The Untold Truth About The Origins Of Steampunk

Imagine for a second, if you will, the modern era, with all its technological advancements, except minus the circuitry, electric machinery, and digital communication. Instead of a touchpad you've got an analog mechanism of dials, knobs, and gears. Instead of an airplane you've got a steam-powered zeppelin taking port at the tip of a multi-story, ornately furbished clockwork tower and transportation hub. Instead of a cybernetic replacement for a lost limb, you've got an arm of brass contraptions, leather straps, and gleaming chrome. Such is the vision of "steampunk," literary cousin to cyberpunk and now an entire universe of art, design, leatherwork and metalwork, literature, video games, cosplay and in-person events, and more.

The definition of "steampunk" is itself elusive. Sometimes called "neo-Victorian futurism," the Ministry of Peculiar Occurrences put it best: "Steampunk is modern technology — iPads, computers, robotics, air travel — powered by steam and set in the 1800s." So remove from your mind cyberpunk-and-anime-influenced sci-fi like The Matrix, Ghost in the Machine, Black Mirror, Ex Machina, or the Deus Ex game series. Excise all visions of a dystopian future fixated on urban crush, neon glow, cryptology, incessant surveillance, brutal corporations, evil AI, and mad cyborgs. Imagine that history took an alternative turn at the zenith of the Industrial Revolution, where the aesthetics of the past, both real and romanticized, merge with the technological grasp of the present.

Steampunk has had flare-ups, and quiescence, over the years. But where did it come from, exactly?

Inspired by Victorian era's technological surge and aesthetic

It's a strange, uncanny, and very culturally "meta" journey from the soot-laden, chemically toxic, technological and economic revolution of the Victorian era (1837-1901) to arrive at something like Bjorn Hurri's steampunk takes on Star Wars characters on Concept Art World, or the whale-fat-based, not fossil-fuel-based, revolution in stealth games like 2012's Dishonored (shown on YouTube), or the prestige costume market of hand-crafted, limited steampunk accessories on Etsy.

Steampunk, as an artistic genre and aesthetic take, is centered on Victorian England, named after history's illustrious Queen Victoria, an era which gave us Dickensian poverty, Wildean outlandishness, the Great Stink of 1858, and people nibbling on arsenic wafers to maintain their complexion (per The Quack Doctor). As Steampunk Avenue tells us, steampunk also takes influence from the Belle Epoque era in France (1871-1914), a time of relative calm and prosperity between the bloody Franco-Prussian War (1870), the radical government of the Paris Commune (1871), and World War I (1914-1918), as well as Old West United States (early 1800s-1895), including the Edison-Tesla-Westinghouse technological War of the Currents in the late 1880s through early 1890s.

Mash all those things together, and add some colorful and adventurous fictionalization, more than a dollop of retrospective historical rose-tinting, a huge heap of creative anachronisms, and definitely less lethal personal hygiene routines. In the end, you arrive at the inspiration for, and interpretation of, an entire sub-genre of what is, essentially, science fiction.

Sci-fi progenitors at the turn of the 20th century

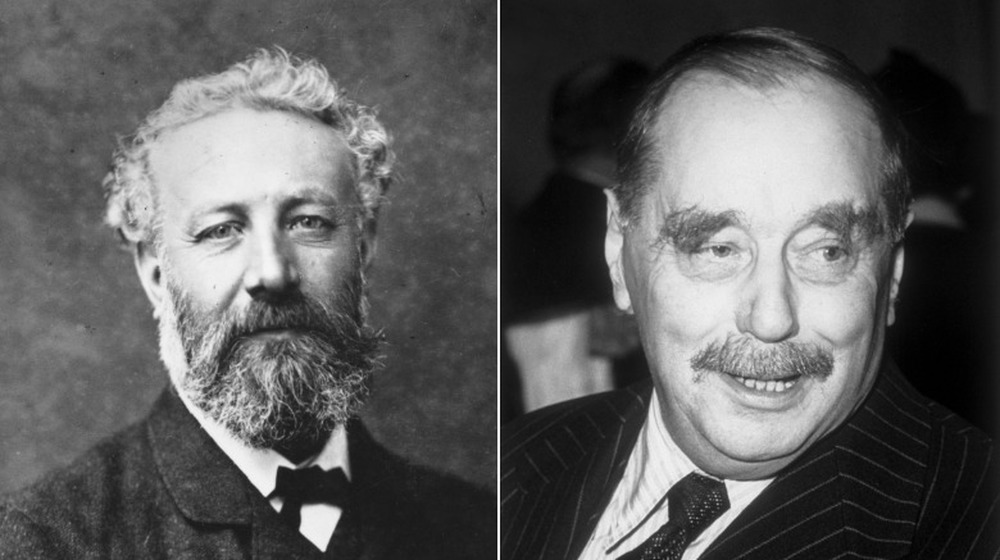

Steampunk, fundamentally, can be described as a sub-genre of science fiction. Its roots are literary in nature, and, as Big Bead Little Bead says, can be traced back to the fantastical tales of sci-fi's earliest grandfathers, H.G. Wells (1895's The Time Machine, 1898's War of the Worlds) and Jules Verne (1867's Journey to the Centre of the Earth, 1870's Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea). Both men went through phases of optimism about humanity's future and sociocultural progress at the hands of technology, followed by doomsaying about the dangers of placing technological advancements in the hands of a foolish, infantile humanity.

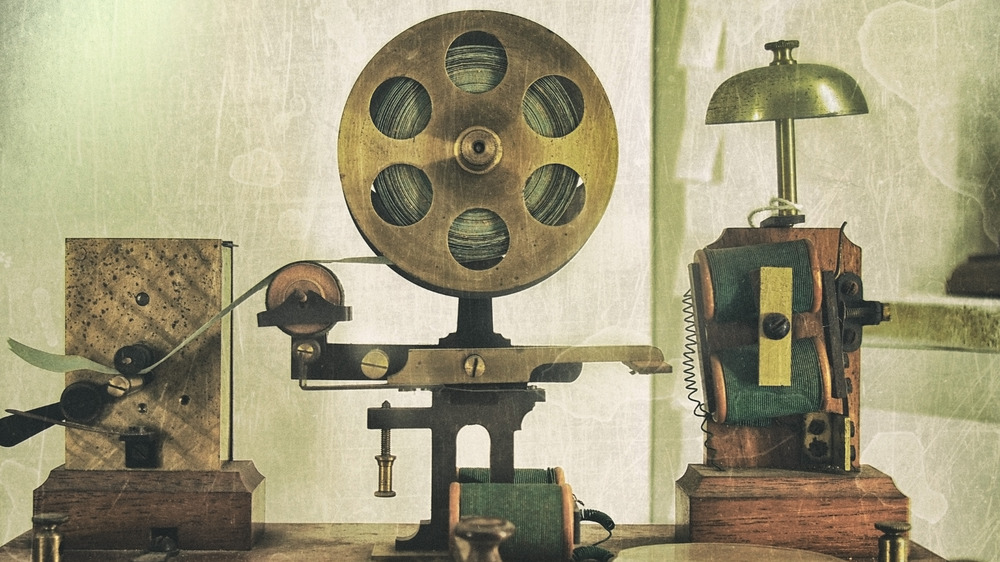

We are now far enough in time from the technology envisioned by those early sci-fi writers to be able to look back and think a) how quaint (or if you're feeling derisive, nonsensical) and b) how charming and creative, even "vintage" or "hipster" (a perspective that colors steampunk's overall vibe). Take Wells' description of the time machine from The Time Machine (readable on Project Gutenberg): "[A] glittering metallic framework, scarcely larger than a small clock, and very delicately made. There was ivory in it, and some transparent crystalline substance."

Kind of cool? Vague enough to work? Sure. And able to inspire the imagination. As soon as these books were translated into films, like 1954's Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, the visual language for steampunk's eventual retro-tech emerged. The landmark film Metropolis (1927), though, arguably made the biggest impact.

The rise of cyberpunk's dystopian futurism

By the time the 1960s rolled around, sci-fi writers such as Philip K. Dick carried into the literary world a reflection of the anxiety, malaise, and growing sense of disconnection and dehumanization felt by a rapidly modernizing world, as Steel Series tells us. He and others carried on Wells' and Verne's tradition of using sci-fi as a tool of social critique, and imbued their work with more than a bit of rambling psychedelia and countercultural drug use. As Grunge says, "[C]omputers, automation, and weapons of mass destruction were a perfect fit with these underground concepts, leading to an increasing presence of dystopian futures in the genre, futures where technology, drug culture, and loss of humanity figured prominently."

In 1984, author William Gibson unified all of these elements with his seminal novel Neuromancer, per the New Yorker, the influence of which cannot be overstated. He coined the term "cyberspace," and brought to us the now-familiar dingy underbelly of tech-laden, neon-flooded cities of economic oppression and violence that, along with films like 1982's Blade Runner, would influence popular culture and visions of the future from then out. 1988's Akira, tabletop RPGs like 1989's Shadowrun, The Matrix Trilogy, the city of Coruscant from the Star Wars prequels, all the way to CD Projekt Red's recent 2020 Cyberpunk 2077: this is cyberpunk in a nutshell.

And funny enough, it's the rise of cyberpunk that spawned steampunk as its own sub-genre, in turn.

The brass-and-steam retro sci-fi offshoot

Steampunk was born, basically, with a single letter written in 1987 by author K.W. Jeter to sci-fi mainstay Locus Magazine about his 1979 novel Morlock Night, written as a sequel to H.G. Well's The Time Machine. The book, which Jeter would later describe as written in a "gonzo-historical manner," involves Wells' underground race of Morlocks from the year 802,701 CE traveling back in time to Victorian England and fighting King Arthur and Merlin (yes, the actual mythological characters). Hence steampunk's whole, subsequent "Victorian" look and feel.

In the letter, readable on Pinterest, Jeter bites on the term "cyberpunk," swapping "cyber" for a more Victorian-themed tech term "steam." In so doing he described himself and fellow writers Tim Powers and James P. Blaylock as "the fantasy triumvirate," or, "steampunks." It wasn't too long before the 1990's "first wave" of steampunk subculture took off from an ultra-small fan base, as the American Historical Association says.

Jeter, whose 1984 debut cyberpunk novel Dr. Adder was described by Philip K. Dick himself as "a masterpiece ... a truly wonderful novel" (per Angry Robot), stated in a 2014 interview — with Lotus Magazine, no less — that he loves going to steampunk conventions and being inspired by younger writers. He says, "[S]ome dismiss it as just people running around with goggles on their top hats and corsets on the outside of their dresses. But it's also this anarchic approach to history. In steampunk, historical accuracy doesn't matter."

A universe of design, fashion, crafts, literature, and events

And now? In addition to Etsy, there's a host of steampunk costumes available. People such as Jake Von Slatt build steampunk-themed computers, as seen on the Steampunk Workshop. The History of Science Museum in Oxford, England held a steampunk exhibit from 2009 to 2010. The Oxnard Steampunk Fest is hosted in California ever year. Oamaru, New Zealand, the "capital of steampunk," broke the Guinness World Record in 2016 for drawing the largest gathering of steampunk fans in the world, per the Guardian.

Steampunk is not without its detractors, including cyberpunk maestro William Gibson, who said (quoted by Medium), "Steampunk strikes me as the least angry quasi-bohemian manifestation I've ever seen." Its recent rise to fame has been seen as a blip by others, or evidence of its death. Rob Beschizza, editor at fringe culture magazine Boing Boing, said, "The specificity of its look — it was often kitsch and self-referential — limited steampunk's appeal to people with less esoteric interests." The advent of the iPhone in 2006, and easy picture sharing, led to its spread, as Medium states, and also removed its mystique. After all, even Justin Bieber did a 2011 steampunk-themed video of "Santa Claus is Coming to Town" (posted on YouTube).

Such sour-faced naysaying constitutes the minority, though. For the rest of us, there's still an entire universe of steampunk still left to not only explore, but invent, just like a novel steam-powered doodad.