Here's How Ireland Really Celebrates St. Patrick's Day

In the U.S., St. Patrick's Day, on March 17, is a way for the country's 34.5 million Irish-Americans (and those who just like wearing green and drinking Guinness) to do what many of us wish we were doing the rest of the year: reveling in the streets drunkenly under the protection of sanctioned noisiness. It's a time for wearing those funny hats with the buckles on the front, painting your face in green streaks, hefting drinks to the sky, attempting cringe-y Irish accents, proclaiming love for Boston, and of course: pretending to be Irish if only for a day (whatever "Irish" now means in the U.S.).

But what about back in Ireland itself? The population of Ireland is seven times smaller than the population of Irish-Americans, per the Washington Post. Are they all donning their green apparel and chugging Guinness in a dire attempt to obliterate their shame and short-term memory? Or is St. Patrick's Day in the U.S. one of those pure Hallmark fabrications used to drum up sales between Valentine's Day and Easter? Are its "traditions" a bunch of nonsense that generationally removed posers use to pretend to be anything other than Seamus O'Toole, rank-and-file "American"? Was there anything that the original Irish-American immigrants once did that Irish people also do to celebrate this traditional holiday?

All valid questions. And the answer to all of them is: yes. Some things have changed over time, some are fabricated, and some are legit. But St. Patrick? Wasn't even Irish.

A day to commemorate St. Patrick's role in spreading Christianity through Ireland

To understand St. Patrick's Day in Ireland, we've got to go back to the source: St. Patrick (then only "Patrick"). Patrick was born around 400 CE in Britain (the continental area of modern-day England and Wales) to a wealthy family. His father took on the job of church deacon for tax incentives, as History explains. Patrick was, ironically, captured by Irish raiders and carted off to slavery in Ireland (the exact location is disputed).

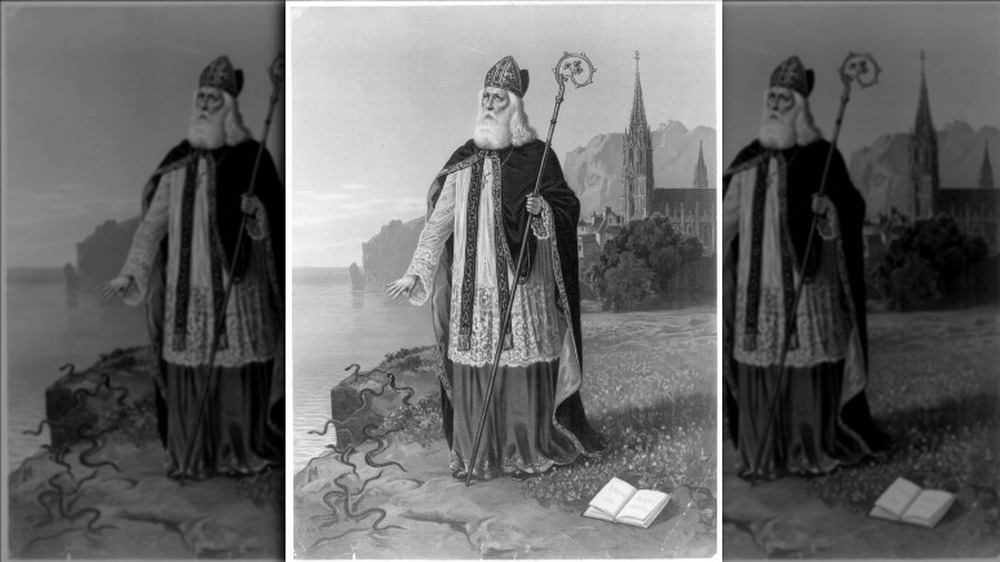

There, while engaged in pastoral work like shepherding, he took to religion for comfort, had a vision from God, and escaped back to Britain. He became ordained, and then returned to Ireland as a missionary. During that time grew a whole slew of tales about him — largely apocryphal, as Britannica outlines — such as Patrick chasing all the snakes of Ireland into the ocean (Lucifer was a snake in the Adam and Eve story, remember), summoning a herd of pigs to feed some poor people, and resurrecting the dead (Patrick's claim). Overall, Patrick was credited with the spread of Christianity in Ireland, or as he said it, worshipers of "'idols and unclean things' had become 'the people of God.'"

According to Biography, Patrick was never officially canonized — declared a saint — by the Church, though it wasn't unusual in the first millennium for someone's holiness to be generally recognized as "saintly."

A divergence, and now convergence, of traditions

Patrick died March 17, 461 CE, per History. The day, a solemn affair having nothing to do with parties or parades, was commemorated in his honor.

Fast forward to 1737 CE, as Business Insider explains, and we've got the first Irish parade in Boston. From that point, St. Patrick's Day in the U.S. started changing from a religious holiday to a non-religious "this is what it means to be Irish" day. In the 19th century, Irish Catholics faced discrimination from Protestant Americans, and boom: cue the whiskey shots, giant leprechaun floats, green dollar-store kitsch, shamrock pins, and so on, as an attempt to foster solidarity among the Irish-American population.

Eventually, all of this across-the-pond friendly mayhem made its way back to Ireland, where as late as the 1970s, St. Patrick's Day was such a serious, religious event that even pubs were closed on March 17. To frame this significance properly: pubs in Ireland only close on holidays such as Good Friday, Easter, Christmas, and various other bank holidays through the year, as Tourism Ireland says.

It took all the way to the 1990s, over 1,500 years after the death of St. Patrick, for anything remotely similar to the U.S. celebration of St. Patrick's Day to happen on the Emerald Isle. In an attempt to boost tourism and the economy, the Irish government started sponsoring festivals, parades, performances, and the like, starting in Dublin. Now, St. Patrick's Day in Ireland doesn't look too dissimilar from the U.S.

A day for parades, shamrocks, and other green things

Nowadays, a transplant from New York or Boston visiting Ireland on St. Patrick's Day would, essentially, fit right in (and yes, this includes Northern Ireland, which is a part of Great Britain). There are some differences, though.

Pubs and Guinness are, without any degree of exaggeration, the heart of St. Patrick's Day in Ireland, along with parades and music. But please don't order an "Irish Car Bomb" (an old domestic terrorism reference from "The Troubles," 1968-1998) or a layered Guinness-and-Bass "black and tan" (an old reference to British paramilitary clothing), per Vinepair.

Do partake in parades, and yes, wear green, as Your Irish explains (even though for centuries the color of St. Patrick was blue). Lots of parades in Ireland have cool, pagan-inspired costumes like antler-headed forest creatures, so get creative. But, don't pinch anybody. That strange custom started when locals in the U.S. tried to guilt their cohorts into wearing green if they weren't getting in the spirit. Also, don't wear one of those stupid "Kiss Me, I'm Irish" shirts. Instead, wear a shamrock, but try to pin an actual shamrock (like the plant) to your clothing.

And finally, don't try to self-identify as "Irish" because your grandma says her father's mother landed in the U.S. from County Clare in 1890 or something. Real Irish people, though they've adopted U.S. St. Patrick's customs, will, in true Irish fashion, mock you mercilessly.