The Unsettling History Of Government-Sponsored Abductions

Although renditions existed well before September 11, 2001, after 9/11 the U.S. government started calling them extraordinary and in the words of Cofer Black, director of the CIA's Counterterrorism Center, the gloves came off. Rather than abducting someone for the purpose of putting them on trial, no matter how farcical it was, the CIA started working with foreign countries in simply detaining people suspected of terrorist links. They're always presumed guilty, they're always denied due process, and they're almost always tortured.

However, the Bush administration didn't come up with this program. The act of abducting people dates back to the 1800s and renditions as we know them started to form during the Clinton years.

Now, while the CIA claims to have ceased its program of extraordinary rendition, it continues to maintain detention centers like Guantanamo Bay. There, many await trials that are perpetually delayed. This is the unsettling history of government-sponsored abductions.

What is extraordinary rendition?

Extraordinary rendition is recognized as the act of kidnapping and transferring people without due process to a foreign government, often where they are abused and tortured during interrogations. The act of abducting someone deemed a criminal has a long history in the United States, although initially the act of rendition involved abducting someone in order to prosecute them. In the 1886 U.S. Supreme Court Case Ker v. Illinois, the court ruled that the kidnapping of Frederick Ker from Peru without proper use of the existing extradition treaty "did not violate the U.S. Constitution."

In 1952, this idea was upheld in Frisbie v. Collins, which maintained that if "a person was forcibly abducted and taken from one state to another to be tried for a crime [that] does not invalidate his conviction in a court of the latter state."

However, these abductions differ from the extraordinary rendition of the 21st century. While the Reagan, Bush Sr., and Clinton administrations abducted people for the purpose of putting them to trial, the Bush Jr. administration changed their tactics. According to "Extraordinary Renditions in the Fight Against Terrorism," this strategy "included the holding of presumed terrorists in recognized or secret detention centers that were controlled by the U.S. but located outside its territory, and managed by third-party countries 'representing' the United States." Often, there's no intention of putting someone on trial. The aim is only imprisonment and interrogation.

Methods of transport

The CIA uses front companies in order to purchase planes that they use to transport kidnapped people during extraordinary rendition. Dozens of aircrafts have been linked to the CIA and extraordinary rendition.

According to the Business & Human Rights Resource Center, the ACLU even filed a lawsuit against Jeppesen Dataplan in 2007 for its participation in extraordinary renditions. The ACLU alleged that Jeppesen Dataplan, a subsidiary of Boeing, knowingly engaged extraordinary rendition flights and "aided and abetted the torture and inhuman treatment they suffered and allege Jeppesen's complicity in the violation of customary international law." Before Jeppesen even had a chance to respond, the U.S. government swept in and put in a motion to dismiss the case. And it worked. SFGate reports that in 2008, the lawsuit against JD was dismissed since the federal judge agreed "with the Bush administration that the case risks exposure of state secrets."

And if you can believe it, sometimes the CIA even sells off the jets that they used for extraordinary rendition. In 2017, Mother Jones reported that the Boeing 737 N313P was on sale for a mere $27.5 million. Although the listing didn't mention the plane's infamous history, its tail number had been tracked before.

'Black sites'

When people are kidnapped and experience extraordinary rendition, the CIA takes them to one of their many "black sites." Black sites are CIA prisons that exist in up to eight different countries and there's evidence for at least 20 black sites across the globe. The use of the term "black sites" was first revealed in 2005, but people were aware of secret CIA detention facilities as early as 2002. These black sites aren't used simultaneously. Instead, "these facilities tend to be used in rotation, with detainees transferred from site to site together, rather than being scattered in different locations," writes Amnesty International.

According to The International Journal of Human Rights, black sites, especially those in Europe, "did not exist in isolation from one another, nor from prisons elsewhere in the world. Rather, they formed part of a global network of detention facilities, connected to one another through hundreds of 'rendition flights' by civilian aircraft, operated by or on behalf of the CIA."

The United States government has also repeatedly made systematic attempts to suppress knowledge about extraordinary rendition and the black sites, often redacting relevant information or inserting pseudonyms. The CIA claims that they closed all the black sites in 2009, but there's evidence of people being held long after the black sites were claimed to be shut down. Most extraordinary renditions occurred between 2001 and 2009, and although no one knows the total number, it's speculated to be "several hundred."

'Enhanced Interrogation techniques'

At the black sites, people are subjected to "enhanced interrogation techniques," which is what the United States government calls torture. Globalizing Torture writes that these techniques ranged from waterboarding, stress positions, and cramped confinement to sleep deprivation and "dietary manipulation."

CIA documents are also vague on the torture, stating only that people were "subjected to an initial round of 'enhanced interrogation techniques' at BLUE." While the CIA has what it considers to be authorized enhanced interrogation techniques, there's little oversight as to what actually occurs in the black sites. According to The International Journal of Human Rights, at a black site in Poland, Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri was subjected to "unauthorized 'enhanced interrogation techniques,' such as mock execution, threats of torture with a power drill, threats of familial rape, and 'bathing' with a stiff brush in a technique designed specifically to cause pain."

Extraordinary renditions essentially allow the CIA to torture people without technically getting their own hands dirty: "Extraordinary rendition was intended to outsource abusive interrogations." And although the United States government has claimed that they don't abduct and knowingly transport people to countries to be tortured, there's little oversight on their part. A U.S. official admitted as much when they said, "We don't kick the sh*t out of them. We send them to other countries so they can kick the sh*t out of them."

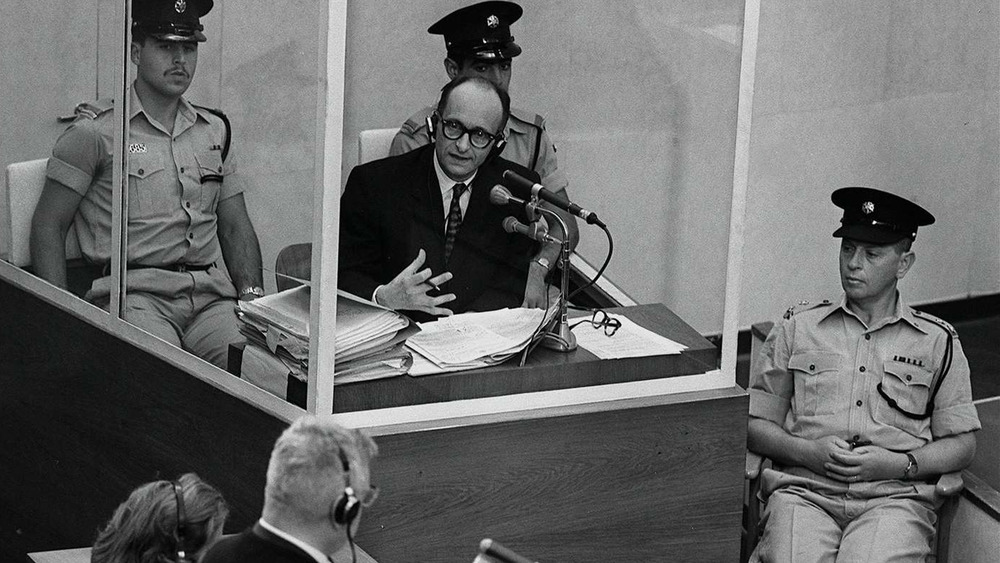

Israel's rendition of Adolf Eichmann

One of the most famous historical government sponsored abductions was the rendition of Adolf Eichmann. However, as with the renditions before September 11th, this rendition was done with the intent of putting Eichmann on trial for his crimes during the Holocaust. Eichmann served as one of Hitler's organizers for the "Final Solution," but after the war Eichmann escaped and fled to Argentina, according to The Guardian. For a time, Eichmann managed to keep his identity a secret and lived under the name Ricardo Klement. But when Eichmann's son started dating the daughter of a Holocaust survivor, her mother became suspicious and alerted Mossad, the Israeli intelligence agency.

Eichmann was abducted on his way home from work in May 1960. Once his identity was confirmed, Israeli intelligence agents came up with "an elaborate plan to spirit him out of the country without alerting the Argentine authorities." According to NPR, a doctor was also brought to administer sedatives to Eichmann, in order to make him look like a sick Israeli flight crew member. Eichmann was taken to Israel where he stood trial and was sentenced to death. He was executed on May 31, 1962, "the only time in Israel's history that the death penalty has been enacted."

This also wasn't the first time that Mossad agents had kidnapped and drugged someone. In 1954, Mossad agents captured Alexander Israel, but the sedatives they gave him ended up being fatal.

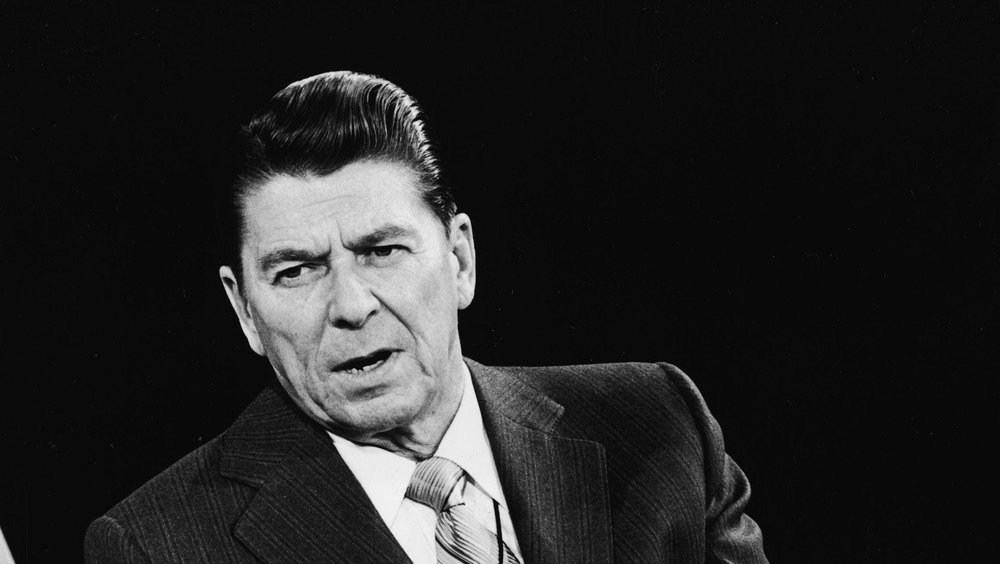

The U.S. rendition of Fawaz Younis

In 1986, the Regan administration carried out one of its first government sponsored abductions. According to Slate, this plan became possible because President Reagan signed "a secret covert-action directive in 1986 that authorized the CIA to kidnap, anywhere abroad, foreigners wanted for terrorism." Globalizing Torture also notes that the directive only authorized renditions from places "where the U.S. government could not secure custody through extradition procedures." Authorizing "renditions to justice," this appears to be the first time that renditions are named as such.

The target of the joint FBI-CIA operation known as "Operation Goldenrod" was Fawaz Yunis, who had participated in an airplane hijacking on June 11, 1985. Although no one had been killed, there were "at least two American citizens" on board. After the FBI got their arrest warrant, back when there was a bare adherence to due process, on September 13, 1987, Yunis was lured onto a yacht by undercover FBI agents in Cyprus under the guise of a drug deal. But instead, once the boat reached international waters, Yunis was arrested.

According to the Military Law Review, during the arrest, FBI agents "fractured both of Yunis' wrists, although medical personnel did not diagnosis or treat the injuries until much later." Yunis also wasn't informed of his rights until he arrived in the United States days later. In Washington, D.C., Yunis was convicted of "conspiracy, hostage taking, and air piracy" and was sentenced to 55 years total.

Extraordinary rendition under Clinton

Under President Clinton, the United States continued the policy of rendition that the Reagan administration had initiated. According to Globalizing Torture, it's estimated that 10 renditions occurred between March 1993 and September 2001. However, former CIA Director George Tenet claims that "the CIA took part in over 80 renditions before September 11, 2001."

In "Extraordinary Rendition and U.S. Counterterrorism Policy," Mark J. Murray writes that "the extraordinary rendition program in its current incarnation began in 1995 during the Clinton Administration." But during this time, not only was presidential approval required, but people who were abducted or kidnapped "were only to be transferred to countries where they were wanted for a criminal offense."

Egypt was one of the first countries recruited into the extraordinary rendition program. Several people who had been rendered to Egypt, including Tal'at Fu'ad Qasim, disappeared soon after or were "subjected to the death penalty after unfair trials." Although the Clinton administration claimed that foreign governments had promised no one was going to be tortured, it's "questionable" whether or not these claims are true or were complied with. According to Mother Jones, during the Clinton administration there were "14 documented extraordinary renditions," almost all of whom went to Egypt.

Expansion of extraordinary rendition after 9/11

After the 9/11 attacks, extraordinary rendition took on its current form, although it should be noted that technically the U.S. government has never given a publicly available official government definition of the practice. Regardless, the CIA was authorized by President Bush to create black sites, lifting the restriction that people were only to be kidnapped if they were to be taken to a country where they were pending trial. Between 2001 and 2005, the United States executed at least 70 extraordinary renditions, although some estimates are as high as 150.

The extraordinary rendition program, or the RDI program, that began after 9/11 differed from previous renditions. "Partners in Crime" explains that "prior to 9/11 high level U.S. officials did not make public statements in support of torture." And while the United States had previously kidnapped people "outside the legal extradition process," this rendition typically resulted in prosecution, even if done as a farce in another country.

After the 9/11 attacks, U.S. personnel were now allowed a role in interrogations and were suddenly singing the praises of torture. According to Violent Geographies, in 2003, lawyers for the Defense Department claimed that "the president wasn't bound by laws prohibiting torture and that government agents who might torture prisoners at his direction couldn't be prosecuted by the Justice Department."

The worst vacation

The United States government has often justified extraordinary renditions because they claim that people are guilty. However, extraordinary renditions presume guilt without a trial and are in their nature fundamentally flawed. And unfortunately, the United States government has shown little regard for whether or not someone is actually guilty of anything, as in the case of Khaled El-Masri.

In 2003, El-Masri was abducted by the CIA while he was on vacation in Macedonia. A Lebanese-born German citizen, El-Masri was actually picked up in a case of mistaken identity. But despite realizing this early on, U.S. agents detained and tortured El-Masri for six months in Afghanistan, according to "Extraordinary Rendition and U.S. Counterterrorism Policy": "Instead of developing a coherent repatriation plan with German authorities, the United States proceeded in secret to destroy any evidence of his actual detention and left him for dead in the middle of nowhere."

El-Masri was suddenly released in 2004 "in Albania on the side of a mountain." Upon returning to Germany, El-Masri filed a suit against the United States, but the ACLU reports that "the Bush administration pressed the Supreme Court to refuse to hear El-Masri's case." However, the European Court of Human Rights found Macedonia guilty of violating El-Masri's rights.

Some estimate that dozens of people may have experienced "erroneous renditions," where the wrong person was abducted based on bad intelligence.

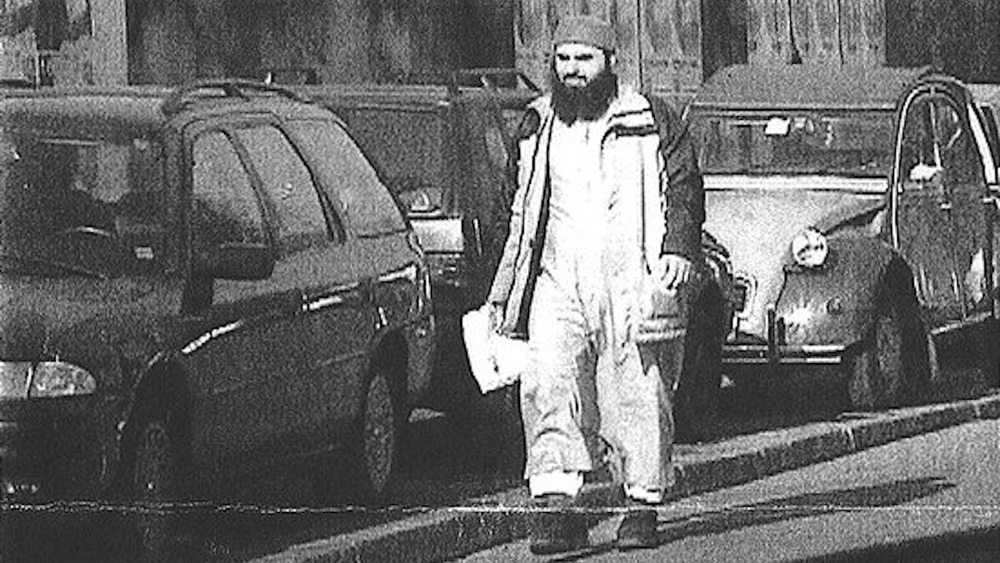

The abduction of Abu Omar

Hassan Mustafa Osama Nasr, also known as Abu Omar, was abducted near his home in Milan, Italy on February 12, 2003 in the middle of the afternoon. Slate writes that Nasr was approached by police, drugged, and then flown via Germany to Egypt. There, Nasr was imprisoned for over a year and tortured repeatedly. Mother Jones reports that despite being tortured and interrogated about the Islamists he knew in Italy, "every now and again [the interrogators would] indicate that they knew [Nasr] wasn't a big-time terrorist. They were detaining him only because 'the Americans imposed you on us.'"

After a court in Cairo determined that Nasr wasn't involved in any terroristic activity, he was released after being detained for 14 months. However, "[Nasr] was told not to contact anyone in Italy—including his wife—and not to speak to the press or human rights groups. Above all, he was not to tell anyone what had happened."

Despite these instructions, Nasr promptly called his wife. However, it took him three weeks to admit what had happened to him. And within a month of his release, Nasr was arrested and imprisoned once more. After three years, he was released again in February 2007, but this time confined to house arrest in Alexandria.

Trial in Milan of CIA agents

During his time in captivity, Hassan Mustafa Osama Nasr reached out to Italian magistrates, and upon his release Deputy Chief Prosecutor Armando Spataro took his case. Although Nasr had once more been ordered to keep quiet, "the pursuit of the legal case meant that he didn't have to."

Italian judges were initially just investigating the illicit activity of CIA agents, who did not cover their tracks well. Italian police found numerous documents during raids, and some agents "didn't even use false names, which made it extremely easy for the magistrates to identify personnel captured on closed-circuit cameras," according to "Extraordinary Rendition and U.S. Counterterrorism Policy."

However, during the course of the investigation it was discovered that the SISMI, the Italian military intelligence agency, also actively cooperated and participated in the abduction. Initially, the extradition of 22 CIA agents was requested, but this was revised to 26 agents in December 2006. Eight SISMI agents were also charged, as was a journalist who was "being paid to distribute misleading information."

NBC News reports that in 2009, the Italian court found two Italian agents guilty and 23 Americans guilty in absentia. These were "the first convictions related to the extraordinary rendition program by any foreign government." All of the American agents convicted are the subjects of outstanding arrest warrants. Nasr and his wife were awarded over $1.5 million in damages.

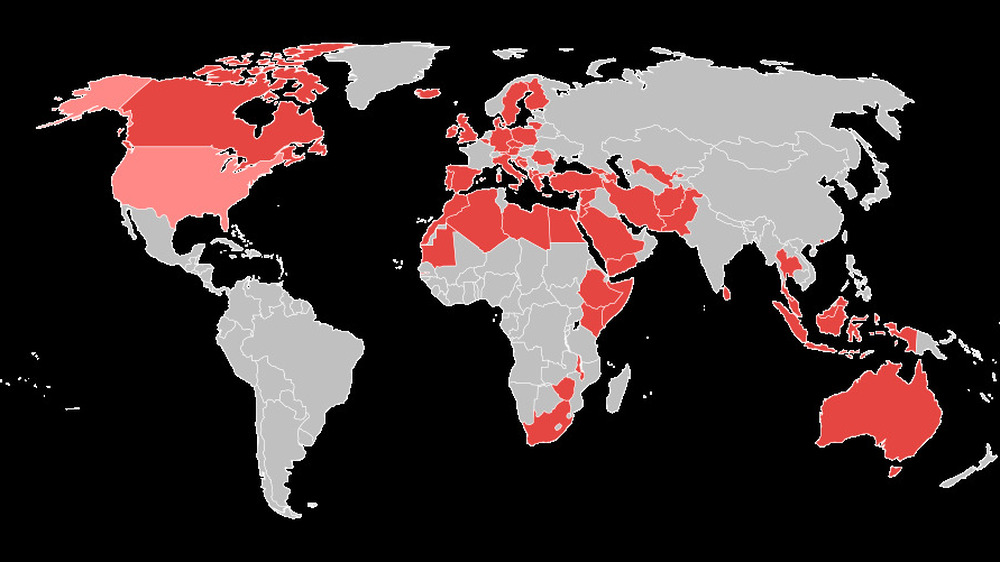

Extraordinary rendition worldwide

Although many black sites closed under the Obama administration, places like Guantanamo Bay detention camp remain open. And as NPR notes, Guantanamo's legacy of torture has become "a major reason there has still been no trial — and may never be one — for alleged Sept. 11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and other Guantánamo prisoners."

During its peak, over 50 countries participated in the CIA's extraordinary rendition program. But when all the black sites were supposedly closed, it's unclear what happened to all the people who were being detained.

The United States isn't the only country that abducts people and subjects them to extraordinary rendition. Numerous countries, such as Turkey and Saudi Arabia, also engage in extraordinary rendition of their own. According to Foreign Policy, in 2018, the Saudi government claimed that the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi was intended to be an extraordinary rendition for the purpose of detention, rather than an outright execution.