Tragic Details About Orson Welles

Few people in film history are more fascinating, infuriating, and complex than Orson Welles. For many, he's best known for Citizen Kane, the 1941 movie that marked a young Welles as a brilliant filmmaking auteur. Yet, Welles would go on to live for much longer than that, working until 1985 and producing a legacy that marked not only the movies, but radio, theater, and pop culture. He would likely be pretty frustrated to learn that, more than three decades after his death, people are still reducing him to his work on his very first feature film.

In truth, much of Welles' brilliant and tumultuous life was marked by tragic and semi-tragic details such as the above. He was marked as a child genius, yet came from a broken home. He gained great acclaim for his films, yet grappled mightily with studios when it came to creative control. He was a profound artist who was also a micromanaging director and an agonizing coworker. He was a romantic who also had three wives in succession and was often an absent father who often ignored his daughters in favor of his art. In short, Welles' life story contains just as much tragedy and missed opportunities as it does drama and brilliance.

Orson Welles had a difficult childhood

Before he was even 10 years old, Orson Welles had experienced some serious upsets in his young life. According to Britannica, he was born to Richard Welles and Beatrice Ives in Kenosha, Wisconsin in 1915. His parents separated when he was four and Beatrice died when he was nine. Not long after, he was admitted to the Todd School, a preparatory academy that offered him intellectual advancement and an educational philosophy that, according to Orson Welles and Roger Hall, was a "severely progressive" environment that encouraged creativity amongst its students. However, this move also meant that Welles moved to Illinois, separating him from his family at what was surely a vulnerable time in his life. Richard would die in 1930, orphaning a teenage Orson, who then became the ward of a family friend.

Young Welles was also an artistic prodigy. He played piano and violin, wrote poetry, made visual art, and seemed pretty inclined towards the dramatic arts. Yet, he was also a sickly child, as The New York Times reports. Welles was born with a spinal issue that caused numerous health problems. He also had, according to at least one childhood doctor, the spooky ability to weigh in on the philosophy of medicine from the comfort of his crib.

The War of the Worlds radio incident made him notorious

Though Orson Welles was striking enough to make an impression on people like his childhood doctors and high school teachers, he didn't really come to wider attention until 1938. That's when Welles, along with CBS Radio's The Mercury Theatre on the Air, broadcast an adaptation of H.G. Wells' novel, The War of the Worlds, as the CBC reports. Yet, where Well's novel was plainly fictional, Orson's broadcast was a different beast altogether. Presented as if it were breaking news, the program presented itself as an on-the-ground account of a real extraterrestrial invasion of Earth. It certainly seemed that way to some listeners, who promptly freaked out and assumed that the world was ending.

Later examinations of the incident indicate that reports of mass hysteria were probably overblown, but it is nevertheless clear that Orson Welles became a notorious figure in the aftermath. Smithsonian Magazine reports that he was only 23 at the time and would spend much of his life either apologizing for the turmoil he'd caused or cheekily hinting that he knew it would be a mess all along. Whatever his real motives, it was undeniably true that Welles was doing his best to mimic a real live radio broadcast, dramatically changing the original novel in the process. "We weren't as innocent as we meant to be when we did the Martian broadcast," he later admitted to the BBC (via Columbia Journalism Review).

Citizen Kane haunted Orson Welles

Today, Orson Welles is probably best known for his 1941 film, Citizen Kane. The movie, which follows the life of a newspaper magnate character closely modeled on the real-life mogul William Randolph Hearst, has since been widely hailed as one of the best movies of all time. It also proved to be a millstone around Welles' neck for the rest of his life.

The problem was that a young Welles was given broad creative control over Citizen Kane, an unprecedented move for the time, The Wire reports. Even more extraordinary was the fact that, at only 25, Welles was a first-time director. Much as he might have been riding the high of this honor, the release of Citizen Kane was disappointing, getting good reviews but not many ticket sales. It didn't help that Hearst himself realized that he was the inspiration for the titular Kane and, being rather sore about it, banned mention of the movie in all of his newspapers.

Welles believed that the film's initial flop set the stage for his later struggles with studios over who was supposed to make his movies. Citizen Kane effectively spoiled the self-involved Welles for all other collaborative filmmaking experiences. As a result, he later called Citizen Kane "the greatest curse of my life."

Orson Welles ran afoul of the Hollywood blacklist

Like quite a few other creative folks in the mid-century American film industry, Welles was a generally pretty progressive sort of person. And, like so many of those people, they soon ran into trouble in some circles for having the "wrong" sorts of views in an increasingly tense and image-conscious world. Orson Welles was about to butt heads with the Hollywood blacklist.

As History reports, Welles was put under investigation by the FBI in part because Citizen Kane was interpreted as a thinly veiled critique of William Randolph Hearst, an anti-Communist newspaper mogul. Under this line of reasoning, anyone who didn't like Hearst was therefore a potential Communist themselves. Never mind that, as the New Yorker points out, Welles was not a member of the Communist Party and hadn't done much political organizing beyond some leftist scripts and plays.

Welles was put on a watchlist and later included in the "Red Channels" pamphlet, a list of 151 artists and journalists whom right-wing commentators believed were helping the Commie cause in the United States (via NPR). Yet, by the time the pamphlet came out in 1950, Welles was already in Europe, having left a film industry he had already deemed overly restrictive. He was, in many ways, already in exile and beyond the reach of the Red Scare.

Orson Welles constantly fought with studios over creative control

After Citizen Kane, much of Orson Welles' filmmaking career was marred by constant struggles with film studios over who, exactly, was to make the films that would bear his credit. Though Welles would eventually admit that he did, in fact, need to collaborate to some extent with other people in order to make a movie, he wanted to always be the "dominant personality", as Despite the System reports. Unfortunately, this often meant that Welles intentionally destabilized productions with endless rewrites and reshoots, prolonging the struggle and not exactly endearing himself to his fellows.

As a result of these struggles, Welles often undertook independent projects that gave him control, as The Telegraph reports. But they were frequently held back by poor funding and planning. Welles was forced to play along in other productions, including a starring role in the 1949 film noir, The Third Man. Yet, he must have always been thinking of his "real" and oftentimes frustrating work, like the on-again, off-again, constantly cash-strapped production for his beleaguered adaptation of Shakespeare's Othello. At least that film got released in 1952, per The Criterion Collection, unlike some of his other, more struggling projects that would remain unfinished at the time of his death.

Welles struggled with his weight and how people perceived his size

Like so many Hollywood stars, Orson Welles was forced to fret over his image. According to the biography Orson Welles, the issues started at least as early as his involvement with Citizen Kane. Welles went on crash diets to slim down for the role. One diet had him eating only bananas and milk.

Other "diets" were a steady supply of pills loaded with amphetamines, as Orson Welles: Hello Americans reports. Early on, Welles was enthusiastic about the effects of the diet pills, though he later recognized that these were a hasty choice in an era before everyone admitted that packing your body full of amphetamines was pretty bad for one's health.

Later on in his career, Orson Welles appears to have discarded the diets and allowed his weight to balloon. According to Vice, he was notorious for his love of fattening steaks and ate them regularly, to the point where his considerable girth became part of Welles' image. It was part of a long-lasting caricature of him, perhaps as persistent and potentially damaging to Welles the man as his association with Citizen Kane. He was, for many, the cartoonish image of a louche, overweight film auteur and less so a complicated human being dealing with weight issues, like so many others both then and today.

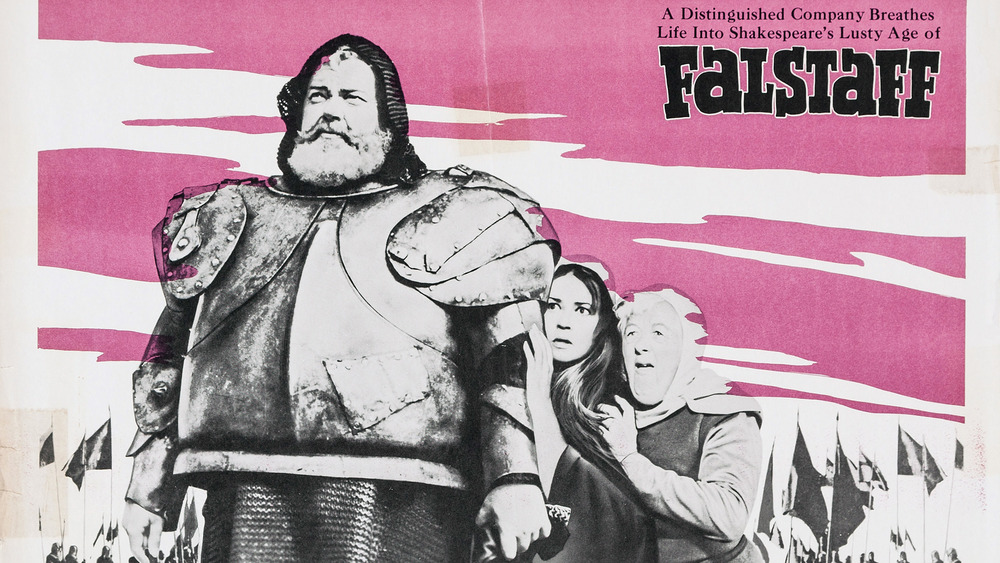

People don't really talk about his best film

Even though Orson Welles died in 1985, it appears that his first film, Citizen Kane, is still haunting his legacy today. That's because everyone feels obligated to talk about it when discussing Welles. It's the pinnacle of filmmaking, many say, an absolute highlight of Welles' career. Yet, it's possible that, for each time someone talks on and one about Kane, they're missing another opportunity to discuss the film that Welles himself considered his very best.

That work would be Chimes at Midnight, a quasi-adaptation of Shakespeare's Henry V that focuses on the fat, riotous and entirely made-up character of Falstaff, young Prince Hal's best friend and mentor. According to the New Yorker, for a long while, it was notoriously difficult to find a decent copy of the film, which is a real shame. Chimes at Midnight shows the combination of grandiosity and self-awareness in Falstaff that was also arguably part of Welles' own sense of himself, of a man who is eventually overcome by the caricature of himself.

It's also just a good movie. As the Folger Shakespeare Library notes, it's full of Welles' trademark inventiveness and passion, from smart camera moves to excellent acting. Welles himself, of course, stars as Falstaff. He was, by all accounts, awfully proud of this particular work. "If I wanted to get into heaven on the basis of one movie," he said, "that's the one I would offer up" (via Columbia Journal).

Orson Welles had a tumultuous personal life

At a certain point in his life, it was clear that Orson Welles wasn't going to be conventional. Early on, as a child prodigy and wunderkind producer, it was clear that he was ready to push intellectual and artistic boundaries. And, as he aged, Welles made it pretty clear that he wasn't especially committed to social conventions, either. As the New Yorker reports, Welles was married three times and had three children. The first marriage, to actress Virginia Nicolson, happened when he was only 19.

But, according to Express, Welles was never terribly faithful. So what if the pair had eloped in what must have been a spontaneous act of romance or at least impulsiveness? Welles was already carrying on affairs with other women soon into the marriage, a pattern he repeated continuously throughout his life. That reportedly ruined his second marriage to Rita Hayworth, who dropped him for cheating on her by 1948. He then married Italian actress Paola Mori in 1955. Though he paired up with actress and artist Oja Kodar for the last 24 years of his life, he often took his leave of her and returned to Paola.

Welles' three daughters were painfully cognizant of their father's artistic achievements and of his failures as a parent. Chris Welles Feder, his oldest daughter, wrote in In My Father's Shadow that he was both "a great creative force" and a dad who often wasn't there.

Sometimes Orson Welles was just difficult to like

Even as a young man, it was clear to many that Welles was a passionate, hardworking, and awe-inspiring talent. He was also a real pain in the neck. In The Guardian, biographer Simon Callow has admitted that Welles had a "stubborn lack of self knowledge" that made him both brilliant and difficult to work with, even for the most dedicated collaborators.

Welles also had some prickly comments about his fellow creatives, as Open Culture reports. Anyone who he deemed to be artistically lacking could be subject to his bracing judgments. Thus, Alfred Hitchcock had succumbed to "egotism and laziness", as Welles put it. Woody Allen, to his mind, "sets my teeth on edge [...] Like all people with timid personalities, his arrogance is unlimited."

Moreover, Welles could be a real pain on set if he thought the film was beneath him. Callow, in Orson Welles, writes that he "behaved more or less badly on virtually every film he did not direct." Any movie not directed by Orson Welles was, to Welles' own mind, an inferior product. This meant that he gave unasked-for and sometimes impossible to implement suggestions, all while rolling onto a film set late in the day and then sometimes even directing his own scenes while the actual director helplessly stood by.

Orson Welles filmed some embarrassing commercials

Later in life, Orson Welles lent his distinctive voice to a series of commercials that ultimately tarnished his reputation and contributed to the cartoonish pop culture pictures of Welles as a self-involved, ridiculous blowhard. The Paul Masson wine advertisements of the 1970s and 1980s included outtakes of a supposedly drunk Welles slurring his way through the ad copy, according to the New Yorker. The possibility that he might have been tired, overly medicated, or simply too grouchy to play along shilling wine on television doesn't really matter, at least not for people who prefer to laugh at the commercial takes today.

Another set of outtakes from a frozen pea commercial underscore Welles' difficulty relinquishing control even while doing hack work. Why should he care about the setting and story for an ad that was just trying to get housewives to throw a particular brand of peas into their shopping carts? But, as Mental Floss reports, Welles cared anyway. Of course, he could have also backed off somewhat and consented to multiple takes, as the beleaguered audio engineer asked him to do in the recording.

Even the commanding baritone of Orson Welles doesn't sound terribly respectable when he's railing about grammar rules and calling the commercial directors "pests." Instead, Welles comes off as a petty tyrant when, just maybe, he could have played along for once and quietly collected his check at the end. But that just wasn't Orson.

Orson Welles was a workaholic

Welles worked himself to the bone on many of his projects, sometimes even resorting to sleeping in theaters (when he slept at all) and doing grueling retakes and reshoots for his films, according to Vox. Consider an early-career Orson Welles, who was directing a staging of Macbeth in New York City in 1936. He would work on the radio from 9 to 6, a perfectly normal workday for most people. Yet, Welles would then rehearse until midnight, travel to the theater where Macbeth was playing, take an inhumanly short nap, and then rehearse some more until the sun broke. At some point, he would shower and then simply continue working.

At time, Welles seemed almost frantic to avoid the specter of laziness, continuing on in a near-berserk pace even as he aged and his body surely reacted poorly to the lack of sleep and occasional amphetamine use (via Chicago Tribune).

Yet, for Welles, it may not have mattered. He freely admitted that there was little separating his work and his life. "I don't know how to distinguish between the two," he later said (via Brain Pickings). Yet, while that may be admirable from a passionately artistic perspective, the real humans in Orson Welles' life may have felt utterly left out by his work ethic. Who was more important, his daughters might have wondered, them or dad's latest film?

Welles left behind a ton of unfinished films

At the time of his death in 1985, Welles left behind a large number of unfinished film projects. These are perhaps one of the most tragic details of Welles' life, given how the complicated, difficult filmmaker was so intensely devoted to his work. They were also, as the British Film Institute notes, mostly independent projects that reflected the endless, lifelong war of creative control that Welles waged with other film studios. One of the oldest projects was a 1939 adaptation of Joseph Conrad's novella, Heart of Darkness, while Welles had been more directly working on a 1980s film version of King Lear when he died.

Some of these attempts are little more than enigmatic fragments, like the test footage for Heart of Darkness. Others were close to completion, like the film that would be released as The Other Side of the Wind in 2018. Quite a few were incredibly frustrating simply because we never got to see the completed project, says Vulture, like the on-again, off-again Don Quixote film that Welles started in 1955 and was still talking about revisiting decades later. He never got the chance to finally finish it.