The Tragic True Story Of The Hillsborough Disaster

April 15, 1989 should have been a thrilling day for fans of Liverpool Football Club. The team was playing Nottingham Forest in the semi-final of the prestigious FA Cup. The match was being held on neutral ground, at Sheffield Wednesday's Hillsborough Stadium, where the teams had also played in the previous year's semi-final. Back then, there had been complaints about crushing in the so-called pens, and in 1981, 38 spectators had been injured.

In the '70s and '80s, concerns about brawls and pitch invasions had driven stadium owners to divide standing terraces into sections (pens) with metal fences. It wasn't uncommon for fans to get jostled and squeezed. But several horrifying mistakes meant the situation at Hillsborough in 1989 became deadly.

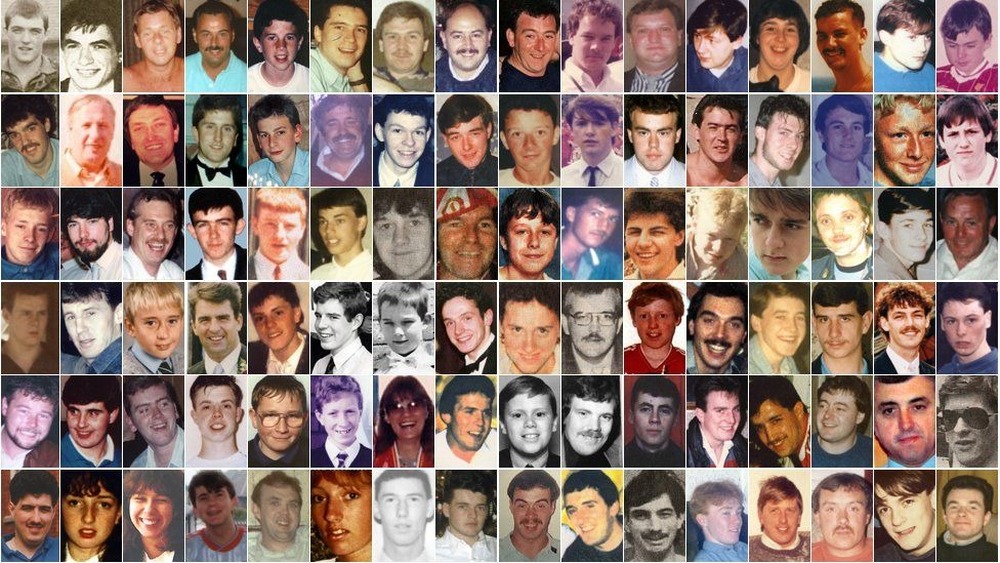

The atmosphere early on was jovial. Survivors would later recall the juxtaposition of the glorious sunny day as people died around them. By the end of April 15, 94 would be dead. Two more would later die of their injuries, hundreds would be hurt, even more traumatized, they would all be blamed, and families would spend 30 years exposing the horrifying truth of what really happened at Hillsborough.

The Liverpool fans were packed into pens three and four

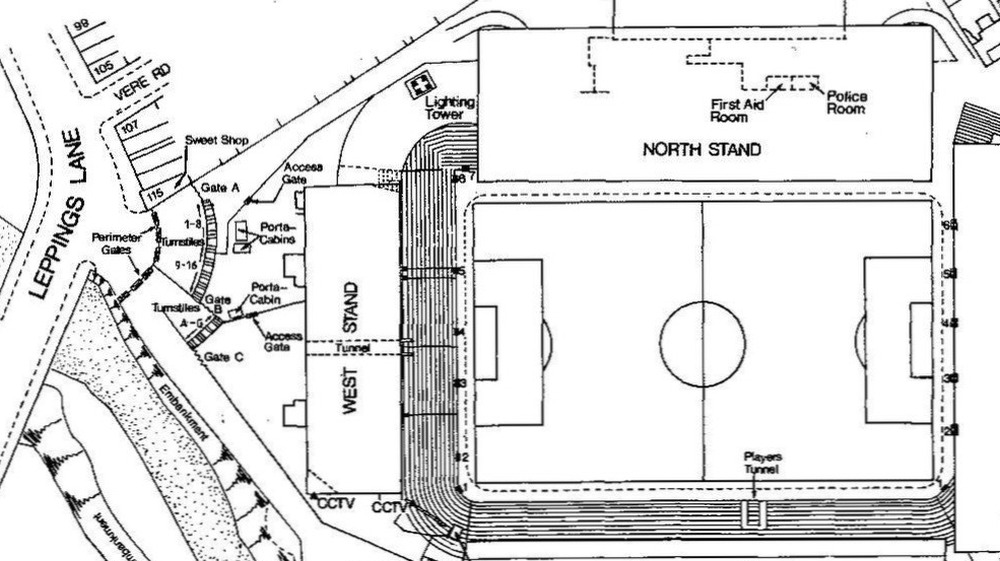

As is standard, the two teams' fans were separated in the stands: Liverpool in the western and northern ends, and Nottingham Forest in the east and south. According to the BBC, 10,100 Liverpool fans had tickets for the western end, on Leppings Lane: a general admission standing terrace separated into six "pens" by 6ft metal fences. There were also 10ft spike-topped metal fences between the pens and the pitch, broken up with a narrow gate in each pen. The match commander, Chief Superintendent David Duckenfield of South Yorkshire Police, was stationed in the police command box, which looked directly onto the pens.

The Leppings Lane terrace was accessed by only seven turnstiles, which led into a small holding area, next to exit Gate C. The holding area channeled into a tunnel, which led directly into pens three and four, behind the goal. There were four other pens, but it was unclear how to access these from the holding area, and no one was directing the fans.

Kickoff was at 3pm. By 2:45pm, 5,531 fans had passed through the turnstiles into the terrace. Over 4,000 were still outside, crammed tightly around the turnstiles and in the holding area. The police were worried about fatal crushing. Duckenfield decided not to postpone the match, which had been done before, but at 2:52pm, he authorized the opening of Gate C to relieve pressure outside the turnstiles.

The situation escalated fatally

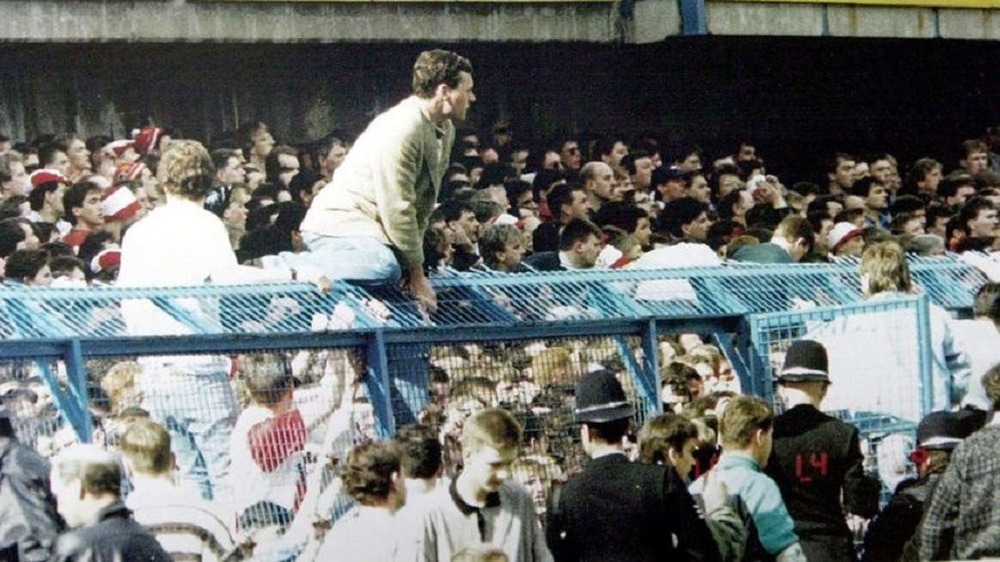

Over five minutes, the BBC reports, 2,000 people headed into the tunnel, and the already-full pens three and four. People were crushed against the fence at the front, and against each other. Survivor Neil Fitzmaurice told the History Channel: "We knew something really, really bad was happening, but the police weren't getting it." Survivors describe feeling the breath being forced out of their bodies, and fighting to stay conscious while people collapsed and died right next to them. Fans in the adjacent pens — some of whom had friends and family in pens three and four — tried to alert police to the growing danger, but were ignored.

The match was finally stopped at 3:06pm, but many officers were still slow to respond. The gate to the pitch in pen three was still locked. People climbed over the fences to the other pens and onto the pitch, and passed others over them. Anyone who fell to the floor was trampled: Survivors recalled feeling bodies beneath their feet. The front of the pens piled up with dead people.

Soon the pitch was covered with the dead and dying. One ambulance arrived at the pens at 3:14pm, but police made the other 41 wait outside. Only one more reached the Leppings Lane end. Witnesses accused some officers of pushing fans back into the pens, refusing to help break down the fences, and of doing nothing to help the injured.

South Yorkshire Police blamed the fans

The BBC puts the final official death toll from Hillsborough at 96. Of those, 38 were children or teens: the youngest victim, Jon-Paul Gilhooley, was 10. Since it happened at a major sports event, the incident had been broadcast live on TV. The initial public response was horror and sympathy, but some in South Yorkshire Police immediately tried to blame the fans, painting them as drunken hooligans who had defied police orders and caused the chaos.

Even as the disaster was going on feet from where he stood, Duckenfield told FA Chief Graham Kelly that fans without tickets had broken down Gate C and caused the surge. Some officers spread unfounded rumors to each other and newspapers that the Liverpool fans had pickpocketed the dead and urinated on police. Notorious tabloid The Sun published these lies under the headline "The Truth," just four days after the disaster. It later emerged that the police had taken an inventory of the dead peoples' belongings, so they knew that no wallets had been stolen.

In fact, in many cases, it was the fans who had performed first aid and carried the wounded to the ambulances, and the dead to the makeshift morgue in the stadium's gymnasium, using advertising boards as stretchers. Families of the dead recalled that when they went to claim their bodies, some police were openly hostile, showing them graphic Polaroids of the bodies, and asking how much alcohol their relatives had drank.

The original report condemned the police

Four months after the Hillsborough disaster, in August 1989, Lord Justice Peter Taylor, who was heading the government's inquiry, released an interim report that condemned police actions as the primary cause of the disaster. In particular, Taylor blasted Duckenfield's decision to open Gate C without blocking off the tunnel leading into pens three and four, describing it as "a blunder of the first magnitude," according to the Guardian. Taylor also criticized the South Yorkshire Police for refusing to accept responsibility for the mistakes it made on the day, and for continuing to blame the fans.

When the full report — known as the Taylor Report — was released a few months later, in January 1990, it doubled down on these conclusions. It also forced all teams in the top two divisions to remove standing room-only terraces, and provided £31m a year in funding to assist in these efforts. This made watching games much safer, although it also eventually led to price increases.

Despite the findings of the Taylor report — and South Yorkshire Police chief constable Peter Wright's public acceptance of them — the Crown Prosecution Service ruled that there wasn't enough evidence to prosecute anyone involved in the disaster, including the stadium owners and the South Yorkshire Police. Yet two months later, the latter admitted negligence when settling civil claims with survivors and families.

The Hillsborough coroner's inquest became infamous

The coroner in charge of the original inquest, Dr. Stefan Popper, was the local coroner for South Yorkshire. On the day of the disaster, according to the Guardian, he ordered blood alcohol level tests on every body in the morgue — including the children — and for the injured in hospital. Families saw this as an endorsement of the police story that the disaster was caused by drunk fans.

Over the next few months, Popper held mini-inquests. He didn't call witnesses except police officers, who testified where and when each person died. This information was not included in the main inquest, which opened on November 19, 1990. The main inquest did hear from witnesses, including survivors, but didn't call on medics who were at the scene. Popper had come to the conclusion that everyone who died at Hillsborough had already been fatally injured by 3:15pm, and refused to hear any evidence that took place after that time.

This decision meant the jury didn't hear evidence detailing how the police and medical response could have contributed to the loss of life. Medics and police later publicly described the first aid response as ineffective and chaotic. There were no defibrillators, oxygen tanks were empty, people were being declared dead by non-medical personnel, and people were left on their backs instead of in the recovery position.

On March 28, 1991, the jury reached a 9-2 verdict of accidental death, effectively saying no one was to blame.

The families and survivors pushed back against the coroner's verdict

By the time the jury returned its accidental death verdict, the survivors and families of those who had died had already realized that they would have to fight to get justice. The South Yorkshire Police and various Conservative politicians and media outlets had been spreading the lie that drunken fans were to blame ever since the crush happened. But hearing the verdict was still a shock: it effectively meant no one would face consequences for the tragedy at Hillsborough.

The families tried to push back. In May 1989, during the proceedings for the Taylor inquiry, they had formed an informal group that they later officially named the Hillsborough Family Support Group (HFSG). This group only included the bereaved families: it did not include survivors who hadn't also lost loved ones. This eventually caused tensions, but the HFSG became the primary voice calling for justice.

After the verdict was released, six families appealed to the High Court on behalf of all the bereaved. They asked the court to throw out the coroner's verdict, on the basis that Popper's 3:15pm cut-off time meant that the inquiry hadn't been properly conducted. In November 1993, Lord Justice McCowan rejected the appeal, concluding that Popper's inquest had been sound.

A 1996 documentary forced the government to investigate again

In 1996, British network ITV aired a dramatized documentary called Hillsborough, written by filmmaker Jimmy McGovern with research by journalist Katy Jones. Watching actors in a dramatic reconstruction of the actual incident, based on witness testimony, demonstrated the horror of the crush in the pens in a way that the grainy footage of the real disaster had not.

The film also laid out details of the newly discovered police cover up, and the families' fight for justice. Criminologist Phil Scraton and the real families and survivors had learned that junior police officers' statements had been doctored by South Yorkshire Police to hide the truth about their chaotic response. The full extent of this cover-up would only be revealed nearly two decades later.

According to the BBC, the combined outcry forced the reluctant government to reexamine Hillsborough. Home Secretary Jack Straw initiated a Judicial Scrutiny of Evidence, which opened in 1997, presided over by Lord Justice Murray Stuart-Smith. From the start, the families felt that the government representatives were against them. That year, a note from Straw was uncovered, in which Straw and then-Prime Minister Tony Blair questioned the "point" of further investigations.

After hearing about the doctored police statements, Stuart-Smith ruled that the changes had been unwise but did not provide enough new evidence to warrant a further investigation, or overturn the coroner's verdict. Straw agreed with his findings.

The families tried to hold Duckenfield responsible

David Duckenfield had been appointed Chief Superintendent of the South Yorkshire Police just 19 days before the disaster. He had no experience managing soccer matches, let alone an FA Cup semi-final. He was the one who authorized the opening of Gate C, and then lied that the fans had broken it down — something he didn't admit until 2015, the BBC reports.

Duckenfield was supposed to face an internal investigation, alongside Superintendent Bernard Murray. Murray had been in charge of the police control box at Hillsborough, where he stood with Duckenfield as the disaster unfolded, with a direct view of the crush. But Duckenfield escaped those proceedings when he retired in 1991, on medical grounds, which also allowed him to receive his full pension. Subsequently, the South Yorkshire Police decided that it would be unfair to investigate Murray alone.

In August 1998, after Jack Straw had declined to open a new public inquiry, the Hillsborough Family Support Group (HFSG) initiated a private case against Duckenfield and Murray, charging them with manslaughter. At trial in 2000, the jury found Murray not guilty and couldn't reach a unanimous verdict on Duckenfield. The judge ruled that Duckenfield would not have to go to a retrial.

The families kept fighting

From the moment they were shown into the stadium's makeshift morgue, the families of the dead understood that they would have to shoulder the burden of getting justice for them. Over the next three decades, they traveled up and down the country, attending inquests where they saw graphic images of their loved ones' deaths. They raised awareness and legal funds to keep fighting. Some even dug up evidence of their own.

Anne Williams' 15-year-old son Kevin Williams died at Hillsborough. She was part of the group that appealed against the original verdict in 1993, which also filed three more appeals with the attorney general, all of which were rejected. According to the Guardian, Anne had tracked down two witnesses — off-duty police officer Derek Bruder and special police constable Debra Martin — who both said that they saw signs of life in Kevin after 3:30pm. This would invalidate the 3:15pm cut-off at the original coroner's inquest. Anne also found a pathologist who testified that Kevin could possibly have been saved if he'd received proper medical treatment in time.

In 2009, Anne filed an appeal with the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), arguing that she had exhausted all domestic measures for getting justice. The Liverpool Echo wrote that her case was rejected because the ECHR ruled that she had missed the deadline to file, which had expired six months after the 1997 Scrutiny of Evidence. Anne Williams died of cancer in April 2013.

A new inquiry finally revealed the truth

In 2009 — the 20th anniversary — calls for an independent investigation reached a critical mass, forcing the government to act. The Hillsborough Independent Panel was formed the following year. According to the Guardian, it reviewed 450,000 pages of documents, before presenting its findings in a report in September 2012. The panel revealed the extensive police campaign to alter officers' statements so they favored the police while blaming the fans. It also found that 41 of the 96 who died had different injuries than the ones laid out in the original pathology reports, and could potentially have been saved if the police and medical responses had been more effective.

Then-Prime Minister David Cameron formally apologized to the families in Parliament, for the loss of their relatives and for the delay in exposing the truth. The government and the Independent Police Complaints Commission initiated criminal investigations, but the inquests didn't start until 2014. In December 2012, the High Court threw out the accidental death verdict.

Finally, after spending 267 days hearing evidence, in April 2016 the jury returned a 9-2 verdict that stated the 96 victims had been unlawfully killed. It also specified that the fans had done nothing wrong, blamed the police for causing the disaster by failing to control the crowd, and blamed the police for contributing to loss of life by failing to respond effectively.

David Duckenfield went on trial again in 2019

In 2015, when questioned as part of the inquiries following the Hillsborough Independent Panel's report, Duckenfield admitted to the jury that he had lied about fans breaking down Gate C. According to the BBC, he said that police by the turnstiles were telling him over the radio that people were going to die if he didn't open the gate — so he did. He also said he didn't know that the layout of the Leppings Lane terrace meant the people heading through the gate would go directly into pens three and four. He said his mind "went blank" as the disaster unfolded in front of his eyes.

Two years later, the Crown Prosecution Service announced plans to prosecute Duckenfield for manslaughter by gross negligence of 95 people. (The 96th Hillsborough victim had died four years after the disaster, outside of the statute of limitations, when his life support machine was switched off in 1993.) CPS threw out the earlier ruling that Duckenfield could not be tried again.

The trial started in April 2019, and included harrowing testimony from survivors, families of the dead, and police officers who were at Hillsborough. That jury failed to reach a verdict, but at a retrial that November, another jury found Duckenfield not guilty. The families were horrified that no one would be held criminally responsible.

Survivors still feel the trauma of Hillsborough

Over three decades since 96 people died because they went to a soccer match, their families and hundreds of survivors still live with the trauma of that day. Many of the survivors were also the ones administering first aid. They were subjected to aggressive police interviews about their drinking habits and behavior. Later they provided key testimony at the various inquiries. But some feel they've been overlooked.

According to the Washington Post, 766 people were injured: but even people who escaped physically unscathed suffer from emotional scars. Many who survived the pens also lost someone that day, adding to feelings of survivor's guilt. Joseph Glover survived Hillsborough, but his younger brother Ian died, despite Joseph's efforts to resuscitate him. In 1999, Joseph told the Guardian that he'd spent years sleeping on Ian's grave, "to be with him." His is just one of hundreds of heartbreaking stories. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is also common. Survivor Neil Fitzmaurice told the Liverpool FC website in 2009 that after the disaster, just wearing tight clothes felt too much like being crushed. He couldn't sleep, and still struggles in crowds.

Even talking about what happened was hard. Macho soccer culture didn't help, and survivors felt like people who weren't there couldn't understand. They mainly turned to each other. Fitzmaurice recalled that Hillsborough survivors would gather in a pub near their home stadium. "It was just thousands of lost souls," he said.