst lynchings in the history of the United States when a majority white mob of Americans tortured and murdered over 15 Chinese boys and men. The next day, their bodies could be seen hanging in the makeshift gallows.

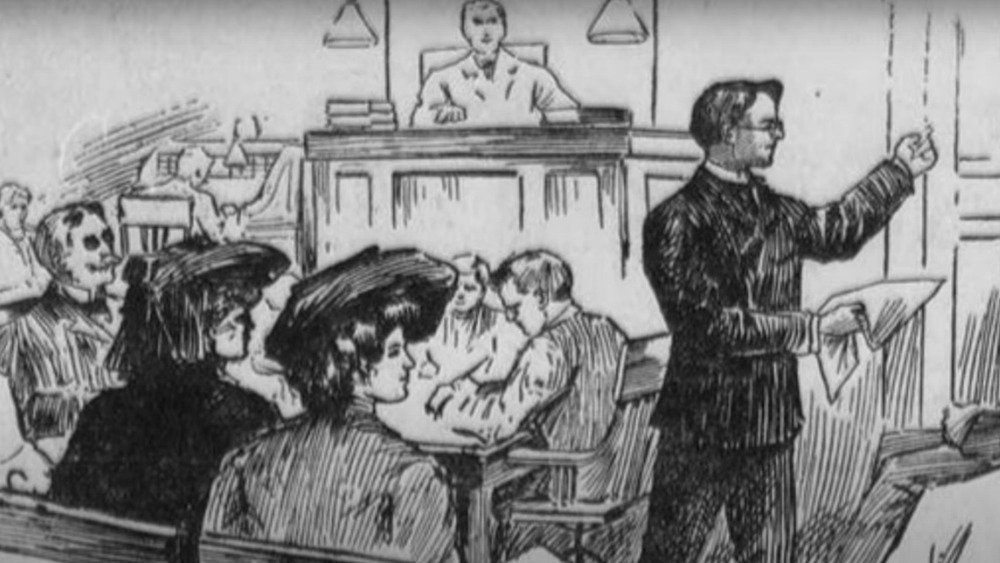

Despite the fact that a handful of people were put on trial for some of the murders committed during the massacre, all of the convictions ended up being overturned soon after the trials. And when several Chinese business owners sued the city of Los Angeles for the damage done to their stores during the mass lynching, the court ruled that people who have their "goods" destroyed during a riot aren't entitled to damages unless they had known that a riot was going to happen and had notified the mayor or sheriff about it.

Accounts of what preceded the massacre differ, but while many of the stories describe gang violence and jilted lovers, the real story appears to be much more complicated. And despite whatever happened before, nothing can justify what happened on the evening of October 24th. And as the massacre in Atlanta, Georgia on March 16th, 2021 demonstrated, the deep-seated roots of anti-Asian violence in the United States have yet to be fully addressed and reckoned with. This is the tragic untold story of the 1871 Chinese massacre.

Chinese immigration in the mid-1800s

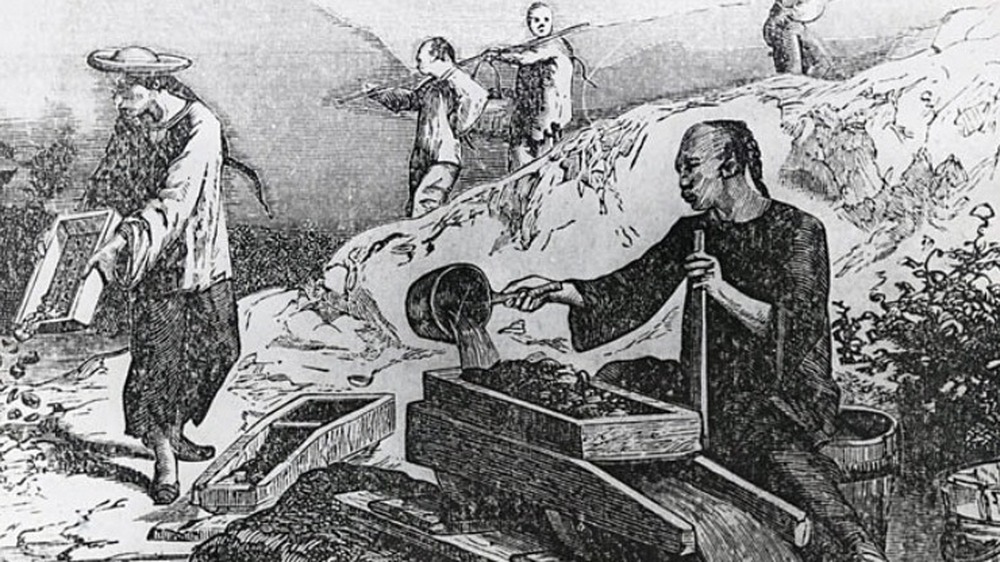

While Chinese people have been immigrating to the Hawaiian Islands since 1778, and there are reports of Chinese people in Pennsylvania before the 1800s, more and more began to immigrate to the mainland United States in the mid-1800s. In 1848, Congress considered a proposal to connect San Francisco to the Atlantic states via a transcontinental railroad, before gold was even discovered in California. And according to Strangers From A Different Shore, from its conception this plan involved the exploitation of Chinese laborers. In his proposal, Aaron H. Palmer wrote that "no people in all the East are so well adapted for clearing wild lands and raising every species of agricultural product... as the Chinese."

In response to the Taiping Rebellion as well as the California Gold Rush, Chinese migrants came to the United States as contract laborers and merchants. By the end of the 1860s, the Central Pacific Railroad employed almost 12,000 Chinese workers, "representing 90 percent of the entire workforce." Chinese laborers were also overrepresented in the mining regions, accounting for 70 percent of the population compared to 7.8 percent in cities like San Francisco.

Quartz writes that during this time, Chinese laborers were "blamed for stealing jobs and driving down wages" but in fact Chinese people in the United States throughout the 1800s made up less than 0.3 percent of the total US population. And since they "were not welcomed by trade unions," they had little power over their wages.

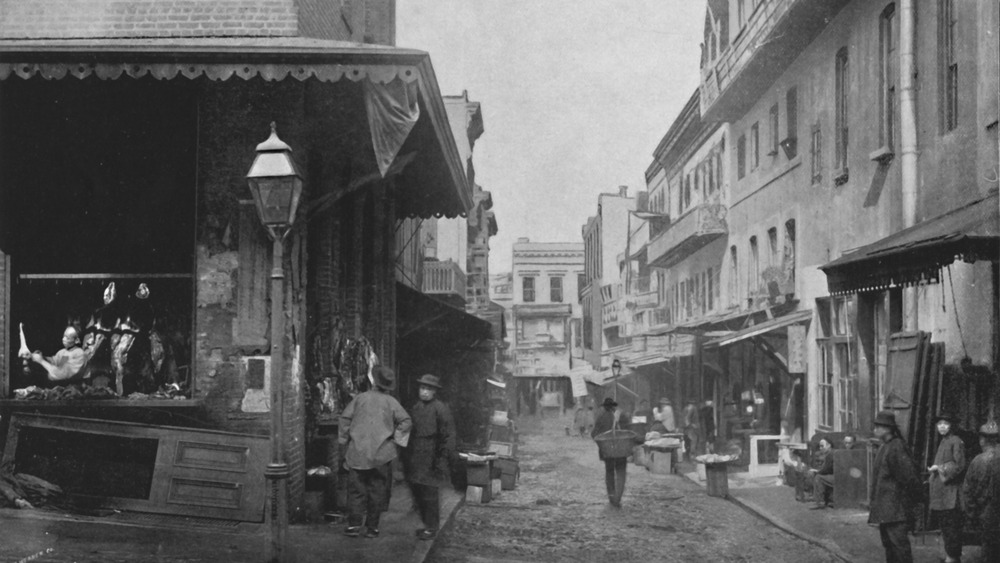

What it was like for Chinese immigrants living in Los Angeles

Chinese immigrants traveled across the United States, but many initially settled In California in cities like San Francisco and Los Angeles. Strangers from A Different Shore explains that laundry became the primary trade for Chinese migrants for two main reasons. First of all, it was comparatively much cheaper to open a laundromat than a restaurant or retail business. But more importantly, Chinese migrants were "pushed" into laundries since it was incredibly difficult to secure employment anywhere else due to discrimination from white employers and workers: "Thus the 'Chinese laundry' represented a retreat into self-employment from a narrowly restricted labor market."

And according to History News Network, many who operated laundromats went on to use the American legal system to defend their businesses: "They would go to the justice of the peace court to collect on a laundry bill of a dollar fifty. There would be a hearing and, in most cases, the Chinese [plaintiffs] would prevail." Ah Toy, one of the first Chinese sex workers in San Francisco, was also a frequent presence in the court room, and although she wasn't always successful in her cases, she was persistent. The World of Chinese writes that in 1852, Ah Toy even "challenged a Chinese gang leader in court who was attempting to extort her."

However, such legal battles came to an end when in People v. Hall (1854), the Supreme Court ruled that a Chinese person's testimony against a white person was inadmissible.

The Tong factions

In Cantonese Chinese, "tong" refers to a "gathering place," and when Chinese migrants came to the United States they established tongs as community organizations. According to Organized Crime, Corruption and Crime Prevention, tongs provided many services to newly arrived immigrants such as referrals for jobs, housing, networking, and recreational activities." Tongs also were respected mediators in the Chinese community, and "as a result tong leaders [were] often prominent community members."

Although the tongs were considered a criminal organization by the United States government, tongs weren't synonymous with criminality. As noted by You're Wrong About, what's described as a gang is almost always a group of ethnic minorities who are "outside of the legal and political structures of power" to such an extent that they form their own "parallel power structures." And since Chinese migrants were often denied employment opportunities in the mainstream workforce, some tongs got involved in the vice industry.

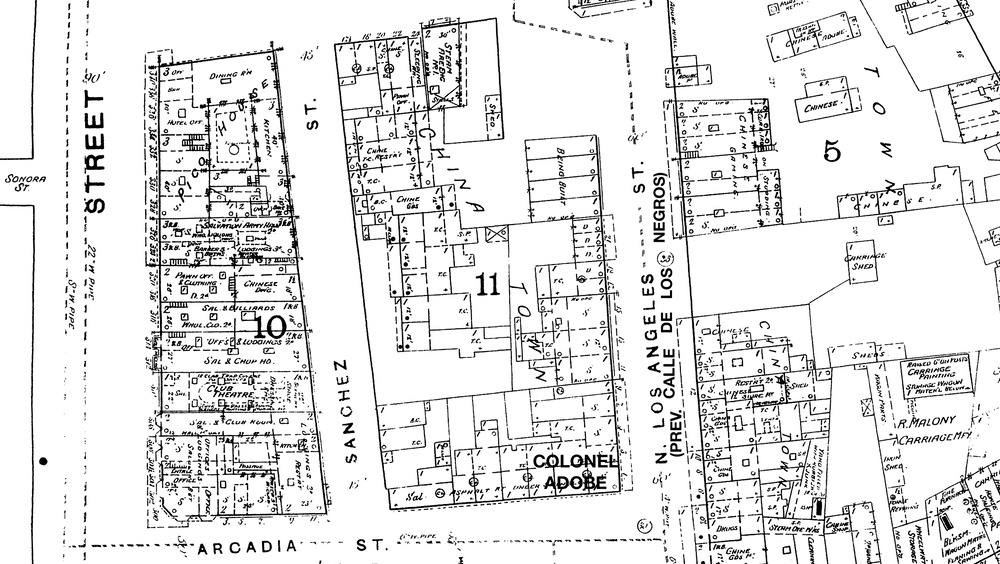

The 1871 massacre is thought by many to have been sparked by the violence between two rival tongs factions fighting over a married woman named Yut Ho who had been stolen from her husband. However, the real story isn't so simple and straightforward.

The sound of gunfire

On October 24th, 1871, Los Angeles police officer Jesus Bilderrain claimed that he heard gunfire from the direction of Calle de los Negros in Los Angeles, California. Upon arriving at the alley, he discovered a man named Ah Choy, Yut Ho's brother, bleeding to death from a gunshot wound to the neck, writes LA Weekly.

Noticing a group of Chinese men "fleeing" into the Coronel Building, Bilderrain initially stated that he ran after them into the building and almost instantly emerged from the building shot as well. However, it should be noted Bilderrain changed his story "several times in the months that followed." Whistling for help, a man named Robert Thompson, a civilian rather than a police officer, showed up to Bilderrain's aid. Thompson went in as Bilderrain had, and after taking a bullet to the chest, he died within an hour.

History News Network writes that before long, "rumors began to circulate within Los Angeles that the Chinese were 'killing the white men by wholesale.' That's an actual quote from witness testimony."

Who was Yut Ho?

Yut Ho was married to Hing Sing, a member of the See Yup Company. But according to The Chinatown War, on March 7th, 1871, "Lee Yong [of the Hong Chow Company] brazenly entered the older man's residence and brought out his wife, Yut Ho. He and his helpers put her in the carriage and took off." The carriage went to a Justice of the Peace, where they were married before "escap[ing] through a back door." The media described the event as a "romantic caper," while Hing Sing alleged that "Yut Ho had been illegally detained under a forced marriage."

While some have portrayed Yut Ho as a "woman for sale," the fact that her brother Ah Choy was also in the United States and her husband Hing Sing was a wealthy man, it's possible that she had come from China specifically to be a trophy wife.

Hing Sing and Lee Yong worked with rival tongs, or companies. However, even though it's unclear "whether Yo Hing and the Hong Chow Company intended to hold Yut Ho for ransom, force her into prostitution, sell her, or help Lee Yong keep her as a stolen bride," Yut Ho is always described as an unwilling participant despite the fact that no first-person account exists from her. As a result, it's impossible to know whether she actually wanted to be with her first husband, her second husband, or no husband altogether.

Was it all planned?

However, despite the story of a lovers' quarrel, there's evidence to suggest that Jesus Bilderrain was there that evening "not to investigate gunshots but to rob Sam Yuen," the head of the Nin Yung Company. According to LA Weekly, Bilderrain claimed that he saw the men who he believed wounded Ah Choy run into the Coronel Building. But the Coronel Building was Sam Yuen's building, and Ah Choy would've been wounded by Hong Chow's men if it were in regard to the alleged abduction.

There's speculation that the officer was actually working for Yo Hing and the Hong Chow Company, and was only there in order to take Sam Yuen's gold, whose wealth had been noticed just days earlier when he bailed some of his company members out of jail on October 23rd.

Plus, it's pretty certain that Bilderrain lied about at least part of the incident that sparked the riot, which seems very shady: "The officer insisted that he had seen Yuen shoot bar owner Robert Thompson, a remarkable feat given that Bilderrain was lying wounded in the street when Thompson was shot by someone in the dark interior of the building. Horace Bell, a lawyer and early chronicler of Los Angeles, wrote years later that he believed Bilderrain and Thompson went to Yuen's store that afternoon for no other purpose than to steal his gold."

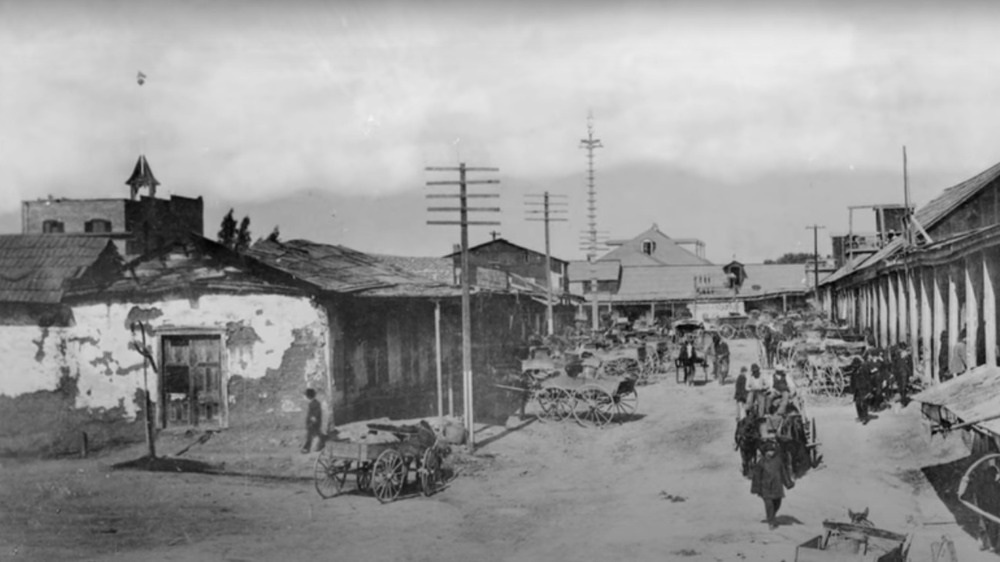

A mob retaliated against innocent Chinese immigrants

But despite the uncertainty of the events that took place before, the subsequent massacre is tragically clear. Learning of the death of a white civilian amidst rumors of further violence, a mob of 500 people— "nearly a tenth of the entire population of Los Angeles" —gathered in the alley and attacked Chinese boys and men.

History News Network writes that violence against the Chinese community wasn't new, but previously it had occurred on a smaller scale, with white people attacking individual Chinese people in the street. And because "you didn't see any non-Asians speaking out in protest [...] the perpetrators got the impression that they could get away with it. One of things that allowed the violence to spill out of control on the night of the massacre was the belief among the mob members that nothing would happen to them if they robbed and murdered the Chinese."

Groups of men erected gallows downtown, where they dragged young boys and grown men. "The porch roof of John Goller's wagon shop at Los Angeles and Commercial also had victims swinging from ropes. Goller objected bitterly as the Chinese were hoisted outside his windows, but was met with a rifle pointed at him," writes Vision Times.

Chinese immigrants were tortured and hanged

At least 15 Chinese boys and men were murdered that evening, though it's likely that the final death count was higher. Although the mob mostly consisted of white Americans, including some as young as 10, Latino Americans also participated in the mass lynching. Later accounts claim that "some of the city's leading citizens were seen cheering on the killers."

Some of the victims died by hanging, while others were tortured and shot before they were strung up. The day after the massacre, the residents of Los Angeles could see bodies hanging by the town's jail building in double rows.

Dr. Gene Tong (Chee Long Tong), a local apothecary, was one of the many victims of the massacre. According to LA Weekly, when Gene Tong was being dragged, he tried to negotiate with the men abducting him. He said that he had gold in his shop, and he offered his wedding ring, but "instead of negotiating, one of his captors shot him in the mouth to silence him. Then they hanged him, first cutting off his finger to steal the ring."

Indictments passed

During the coroner's inquest to identify the killers, none of the witnesses, "including police," were initially able to point out who was responsible for the murders during the massacre. After four days, according to The Homestead Blog, the coroner's jury concluded that there was enough evidence to indict over 100 people as "having taken part in the destruction of the lives and property of the Chinamen." The grand jury lasted for three weeks and when it finished, it issued 49 indictments, "roughly half for murder and the rest constituting a variety of felonies, and there were over 150 persons named."

Several men were indicted for the murder of Dr. Gene Tong, but notably "not one prominent person was on the [entire] list."

The following year, several civil and criminal trials began, but not all those accused by the grand jury were brought to trial. Ten men had been indicted on criminal charges, but their trials were separated, with one of them, L.F. Crenshaw, standing alone while the other nine had their case combined into one.

Convicted and appealed

Out of the 10 men indicted the murder of Gene Tong, eight of the men ended up being convicted of manslaughter, with sentences ranging from two to six years. However, their lawyers, Volney Howard and E.J.C. Kewen, had seemingly planned on this. "Kewen pulled out his ace not long after the guilty boarded ship for San Quentin," filing papers with the Supreme Court of California claiming that the convictions must be overturned because the district attorney had made a technical legal error.

According to The Homestead Blog, "it was determined [that] the indictment issued by D.A. Thom in each instance is fatally defective in that it fails to allege that Chee Long Tong [Gene Tong] was murdered." The opinion added that even if the defendants did what was alleged "still it does not follow, by necessary legal conclusion that after all any person was actually murdered."

Essentially, even though everyone agreed that Dr. Gene Tong existed and had been murdered, the district attorney didn't explicitly say this in his indictment, nor had he introduced evidence during the trial to demonstrate that Tong had been murdered. As a result, in 1873 all of the manslaughter convictions were overturned.

Banning Asian women first

Four years after the massacre, the United States issued its first ban on Chinese immigration. The Page Act of 1875 restricted contract workers and women who were being brought over for "immoral purposes" from China, Japan, "or any Oriental country." Despite the fact that not all Asian women who immigrated to the United States were sex workers, suddenly they were all being treated as such.

According to Duke Law School, the United States government instituted this ban in an attempt to minimize the number of Chinese-American children, while simultaneously maintaining "America's international trade objectives and treaty obligations [which] made outright restrictions on Chinese immigration untenable in 1875."

And it's certainly not as though the immigration of sex workers of other ethnicities was being restricted at this time. And during this time, prostitution was a legal occupation in some U.S. states, like California. Despite protestations that the law was in the interest of women who had been sex trafficked, there's no evidence to suggest that any sex trafficking victim was consulted during its creation.

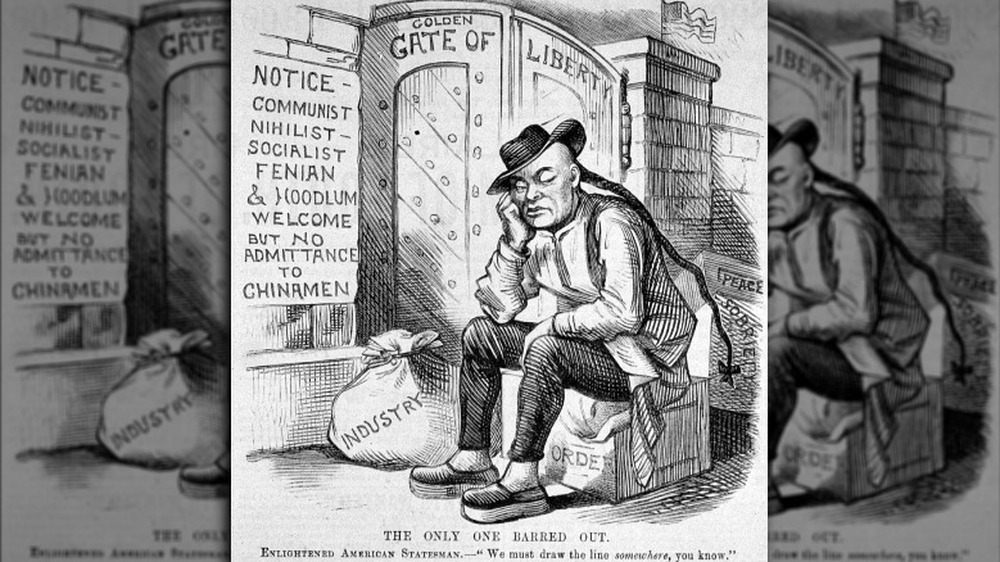

The Chinese Exclusion Act

Seven years after the passage of the Page Act and 11 years after the massacre in Los Angeles, the United States passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, barring Chinese immigration to the United States. In the years around the passage of the Exclusion Act, the population of Chinese people in the United States stood still around 105,000. During this time, the population of the United States was around 50 million.

The Office of the Historian writes that "Some advocates of anti-Chinese legislation therefore argued that admitting Chinese into the United States lowered the cultural and moral standards of American society. Others used a more overtly racist argument for limiting immigration from East Asia, and expressed concern about the integrity of American racial composition." According to "Institutional Discrimination and Assimilation," the Exclusion Act not only affected the immigration of Chinese people into the United States, but affected people of Chinese descent in the U.S., who suddenly found "institutional discrimination diffused [into] every aspect of their daily activities."

As the United States repeatedly extended the Exclusion Act, they started requiring people of Chinese descent to carry identification, denying those with prior residence, and conducting immigration raids with arbitrary arrests and detentions. The exclusion ban wouldn't be lifted until 1943.