Britain's Notorious Great Train Robbery Explained

If there's one thing history tells us, it's that people are always gonna steal stuff. Stuff is literally begin stolen all the time—as you read this, someone, somewhere, is being robbed. Most of the time, of course, those thefts are relatively small scale. Even bank robberies are pretty small scale on average: The Washington Post tells us that the average bank robber walks away with just $6,500.

But some robberies rise above the rest either due to the amount stolen, the cleverness of the heist, or both. Sometimes thieves tunnel underground in order to steal millions from a bank vault. Sometimes thieves land a helicopter on the roof of a cash depot and smash through the upper windows. Sometimes thieves strap a bomb onto someone and instruct them to rob a bank for them.

But for sheer audacity, profit, and old-school cool, nothing beats the Great Train Robbery of 1963. Not only did the thieves get away with a huge amount of loot (close to $76 million in today's money), but they did so with one of the best-organized and least-violent robberies of all time, and then made careers out of making law enforcement look bad. If you're unfamiliar with this incredible story, here's Britain's notorious Great Train Robbery explained.

The Great Train Robbery was meticulously planned

As History reminds us, on the evening of August 8, 1963, a special postal train known as The Up Special left Glasgow hauling an unusually large amount of cash due to a bank holiday in Scotland. Just past three in the morning, the train was stopped, a gang of 15 thieves boarded and stole a cool £2.6 million in small bills.

As detailed by How Stuff Works, the robbery was incredibly well-planned. After being tipped off that the postal train hauled huge amounts of cash on a regular basis, a career thief named Bruce Reynolds put together a team in a real-life Ocean's 11 scenario. He started with the legendary Gordon Goody, a thief and part-time hairdresser, and between the two ringleaders they assembled a team of 15 men.

Next, they learned how the signals worked on the tracks the train ran on, figuring out how to disable them and then hook them up to their own batteries so they could signal the train to stop in an isolated area. According to Smithsonian Magazine, the thieves knew which of the train cars had been outfitted with alarms and which hadn't. They were so well prepared the entire heist took just 15 minutes. By the time a conductor went forward from the rear of the train to investigate the delays, the thieves were long gone.

None of the thieves carried weapons

When we think of heists involving millions of dollars or pounds, we tend to imagine guns. Lots and lots of guns. It's been ingrained into us with every Hollywood movie—when thieves get together to rob some place, they usually come armed to the teeth and prepared to kill anyone who gets in their way. But the men who perpetrated one of the biggest thefts in history didn't have a single gun with them. In fact, they didn't even carry any weapons. And only one person was injured during the Great Train Robbery.

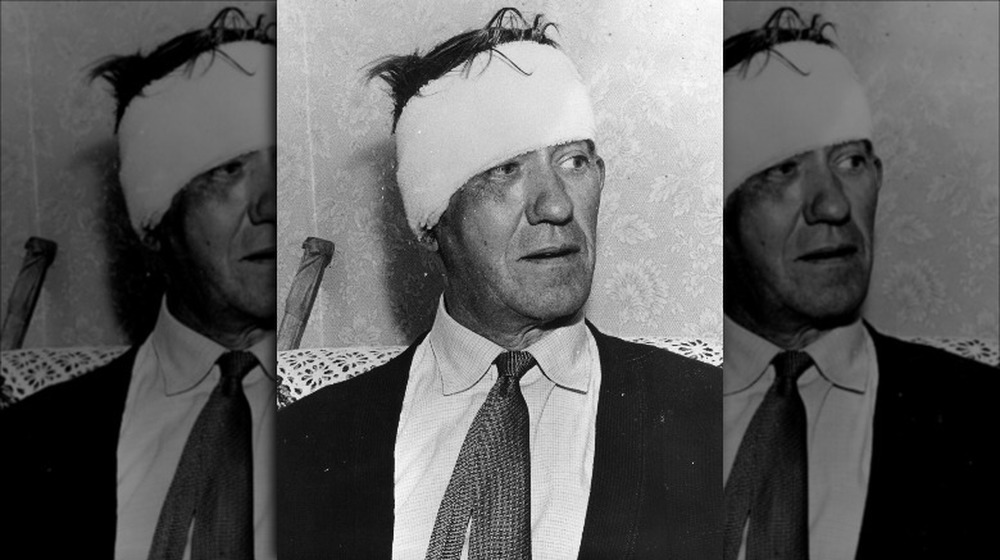

As noted by BBC On This Day, there were about 75 postal workers on the train working to sort the mail being transported, but most of them were completely unaware of the robbery taking place. The Encyclopedia Britannica details how the thieves managed to avoid violence for the most part: When the train stopped unexpectedly because the thieves had tampered with the track signals, the fireman went forward to investigate and was immediately captured. The engineer, Jack Mills, arrived on the scene and in a scuffle was hit on the head pretty hard. The thieves then broke into the car carrying the money and managed to restrain the four men inside without incident.

Thanks to careful planning and discipline, the men managed to steal millions in cash with just one incident of violence—and no weapons of any kind.

They hid at a farm—and left behind evidence

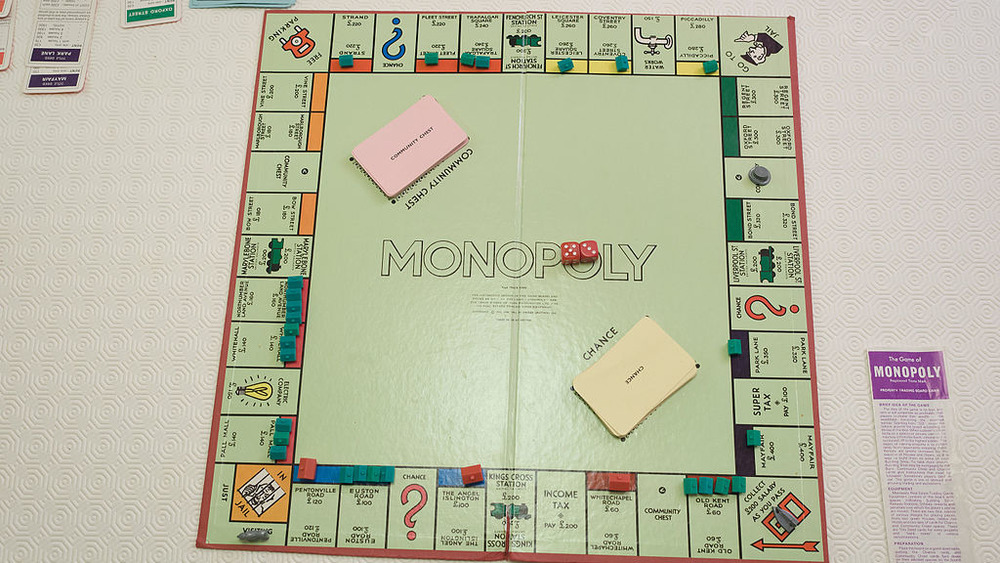

The perfect planning and cool-headed execution of the plan began to unravel once the gang had escaped with the money from the Great Train Robbery. They traveled to Leatherslade Farm in Buckinghamshire and laid low for a few days, hiding their vehicles under cover. They stocked the kitchen with food and played board games to pass the time, and started to bury some of the evidence. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica they hired six men to burn the whole place down when they left in order to destroy evidence.

But locals noticed all the activity at the farm and contacted the police. As noted by Atlas Obscura, the gang had to clear out immediately, so the place couldn't be burned, and they didn't even finish burying the postal bags that had contained the money. Worse, they left behind tons of evidence, including fingerprints on Monopoly game pieces (they played with real money) and the vehicles they'd used in the robbery. As a direct result of the rushed escape, the police were quickly able to identify every single one of the thieves and launch a nationwide manhunt that saw 12 of the 15 arrested within weeks.

The money from the Great Train Robbery was never recovered

The 1963 train heist known as the Great Train Robbery was a sensation in part because of the slick, well-planned nature of the heist itself—but also because of the huge amount of money stolen. The thieves got away with £2.6 million, which would have been more than $7 million at the time, and more than $75 million in today's money.

To give you some idea of how much work that was, History tells us that the cash—which was in small bills—was transported from the train to the local farm the thieves used as a hideout in 120 mail bags. That amount of cash is pretty heavy and pretty difficult to hide.

And yet, despite the fact that every one of the criminal gang was eventually arrested and imprisoned for their crime, Smithsonian Magazine tells us that the authorities only recovered about 10 percent of the cash. Millions of pounds just vanished and were never traced in any way. Several of the criminals evaded capture by the police for several years and almost certainly used their stolen money to pay their bills, but the police never managed an accounting.

One of the robbers was a fugitive for decades

If you're going to be involved in one of the most sensational crimes of all time, you'd better be prepared to deal with the consequences. Ronnie Biggs, part of the gang that pulled off the Great Train Robbery, certainly was.

As reported by History, Biggs was arrested for his role in the heist and sent to prison with a sentence of 30 years. But after serving just 15 months of his sentence, Biggs and several other prisoners climbed over a prison wall while outside exercising, were picked up by a truck, and vanished. As noted by NPR, Biggs had plastic surgery to throw authorities off his scent, then moved to Rio de Janeiro. Biggs lived the high life, and wasn't shy about telling people who he was—he even sold T-shirts to tourists commemorating his role in the caper.

Biggs remained in Brazil for 36 years, finally returning to England after a series of strokes left him in poor health. He was sent back to prison, but as reported by The New York Times he was released due to his deteriorating health in 2009. According to The Independent he told the parole board that he regretted his crimes, and that his life had "been wasted."

Several of the robbers evaded justice for years

By all accounts, Bruce Reynolds was the leader of the gang that managed the Great Train Robbery. A life-long thief and antiques dealer, Reynolds—whose nickname was "Napoleon"—was the one who first took the information about the money on the postal train to the local criminals who began recruiting the team.

When the authorities identified the thieves and began chasing them down, Reynolds was also the best prepared. According to BBC News, he had a fake passport at the ready and immediately fled with his family to Mexico. From there, they moved to Canada under assumed names and lived quietly for five years. It was only when Reynolds returned to England in 1968 that he was finally arrested.

Similarly, according to ITV News, Buster Edwards—a former boxer and club owner—fled to Mexico when the police came for him, and remained there for three years in relative comfort. When the money ran out and his family expressed a desire to go home, he returned and gave himself up in 1966, eventually serving nine years in prison before being released. A film starring singer Phil Collins about Edwards' life was released in 1988, called Buster.

The thieves lied to get a book deal

One of the most incredible aspects of the Great Train Robbery is how this incredible crime became mired in myth almost immediately. And much of the myth that built up around the heist was provided by the robbers themselves—as The Spectator notes, gang leader Bruce Reynolds admitted later in his life he had trouble remembering what was true and what had been invented.

What's really amazing is that anyone trusted these thieves. Reynolds and the rest of the crew were career criminals who were obviously not above lying for profit—something author Piers Paul Read discovered in 1978 when his publisher negotiated a large advance with several of the thieves for a book called The Train Robbers. As the Guardian reports, the publisher wanted assurances of revelations to drive books sales. In order to justify the advance, Reynolds and his compatriots told Read that Otto Skorzeny, notorious Nazi and reputed leader of Odessa, a group of high-ranking Nazis who supposedly escaped Germany at the end of World War II, had been the robbers' financial backer.

That sensational claim landed the book deal, but it was completely invented. When Read found out, he added a final chapter to the book describing his confrontation with the robbers over the lie, turning the deception into an advantage.

An innocent man may have died in jail

While the actual robbery of the postal train was conducted with near-perfect precision, a 15-minute operation that left nothing but confusion in its wake, the aftermath was anything but. As noted by the Encyclopedia Britannica, the thieves left all kinds of evidence behind when they fled the farm they were hiding at, and a wave of arrests soon followed.

One of the men arrested was Bill Boal. As BBC News reports, Boal was a known associate of one of the men involved in the robbery, Roger Cordrey, and he was found in possession of £141,000 of the stolen cash. He was duly charged with armed robbery and receiving stolen goods. But as reported by The Guardian, Boal insisted he was innocent and that he'd come to have the money because Cordrey owed him a debt—and The Evening Standard notes that the gang's leader Bruce Reynolds stated that Boal had nothing to do with the heist.

Boal was convicted and sentenced to 24 years, but as historian Jim Morris writes, the court wasn't so sure about the armed robbery charge so it substituted a 14-year sentence for the stolen goods charge. Sadly, Boal died of cancer while still in prison, protesting his innocence to the end.

The robbers became celebrities

When a gang of criminals steal a huge amount of money in a daring heist, you might assume the general public would want them caught, charged, and imprisoned as quickly as possible. But one of the most remarkable aspects of the Great Train Robbery is how positive the public's reaction to the crime was.

As noted by Smithsonian Magazine, an early sign of the public's reaction could be seen in how The New York Times reported on the incident, calling it a "British Western" and comparing the thieves to the criminal feats of Jesse James. When the thieves were rounded up, the authorities imposed extremely harsh sentences of 30 years each, despite the lack of violence used in the robbery. The public was shocked at the sentences. According to The Guardian, author Graham Greene wrote that he had "admiration for the skill and courage behind the Great Train Robbery" and was "shocked by the savagery of the sentences."

One reason for this mild reaction was the mood of the British public at the time. As the Irish Independent explains, the government had just suffered through a devastating sex scandal that had forced the prime minister to resign in disgrace, and the country as a whole was enduring an extended economic crisis in the wake of World War II and the erosion of England's imperial power. Many saw the Great Train Robbery as a blow against a corrupt state as opposed to a crime of greed.

The inside man of the Great Train Robbery remained unidentified for decades

The efficiency and near-scientific planning of the Great Train Robbery—a huge, complicated heist that took just 15 minutes—could not have been pulled off without a lot of inside information. As reported by Smithsonian Magazine, from the very beginning of the investigation the police knew that a postal worker known only as "The Ulsterman" had met with robber Gordon Goody, giving the thief details on the train's operation, the track signals and how they worked, and even the status of a new alarm system being installed on the train cars.

Only three of the thieves knew the identity of The Ulsterman, who received a cut of the stolen money in exchange for his assistance. Remarkably, none of them revealed his identity for more than 50 years, keeping a promise they considered a solemn vow. As reported by The Guardian, Gordon Goody revealed The Ulsterman to be postal worker Patrick McKenna in 2014. Goody stated he was only willing to do so because he assumed McKenna was dead.

Strangely, McKenna never seems to have spent the money, and never spoke of his involvement in the robbery. His family suspects he gave the money away, or that other thieves, aware of his involvement, stole it from him.

The London underground formed an escape committee

Although the authorities identified most of the thieves involved in the Great Train Robbery within a few weeks of the crime—largely due to fingerprints left behind at the farm they used as a hiding place immediately after the heist—rounding up the gang was more of a challenge. Several gang members managed to flee the country and remained fugitives for several years. And even the thieves that were arrested and put in jail proved to be slippery.

According to BBC One, Charlie Wilson became known as "The Silent Man" during his trial due to his habit of not commenting on any of the proceedings. A childhood friend of gang leader Bruce Reynolds, Wilson was convicted of armed robbery and sentenced to 30 years in prison. But as Smithsonian Magazine reports, Wilson's friends in the London criminal underground didn't think this was very fair, and formed a literal Escape Committee to plot breaking him out of jail. Incredibly, the authorities were aware of this and considered Wilson a security risk as a result—and yet on August 12, 1964, after just four months in prison, Wilson was in fact broken out.

As History notes, several men literally broke into the prison where Wilson was being held and brought him out. Wilson fled to Canada, where he lived as a fugitive for four years before being apprehended and brought back to England to finish out his sentence.

The loot from the Great Train Robbery became worthless

One of the greatest ironies of the Great Train Robbery is that after all the planning, all the work, and then all the years spent fleeing justice or serving prison terms, the money stolen became worthless after just a few years. In 1963 when the robbery was committed, the United Kingdom still used a currency system that dated back centuries. As BBC News explains, under that system there were 12 pennies to the shilling and 20 shillings to the pound, and the currency included obsolete denominations like the florin and the half crown. This system actually ultimately dates back to Roman times, and was based on a pound of silver being divided into 240 pence.

By the late 1960s, this system was showing strain in the modern world, and the decision was made to "go decimal." Decimal Day was set as February 15, 1971—as of that day, every pound would be made up of 100 pence. A few years before, the country began introducing 5, 10, and 50 pence coins to prepare everyone.

As Smithsonian Magazine notes, one side effect of Decimal Day rendered all the cash notes stolen by the Great Train Robbers instantly worthless, as they were no longer considered legal tender.