Everyday Inventions Everyone Hated At First

New technology ending in disaster has been a recurring theme, or at least a major plot point, of thrillers and science fiction for decades. "Scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could," said Jeff Goldblum in Jurassic Park, "that they didn't stop to think if they should." And the fictional chaos theoretician there had a point, which is widely applicable to the world. Certainly Alfred Nobel thought so, as he invented dynamite and spent the rest of his life trying to atone for it.

Just as often as they are reckless however, humans are obstinate towards very safe, practical inventions. Harvard University professor Calestous Juma told The Washington Post that while some people resist change naturally, some do "because innovation often means losing a piece of their identity or lifestyle." Some of the things you use every day were once a menace to society.

Nobody liked cars at first

In many ways, cars made a significant impact on American culture. The road trip, both as an activity and as a narrative genre, is quintessentially American. Highway 66 attracts tourists from all over the world. American classic car clubs are present in almost every country in the world. It took decades for the car to catch on though.

For one, cars used to have competition. Long distance trips were far easier and cheaper on the trains and steamships that were springing up all around the country in the 19th century. Asphalt-covered streets were a few decades in the future, explained a contemporary of Henry Ford in the Saturday Evening Post in 1930, "No paved highways for automobiles to shoot along at 60 and 70 miles an hour; just country roads, filled with ruts, sand, and mud, over which no one wanted to drive at the maximum speed of passenger cars." There were also no gas stations, and drivers would buy gasoline by the pint, quart, whatever they could find.

Then there was the noise and dust created by the "horseless carriage." They scared horses and irritated pedestrians. There were no stop lights, no speed limits, and cars were so reviled that, The Detroit News describes, "The state of Georgia's Court of Appeals wrote: 'Automobiles are to be classed with ferocious animals...'" As Bloomberg reports, anti-car protests continued in the states well into the 1960s.

Public shaming awaited any Englishman carrying an umbrella

England has defended against invasions from France since Julius Caesar's legions over 2,000 years ago. The historical antipathy the French and English held for each other ran so deep that in the 18th century, anything French was for many Britons, basically anti-English. In his book, Old and New London, 19th century English journalist Walter Thornbury credited a man named Jonas Hanway for introducing the umbrella to Britain. Being English, Hanway appreciated the utility of a device to keep England's weather off of him. However, while Hanway discovered it in Persia, umbrellas were popular in France, so the English were not having any of it.

"For a time no others ...ventured to carry an umbrella," wrote Thornbury. "Anyone doing so was sure to be hailed by the mob as 'a mincing Frenchman.'" He recounts footman John MacDonald's experience carrying a Spanish umbrella in London in 1770 and being yelled at — "Frenchman, why don't you get a coach?"

An 1883 edition of Gentleman's Quarterly, quoting Scottish author Robert Chambers, postulates that one of the key anti-umbrella groups was taxi and coach drivers who "regarded rainy weather as a thing specially designed for their advantage" and jealous of the competition umbrellas offered. Eventually, mere harassment couldn't keep the English from keeping dry and "in many of the large towns of the Empire, a memory [was] preserved of the courageous citizen who first carried an umbrella."

The Sony Walkman was ruining society

For most of human history, anyone wanting to listen to music needed access to instruments and people who knew how to play them — so most people didn't actually listen to music regularly, if really at all. By the end of the 19th century, with the invention of phonographs and wireless technology, anyone with access to a certain device could listen to music at home. At the end of the next century though, a revolution in music occurred that, according to many people at the time, ruined an entire generation — if not society itself.

In 1979, the Sony Walkman debuted. "It was the first mass mobile device," Rebecca Tuhus-Dubrow, author of Personal Stereo, told Smithsonian Magazine. "It changed how people inhabited public space in a pretty profound way." A profoundly negative way for many. The ability for teens and young adults to turn off the world around them was isolating a generation, making them lose contact with reality, and "The Walkman Effect" was pontificated on by the press, politicians, and even academia. The Walkman was "a symbol of navel-gazing self-absorption." American philosopher Allan Bloom warned of students wearing headphones, "a pubescent child whose body throbs with orgasmic rhythms," too distracted to study. German magazine Der Spiegel described it as "a technology for a generation with nothing left to say."

Bicycles have a long history of being hated

Bicycles can make people angry. Especially city-dwellers. Contrary to popular belief, this is not an American attitude. Even famously bike-friendly Amsterdam has, according to Bloomberg, begun instructing "traffic wardens...to cajole, advise, and (if necessary) threaten cyclists into behaving more sociably." This is also not a new attitude — practically since they were invented, bicycles have faced hostile city laws and a disapproving pedestrian population.

The New York Post explains how, "Velocipedes, as they were called, arrived from Europe in May 1819." The first bicycles had no pedals, were mostly wood, and shared muddy, unpaved roads with "carts, carriages, pedestrians, horses and hogs," wrote James Madison University history professor Evan Friss in his book, On Bicycles: A 200-Year History of Cycling in New York City. Bicycles were seen as mostly a novelty, an annoyance, and subsequently banned in downtown Manhattan the same summer they were introduced to NYC.

At the end of the century, bicycles made a comeback, this time with tires, pedals, metal spokes, and looking much more like what is recognized today as a bicycle. But there was still backlash against it — at least, for a certain half of the population. Women were discouraged from riding bikes for health reasons. "Bicycle face," as Vox explains, was supposed to be caused by overexertion and dangerous for women — nothing to do with the bicycle's growing role in the liberation of women.

People have always protested vaccines

Since prehistory, disease has been, well, a plague on humanity. The ancient Greeks believed that sickness was a result of an imbalance of the body's "humors," and for 20 centuries, basically all remedies were based on re-balancing the humors. It wasn't until around the 16th century, says Nature Magazine, that "Variolation, deliberate infection with matter from smallpox pustules or scabs to bring about natural immunity" began to be practiced in areas of Africa and Asia. Over a century later, Massachusetts preacher Cotton Mather was a proponent, "having learnt it from an African man, Onesimus, enslaved in his household" and was roundly mocked for his ideas on preventing disease.

Towards the end of the 18th century, actual vaccines, delivered by actual physicians, had finally made their way into medical practice. And immediately afterwards, skeptics, according to physiologist Jonathan Berman, criticized vaccinations for reasons that haven't really changed in the centuries since. He explains in his book, Anti-vaxxers: How to Challenge a Misinformed Movement, how vaccines constituted a "foreign assault on traditional order." The power of privilege, says Berman, and fear of social control led to coordinated resistance to everything from Britain's Vaccination Act of 1853 to modern day rejections of the COVID vaccines. He quotes rapper M.I.A. from 2020, "If I have to choose the vaccine or chip I'm gonna choose death."

Pinball was for gangsters and gamblers

Pinball machines evolved, according to Princeton's Joseph Henry Project, from European tabletop parlor games called "Bagatelle" tables. In Bagatelle, players used a stick to shove a small ball into position above a bunch of pins. The ball would bounce down off and past the pins into holes at the bottom with different scores. The electronic version introduced in the early 20th century added bumpers and lights and tilt sensors, but there were no paddles yet, and pinball remained little more than a game of chance.

The pinball machine entered the market just as the Great Depression was getting into full swing and, since it cost only a nickel to play, became hugely popular. The first coin operated pinball was sold in 1931, says Aeon, and just ten years later there were 20,000 in New York City alone. Also happening at the same time was the repeal of Prohibition and a crackdown on gambling. So rum-running gangsters looking for new income, and gamblers looking for an itch converged on pinball. "The main [pinball] distributors and wholesale manufacturers are slimy crews of tinhorns," said New York Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, who joined the mayors of Los Angeles, Atlanta, and Chicago in siccing the cops on pinball. Even after paddles were added in 1947, it took "a pinball wizard named Roger Sharpe" to demonstrate in person to "the New York City Council in 1976 that pinball was indeed a game of skill."

Dairy farmers hated margarine

Margarine was invented, according to National Geographic, because French Emperor Louis Napoleon III needed a cheap butter alternative to feed both his growing navy and France's huge population of poor people. A mixture of beef tallow and milk, margarine didn't sell well until a Dutch company dyed the margarine yellow so as to look more like butter. However margarine was a threat to butter.

To protect their dairy industry, Canada actually banned the production or importation of margarine from 1886 to 1948, with a respite during and immediately after World War I. When it came to the states, American dairy farmers all over the country were incensed and lobbied hard for state and federal laws to protect their business. Margarine was banned in some states, by the turn of the century over half the country prohibited dying dairy products, and a few states even mandated that any margarine sold there had to be dyed an ugly pink color.

As USA Today reports, margarine's reputation is still battered by false accusations of it being unhealthy (it kind of used to be but the recipe changed long ago), that it was invented to fatten turkeys, and that it is "one molecule away from being plastic." Dairy-loving Wisconsin legalized margarine in 1967, but it's still a tough sell there as a hotel director told On Milwaukee, "We don't carry margarine. If guests don't want butter we provide olive oil."

Comic books would turn kids into communists or criminals

The newspaper comic strips that modern comic books evolved from had been around for over 30 years by the time someone decided to publish a colored collection of them in a single 1929 book, The Funnies #1. The next decade would be, according to The Artifice, "the start of the Golden Age of comics." The 1930s saw the birth of all kinds of storylines — cowboy comics, horror comics, space comics, and in 1938, with the introduction of Superman, superhero comics. Comic book sales soared during World War II. But not, says Military.com, "because of kiddies with spare dimes." The people buying comics were young men "being shipped off to war." Some estimates say that GIs requested comic books so frequently that "nearly 30% of reading material sent to deployed soldiers were comic books."

In the 1950s, the best-selling comics were horror and crime stories, often with graphic content, and the industry came under attack by religious and community organizations across America. Princeton University Archives quotes a Chicago reverend's description of comics showing "crime, disrespect for law, rape, infidelity, perversion, etc." Comic publishers and authors and artists were made to testify before Congress. The major publishers got together and created the Comics Code Authority, a voluntary regime of self-censorship that would govern the content and subject matter of comics for most of the next 30 years.

Nobody wanted to ride a driverless elevator

The elevator is actually ancient technology. Pulleys and ropes have been used to build pyramids, temples, and aqueducts for millennia. Two thousand years ago the games in the Roman Colosseum were stocked with animals, according to Smithsonian Magazine, raised up on elevator platforms from the basement to the floor. But it wasn't until the introduction of mechanical elevators in the mid-19th century that they were used to transport people.

The first passenger elevator, CNN says, opened in a five-story building in New York City in 1857. It closed in 1860 because nobody wanted to ride it. Early elevators were steam-powered, often noisy, and generally slow, plus there weren't really any buildings on the planet higher than five stories yet so the elevator remained a novelty for a few years. The invention of the elevator, per the NCBI, was actually necessary for the development of skyscrapers, and soon, incorporating elevator shafts was standard practice in urban America.

For decades elevators had operators but, UNC Charlotte professor of architectural history Lee Gray told NPR, horrific accidents would still occasionally happen even with someone "driving," so when an automatic elevator was introduced, nobody wanted to get on. Thus, for 50 years, elevators had operators. Finally, in response to a New York City elevator operator strike, the industry made the "emergency stop" bright red and launched a massive ad campaign to convince the public elevators were safe.

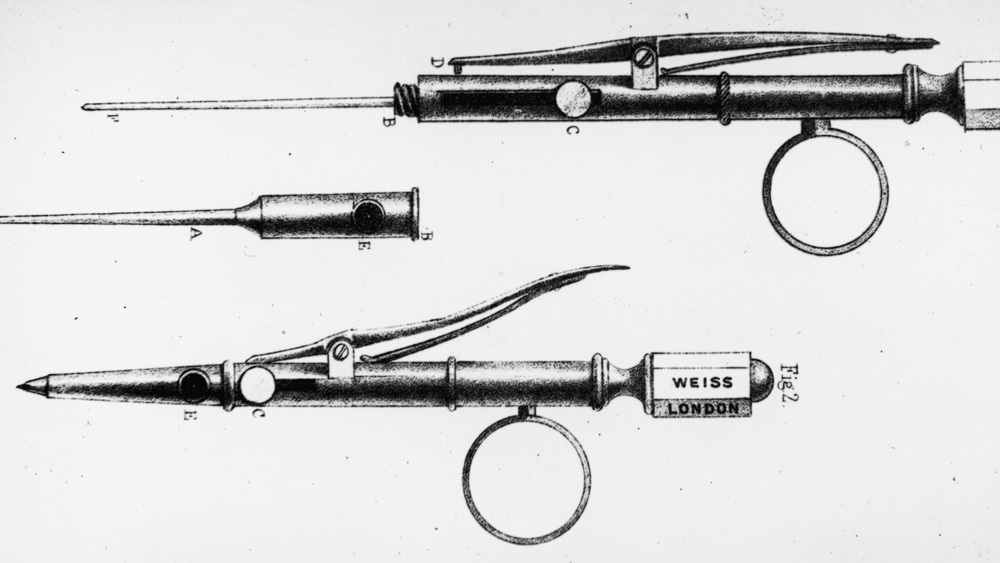

Electricity scared a lot of people

Out of all inventions that make modern life possible, electricity may be the most important. The resistance to electricity was widespread, grounded in fears both reasonable and paranoid.

Completely valid worries of house fires and electrocution were compounded by public misinformation — people thought just turning a light switch could kill them. According to the White House Historical Association, "President Benjamin Harrison and his wife, Caroline, refused to operate them for fear of a shock." University of Texas British Studies Professor Phillippa Levine told NPR that "people had fears that electricity was going to leak out of the walls." The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers described how doctors thought electricity caused "neurasthenia," a nervous system disorder caused by "acceleration of people's lives due to the telephone and telegraph."

One organized group agitating against electrification were from an industry negatively affected by it. The MIT Sloan Management Review describes how urban lamplighters, people whose job it was to light the gaslights on city streets, went on strike or "smashed the electric lamps in fear of losing their jobs." This helps explain another obstacle to electric acceptance. The Institute for Energy Research explains that for the first electric grid, Thomas Edison had to bribe "New York's famously corrupt city government to build his proposed network...He got their approval in part by plying them with a lavish champagne dinner."

Video games were creating a generation of antisocial idiots

Video games entered American homes in the late 1970s and within a decade were one of history's most popular pastimes, as well as a multi-billion dollar industry. By the end of the 80s, gamers and parents of gamers were warned, says Smithsonian Magazine, by "educators, psychotherapists, local government officeholders and media commentators...that young players were likely to suffer serious negative effects."

Like watching television, playing video games was supposedly bad for your eyes. Holding the controllers led to "Space Invaders Wrist." The games were designed to be addictive. They promoted Satanism and violence. Video games were, as the Smithsonian quotes a letter to The New York Times, "cultivating a generation of mindless, ill-tempered adolescents." A Dallas suburb went so far as to ban anyone under 17 from the local game arcade "unless accompanied by a parent or guardian."

By the 1990s, video games were more popular than ever, the graphics were better, and the subject matter evolved. "This was the era of 'Doom,' 'Resident Evil' and then 'Grand Theft Auto,'" notes the Mercatus Center. "The whole world went mad." Bookshelves were filled "with titles like Stop Teaching Our Kids to Kill," while media pundits said the industry was filled with "criminal elements" and that video games were "murder simulators." The first congressional hearings on video games were in 1993, and they have been a regular staple of American political theater ever since.

Novels were corrupting young women

Books may be ancient, but the novel is relatively new. The printing press made printing books cheaper, easier, and more widespread, but it took 200 years before society had evolved to the point where fiction for mass consumer audiences was really a thing that people wrote and read. "The novel came into popular awareness towards the end of the 1700s," says Pen & the Pad, "due to a growing middle class with more leisure time to read and money to buy books." More books were available, and more people had the time to read and the money to buy them. Books were becoming especially popular with women and that was worrying some people.

French literature and language professor Margaret Cohen explained to The New York Times that for nearly a century women were warned away from reading because they "were considered to be in danger of not being able to differentiate between fiction and life." English professor Barbara M. Benedict said that "novel reading for women was associated with inflaming of sexual passions; with liberal, radical ideas; with uppityness; with the attempt to overturn the status quo." The professors described scenes in famous novels of the era, like Madame Bovary, demonstrating the latent misogyny. Cohen points out that even Jane Austen parodied the idea with one character who was a "typical young woman who can't distinguish between fact and fiction."