This Is The Most Powerful King To Have Ever Lived

Pick any of the most obvious contenders for "history's most powerful king:" Genghis Khan, Augustus Caesar, William the Conqueror, Henry VIII, and they all fall just a little bit short of being able to hold the title. They were powerful, yes. They ruled through violence or fear, they controlled a lot of territory or a lot of people or they ruled over lands that were especially influential during their time in history.

But none of those people can really claim to be "history's most powerful." The real holder of that title is someone you probably haven't even heard of, who ruled an empire you also probably haven't heard of. This king was so obscure, in fact, that history all but forgot him for thousands of years. And yet, he had more power and influence than any other king that came before or after him, and he held onto that power not through violence but through tolerance and justice.

But what about Genghis?

"Genghis Khan" is usually the knee-jerk answer to the "most powerful king" question, but there are a number of reasons why Mongolia's infamous conqueror doesn't quite qualify for that particular title. Sure, he held a lot of territory — around nine million square miles, which is twice as much as the real title-holder — but most of his territory was just empty land, so unless you count all the horses he only ruled over around 1 million subjects. So if you're using number of subjects as a benchmark for establishing a monarch's power, well, that means Queen Elizabeth II was around 130 times more powerful when she took the throne in 1953.

According to Slate, Khan's reign wasn't really long enough to score him any "most powerful" points, either. Queen Elizabeth has been on the throne for 68 years, but Khan only ruled for a couple of decades, which means you also can't really use time on the throne as a benchmark for assessing relative power.

Now just to be clear, we're not saying that Queen Elizabeth II is history's most powerful monarch, because she literally has no power, like at all. But if you just compare her stats to those of the Mongol conqueror, it becomes pretty clear that Genghis was not really as powerful as history has made him out to be.

So who was history's most powerful king?

That honor belongs to an obscure monarch by the name of Ashoka. You've heard of him, right? No? It's okay, because not a lot of people have heard of this guy. Hollywood never made a blockbuster film about him. He's not really the kind of king that the average college history professor likes to wax poetic about, either. And yet Slate says that at one time, this guy ruled over 44 percent of the world's population.

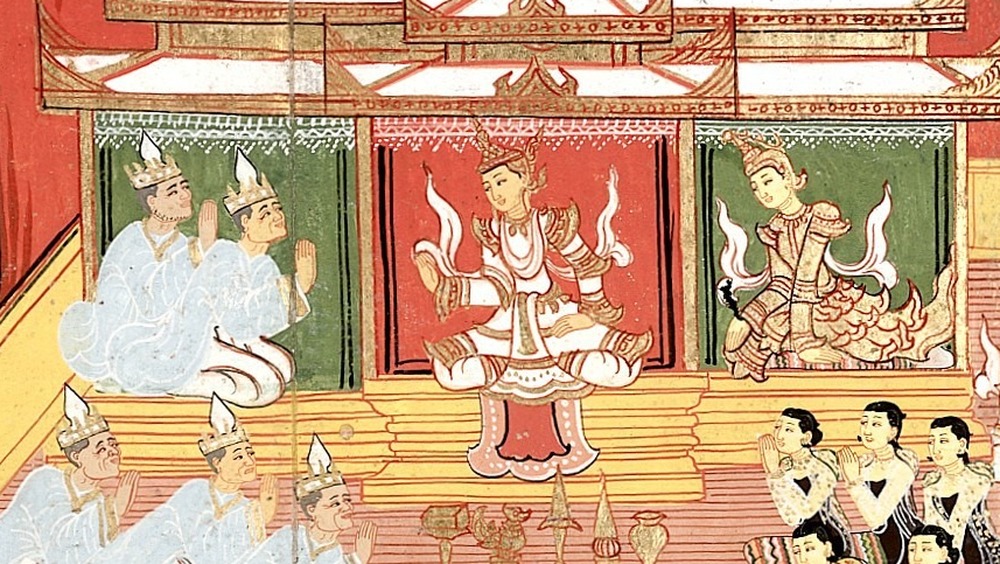

Ashoka's low-key brand of monarchy brings up an interesting question about how exactly we should define "power." You could say that power is derived from fear, and if that's true then that makes a stronger case for Genghis Khan. But while Genghis was really good at ruling with fear, Ashoka was good at winning hearts and minds, and that is its own kind of power. In fact, Ashoka's kinder, gentler way of ruling probably contributed to the longevity of his reign as well as his ability to hang onto so much territory. From 269 BC to 232 BC, Ashoka ruled the Mauryan Empire, which included everything from Iran in the northwest through Afghanistan and Pakistan, all the way through India to Bangladesh in the east. And in case you're not sufficiently wowed by the sheer vastness of his empire, at the time all of those lands accounted for roughly half of the world's GDP.

Conquering ran in the family

To be fair, the Mauryan empire wasn't all Ashoka's doing. His grandfather, a dude named Chandragupta, established it in 321 BC after Alexander the Great died and left a void in the power structure of the area. Seeing an opportunity, Chandragupta conquered Punjab, then went on to beat back another army that was invading India on behalf of the Seleucids. And since there's nothing conquerors love quite so much as more conquering, after settling things in northern India, Chandragupta went on to seize territory in the southern and eastern parts of the Indian subcontinent.

Chandragupta passed his love of land-grabbing onto his son Bindusara, who took the throne after his father's death in 297 BC and then went on to conquer even more territories in the Deccan. According to Britannica, Bindusara was so notorious that the Greeks lovingly referred to him as "Amitrochates," which means "destroyer of foes."

Bindusara ruled the Mauryan empire for a quarter century, which is a good long time for any king really, since kings all over the world were constantly under threat from things like assassination and battle wounds and choking to death on eel pies. Still, Bindusara's reign pales in comparison to his son's, who not only went on to grab even more territory but also ruled over all of it for more than a decade longer than his father did.

The young Ashoka was an unlikely king

Historical events that happened thousands of years ago often exist in multiple versions, and this one is no exception. So keep in mind that we don't really know for sure what exactly went down on the Indian subcontinent during the Mauryan Empire because CNN wasn't a thing yet, and neither was Fox News, and let's face it even if CNN and Fox News had been things we still wouldn't know what the heck was going on on the Indian subcontinent during the Mauryan Empire.

Anyway, based on what we do know it's actually pretty remarkable that Ashoka got anywhere near the throne — according to Cultural India, his mother was a commoner, and everyone knows that people with common blood can't give birth to sons with kingly potential, or something. Other sources, though, say she was the daughter of a Brahmin, and the Brahmins were way up high in the caste system. That would have made her a perfectly worthy mother to an emperor, except that Bindusara just didn't like the son he had with her all that much. Either way, Ashoka was already not really considered a contender for the throne, but he also had several older half-brothers, so his father had plenty of heirs to choose from without having to consider the one he disliked.

Who needs royal blood when you can kill a lion with a stick

Ashoka did have a couple of non-blood and non-birth order related things going for him. First of all, at least according to ThoughtCo., he was a mean kid. And not just a "takes other kids' ice cream cones" kind of mean, either. Ashoka was cruel. While other mean kids might waste their afternoons burning up bugs with a magnifying glass, Ashoka chose larger targets. Once, according to legend, he killed a lion. With a pencil. Okay it was actually a stick, and it was maybe slightly larger than a pencil, but still, you have to be pretty cruel to kill a lion with a stick and you also have to be super badass to pull that off without, you know, dying.

So anyway, Ashoka had quite a reputation and despite not really being his father's favorite son, he did make enough of a name for himself that Bindushara let him do stuff like squash a rebellion at the tender age of 18. In one version of Ashoka's life story, his father also appointed him Governor of Avanti, which was a pretty big deal for the least favorite son since Avanti was a prosperous kingdom that was also an important part of the Mauryan empire. So that was great for Ashoka, but meanwhile his brothers back home were starting to worry about their competent but mean younger brother and his potential place in the line of succession.

I'm exiling you, just kidding please help me end this uprising

So things were going pretty swimmingly for Ashoka until his brothers became so jealous and afraid of him (specifically, of his potential to become the heir apparent) that they convinced Bindusara to exile him for real. For some reason, the emperor didn't see through their petty whining and did what he was told, sending Ashoka off to Kalinga on the east-central coast of India. Kalinga wasn't even part of his father's domain at the time, but Ashoka still managed to do okay there — in fact in Kalinga he met and married a fisherwoman named Kaurwaki. He did already have at least one other wife, but never mind, that's how things were done in that time and place so we're just not going to comment.

Anyway, unfortunately for Ashoka's half-brothers, kings who do a lot of conquering tend to have subjects that occasionally rebel, and that's exactly what happened in Ujjain while Ashoka was busy being exiled. Recognizing that he needed help to quash the uprising, Bindusara summoned Ashoka back from exile, and Ashoka rewarded his gamble by successfully ending the rebellion.

At some point Ashoka became a Buddhist ... sort of

Ashoka's victory in Ujjain didn't come without cost — According to ThoughtCo., the prince was wounded in battle and ended up in the care of local Buddhist monks. The monks were partly concerned with helping Ashoka recover and partly concerned with hiding him from his older brother Susima, who was still the heir to Bindusara's throne and very much out to get him. Anyway, this version of the story says that Ashoka converted to Buddhism while in the care of the monks, though another version says he was introduced to Buddhism by his wife Devi, who was not that other wife that he met while he was in exile but a totally different wife, or possibly not a wife at all, depending on who you ask. Either way, the two of them had two children together — a boy and a girl — and the son went on to become a Buddhism rock star (well actually, he just led a Buddhist mission to neighboring Sri Lanka, and that's about as rock and roll as Buddhism ever gets).

At the time, Buddhism was still pretty obscure so Ashoka's decision to convert was likely a really big deal, though that precise moment has kind of gotten mixed up in all the different retellings. At any rate, it was an important turning point for the future king and part of what contributed to the power he was able to wield later in life.

That's kind of hardcore for a Buddhist isn't it?

Eventually Bindusara ended up on his deathbed as people often do, but despite everything his younger son had done in his name, the old king still wanted Ashoka's brother Susima to succeed him, even though Susima was petty and paranoid and no one liked him. Well, it's not actually super obvious how popular Susima was but according to the Ancient History Encyclopedia he was at least heavily disliked by Bindusara's ministers, who plotted to install Ashoka on throne after the emperor finally got on with the business of dying. Anyway, when the dust cleared it was Ashoka on the throne instead of Susima.

What happened next is kind of out of character for a Buddhist. Ashoka's brothers weren't very happy with the turn of events and his ascension was followed by a two-year war. Ashoka was victorious, and he punished Susima by having him executed. It wasn't an especially merciful execution, either — Susima was evidently burned alive in a charcoal pit, so that probably sucked for him. That's not all, though, Ashoka had somewhere between three and 99 brothers (depending on which version of the story you believe) and he had them all murdered, except possibly the youngest one who decided to just renounce his claim to the throne and become a Buddhist monk, because at that point becoming a Buddhist monk probably sounded pretty danged awesome compared to the alternative.

Ashoka's big come-to-Buddha moment

Once Ashoka was settled onto the throne, he figured that he probably ought to carry on doing what his father and his grandfather had been doing. There wasn't a whole lot of the Indian subcontinent left to conquer, though, except for the southernmost tip of India and Kalinga, his old stomping grounds in the east. So eight years after he became emperor, Ashoka launched a shiny new war campaign and at the end of it became the proud owner of one seaside territory and like 200,000 corpses.

According to PBS, Ashoka found the truth about the battle and its hundreds of thousands of casualties too much to bear. He later wrote of feeling "deeply pained by the killing, dying, and deportation that take place when an unconquered country is conquered." And meanwhile all the people who didn't die in Kalinga were all, "Um, okay cool but why did you need to personally cause a bunch of killing, dying, and deportation before it finally dawned on you that killing, dying, and deportation sucks?" His change of heart was also a bit strange given that he was also said to have personally executed something like 500 political rivals during the war that preceded his ascension, and for some reason all that killing never troubled him. So yeah, he had his come-to-Buddha moment a bit too late for 200,000 plus people but at least he swore off violence permanently after it was all over.

Spreading the word of Buddha

So after the Battle of Kalinga, Ashoka basically went around telling everyone how awesome Buddhism was, and people mostly listened — except maybe for a random few people in Kalinga who were like, "Oh sure now the dude that killed all my friends and family wants me to embrace his message of peace, whatever." But Ashoka wasn't just blowing smoke. He'd had a genuine change of heart and had made it his mission to use his great power and influence to spread the message of Buddhism across India.

Now, most ordinary people who embrace religion and adopt a missionary life only manage to reach a handful of people, but Ashoka ruled over nearly half of the world's population, so that made his job a lot easier. According to the Hindustan Times, he didn't just spread the word of the Buddha throughout India, he also sent emissaries to places like Greece, Syria, and Sri Lanka. It was his patronage that helped transform Buddhism from a relatively obscure religion into one of the more dominant faiths on the Indian subcontinent.

Ashoka practiced what he preached

It's easy enough to tell people about your religion but not everyone is so good at practicing what they preach. Ashoka, though, did seem to genuinely believe what he was telling people, or at least was smart enough to be a Buddhist king in action as well as in word. He worked hard to spread Buddhism across the realm, but he didn't force it on anyone. In fact, according to National Geographic, he had a pretty strict policy of religious tolerance, which you don't usually expect to see in the ancient world.

He was also smart enough to know that if people are going to listen to you, you have to speak their language — literally. One of the things Ashoka is most remembered for is the edicts he had carved into stone pillars and other monuments across his domain, always in the local dialect.

Ashoka could have just been preachy without really doing anything to help anyone, but he also seemed to genuinely care about his subjects. He ruled with kindness, and would often travel his domain to make sure that his subjects were okay, or as okay as anyone can be if they were mostly poor and living in the third century BC. And he did work towards improving everyone's living conditions, too — in addition to all the new Buddhist temples he put up, he also built and maintained roads and helped bring irrigation to dry places.

It didn't last

Ashoka worked pretty hard to build a prosperous, peaceful realm, but it didn't last. According to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, the Mauryan empire collapsed less than 50 years after Ashoka's death. Its demise doesn't seem to have had anything to do with Ashoka's peaceful policies or his strength as a ruler — it was more due to the fact that the empire was divided up amongst his grandsons and it just kind of fizzled out. And because Ashoka didn't do anything really scandalous like play the violin while his city burned or have a scorching affair with an Egyptian queen or something, his whole 40-year reign was kind of just forgotten. For a couple of thousand years.

Ashoka's story was preserved in obscure religious texts that were compiled a few hundred years after his death, but like Buddhism itself those stories sort of faded from Indian consciousness over the centuries. In fact, if it wasn't for the edicts Ashoka had carved into stone pillars, he might have been forgotten forever, but in 1833 a British Scholar named James Prinsep got curious about all of those stone pillars, and made it his mission to figure out what they said. With the help of a scholar of Buddhist history, Prinsep found the name Ashoka in an ancient religious text and connected him to the author of the pillar inscriptions. So today, we finally know the name "Ashoka." Sort of. If only Hollywood would make a blockbuster movie.