The Crazy True Story Of The 1910 Los Angeles Times Bombing

Over the course of four years in the early 1900s, the International Association of Bridge and Structural Iron Workers was allegedly behind over 70 dynamite attacks across the United States. While these explosions were aimed at anti-union businesses, they were typically designed to go off when people wouldn't be around.

However, that's tragically not what happened with the bombing of the Los Angeles Times building in 1910. And although the century was just a decade in the making, its subsequent trial was heralded as the "crime of the century."

Ultimately, the dynamite campaign did little to advance the cause of the labor movement in the United States. And although a commission created to investigate labor relations found the working conditions in the country to be little better than feudalism, the commission was derided as too liberal and ignored. As a result, it took decades for people to see any improvement in their working conditions. And over a century later, the dynamite campaign continues to be blamed for ruining the labor movement. This is the crazy true story of the 1910 Los Angeles Times bombing.

The Los Angeles Times vs. unions

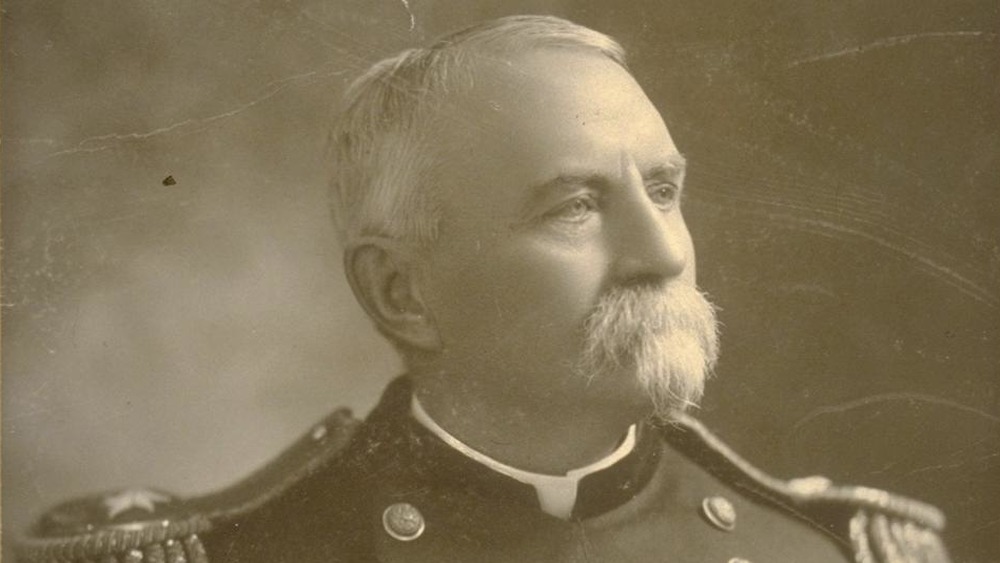

In the summer of 1910, the city of Los Angeles witnessed a series of labor strikes as workers in the city tried to unionize. One of their fiercest opponents was Harrison Gray Otis, publisher of the Los Angeles Times, according to Crimes of the Centuries. After gaining control over the local Merchants Association (MMA) in 1896, Otis "launched a campaign to remove the remaining unions within the city," using The LA Times as his mouthpiece.

It was in response to Otis' anti-union rhetoric that "a unionization campaign was initiated by 1,500 Iron Workers in the spring of 1910." And after the ironworkers and members of other unions began striking, Otis and a few other local businessmen conspired with the Los Angeles City Council to prohibit picketing, according to "McNamara Bombing Case."

In Bridges of Reform, Shana Bernstein writes that "Otis remained committed to the idea that an open shop was a crucial precondition for drawing business to the city and turning it into a major metropolis," in which an open shop refers to a place of employment where "union membership is not a requirement for continued employment." Otis was also concerned with making Los Angeles "the 'white spot' of the nation," which involved ensuring that the city was aesthetically, morally, politically, and racially pure.

Anti-picketing ordinances

The no-picketing ordinance was passed on July 16th, 1910, and the Los Angeles Police Department really took the new ordinance to heart. According to the Los Angeles Almanac, police had been given the authority to arrest "picketers and persons 'speaking in public streets in loud or unusual tones,'" and they promptly arrested hundreds of labor activists. But HistoryNet writes that "unions picketed anyway, quickly springing 472 arrested strikers by paying their $100 fines." And unions only grew in popularity, with union membership in Los Angeles increasing by 60 percent.

Meanwhile, Harrison Gray Otis kept calling union organizers "gorillas" in the editorial pages of his paper. Apparently, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) considered Otis such an "impediment to unionization" in the United States that in 1907, they passed a secret resolution for "a war fund for use in attacking the Los Angeles Times."

In "McNamara Bombing Case," Michael Hannon writes although the ordinance was later challenged in California's Supreme Court, "despite some misgivings, the court upheld the ordinance."

Pro-union San Francisco

The battle over unions in Los Angeles actually began up north in San Francisco. According to "McNamara Bombing Case," in 1901, San Francisco's labor organized movement was almost completely suppressed, but they "overcame this threat and so effectively captured the political system that their party won the mayoral election, gained control of the city purse strings and the police department." According to FoundSF, "the election provided, in a sense, a referendum regarding the policies of the Employers' Association and the right of unions, not merely to organize, but to establish the closed shop [...] The second, and more important issue, was one of who should control the city government, labor or capital."

The election of Mayor Schmitz gave labor strikes in San Francisco a significantly different flavor than those in Los Angeles. During the Carmen's strike against the United Railroads, "the general manager tried to intimidate the strikes by hiring armed guards to ride the streetcars, but Mayor Eugene Schmitz refused to issue permits to carry weapons." In the end, the strike lasted a week and ended with "a favorable settlement" for the union.

As San Francisco became "the first and only closed shop-city in America, where only union members were allowed to work," Los Angeles became "Otistown of the Open Shop." But since it was cheaper for employers to exploit workers in Los Angeles, the disparity was unsustainable, and workers in San Francisco sought to help workers in Los Angeles unionize as well.

Bombing the Los Angeles Times

Roughly an hour after midnight on October 1st, 1910, a bomb went off in the building of the Los Angeles Times. According to Crimes of the Centuries, the bomb went off roughly three hours too early; it was supposed to explode when the building was empty "but failed to do so based on a faulty alarm clock."

Vanity Fair writes that almost 100 people, "the newspaper's late-night editorial and composing staff," ended up trapped in the building as it crumbled. The six explosions of dynamite leveled half of the building, and "the natural gas lines that created a fire upon detonation [destroyed] the remainder of the Los Angeles Times building and a neighboring building, which housed the Los Angeles Times' printing press." And according to Los Angeles Almanac, the "several tons of stored ink" also quickly ignited and consumed the building. Twenty people died as a result of the bombing and 17 more were injured. At the time, it was "the biggest fire the city of Los Angeles had ever seen."

Later that morning, timed explosives were also found next to Harrison Gray Otis' home as well as the home of Felix Zeehandelaar, secretary of the MMA. Only one of the bombs ended up exploding after it had been removed by a policeman, while the other "never exploded and yielded important clues for investigators," according to "McNamara Bombing Case."

William Burns on the case

Originally, William J. Burns was hired to find out who was responsible for the bombing of the Los Angeles Times building. HistoryNet writes that one month before traveling to Los Angeles, Burns had been hired to investigate another explosion at a rail yard in Peoria, Illinois, and was still investigating it when he traveled to Los Angeles to give a speech. When Burns arrived in Los Angeles, he wasn't aware that a bombing had occurred until his taxi passed by the Times building on the way to his hotel. Once there, Burns was contacted by Mayor George Alexander, who "begg[ed] Burns to investigate the bombing."

Burns was already a famous detective, but according to "McNamara Bombing Case," some considered his involvement controversial. Before the bombing, Burns was part the prosecution of a corruption investigation in San Francisco from 1905 to 1908, "which pitted anti-union forces support by Otis against labor forces [... and] because of the negative fallout generated by the graft cases, Otis and the MMA denounced the hiring of Burns."

Harrison Gray Otis and the MMA wanted their own investigator, so they hired Earl Rogers, who coincidentally had been "hired to defend one of the most important defendants in the graft investigation." Although there was some resistance, eventually the two decided to cooperate on the investigation.

Christmas bombing

The investigations of Burns and Rogers weren't getting very far until Christmas Day, when there was another bombing in Los Angeles. According to "McNamara Bombing Case," dynamite was set off at Llewellyn Iron Works, roughly a mile away from where the Los Angeles Times building had been. Initially, Baker Iron Workers and another building of the Los Angeles Times were meant to be bombed as well, but those plans fell through since the bomber "found Los Angeles too dangerous."

HistoryNet writes that the explosion injured one watchman and caused up to $25,000 worth of damage. But as Burns noticed the similarity of the bombings with that of the explosion he'd been investigating in Illinois, he started putting the story together. Burns kept investigating into 1911, and as bombs struck "ironworking shops and iron mines in Illinois, Indiana, Nebraska, and Ohio," more and more pieces began falling into place.

Tracking down the McNamera brothers

By spring of 1911, William Burns discovered that James B. McNamara and Ortie McManigal were involved in the bombing and on April 14th, 1911, the two of them were arrested in Detroit. According to HistoryNet, when police checked their suitcases, they "found a dozen explosive devices identical to those used in Peoria and Los Angeles," which were apparently meant to be used somewhere in Michigan.

According to "McNamara Bombing Case," Burns got McManigal to give a full confession in exchange for immunity not only about the Los Angeles Times bombing, but about "his knowledge and participation in a dynamiting campaign waged across the country by the International Association of Bridge and Structural Iron Workers (IABSIW)." Initially, it was believed that McManigal was simply a gifted liar, but "upon investigation the story checked up in every detail as to time and place of the explosions." In his confession, McManigal also implicated James B. McNamara's brother, John J. McNamara, as the leader of the bombing operation.

Around April 22nd, John J. McNamara was arrested in Indianapolis. In the basement of the American Central Life Building, police found "200 lbs. of explosives, percussion caps, fuse coils—and 14 alarm clocks identical to those used in the Los Angeles and Peoria bombings."

Clarence Darrow takes the case

Initially, those who were in the pro-worker movement refused to believe that the McNamara brothers were responsible for the bombing. And in addition to the AFL's fierce belief that the McNamara brothers had been framed, the manner of J.J. McNamara's arrest was also considered incredibly questionable.

In "McNamara Bombing Case," Hannon writes that many union leaders described his arrest as a kidnapping. Neither the extradition laws in Indiana nor California were followed, and the extradition request was made based on a false statement, which was done "to get J.J. McNamara out of Indiana as quickly as possible to prevent a union attorney from filing habeas corpus." Although those who were accused of kidnapping McNamara were arrested, "a grand jury refused to indict most of those arrested" and others had their charges dismissed.

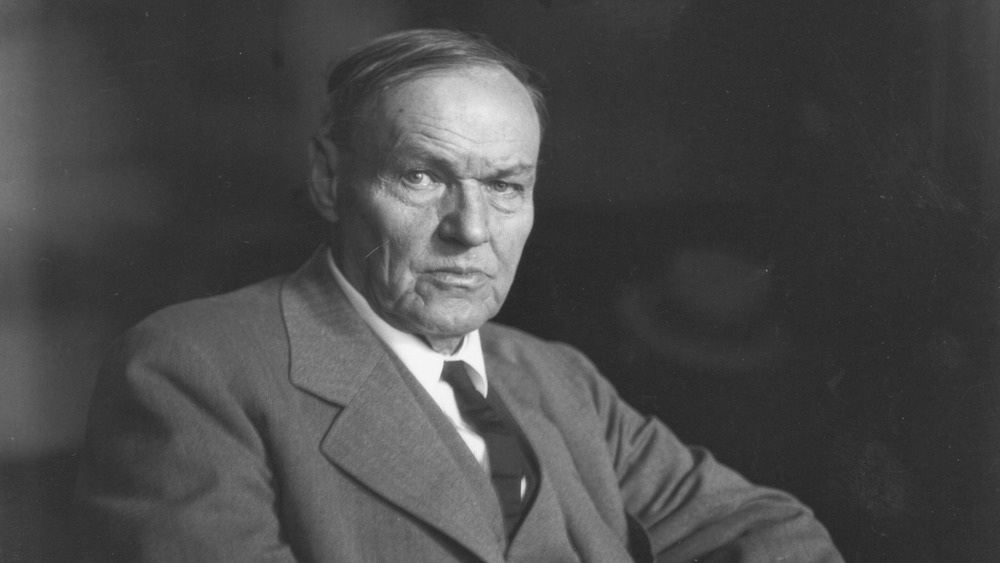

Clarence Darrow, who'd later become famous for his involvement in several pivotal trials, was hired to defend the McNamara brothers. Initially, Darrow didn't want to be involved in the trial, but he was convinced by Samuel Gompers. He "required a $50,000 retainer and eventually charged $200,000 for the case." But before long, Darrow was convinced that his clients were going to get the death penalty. There was an enormous amount of evidence against them, and Darrow was unable to find any loopholes in McManigal's confession. Prosecutors even had "letters from John McNamara to James ordering attacks."

Taking a plea deal

Seeing how dire his case was, Clarence Darrow doubled-down on bad ideas and decided to bribe someone who was going to be on the jury. According to "McNamara Bombing Case," he made several attempts to bribe jurors using investigator Bert Franklin, but Franklin was discovered and arrested on November 28th, 1911.

Although news of the bribe quickly "spread across the country," Darrow's involvement was initially kept quiet. But unfortunately, knowledge of the attempted bribery meant that the defendants now stood an even worse chance in front of a jury. The deadline for their plea deal was set for December 1st, 1911, and on that day, James. B. McNamara and John J. McNamara pled guilty to bombing the Los Angeles Times building and the Llewellyn Iron Works, respectively. Avoiding the death penalty, James was given life in prison while his brother was sentenced to 10 years imprisonment.

However, according to the University of Cincinnati, the defense wasn't the only one who engaged in jury tampering: "During the trial, both the defense and the prosecution allegedly engaged in the threatening of witnesses, and tampering with evidence." But Smithsonian Magazine reports that in January 1912, "Darrow was arrested and charged with two counts of bribery." Earl Rogers, who was once leading the investigation into the Los Angeles Times bombing, defended Darrow in these two trials, one of which ended in an acquittal, the other in a hung jury.

Labor loses the election

As preparations for the trial were going on, Los Angeles was in the middle of its 1911 mayoral election. According to HistoryNet, "the primary was October 31st; the election, December 5th," and the candidates were split between pro-workers and pro-business. Job Harriman, who was also Darrow's co-council, was running as the Socialist-Labor candidate against Democratic incumbent George Alexander, who was heavily backed by Otis "and the business bloc."

In "McNamara Bombing Case," Hannon writes that "It is difficult to overestimate the demoralizing effect the plea deal had on McNamara's labor supporters. Labor supports across the country felt betrayed and it sent the labor movement into turmoil. Not only had they supported the McNamaras vocally, but they had contributed their hard earned money for their defense."

Although the race had been close before the plea deal, with Harriman unexpectedly surging during the primary, the plea deal destroyed his chances and gave Alexander the surge he needed to defeat Harriman: "Because of the plea deal, Harriman ended up losing by 20,000 votes." Ultimately, this set the pro-worker labor movement in Los Angeles "back 20 years."

Federal trials for nationwide bombings

In February 1912, the federal government also decided to pursue charges against the Iron Workers Union. "McNamara Bombing Case" writes that "a federal grand jury in Indianapolis indicted 54 union men for a nationwide campaign of bombings."

According to "Ironworkers: A History of the Iron Workers Union," 39 people were found guilty on all counts of conspiracy "to commit an offense against the United States" and of transporting nitroglycerin and dynamite on passenger trains. The sentences ranged from one to seven years for almost all of the defendants. Seven of the defendants ended up having their convictions reversed, while Frank M. Ryan, General President of the Iron Workers Union, had his sentence commuted by President Woodrow Wilson.

At the time, the trial was considered the "largest criminal conspiracy trial" in the history of the United States. There were almost 700 witnesses in total, 5,000 pages of exhibits, and 21,000 pages of testimony. And during the trial, "the defense was not allowed to introduce evidence of employer mistreatment as a defense of provocation."

At what cost

Unfortunately, the dynamite campaign was literally more expensive for the pro-labor movement than it was for the businesses it was targeting. The trials alone cost $150,000 without even including individual contributions to the McNamara defense fund. And when factored into the costs of the explosions, "each explosion ended up costing the union about $2,000 [while] most of the explosions caused about $1,000 or less of damages and some of the larger businesses had dynamite insurance."

In The National Erectors' Association and The International Association of Bridge and Structural Ironworkers, Luke Grant writes that the union also continued to pay its imprisoned members $25 per week, "so that from a financial point of view the dynamite campaign must be considered a failure for the union."

Meanwhile, according to FBI History, William Burns would go on to be the first director of the Bureau of Investigation, the first iteration of the FBI.

Legacy of the dynamite bombings

The dynamite campaign also led President Taft to create a Federal Commission on Industrial Relations, although President Wilson would be the one to choose the members of the commission. The report stated that in general, "industrial feudalism is the rule rather than the exception" in the United States and that action should be taken immediately to work towards creating systems of industrial freedom instead: "The entire machinery of the Federal Government should be utilized to the greatest possible degree for the correction of such deplorable conditions as have been found to exist." But unfortunately, the report was seen as having "liberal leanings" and "Congress was upset enough to cut off its funding," according to "McNamara Bombing Case."

For many of the union ironworkers, National Erectors' and International Ironworkers reports that "the entire [dynamite] campaign was [considered] a serious mistake, which cost the organization a great amount of money and loss of prestige, with few compensating returns. An occasional job here and there was unionized, but on the whole dynamite as an organizing force failed to accomplish the main purpose for which it was intended."

James B. McNamara ended up dying in San Quentin from cancer on March 9th, 1941 after refusing to file any parole requests. John J. McNamara died two months later in Butte, Montana on May 8th.