The Untold Truth About The First Westerns

There's been a lot of talk about western films of late. The Film Threat recently opined that although the popularity of the genre has faded, "the time could be ripe for westerns." On the opposite side of the pendulum is journalist Michileen Martin, who cites the expense of creating sets, the lack of popularity overseas, and the number of recent flops as just some of the reasons westerns are currently not in the mainstream. Thank goodness for The Vore, which lists several promising westerns like No Man's Land, News of the World, Those Who Wish Me Dead, and First Cow, all of which came out in 2020 or 2021.

Today's top 10 westerns, according to Internet Movie Database, include movies as recent as 2012's Django Unchained and as old as 1925's The Gold Rush starring Charlie Chaplin, with a nod to three Clint Eastwood westerns. And 2015's The Revenant and The Hateful Eight are only a little bit further down the chart. Notably the love for westerns goes back to the late 1800's, the actual beginning of motion pictures, which quite literally took place in the still-alive Wild West. Although the earliest films only lasted a few minutes (it was believed viewers' attention spans were too short for anything longer, says Wired), they paved the way for our love of modern western movies. Read on for the untold truth about how westerns kicked off the world of film as we know it today.

The very first 'movie' was not a movie

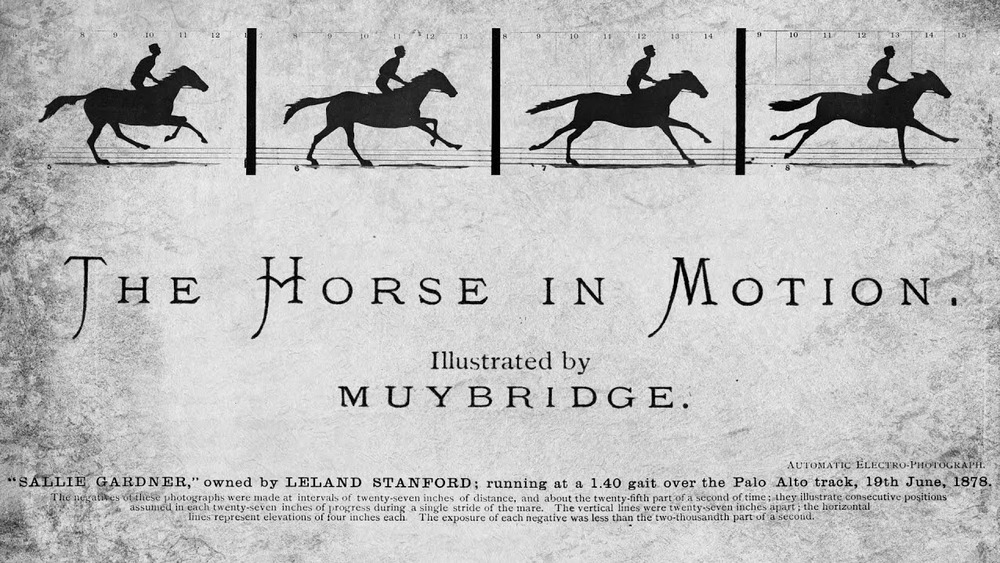

The Online Etymology Dictionary confirms that the word "movie" had yet to enter the English language when Eadweard Muybridge produced the very first moving picture in 1878. Smithsonian explains that the idea actually stemmed from a debate as to whether "all four of a horse's hooves came off the ground when it runs." That's when Leland Stanford, a huge California racehorse fan and entrepreneur, called on Muybridge to see if he could settle the argument in 1872. The somewhat erratic Muybridge might have immediately proven the theory one way or another had he not taken time out to shoot his unfaithful wife's lover to death. Muybridge pleaded insanity, but a jury found the murder was "justifiable homicide" instead.

Set free, Muybridge made his way west to a Palo Alto racetrack in California. After conferring with Stanford, he set up special sets and tripwired cameras to capture images of a horse as it ran around the track. Next, Muybridge created the zoopraxiscope, which Britannica explains was a lantern made to project the images of the horse on a screen with a "rotating glass disc, producing the illusion of moving pictures." The result is today titled today as "The Horse in Motion," and proved that all four of a horse's feet can indeed come off the ground as it runs. An original copy of Muybridge's images remains on file at the Library of Congress.

Thomas Edison built America's first film studio

Today, debates rage over who was responsible for inventing electricity: inventor Nikola Tesla, who came up with alternating-current (AC), or his former boss Thomas Edison, who invented direct-current (DC). What is known for sure, says the Library of Congress, is that in 1888 Edison and his assistant, William Dickson, created two unique inventions: the Kinetograph, a special camera that could capture motion on film, and the Kinetoscope, a "a peep-hole motion picture viewer." Edison and Dickson's first film test, according to Open Culture, was filmed in 1890 and showed Dickson simply moving around. Understandably, this first trial—titled Monkeyshines—was very blurry and only spanned mere seconds.

Although Monkeyshines was indeed primitive, Edison was infatuated with his brainchild. Within a short time he had built his own studio, the Black Maria, in New Jersey. ShiHi touts the Black Maria as being "the world's first film studio," even though it was not meant for productions for the big screen we know today—that hadn't been invented yet. By 1891, Edison and Dickson had fine-tuned their ability to film live motion, producing a seconds-long film of Dickson waving his hat. This too was just a test, says the Library of Congress, but it was much better; this time, Dickson could clearly be seen "greeting" the camera. In 2015, Christopher David Heinmiller restored and colorized the clip for a better view.

The birth of the Western film

The first actual western movie, per se, was produced at Edison's Black Maria studio in 1894. But there was no story, no plot, and no characters save for a real live cowboy. Remember, there was no such thing as Hollywood just yet. There were, however, lively and popular wild west shows like Buffalo Bill's Wild West, which Center of the West says first premiered in 1893. Buffalo Bill Cody's show caught Edison's attention, and in 1894 he invited the showman to bring some of his acts to the Black Maria. Edison recorded three of them in all. One of them was Bucking Broncho, described as "a fine exhibition of horsemanship" by cowboy Lee Martin as he stayed atop a wild bronco. Another was Sioux Ghost Dance, and featured real Natives performing a sacred dance.

The most popular of the three films today is footage of sharpshooter Annie Oakley as she shot targets on a board and coins thrown in the air by her husband. According to the Library of Congress, the footage was actually captured in 1895. Like the film of Dickson and his hat, Oakley's 15 seconds of fame was remastered, colorized, and sound added by Rossov Remastering in 2020. Oakley would appear in more short clips, including an undated film reel as she shot an apple from her dog's head, and her last shooting exhibition, which Center of the West has posted on their Facebook page.

The longest Western: The Corbett-Fitzsimmons fight

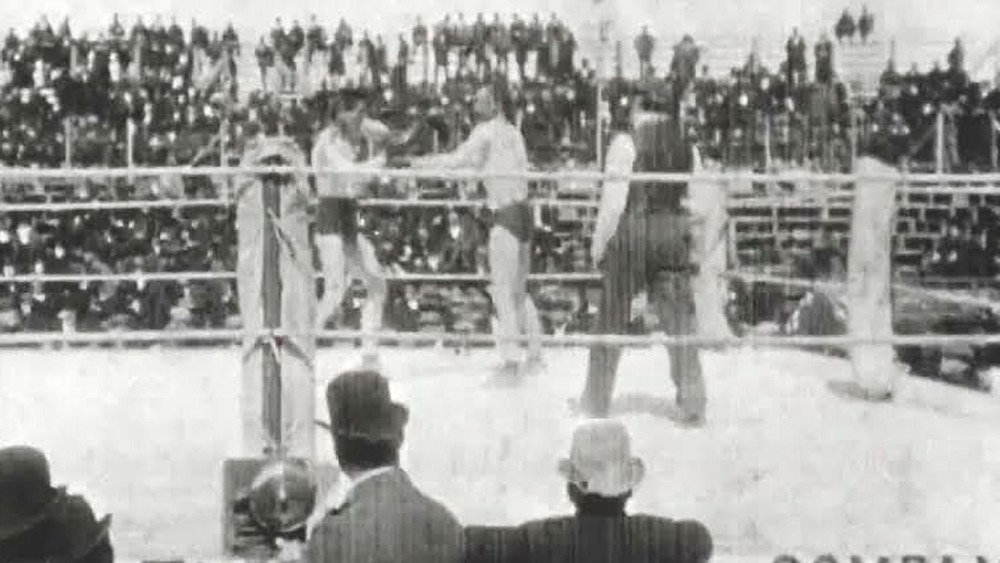

The first "western" actually filmed out west was a boxing match between James J. Corbett and Bob Fitzsimmons at Carson City, Nevada on St. Patrick's Day in 1897. Variety says the fight, and others like it, were the "leading factor in establishing the commercial success of movies." The original film, according to the Library of Congress, ran over 90 minutes, making it the "first feature-length film." This time, boxing promoter and early cinematographer Enoch Rector was the man behind the camera. Rector had previously filmed other fights at Thomas Edison's Black Maria studio, says Bright Lights Film. He might have done more there if not for Edison's objection to filming more fights.

According to Barak Y. Orbach, Edison publicly denounced filming prizefights after boxer Andy Bowen died from his injuries the day after fighting George "Kid" Lavigne in 1894. Undaunted however, Rector worked for three more years on his own Veriscope, a gigantic camera inside a "wooden shack" which had to be operated simultaneously by three men in order to capture all the action. Rector gave his film a more genteel name, the "Corbett-Fitzsimmons Carson City Sparring Contest," when he advertised its premiere in New York on May 22, 1897. The audience loved it, "roaring out at the screen as if they were actually seated at ringside." Both Fitzsimmons and Rector won the fight: Fitzsimmons with his fists and Rector with his film, which earned nearly a million dollars in ticket sales.

Edison captures daily life in the West

Once Thomas Edison publicly refused to film anymore boxing matches, he began focusing on other interesting subjects instead. Between 1894 and 1897, he recorded a series of short films, from the silly The Boxing Cats and a Chinese Laundry Scene to serious with The Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots. The latter was a realistic portrayal of the queen's beheading, using a dummy on the chopping block. Public Domain Review says it was one of "the first films to use trained actors," although "Mary" was portrayed by Robert Thomae of the Kinetoscope Company.

Edison also wanted to focus on daily life in the real west with real people, including the inauguration of President William McKinley in 1897 and Theodore Roosevelt's Rough Riders in 1898. But he also sent his employees, James White and Frederick Blechynden, out west on various railroads—who were glad to partly finance the excursions for their promotional value. The pair recorded scenes in California and Colorado, as well as footage of men buying supplies in Seattle, Washington before setting out for the Gold Rush in Alaska and the Klondike. All told, at least 51 clips were recorded as the men traveled around through 1898, including their return to the east where they filmed a new recruit from the 1st Ohio Volunteers in Florida being tossed around on a blanket. Notable too is that the short films captured American military troops during the 1898 the Spanish-American War.

The first Western to actually tell a story

In 1899, Edison took his first stab at actually telling a story on film. In February, according to Internet Movie Database, he released a 20-second clip titled Poker at Dawson City, which mostly portrayed card players spilling drinks on themselves after some sort of tousle at the poker table. But it was Cripple Creek Bar-Room, released in May, that The Silent Western and other film aficionados agree was the first real western. Why did Edison choose to focus on Dawson City and Cripple Creek? Because both places were the scene of late 19th-century gold booms.

Cripple Creek, Colorado was especially notable because in its time, it was the site of the last great gold rush in the state. In fact, the gold boom is believed to have generated at least 30 millionaires, according to the Mining History Association. By the turn of 1900, the Cripple Creek mining district was known all over America and beyond. Although Cripple Creek Bar-Room lasted only 48 seconds, the film ably portrayed a drunk man who wanders into a bar and disrupts the other customers, resulting in a scuffle. He then gets ejected by the burly barmaid (played by a man), who buys the house a round. Although director James H. White oversaw filming from the Black Maria studio in New Jersey rather than Colorado, Edison perhaps surmised that people would watch the short because it depicted world-famous Cripple Creek, the "World's Greatest Gold Camp."

The Great Train Robbery was the first feature film

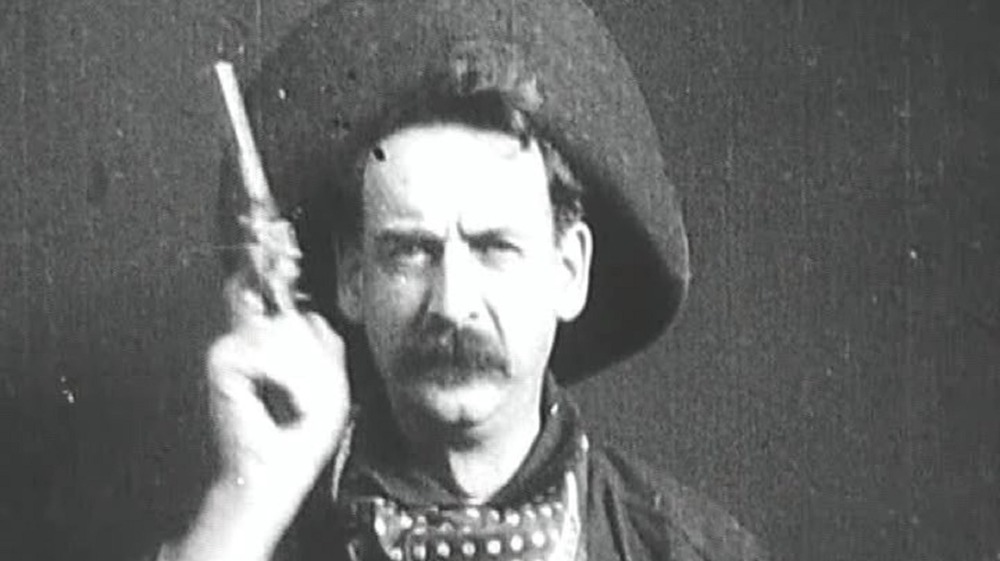

Thomas Edison's film success took another gigantic leap in 1903 when he produced The Great Train Robbery. Edwin S. Porter directed the movie, which the Metropolitan Museum describes as "one of the first westerns to tell a unified story with a dramatic climax." As one might guess, the story centers on a group of outlaws who burst into a train station, rob it, and climb aboard the incoming train. One employee is violently beaten and thrown off the train before the passengers are held up. The gang escapes with the posse in hot pursuit but are eventually caught. The film ends with one of the outlaws dramatically firing his gun right at the screen.

Although The Great Train Robbery was only eleven minutes long, the New York Times submits it actually "set the standard" for westerns of the future. Today, according to Film Site, historians may be interested to know the film was inspired by a robbery by outlaw Butch Cassidy and his gang at Wilcox, Wyoming in 1899. The film also generated America's "first cowboy star," Gilbert "Broncho Billy" Anderson, who portrayed three different characters. And the movie was so popular that director Siegmund Lubin produced another film with the exact same title in 1904. In Lubin's version, when the outlaw fired his gun at the screen in the end it was so realistic that people in the audience screamed and plugged their ears—even though there was no sound.

The rise of competitors in film making

Siegmund Lubin's virtual plagiarism of The Great Train Robbery signified the growing popularity of film making. Edison didn't like it one bit; according to writer Brian Manley, the inventor tried to quell his competition, but to no avail. One of his biggest competitors was William Selig, founder of the Selig Polyscope Company in Chicago. Later, Selig would be the first producer to move his studio to the West Coast and notably, he produced an amazing 2,492 films and shorts between 1896 and 1938, according to Internet Movie Database. One of Selig's most controversial projects was Tracked by Bloodhounds, or a Lynching at Cripple Creek in 1904.

Tracked by Bloodhounds was notable for many reasons. It was the first western to be filmed on location, in Cripple Creek, Colorado. SMU Libraries says that also, the actor playing the tramp who is hanged after he murders a woman was played "by a light-skinned African American, who was nearly lynched by other Cripple Creek Blacks" because they feared violence against themselves. Added to the furor was that the Cripple Creek District was right in the midst of a most violent labor war. Certain newspapers led potential audiences to believe the movie was actually about the dirty deeds of a striking miner. Still, the movie remained popular, playing in Telluride theaters as late as July, 1905.

Colorado became a leading film backdrop

William Selig liked Colorado enough to keep an agent, H.H. Buckwalter, making films there according to journalist Rob Carrigan. So did Edison. But Colorado, with it's high elevations and harsh winters, was not always a convenient location for filming: Following Selig's lead, another western debuted in 1906 from Colorado, titled From Leadville to Aspen: A Hold Up in the Rockies. This movie, however, was filmed entirely in the Catskill Mountains of New York. The film, shot entirely with a view of the front of a train car, consisted of robbers busting in, robbing everyone, and killing a train employee according to Internet Movie Database. And it was viewed by audiences in the most unique way.

World Catalogue explains that the film's producer, American Mutoscope and Biograph Co., shot the film for use by a company called Hale's Tours and Scenes of the World. The company was worldwide, their "theaters" being specially built sets (like a train car in this case). Viewers entered the car, sat in a real train seat, and viewed a screen at the front. As they watched the film, sound engineers produced the noise of a train car on the tracks as the "theater car" rocked back and forth to simulate travel. It was really the earliest version of virtual reality gadgets like Oculus. Meanwhile, film makers would continue to call Colorado home. To date, at least 4,410 movies have been shot in Colorado.

The birth of the Western movie star

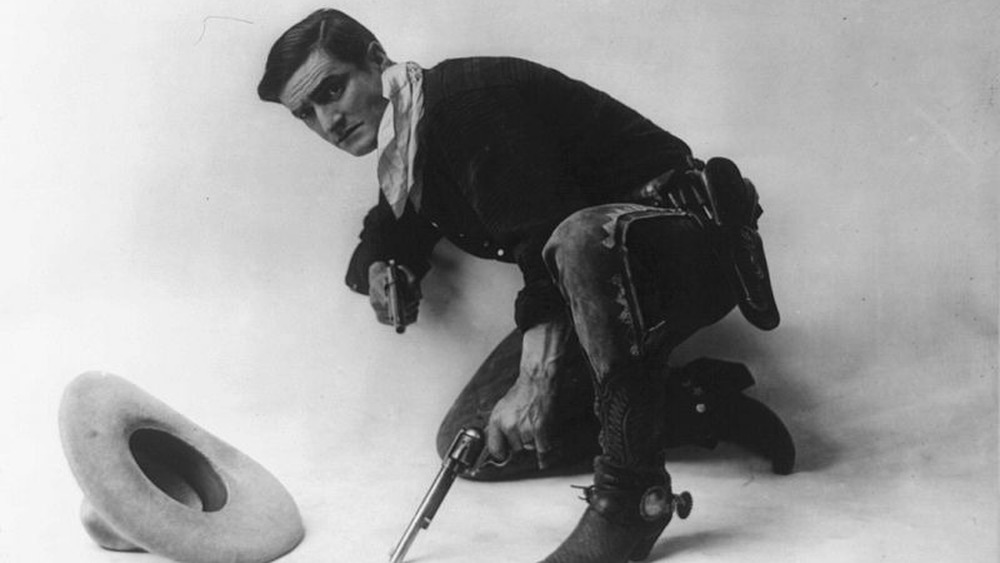

History of Film submits that between 1895 and 1906 silent movies, as they were then known, "created foundation for future establishment of movie studios, worldwide known stars, and early film grammar." The movie industry was taking a firm grasp in the world of entertainment as the stories became more sophisticated. Take The Cowboy Millionaire in 1909 for instance, which starred Tom Mix and according to blogger Klaus Kreimeier was so successful that it was remade in 1913. Mix and other actors — like Gilbert M. "Broncho Billy" Anderson and William S. Hart — were fast gaining fame and fortune, says Cowboys and Indians.

More stars would come as silent movies charged into the nineteen-teens; the Los Angeles Times lists such notables as Clara Bow, Charlie Chaplin, Greta Garbo, Buster Keaton, Mary Pickford and more who became household names. And with the opening of the Nestor Film Company which signified the official birth of Hollywood in 1911, cinema as we know and love it came into its own. And at the top of the list of western actors, Tom Mix would remain among the most popular as he transitioned into the "talkies" era with 282 movie credits. Mix died in a tragic car accident in 1940 shortly after his last movie, a short called Rodeo Dough, came out in theaters.

Hollywood's first Western 'talkie'

Movie history buffs know that in 1927 film took a giant leap forward with The Jazz Singer, the first feature film to provide sound. Internet Movie Database confirms the movie was given an honorary award at the Oscars for being "the pioneer outstanding talking picture." The following year America's first western "talkie," In Old Arizona, premiered. The movie also was the first talkie to be filmed outdoors, on location—but in Grafton, Utah instead of Arizona, according to Cinestaan. Based The Caballero's Way, a short story by O. Henry, In Old Arizona tells the story of the Cisco Kid whose girlfriend does him wrong as he is pursued by the sheriff.

Walsh was most excited to film the movie outdoors telling the producer, Fox Studios, "We'll knock the public dead." Unfortunately, Walsh had shot a few scenes and was on his way back from Utah when he was in a bad car accident, losing his eye but also his job and even his starring role as the Cisco Kid as he recuperated. Cummings took over, and the lead role was given to actor Warner Baxter, a veteran of silent films. Baxter won the second-ever Oscar for best actor, and went on to make numerous films before he died in 1951. In Old Arizona remains so popular that one must buy it to watch it even today, although clips of it can be viewed on various websites.