Bizarre Reasons People Could Be Excommunicated

Excommunication is one of those practices that a lot of people have heard about but might not really understand. It's not actually a condemnation to Hell and eternal suffering, says New Advent, it's more of a sort of kick in the backside that's — in theory — a temporary measure designed to get someone who's screwed up royally to make amends, change their ways, and get back in line with the church's thinking.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the practice of excommunication led to a ton of abuses and a lot of debate. It's supposed to be reserved for only the worst sins and offenses against the church, and it hasn't always been clear just what's worthy of excommunication. That's led to the organization of councils throughout the centuries, that were put together to decide just why a person might face excommunication, and why.

And over those centuries, well, let's just say that times have changed. There's been a lot of super weird reasons that people have found themselves excommunicated from the church, and some of them are pretty epic. This isn't your standard "taking the Lord's name in vain," sort of offense, this is the stuff of action movies and suspense thrillers.

The city that was excommunicated... for a lie

Excommunication isn't just for people — it's also for cities. According to Fodors, Trasmoz, Spain, was a bustling city of around 10,000 people when it was excommunicated en masse in the 13th century. Trasmoz is nestled in the Moncayo mountains, and it's not just surrounded by beautiful scenery, it's also surrounded by extensive silver and iron deposits. It wasn't long after the Castle of Trasmoz was built that the powers-that-be realized their rich mines and remote location made it the perfect place to counterfeit some coins, so that's exactly what they started doing.

In order to keep anyone from sniffing around, they started the rumor that the castle was actually home to a group of powerful witches and warlocks, who would do what witches and warlocks do best to anyone caught sticking their nose where it didn't belong. Rumors reached the abbot of Veruela, who already didn't like Trasmoz on general principles: they weren't until the church's control, and therefore, didn't donate any of their wealth.

So, he excommunicated all of them. Trasmoz doubled down, and by the time King Ferdinand II stepped in, the two sides were on the verge of all-out war. The king ruled in favor of Trasmoz, but under the guidance of Pope Julius II, the church cursed the area. Today, the BBC says there's only about 62 people living there, and not only has the church refused to lift the curse, but now, they actually do embrace their witchy roots.

Want to be pope? Don't tell anyone, because...

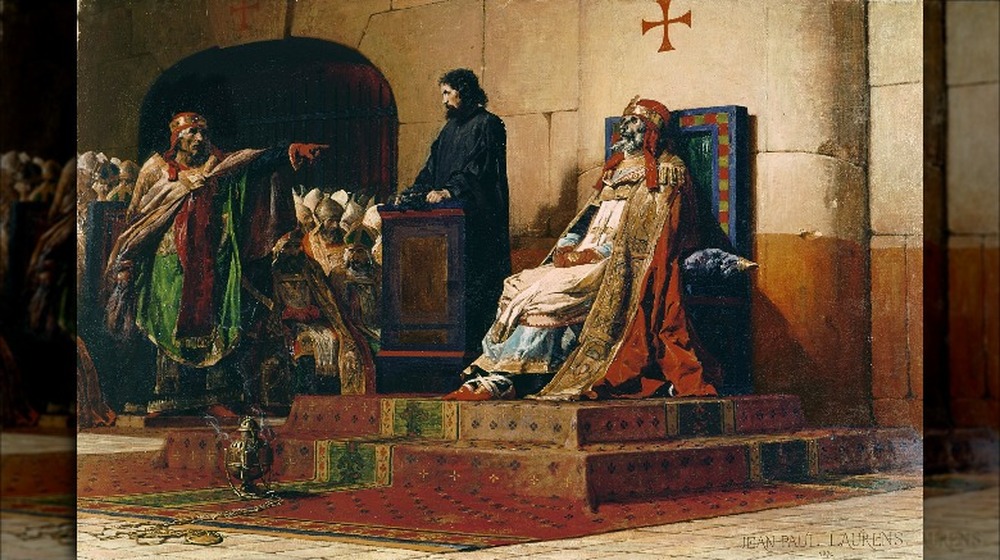

One of the strangest sagas in the church's history has got to be the Cadaver Synod of 897. That's when Pope Stephen VI had the dead body of his predecessor, Pope Formosus, disinterred, re-dressed in all his papal finery, and plopped down on a throne in San Giovanni so Stephen could hurl accusations at the dead man during a "trial" that ultimately resulted in a guilty verdict. Formosus was defrocked, had his blessing fingers cut off, and eventually chucked into a river (where he was later found by an undoubtedly very surprised fisherman).

Here's the part related to excommunication: In 876, Formosus had been excommunicated by then-Pope John, because he'd been working with a Frankish king who'd set his sights on becoming King of Italy. According to National Geographic, Formosus was brought back into the fold in 883, and he was restored to his original position.

The political landscape descended into complete anarchy, and after Formosus died in 896, Pope Stephen VI wanted to make his allegiances known — and that involved excommunicating a dead man. He needed a reason, though, and for that, he went back to some oldies but goodies: charges of perjury, and aspiring to become pope. Medievalists says that kind of ambition was an excommunicable offense, and while there was undoubtedly more to it, well, that was enough for Stephen VI.

Accepting a slave into a monastery

Establishing the accepted beliefs and foundations of the Christian church wasn't just "The Ten Commandments, Easter, He has Risen, and Hallelujah," there was a lot of arguing and debate at first. According to Britannica, the Council of Chalcedon in 451 was called to approve doctrine and creeds, and decide what offenses were serious enough to get people kicked out of the flock. One of those had to do with slavery.

It's not what you think.

The council decided (via Papal Encyclicals Online) that, "No slave is to be taken into the monasteries to become a monk against the will of his own master. We have decreed that anyone who transgresses this decision of ours is to be excommunicated..."

That sounds horribly cold, and the council did give a reason... sort of. It wasn't because they were afraid they were suddenly going to have a whole lot of monks who were ex-slaves that realized a life of solitude and chastity wasn't so bad when hard labor was the alternative, it was because monasteries were forbidden from doing anything that would "interfere, or take part, in ecclesiastical or secular business." Basically, that's just a way of saying slaves weren't their concern.

Hiring assassins can get you excommunicated

The First Council of Lyons met in 1245, and according to Papal Encyclicals Online, among the topics of conversation was the assassination of the duke Ludwig of Bavaria, a devout Christian whose death, they said was caused by "the deadly and hateful service of other unbelievers against the faithful."

From there, the council turned to the topic of hiring assassins, and decided that anyone who hired an assassin was subject to excommunication... but not because of the whole murder aspect of it.

The idea was that high-ranking, important people who knew they would be the potential target of as assassination plot might do things to appease the would-be assassins and ultimately save their own lives, even if it meant going against the doctrine of the church. That was the sort of thing that would condemn a person's soul, so a promise to excommunicate the people who hired assassins was seen as a sort of spiritual protection for those potential targets who would — ideally — be able to go about the Lord's work without fear.

Doctors healing? We can't stand for that sort of thing

A doctor's entire job is to make people better, but according to the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215 (via Papal Encyclicals Online), it was exactly that sort of thing that they could also be excommunicated for.

Why? At the time, there were numerous illnesses that were believed to be handed out by a wrathful God who wanted to punish people. Sicknesses like the plague were heralded as a sign of a corrupt community, and while the plague was often a death sentence, there were plenty of times that a doctor could step in and make things better.

The problem with that was that the church decided that kind of relief and healing was in direct opposition to God's will, and they couldn't be having any of that. Hence, the excommunication rule, and an additional decree that before treating a patient, a doctor was technically supposed to call "physicians of the soul" to find out if they were dealing with a God-sent illness, or if they could go ahead and help their sick patient.

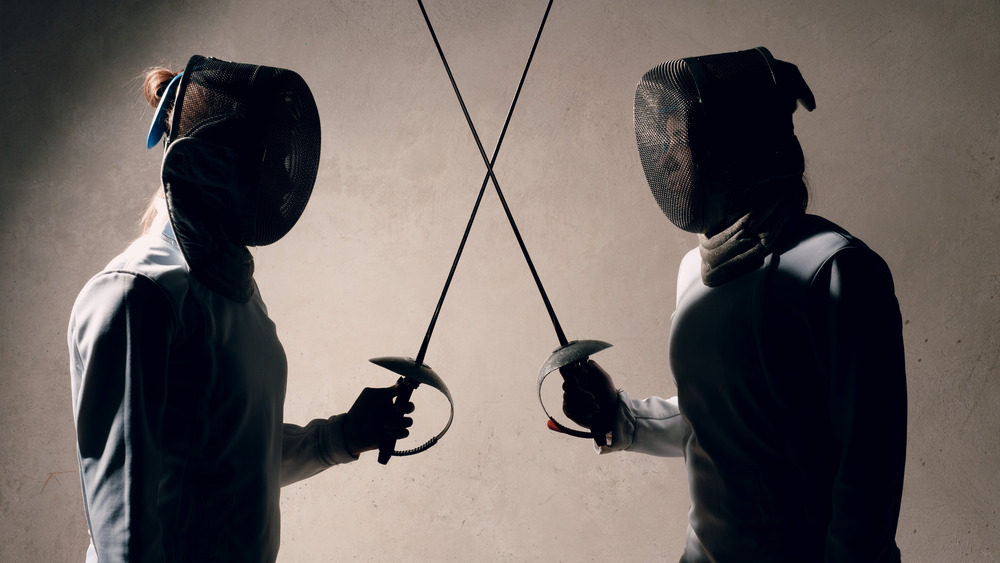

The fall from grace of a divine punishment

Dueling, says New Advent, has something of a storied history within the church. At first, it was seen as a way of setting a dispute that God had a very real — and final — hand in, as the winner and loser was thought to be selected with some divine guidance. By the 9th century, the church was slowly admitting that maybe God didn't have anything to do with deciding the outcome of duels after all, and by the 15th century, they were firmly of the stance that they were going to have none of this revenge-and-honor stuff.

Once they decided they hated it, they went all out. After the Council of Trent, dueling became an excommunicable offense that "the Devil had originated" as a way to kill the body and destroy the soul. Anyone killed in a duel wasn't allowed to be buried as a Christian, and it wasn't just the people involved in the duel who got booted from the good graces of the church. Any lord or noble who allowed his citizens to duel was also excommunicated, along with anyone participating as a second, or anyone who was simply there to watch.

Play with fire, and you get burned

Papal Encyclicals Online says that 1139's Second Lateran Council was called by Pope Innocent II, and one of the things the 500+ attendees really, really hated was what they called the "most dreadful, devastating and malicious crime of incendiarism." In other words? Arson.

It was believed that arson was particularly bad because it so completely destroyed bodies and souls that were God's creation, and not only were arsonists excommunicated, but that excommunication couldn't be lifted with a simple apology. Instead, it required a year spent in either Spain or Jerusalem, doing service as penance.

It's also worth noting that belief explains some things that were happening around the same time... sort of. At the same time it was an excommunicable sin, it was also a popular execution method: presumably, because it destroyed every bit of a person. In the late 12th to mid-13th centuries, the Catholic Church got particularly fire-happy when they took aim at the Cathars, a religious sect with beliefs close to but not precisely the same as mainstream Catholicism. When burning individuals at the stake didn't allow them to burn enough Cathars, the Annals of Burns and Fire Disasters says they took to chucking them onto massive bonfires by the dozens.

Say Mary gave birth to Christ? Excommunicated!

Each and every Christmas, the same story is told: It's the one about Mary, Joseph, and a cranky innkeeper who made her give birth to Jesus surrounded by livestock. The story's been told a lot, but way back in 553, the Second Council of Constantinople decided (via Papal Encyclicals Online) that anyone suggesting the Virgin Mary actually gave birth like a normal woman was uttering a heresy that was worthy of excommunication.

The ancient text is a whole bunch of confusing, but it breaks down like this: basically, if anyone suggests that Mary gave birth to a man, that's grounds for anathema (which Wired says is a sort of excommunication for people who aren't technically part of the church). It was considered blasphemy and heresy, because it also denies — even by omission — the idea that Mary actually gave birth to God, or God the Word. Claiming anything else — or defending anyone who said or wrote otherwise — was a very good way to be shown the door.

Not venerating holy images

Christianity has a ton of saints, and a lot of them have incredibly dark stories... which one might expect, considering how many have body parts still floating around to be venerated. And that, says Papal Encyclicals Online, brings us to the Second Council of Nicaea of 787. They were trying to sort out whether or not the worship of images was a godly thing to do or if it was opening the door to Satan, and eventually decided that it depended on the "message." They came to the decision that every painting, mosaic, cross, instrument, vestment, image, or sculpture depicting Jesus, Mary, God, angels, saints, or holy men needed to be paid "the tribute of salutation and respectful veneration."

Failing to properly respect these images would result in an excommunication, and that was an idea that was reinforced in 869 by the Fourth Council of Constantinople. They were especially concerned with the treatment of the images of Mary and Jesus, and further stated that anyone who had already fallen afoul of church directives wasn't allowed to paint or create more images "until they are converted from their error and wickedness."

Living with a Jew or Muslim? Excommunicated!

The heart wants what the heart wants, and by 1179, the church had enough of that sort of sentimental poppycock. That's when the Third Lateran Council declared that any Christian living with a Jewish or Muslim person was immediately excommunicated. It was a strangely worded rule, too, stating that "Jews and Saracens are not allowed to have Christian servants in their houses," for pretty much any reason, because the character of a Christian who actually wanted to hang around with non-Christians was pretty suspect.

Now, fast forward a bit to 1215, and the Fourth Lateran Council, which Papal Encyclicals Online says established some rules for those who subscribed to other religions, too.

That included how non-Christians dressed, because they were tired of "a certain confusion" that arose when everyone looked "indistinguishable." Instead of taking that as a sign that hey, maybe we're all the same on the inside, they ruled non-Christians must, when appearing in public (on the days and occasions they were allowed to) "are to be distinguished in public from other people by the character of their dress," in order to stem the growing tendencies of "damnable mixing."

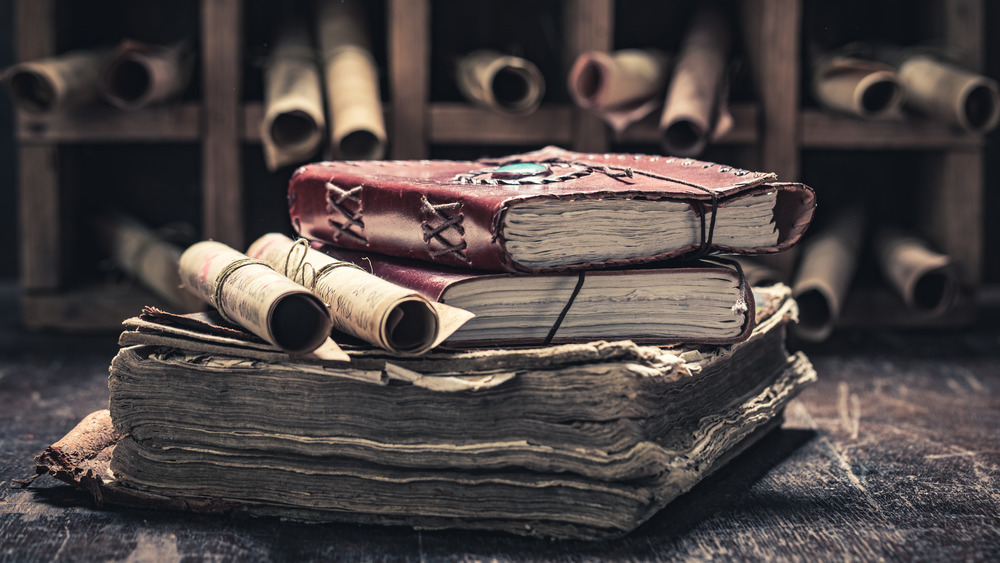

Printing a book, because books contained Bad Things

Some things never change, like that special sort of suspicion that comes with the invention of a new technology. When Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press in the 15th century, it's not an exaggeration to say that it changed the world. And the church? They were worried.

Papal Encyclicals Online says that the problems presented by the printing press were addressed at the Fifth Lateran Council, who decided that even though books could definitely be used "for the Glory of God," they could also be used as a tool for the other side, too. In order to stop that from happening, they ruled that any entity wanting to print any text would first have to send it to Rome, where it would be "closely examined" by a whole bunch of people, including vicars, bishops, and "the inquisitor of heresy" before permission was given to print it. Anyone who didn't submit their texts for church approval would be excommunicated and fined, while the church reserved the rights to seize and burn all copies of the book in question.

Giving Communion to a dog

Debates about whether or not something is an excommunicable offense haven't gone away. In 2013, the National Catholic Reporter told the story of an Australian priest named Greg Reynolds. He'd been excommunicated for a strange reason: the church claimed that he'd held a Mass, and that someone in attendance had taken a piece of the Eucharist — believed to be the body and blood of Christ — and given it to his dog.

Reynolds says that he only learned of it after the fact, and that no, he didn't actually give Holy Communion to a dog. He was still excommunicated for it, though, but that's not the end of the story.

When the diocese's Archbishop Denis Hart stepped in, he sided with the disgraced priest. Not only did he call the idea pretty insane, but he also said it was a cover-up for why he had actually been excommunicated: "because of his public teaching on the ordination of women contrary to the teaching of the church." Was the whole dog thing just an excuse to get rid of a troublesome priest?

Those times animals were excommunicated

Excommunication wasn't just for people, and while we might like to think that all dogs do, in fact, go to heaven, the church has been very, very strict with some animals. EP Evans wrote the incredibly terrible book The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals in 1906, says Wired. He found that there were a variety of animals excommunicated — and sometimes executed — for a variety of reasons, from as far back as 824, to as recently as the 1700s.

Pigs show up most often in the church's criminal record, mostly because of their tendency to eat anything — including Communion wafers and children, both of which are offenses that earned individual pigs the wrath of the church. Rats and insects — particularly locusts — show up a lot in the records of being slapped with anathema, particularly those swarms responsible for destroying crops.

But they're not the only ones: history is full of cases where horses, cattle, dogs, sheep, and even marine animals like eels and dolphins were excommunicated and executed for their crimes, many of which have been forgotten.

Excommunicating trees, because why not?

Details on this one are, sadly, a little scarce. It gets a mention in EP Evans' The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals, and it's a story preserved by a poet and lawyer named Barthélemy de Chasseneuz. While he doesn't give the dates this weird excommunication supposedly happened, the British Museum says Chasseneuz died in 1541 — so, before that. Whenever it happened, Evans says that Chasseneuz absolutely didn't question the validity of the tale at all, which says a lot about just how ordinary it seemed.

It started with a local French priest who found that instead of going to Mass, children were more interested in going to a nearby orchard and eating the fruit. The answer? The priest slapped the orchard with a form of excommunication called an anathema, and immediately, the trees stopped bearing fruit. That obviously wasn't great for the people who relied on the trees as a food source, and it was only with the intervention of the Duchess of Burgundy and a retraction from the priest that the trees started flowering again. True or not, it does make for a pretty great story.