The Story Of The First Woman In America To Earn A Medical Degree

Women were working as healers long, long before American men built medical schools and informed women they weren't allowed to go there. Peseshet would have laughed if someone had told her women couldn't be capable physicians — she was practicing medicine in Egypt like 4,500 years ago. She may not have been the first, either, and she was certainly not the last. Women healers have always been a thing. Sure, they were often persecuted, threatened with death, and occasionally actually killed, but that didn't stop more women from following in their footsteps.

Even though the history of women in medicine goes back thousands of years, it wasn't until relatively recently that women got to train to be physicians on the same level as their male counterparts. The first American medical school opened in 1765 and like pro football and backyard clubhouses it was for Boys Only.

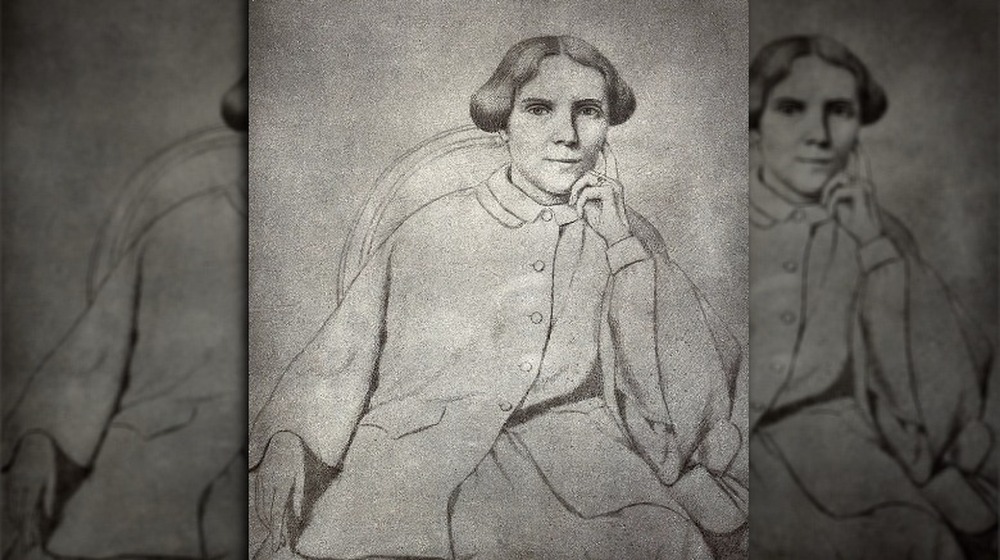

Until Elizabeth Blackwell came along. Here's the story of America's first female physician, or at least, the first one to do it the new-fashioned way: by graduating from medical school.

Elizabeth Blackwell came from a progressive family

Even today, women entering traditionally male professions face hurdles. Ironically, you kind of have to have a pair of cojones to walk into that world and come out of it a better person. Now imagine doing such a thing more than a century ago, when there was pretty much no one supporting you, including other women. You couldn't do it unless you had really thick skin and a really determined heart.

That was Elizabeth Blackwell — born in 1821, she was the third of eight children in an unusually progressive family. According to Hobart and William Smith Colleges, her parents believed that girls and boys should receive the same education, and the whole family was active in the abolitionist movement. Patriarch Samuel Blackwell was a co-founder of the Bristol Abolition Society and for a time the family even housed a runaway slave. Unfortunately, the Blackwells also had to endure a lot of hardship. Samuel owned a sugar refining business that went under in the 1830s, prompting the family to abandon their life in England and sail to America.

The hardship didn't end when the family settled in their new country, because Samuel died just a few years later. The tragedy might have sent other families into a tailspin, but Blackwell and her sisters avoided ruin by founding a boarding school for girls. So even before her 18th birthday it was clear that Blackwell wasn't afraid of adversity.

Elizabeth Blackwell was inspired by the tragic death of a friend

There's no doubt that Elizabeth Blackwell had the personality and intelligence a woman of her time needed to break into the male-exclusive medical profession, but she didn't always want to be a doctor. Because really, why would you want to do such a thing when there were so many seemingly insurmountable barriers deliberately put in your way? It wasn't just that, though; according to Changing the Face of Medicine, Blackwell herself wrote that when she was young the idea of practicing medicine actually repelled her. "The very thought of dwelling on the physical structure of the body and its various ailments filled me with disgust," she said.

But that changed — or at least became less of a deterrent — when a close friend named Mary Donaldson developed a terminal illness. The nature of her illness isn't clear, but it was something gynecological, possibly uterine cancer. Donaldson told Blackwell that the embarrassment of repeat examinations by male doctors had added to her suffering. After Donaldson's death, Blackwell was haunted by the thought that her friend might have died because she'd been afraid to seek treatment until it was too late. That was enough to inspire Blackwell to change her life plans and overcome her personal feelings about anatomy and medicine. Becoming a doctor, she wrote, "gradually assumed the aspect of a great moral struggle."

Here's what Elizabeth Blackwell was up against

You can probably imagine the professors looking down their noses at the intruding female student, and the young male students who didn't have to weigh their behavior against fantastical ideas like equal treatment and women's rights because those things were a long way away from being mainstream. But those weren't the only barriers in Blackwell's way. Before she even got into medical school, she had to overcome ideas that were an uncontroversial part of American culture. According to Social Welfare History Project it wasn't just a "we don't want to let you in our club" kind of thing: it was a deep-seated belief that a woman who studied medicine would become morally bankrupt, you know, because her delicate woman's constitution wouldn't be able to handle knowing words like "uterus" and "ovaries" or something. So it wasn't just that medicine was "man's work," it was that practicing medicine would turn a woman into an abomination.

Okay, so that is a big hurdle. But Blackwell wasn't the first woman to try getting into medical school — before her came Harriot Hunt (pictured), who applied to Harvard Medical College in 1850 and was turned away because "no woman of true delicacy" should want to be a doctor, never mind if the woman in question gave a damn about stupid things like "delicacy." (Incidentally, Hunt later went on to become a successful but unlicensed physician).

Not every male doctor thought women should stay out of medicine

Before there were medical schools, doctors typically became doctors by completing an apprenticeship. That's also the route that determined women would take, knowing that they'd never be able to attend medical school. That might have been Elizabeth Blackwell's fate, too, except for a bit of strange luck.

Before that, though, Blackwell corresponded with physicians practicing in her local area, hoping to find some advice and encouragement on how she might be able to obtain a medical education. According to the Embryo Project, most of the doctors she wrote to were sympathetic, but ultimately not super optimistic. She did find a few early allies, though, including a former physician named John Dickson, who invited her to board with his family while working as a teacher in North Carolina. In her spare time, Blackwell studied his medical books. When she was 25, she made a similar arrangement with another doctor in South Carolina. So she wasn't doing apprenticeships, exactly, but she hoped she'd gain enough knowledge from those extracurricular activities to give herself a leg up into medical school.

First the rejections, then the practical joke

These days, that kind of dedication would be a big plus in a college entrance essay, but it did exactly nothing for Elizabeth Blackwell. According to the Embryo Project, Blackwell applied to 30 different medical schools and received rejection letters from 29 of them. You might be thinking, "Hey, at least there was one school out there that recognized her potential and decided to be progressive!" But that's not how it went down at all. Blackwell's acceptance letter from Geneva Medical College was meant to be a joke.

There are a couple of different versions about what exactly happened and why, but the story told by Smithsonian is that the dean of Geneva Medical College made the odd choice to let his students decide if they wanted to admit a woman to their ranks. He was reluctant to outright reject Blackwell's application because it came with a recommendation from the respected doctor she was studying with, so he put the question in front of students with the caveat that if just one of them said no, Blackwell's application would be rejected.

Naturally, he expected the vote to happen differently than it did. The students thought the whole thing was a joke and gleefully voted yes — every single one of them. Lucky for Blackwell, the dean was a man of his word. Blackwell received her acceptance letter in 1847 and joined the Geneva Medical College student body in August of that year.

Med school did not turn out to be especially fun

After that it was a clear path ahead. Everyone recognized Elizabeth Blackwell's potential, and she lived happily ever after. Haha, no, obviously that's not what happened at all. According to NPR, she did earn some respect inside Geneva Medical College. She was a hard worker, clearly very intelligent, and the professors eventually caught onto the fact that her presence there would make their school a household name. On the other hand, there were a lot of people outside of the college who treated her like the abomination that they clearly thought she was. It wasn't just a general feeling of being disliked, either. People stared at her and gossiped. At best, they thought she was a crazy person, and at worst, they thought she was immoral and ushered their children away when they saw her. Doctors' wives seemed to take a particular dislike to her and wouldn't speak to her. Blackwell could really feel this animosity when she went out into the town, so she pretty much avoided going anywhere but back and forth to her classes.

Even so, Blackwell not only persisted, she also finished first in her class. The professor who gave the valedictorian speech during Blackwell's graduation ceremony praised her hard work and dedication, but then went on to imply that he hoped no other woman would ever follow in her footsteps.

Then all the other doctors got angry

Right up until Elizabeth Blackwell's graduation, most people seemed to treat her existence as an inconsequential anomaly, probably believing that she'd fail spectacularly, thus proving they'd been right all along about the unfitness of women to practice medicine. Then when she didn't fail, that sparked a nationwide debate about whether or not women could be competent doctors.

According to Hobart and William Smith Colleges, shortly after Blackwell obtained her medical degree, The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal (the former name of today's New England Journal of Medicine) published a letter from an anonymous person that basically summed up what everyone else was thinking — that women were unfit to work as doctors and what had happened at Geneva Medical College went against the natural order of things. In response, the professor who had delivered the valedictorian remarks at Blackwell's graduation wrote a strange rebuttal, in which he defended the possibility that competent women medical students were possible but said that they shouldn't be allowed into any more medical schools because they created too much inconvenience for the male students.

Elizabeth Blackwell eventually went back to Europe to continue her education

Elizabeth Blackwell had triumphed over the sexism of the American medical institution — sort of — but even she recognized that it might not be worth the effort to keep pursuing her education in that very unwelcoming environment. According to the Embryo Project, after graduation she decided to go back to England, and then eventually to France where she'd been told they were less hostile towards female physicians.

Blackwell got a job working at a maternity hospital while pursuing her dream of becoming a surgeon. Unfortunately, her plans changed when she was treating an infant with purulent conjunctivitis. While flushing the child's eye out, some of the saline solution splashed into her own eye. Blackwell's colleagues treated her eye aggressively with hourly saline flushes and some other sketchier remedies like face leeches and purgatives, but it didn't save her eyesight. She became blind in that eye, which basically disqualified her from ever becoming a surgeon.

Blackwell didn't let a little thing like partial blindness deter her, though. She returned to the United Kingdom and got an internship at St. Bartholomew's Hospital in London, where she took up the cause of hand washing. That's right, hand washing, because doctors still weren't aware that it was a good idea to wash their hands between handling a corpse and delivering a baby. Blackwell was way, way ahead of her time.

Elizabeth Blackwell tried to partner with Florence Nightingale

Unless you count Nurse Ratched, Florence Nightingale is probably the most famous historical nurse. She was the founder of modern nursing, working tirelessly to improve healthcare during a time where healthcare was still pretty brutal and primitive.

Elizabeth Blackwell and Florence Nightingale met in 1850, just after Blackwell became well known for bucking the system with her unconventional medical degree, and just before Nightingale became famous for her tireless work during the Crimean War. According to The Lancet, when they reconnected in 1859, it was because Blackwell hoped to find a female ally in the still very male-dominated world of medicine. Her goal was to establish a women's hospital away from the city, which would employ only women and eventually also support a medical college. Nightingale poo-pooed the idea, believing that a small women's hospital "on a farm in the country" would be too insignificant to bother with. Nightingale later called Blackwell's idea "mischievous jargon" and basically said that women physicians benefited no one except themselves.

Despite their differences, the two women continued to correspond over the years, though they never did see eye-to-eye on the place of women in the medical profession. Both women died in the same year, but Blackwell kind of had the last laugh because the doctors who treated Nightingale in her last days were both women.

Elizabeth Blackwell shunned marriage, but not motherhood

Elizabeth Blackwell did a lot of things that weren't typical for women of her time, and one of them was vowing to never get married, partly because of past heartbreak. In her diary, Blackwell wrote that a career would "place a strong barrier between me and all ordinary marriage ... which will fill this vacuum and prevent this sad wearing away of the heart." She wasn't the only woman in her family who did the same. According to the New York Times, all four of her sisters also shunned marriage because it represented a barrier to independence and a lasting career.

Still, it's kind of natural for human beings to want to live with other human beings. Almost no one stays happy just living alone with their books. In 1854, the 33-year-old Blackwell was suffering from depression and loneliness and decided to become a mother. Of course, an unwed pregnancy would have been too scandalous even for Blackwell, so instead she adopted a 7-year-old Irish orphan named Katherine Barry. It was a bit of a strange relationship — the girl was described by some sources as "half ward, half servant" — but still, Barry was devoted to her adopted mother and lived with her until Blackwell's death in 1910. In return, Blackwell paid for Barry's education and provided her with a comfortable life, which is not something most orphans of the time got to have.

Back in the USA, no one would hire her

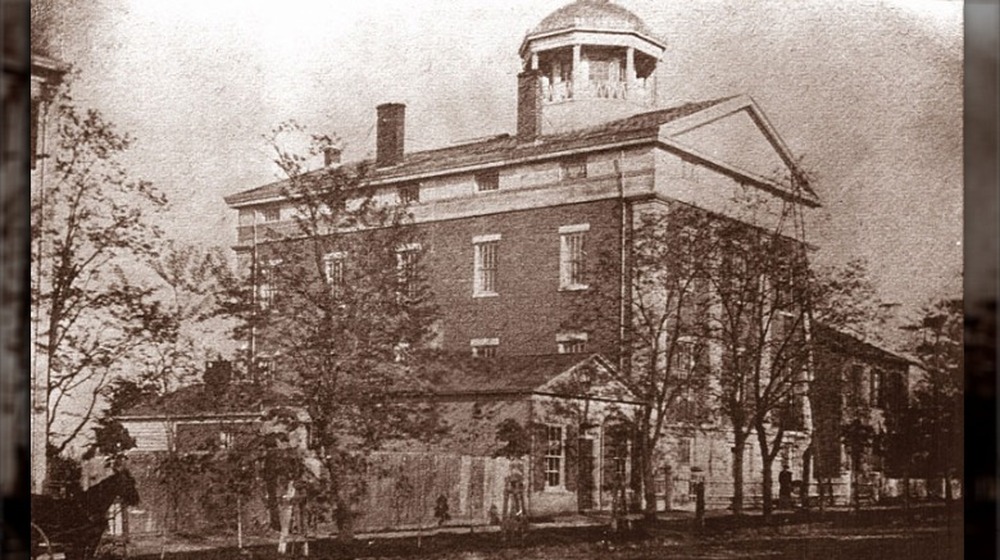

Elizabeth Blackwell returned to the United States in 1851, for reasons that are not super clear. America was still really hostile towards the idea of a female doctor, and no hospital in the United States would hire her. By now you're not surprised to hear that Blackwell was totally undeterred by this new reality, so instead of wasting her time applying for more jobs with people who were already 100 percent disinclined to give her a chance, she set up her own practice in 1853.

According to Notable Biographies, Blackwell's practice was pretty modest. It was located in a rented room and her patients were poor women, but word soon got out and by 1857 the practice had grown into the New York Infirmary for Women and Children. The infirmary not only treated women patients, it also employed women doctors, making it a first-of-its-kind institution for the United States. The infirmary evolved into a medical school, and eventually merged with the Cornell University medical school. The merger brought a large number of women into the student body at Cornell and was a big step forward in making women in medicine mainstream.

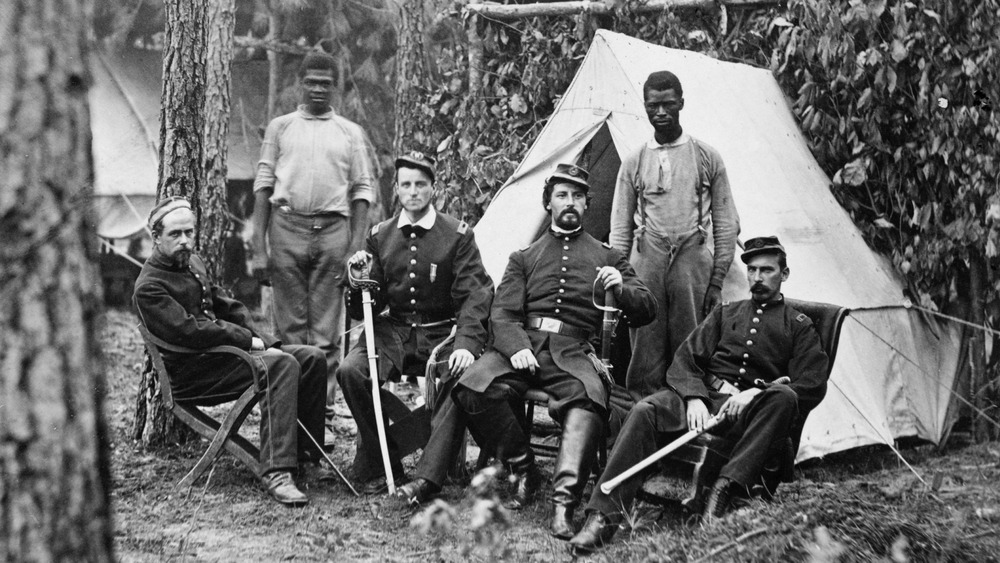

Elizabeth Blackwell worked tirelessly to help soldiers during the Civil War

Elizabeth Blackwell returned to the United Kingdom in 1858, but she only stayed for a year. Back in America, civil war was brewing, and Blackwell felt called to help ease the suffering of Union soldiers. The Rochester Regional Library Council says that shortly after hostilities broke out in 1861 she helped establish the Women's Central Association of Relief (WCAR), a volunteer organization that assisted women who wanted to help the war effort figure out what to send and where to send it. WCAR distributed things like food, blankets, clothing, and medical supplies to troops on the front lines. WCAR was so instrumental in the war effort that it became clear a national version of it was needed, and that early organization eventually evolved into the American Red Cross.

Meanwhile, Blackwell was also working with a small group of physicians to train women to become army nurses. Until that point, there was no formal training program for nurses in the United States. So Blackwell was making history all over the place, and still history barely remembers the part she had to play.

She didn't get nearly enough credit

During her long life, Elizabeth Blackwell achieved a lot of firsts. She was the first woman in the United States to obtain a medical degree, and she graduated first in her class. She established the first American hospital for women that was also staffed entirely by women. The medical school she founded was the first to prioritize women students, and she helped establish the first American training program for nurses. And according to the Rochester Regional Library Council, she was also the first woman to earn a spot on the Medical Register of the United Kingdom. Still, there's a good chance that many of the people reading about her here were previously unaware of her existence, while nearly everyone has heard of Florence Nightingale.

Blackwell continued to practice medicine almost until the end of her life. She died in 1910 and was buried in Scotland.