Kidnapping, Murder, Unrest: Quebec's 1970 October Crisis Explained

In the 1960s, members of the Québécois separatist movement started a bombing campaign against the Canadian government. In 1970, this standoff escalated to a hostage situation. Overnight, people in Québec found themselves essentially living under martial law.

The October Crisis gripped the nation as a British diplomat and Québec's Minister of Labour and Immigration were kidnapped and held by the Front de libération du Québec. In response, soldiers and tanks rolled through the streets of Montreal while helicopters flew overhead.

Thousands of homes were raided by the authorities and hundreds were arrested, but these actions did little to impede the crisis. Despite being called the October Crisis, the hostage situation lasted until November, and it wasn't until the end of December that most of the kidnappers were apprehended. And in the end, although all of the perpetrators of the hostage crisis were eventually captured, only one of the hostages ended up making it out alive. Kidnapping, murder, unrest: this is Quebec's 1970 October Crisis explained.

The history of Québec's sovereignty movement

Ever since Québec officially joined the Canadian Confederation in 1867, the question of Québec's independence has come up repeatedly. But the modern separatist movement really started to take hold during the 1960s. According to the McCord Museum, the Alliance Laurentienne, which was founded by Raymond Barbeau in 1957, was the first modern organization to push for Québec's independence. Inspired by the writings of Wilfrid Morin, "the Alliance Laurentienne wanted to create a new State, Laurentie, on the shores of the St. Lawrence."

Canada's Human Rights History writes that the independence movement really flourished in the 1960s, with the formation of the Rassemblement pour l'Indépendance Nationale party in 1960s, and the Ralliement National party in 1966. In 1968, several separatist movements were united under Parti Québécois, "capturing seven seats and 23.1 percent of the vote in 1970."

Parti Québécois was founded by René Lévesque, and according to The Canadian Encyclopedia, "was able to rally most of the province's nationalist political groups to its program of political independence coupled with economic association ('sovereignty-association') with English-speaking Canada." However, another separatist group called the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) believed that the political movement of Parti Québécois wasn't radical enough.

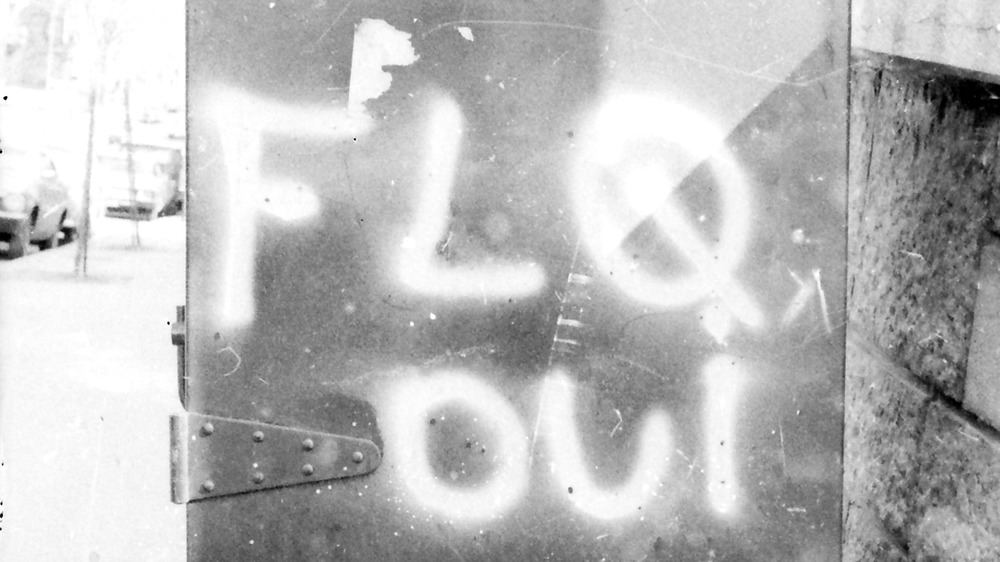

What was the FLQ?

The Front de libération du Québec was founded in 1963 by Raymond Villeneuve, Gabriel Hudon, and Georges Schoetersand, and from the beginning the group became known for their violent attacks. According to "Le Front de Libération du Québec," the FLQ's attacks often incorporated Molotov cocktails or dynamite, and many bombs were left in mailboxes in anglophone neighborhoods, which were "perceived as a symbol of the Canadian government." The Globe and Mail reports that between 1963 and 1970, it's estimated that the FLQ was responsible for placing a bomb "somewhere in Québec every 10 days," with eight people killed and dozens injured over those seven years. One of their bombs, dismantled on July 12th, 1970, contained 150 pounds of dynamite and was one of "the largest bombs ever dismantled in Canada."

There were several factions of the FLQ and they all carried out bombings in one form or another. But according to CBC Archives, the FLQ wasn't the only separatist group to carry out bombings. L'Armée de libération du Québec also participated in the 1963 Montreal bombing spree.

One of the "ideological leaders of the FLQ," Pierre Vallières, described "second-class status of francophones" using "imagery of the Black civil rights movement," describing francophones as the "white n***ers of America." And despite the inappropriate conflation, Vallières' book was one of the first to describe the discrimination that French Canadian Catholics in Québec faced.

James Cross: The first kidnapping

On October 5th, 1970, an FLQ cell known as the Liberation cell led by Jacques Lanctôt kidnapped British diplomat James Richard Cross. According to CBC, four FLQ members took Cross from his home in Montreal. Coincidentally, the day of the kidnapping was also Cross' birthday.

Holding Cross as a hostage, the kidnappers made several demands, including the release of imprisoned FLQ members, "$500,000 in ransom, the re-hiring of the fired truck drivers of the Lapalme company, and a plane to take the kidnappers to either Cuba or Algeria," writes Abidor in "Le Front de Libération du Québec." Otherwise, Cross was to be executed. The FLQ cell also demanded that their manifesto be read on air. The government was given 24 hours to give in to the demands, and although their ultimatum was rejected, the government "indicated that it was ready to negotiate." Initially, the kidnappings were downplayed, and the government agreed to read FLQ's manifesto on Radio-Canada. Part of the FLQ manifesto read: "We will be slaves until Québeckers [sic], all of us, have used every means, including dynamite and guns, to drive out these big bosses of the economy and of politics, who will stoop to any action however base, the better to screw us."

Five days after the kidnapping, Jérome Choquette, Québec's justice minister, announced that if FLQ cell released Cross, they would be able to safely leave Canada, but no other demands would be met.

Pierre Laporte: The second kidnapping of 1970

In response to Jérome Choquette's announcement, another cell of the FLQ kidnapped Pierre Laporte, Québec's Deputy Premier and Minister of Labour and Immigration. The Chénier cell, led by Jacques Rose, took Laporte from his front lawn in Saint-Lambert, reportedly while he was playing football with his nephew.

After the second kidnapping, support for the FLQ among the people was still high. According to "Le Front de Libération du Québec," at least 3,000 people gathered for a pro-FLQ rally on October 15th, five days after the second kidnapping. CBC reports that the second kidnapping gave many the impression "that the FLQ was a large, powerful organization." As a result, the new Québec premier Robert Bourass asked Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau for help. However, the FLQ cells were actually acting independently and "the second kidnapping wasn't planned in advance."

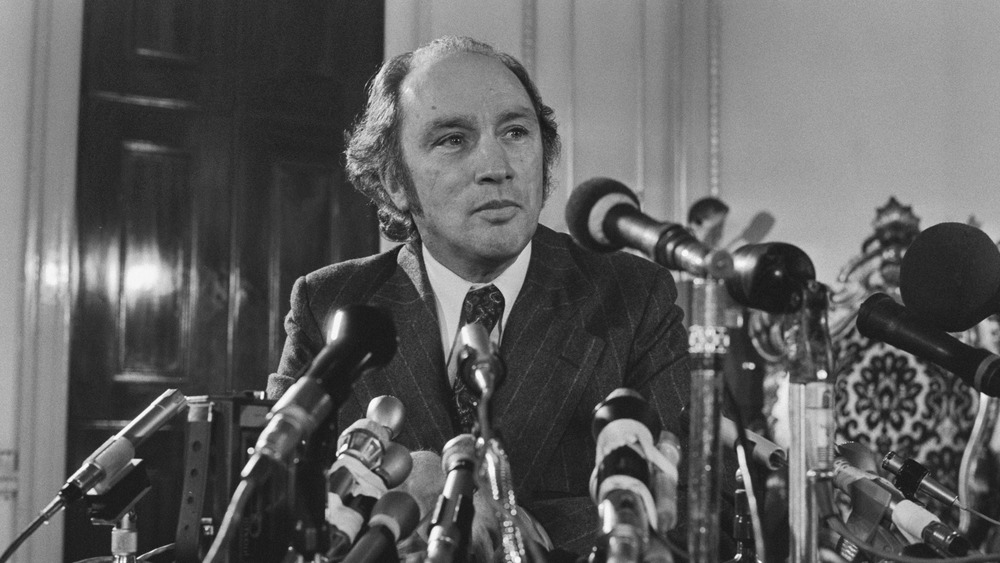

Prime Minister Trudeau sent soldiers "to protect politicians and important buildings" and dismissed any and all concerns regarding the necessity of maintaining "law and order." And when reporters asked Prime Minister Trudeau, "At what cost? How far would you go? To what extent?" Trudeau responded, "Well, just watch me."

Invoking the War Measures Act

And so, everyone watched as soldiers filed into Montreal and Ottawa. Although it was claimed that the soldiers were there to help support the police forces, it was clear that it was "a show of force." And three days later, Prime Minister Trudeau invoked the War Measures Act on October 16th, 1970. According to CBC, this was "the first time in Canadian history the Act was used during peacetime."

The War Measures Act gave police in Canada the power "to arrest and detain people on suspicion alone. The act was created in 1914 [during World War I] for cases of war or national emergency." According to The Globe and Mail, the army, tanks and all, was also deployed "in Ottawa and throughout Québec." But this wasn't just occurring in Québec. Canadians across the country were for all intents and purposes living under martial law and many tried to use it to their own advantage: "The mayor of Vancouver tried to employ the security regulations to clear the city's beaches of hippies."

A poll released on November 15th showed that only five percent of Canadians were "explicitly opposed" to the War Measures Act being invoked and 87 percent approved.

Indiscriminate arrests

Almost 500 people ended up being arrested and held in Québec by noon of October 16th. And according to Legion Magazine, "most [were] ultimately released without charges." 87 percent of those arrested were never charged with any crime.

Officers were also entitled to search any place without a warrant and between 3,000 and 5,000 searches were conducted. Anyone in possession of "'extreme-left' literature, posters, stickers, or pamphlets" was arrested. And police were indiscriminate in their arrests. Even those who supported Québec's independence but were unaffiliated with the FLQ were rounded up. Although police showed a bias against those affiliated with the nationalist cause, they also targeted "the political left in general, including many activists."

And since FLQ was retroactively made a terrorist organization, "under the terms of the Public Order Regulations, a person who had attended a single FLQ meeting in the early 1960s was criminally liable." In this way, police were able to deter people from showing even the slightest support for the FLQ. Those arrested didn't have the right to see a lawyer, and although some were released in several hours, others were held for 21 days, "the full period allowed under the Act." Out of everyone who was arrested and charged, only 18 people were convicted of a crime.

Media censorship

There was also a great deal of media censorship during this time. According to Canada's Human Rights History, numerous media personalities were arrested, several people were dismissed from Radio-Canada, and student newspapers especially suffered.

And according to the Journal of Canadian Studies, there were numerous attempts by the government to "manipulate the media throughout the crisis." Some even allege that the rumor going around that the FLQ was about to start a provincial government was fabricated by Prime Minister Trudeau "to help justify the use of emergency powers."

The divided response to the War Measures Act can also be seen in the different coverage between English and French media in Québec: "French-language papers were exceedingly disturbed by what was happening to civil rights in Canada, while English-language dailies frequently argued that it was not the civil rights of Canadians that were so much in danger but the civil rights of the kidnapped victims."

Police find the Chevrolet

The following night, on October 17th, police received an FLQ communique. It read, "The arrogance of the federal government and its hireling Bourassa has forced the FLQ to act. Pierre Laporte, Minister of Unemployment and Assimilation, was executed at 6:18 this evening by the Dieppe (Royal 22nd) cell. We shall overcome. P.S. The exploiters of the Québec people had better act properly."

Police found Laporte's dead body in the trunk of a Chevrolet at the St-Hubert airport base. Ottawa Citizen reports that Laporte had been strangled, most likely "with the chain on which he wore his religious medallion." Laporte was reportedly executed in order to demonstrate that the "FLQ was serious in its demands." However, the actual events of his death are unclear, and no one knows exactly who was directly responsible for Laporte's death.

Despite the fact that some have tried to sanitize the FLQ's intentions, the Montreal Gazette writes that FLQ members took full credit for the execution, claiming that "it was not an accident." Paul Rose, brother of Jacques and another leader of the Chénier cell, once said, "I regret nothing: 1970, the abductions, the prison, the suffering, nothing." This was the first political assassination in Canada in over 100 years, and it marked the end of public sympathy towards the FLQ.

James Cross' rescue

Police engaged in a massive manhunt to find James Cross, and on December 2nd, they discovered the hideout where Cross and his FLQ captors were staying. The next day, police surrounded the home in Montreal where Cross was being kept. According to Legion Magazine, police were warned that if they attempted to raid the hideout, Cross would immediately be executed, "and they were in possession of two sawed-off .30-calibre carbines, two handguns and eight pounds of dynamite."

Police decided to negotiate with the kidnappers instead, and they agreed to give the kidnappers safe passage to Cuba in exchange for Cross' release. According to The Guardian, apparently the Canadian government "had approached two other countries to see whether they would accept the FLQ kidnappers — only to be turned down flat."

On December 3rd, Cross was released safely after over two months in captivity, ending what was surely the longest and worst birthday present of his entire life.

Continuing to hunt for the FLQ

After the public learned of Laporte's death, "public sympathy for the FLQ evaporated overnight" while police continued to hunt for FLQ members. Everyone continued to remain on edge "until the last of the FLQ members were discovered hiding on Dec. 28, and arrested," reports Ottawa Citizen. The Rose brothers was among some of the last to be discovered on December 27th. According to The Globe and Mail, Paul Rose was discovered "hiding in a tunnel under the concrete floor of a farmhouse."

The Montreal Gazette also writes that as Canadian police were desperately trying to track down members of the FLQ, the FBI was "scrambling to retrace FLQ ringleader Paul Rose's steps — and to determine whether he had fled to the United States." Rose had reportedly visited Dallas, Texas in late September/early October, and the FBI wanted to know exactly what Rose had been up to. Through their investigation, they later discovered that Rose's trip "was a mission to buy guns and raise money for the FLQ."

During the October Crisis, border authorities were on high alert. Meanwhile, the FBI looked into everyone and checked out every lead, ranging from youth communist groups in the U.S. to clairvoyants and hippies.

Aftermath of October Crisis

The October Crisis was officially declared over after the Rose brothers and Francis Simard were arrested. Along with Bernard Lortie, they were charged with Laporte's kidnapping and murder on January 5th, 1971. On February 3rd, it was revealed that under the War Measures Act, out of the 497 people arrested, 62 were charged and 32 were held without bail. However, according to the Journal of Canadian Studies, "within a month, half of them were released and the charges were dropped. In the end, only 18 people were convicted of a crime arising from the crisis." Sentences ranged from eight years to life.

Over the next two years, there were "occasional FLQ bombings, thefts, and hold-ups," but through the use of several police informers, authorities kept an eye on the remaining FLQ activities. According to Legion Magazine, by 1974, the kidnappers who'd escaped to Cuba traveled to Paris, France. However, they decided to take their chances on returning to Québec. They traveled back piecemeal: "in December 1978, the Cossette-Trudels took their chances and returned. Lanctôt and family arrived in January 1979, Marc Carbonneau returned in May 1981 and Yves Langlois in June 1982." However, they were all immediately arrested upon reentering Canada. Tried and convicted, their sentences ranged from 20 months to three years.

And by early January, all of the federal troops had left Québec, while the Public Order Act, which supplanted the War Measures Act, stayed in effect until April 1971.

What happened to Québec's independence movement?

The FLQ lost any status it had as an independence movement after the October Crisis. Many moved over to parties such as Parti Québécois, like Pierre Vallières, who "disassociated himself from the movement in December 1971 [and] recommend[ed] that all other members do likewise and support the electoral process to gain independence for Québec," according to "The Cross and Laporte Kidnappings."

In 1976, Parti Québécois came to power with 71 seats in Parliament. However, their bid to renegotiate Québec's sovereignty in 1980 was rejected "by about 60 per cent of the Québec electorate, including a majority of the French-speaking population," writes The Canadian Encyclopedia. In 1995, a second referendum was organized regarding Québec's sovereignty. It was also defeated, but this time the margin was significantly closer with 49.4 percent to 50.6 percent. Several Québec independence parties still exist as of 2021, including the Action démocratique du Québec and Québec solidaire. However, the popularity of these parties is nowhere near the level it once was.

According to The Guardian, in 2020, political parties in Québec demanded a formal apology from the federal government "its use of the War Measures Act, something the current prime minister – Pierre Trudeau's son, Justin – has declined to offer."