What It Was Really Like Escaping On The Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad is considered the first movement of civil disobedience in the United States. This surreptitious network that began in 1790 would eventually contribute the fuel needed to ignite the Civil War, and the nation's trajectory thereafter, according to Fergus Bordewich's Bound for Canaan.

Most "fugitives" headed for Canada, as the Northern states provided little opportunity and safety to African Americans. Those who were able to tell their stories of escape were often documented by abolitionists, Northern newspapers, or their own memoirs. Some survived months alone in the wilderness, while others reached the North within days, per Fleeing for Freedom by George Hendrick. The severity of risk involved in the pursuit of freedom is merely a presentiment of what American life was like for African Americans less than 200 years ago, and what it was like to escape on the Underground Railroad.

Travel was usually at night, following the North Star

Transporting escaped slaves was a good way to immediately end up in jail, or hanged from the nearest tree, according to Ann Hagedown's Beyond the River. Conductors often began their journeys well into the night, with runaways buried beneath sacks of grain and other fake freight if going via carriage or wagon.

Some conductors, like a pretty prolific lady by the name of Harriet Tubman, led the way of the liberty lines on foot, per Catherine Clinton's Harriet Tubman: The Road to Freedom. Harriet Tubman often referred to the North Star when navigating runaways through the Southern wilderness. In one of her stories, two men had refused to cross a large river in the night, until they saw her jump in and swim to the other side. Harriet claimed, "I never ran my train off the track, and never lost a passenger."

But for many fugitive slaves, their journeys often went without any help from abolitionists along the way. And with many being illiterate, constellations were their only source of direction, according to Bound for Canaan by Fergus Bordewich. Charles Ball, for instance, was a slave who made a very rare escape out of a Georgia plantation and traveled on foot for nine months until reaching Maryland. His death-defying struggles were often on account of cloudy nights, and, understandably, having no clue of where he was actually going if he did happen upon an unfrequented road.

The safe houses, aka stations, weren't really safe

"Slave Stealers," as slave hunters called them, were under constant surveillance — which, in the 1800s, came in the form of rudely kicking down doors and searching every nook and cranny of the premises, per Levi Coffin's Reminiscences (via Fleeing for Freedom). Free African Americans were in exponentially more danger for housing fugitive slaves and often couldn't take them in, at least not for long. So it was difficult for slaves who didn't have white connections, and they often went without help. Runaways who stayed at stations also couldn't be seen by any children at the risk of their oblivious blabber and were hidden in trick closets and lofts for their entire stay, according to Dawn of Day: Stories from the Underground Railroad.

Some stations of white abolitionists, like Levi Coffin's, were able to house runaways for longer periods. From his own journaled accounts, Reminiscences, Coffin was well-to-do from his business endeavors of manufacturing flaxseed oil and was able to not only host groups of runaways for weeks or months at a time but to establish multiple teams of conductors to constantly keep slaves in the line of safety of the Underground Railroad. Unlike Coffin — who, by his own admission, received threats that always turned up empty on account of his socioeconomic status, other white abolitionists were punished severely.

Runaways often approached their escape as a matter of freedom or death

William Still, a free man who became a pivotal member of the Underground Railroad, kept records of many fellow liberated slaves in The Underground Rail Road (via Fleeing for Freedom). In one account, he received a group who said they had been confronted by headhunters on their way out of Maryland on Christmas Eve. A mob of white men rode up to their quiet convoy and, to the ruffians' dissatisfaction, were promptly greeted with cocked pistols and Bowie knives. Seeing that the fugitives were ready to die in this standoff rather than be returned to their owner's frosted fields, the assailants stepped to the side and let their carriage pass.

Per Levi Coffin's Reminiscences, Margaret Garner killed her her nine-month-old daughter and attempted to kill herself when she was caught by slave hunters. The mother of four had been previously foreboding that neither she, nor her children, would live as slaves. A few years after Margaret was returned to her owner, she jumped off a ferry with one of her children in her arms. She was caught, but her child drowned. Margaret never attempted escape again.

Success sometimes came with a good old-fashioned disguise

According to William Still's The Underground Rail Road, Ellen and William Craft were able to make a rare escape from Georgia in costume. Ellen's skin was fair enough to be mistaken as white, while her husband's was not. So they decided to make Ellen a young, tan, traveling planter with William as her slave. Ellen, however, lacked the fashionable whiskers of the time and wasn't able to use a legitimate name to register them at lodges to stay at along the way. But such problems became mere opportunities for further character development, with the addition of an arm sling for her writing hand and a face covering for a terrible toothache. Surprisingly, a white invalid being escorted by their slave wasn't really out of the norm! They stayed at multiple ritzy hotels and actually boarded a train that delivered them to freedom in Philadelphia.

Another account Still recorded was from Clarissa Davis, a young woman who fled Virginia in May 1854 with her two brothers but was left behind to wait at a station near Richmond. She stayed secluded in a lightless coop for two and half months before getting the opportunity to board a steamship to Philadelphia. The night before, she prayed for rain to keep the police, who would easily notice her, off the streets and was much obliged with a nasty squall. The next morning, she waltzed onto the ship in men's clothing.

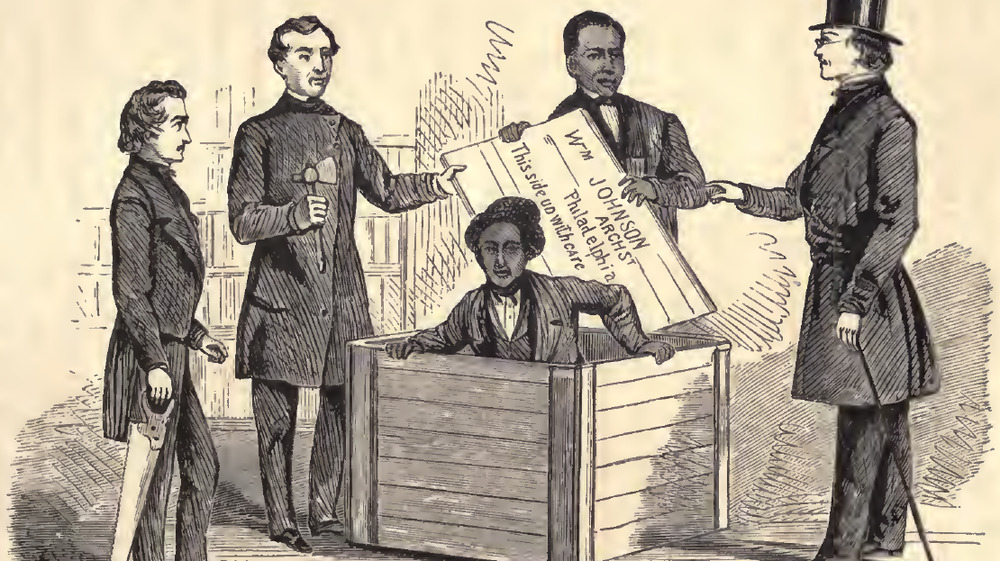

Becoming cargo was a viable option

It was not uncommon for slaves to be separated from their spouses and children for trades, which is what happened to Henry "Box" Brown, per William Still. After losing his wife and children when his owner sold them in 1849, Brown stuffed his 200-pound self into a small wooden crate, and with the help of a white abolitionist, the box was nailed shut with a few discreet air holes. The man who helped pack Brown had previously been imprisoned for shipping slaves off from plantations and even survived a brutal assassination attempt for these actions that left five stab wounds in his chest. But his convictions were evidently solid, as he shipped the precious package 350 miles from the tobacco plantation on which Brown worked in Richmond, Virginia, to another white man's home Philadelphia.

According to Kathryn Schulz in The New Yorker, during shipment, Brown was loaded first onto a horse cart, then a train, and then a steamship, where passengers turned his box up on its side to use as a seat. After arriving in Washington, D.C. and being transferred on and off of a few other carts and wagons, the crate made it inside the doors of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee. Henry Brown was received by an abolitionist known as James McKim and a few others, whom he casually asked, "How do you do, gentlemen?" before promptly passing out. He quickly became an avid voice in the Underground Railroad movement.

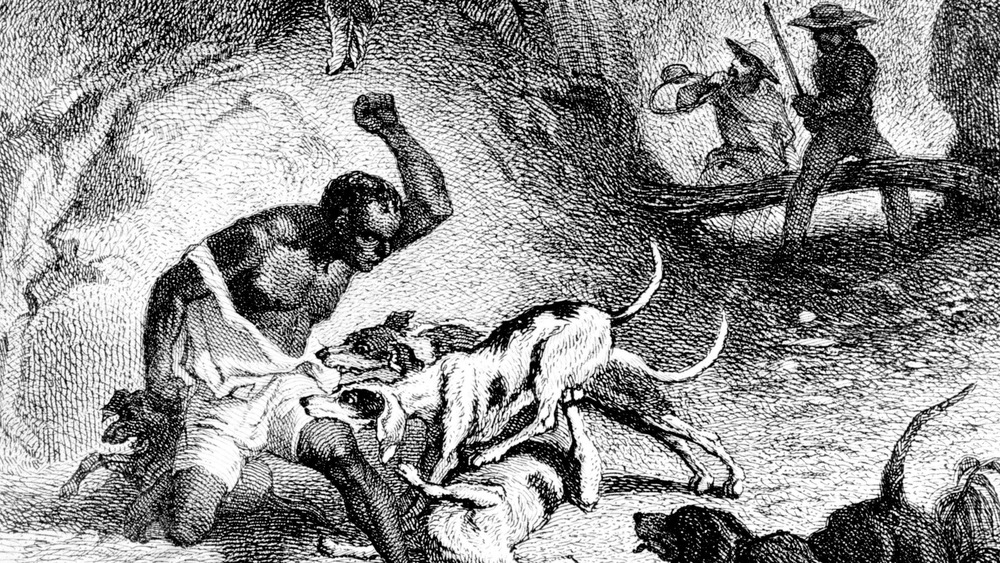

Many were chased and caught by bloodhounds

Using dogs to hunt for slaves was considered a sport by lynch mobs, according to Encyclopedia of the Underground Railroad. Slaves often left all of their possessions behind when they ran away, making it easier for slave hunters to give the dogs a fresh scent to follow. Bloodhounds were known to violently attack slaves once they were found, and hunters would often wait to restrain them until the runaways were severely battered.

Henry Bibb escaped with his wife and daughter through the swamps of Louisiana, and the three were followed by hounds for several days, according to his memoirs. Families moved slowly through the dense, wet, wildlife-filled forests of the Deep South. One night, as they camped on a small island between rivers, they were awakened by howling, but from a pack of wolves surrounding them. Bibb charged them with his Bowie knife, and somehow, that did the job.

Within the next couple days, the bloodhounds finally closed in on them. From his memoir, Bibb recounts, "I started to run with my little daughter in arms [...] But we soon found that it was no use for us to run. The dogs were soon at our heels, and we were compelled to stop, or be torn to pieces by them." They were caught, returned, and sold apart as punishment. Bibb was never able to reconnect with his family again.

Rarely did family and freedom go together

Traveling on the Underground Railroad was risky as one slave, let alone in groups. While some managed to do it without being caught, many were found. This meant many people had to leave their loved ones behind to avoid being caught. Harriet Tubman made multiple trips to retrieve various family members, rather than bringing them back as a group, which most likely contributed to their success, according to author Catherine Clinton.

According to Levi Coffin's Reminiscences, a slave by the name of Jim escaped from Kentucky and made it all the way to Canada on his first try. But he was pretty overwhelmed with guilt after leaving his wife and three children behind and had some substantial cajones to go back for them. When he returned to his owner, he apologized and told him how freedom really wasn't all that great. Jim also threw in how he really missed working for him. Without considering if Jim was perhaps fibbing, even a little bit, his owner was delighted and welcomed him back to the farm with open arms. Jim worked through the fall and winter and miraculously took a group of 14 other slaves (his family included) with him back to Canada.

The Ohio River was a common route on the way to freedom

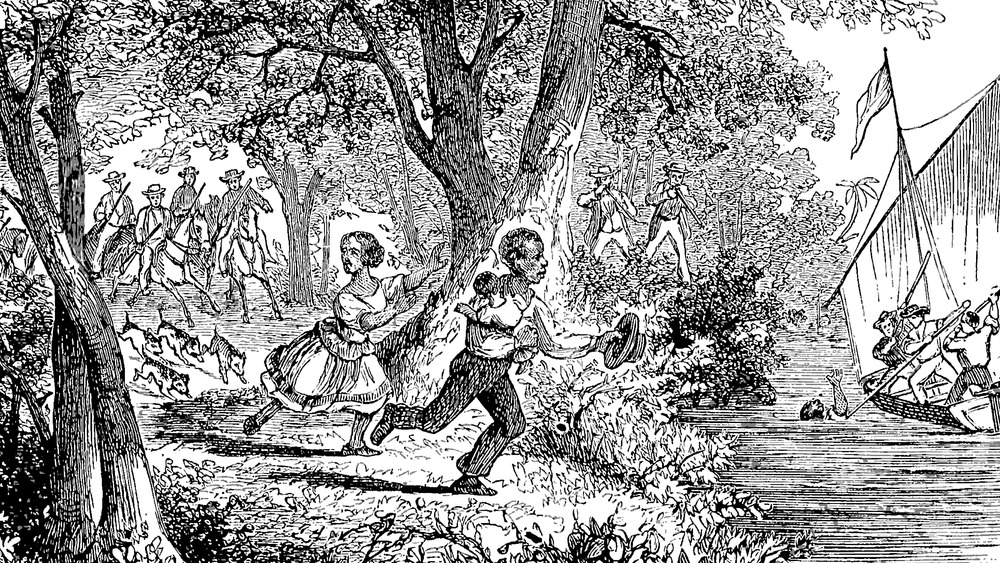

Ohio technically prohibited slavery. By 1841, it also came with the advantage of making any runaway immediately free, according to Greg Hand, writing for Cincinnati Magazine. Since the Ohio River acts as the literal border to Kentucky and Virginia (now West Virginia), the imposing waterway most likely saw thousands of slaves swim, row, and occasionally walk across it.

The incredible escape of Eliza Harris is considered so legendary that when it was told to author Harriet Beecher Stowe, she immortalized the genuine event in her best-selling novel, Uncle Tom's Cabin, according to Fleeing for Freedom. On a winter night, Eliza ran through a frosted wilderness with her two-year-old son in her arms and a group of slave hunters following right behind her. When she reached the riverbank, she bounded onto the frozen patches of the Ohio, leaping from iceberg to iceberg as each of them fractured beneath her bare feet.

Her owner frantically scoured the water's edge for a boat as she met an insecure state of liberty on the other side. Harris was lucky to shortly happen upon the unattended and unlocked cabin of Reverend John Rankin. The famous abolitionist said she made a fire, hung up her clothes to dry, and went to bed with her son. They were found in the morning and delivered to Rankin's home to properly secure their freedom thereafter.

Success was often dependent on place, looks, and luck

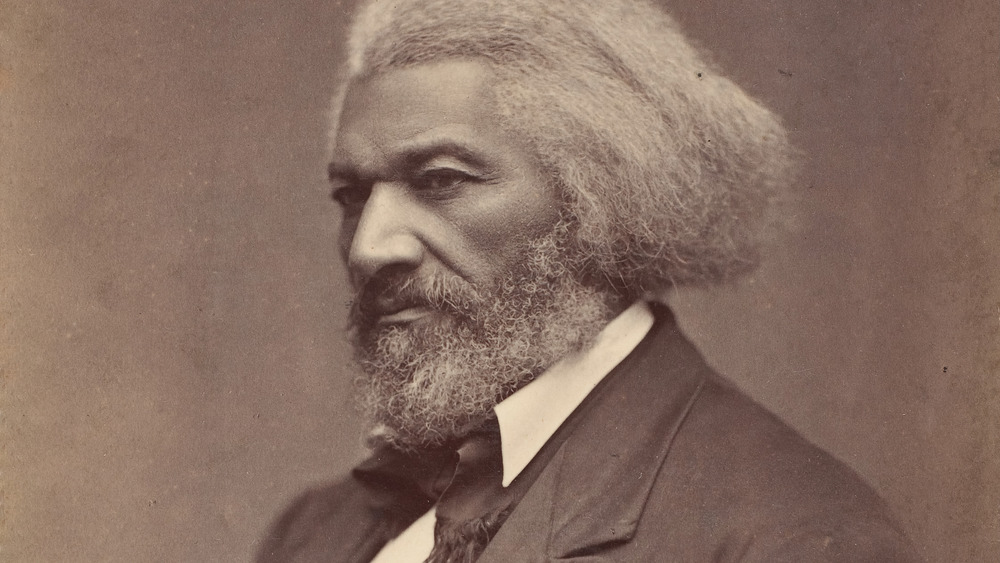

Per Fergus Bordewich, most slaves who achieved freedom were from Kentucky, Virginia (now West Virginia), and Maryland. Some were able to pass themselves off as free with forged "Certificates of Freedom,” which were given to freed slaves in the North who traveled often or worked along the major rivers of the Midwest. They included a description of the slaves' appearance, including their scars, skin tone, and hair texture. For Frederick Douglass, he was able to pass himself off as a sailor with the help of borrowed papers and the ability to talk shop, according to History.com. He did have one close call when he was asked to show his papers by a railroad conductor. This shouldn't have been a problem, except Douglass looked nothing like the description. The conductor evidently found the official bald eagle emblem stamped at the top to be sufficient and barely gave the document a glance.

According to Encyclopedia of Alabama, others were able to pass themselves off as Native Americans or even white. But these tactics frequently proved to be unsuccessful in the face of even the slightest tinge of skepticism from ruffians. Those who were caught on their trek to Canada were often sold into the Deep Southern states as punishment, which essentially ensured they would never make it out again. And because many runaways who never became acquainted with members of the Underground Railroad suffered from starvation, some decided to return to slavery on their own.

Finding allies or imposters was a toss-up

Unless slaves traveled from station to station on the Underground Railroad, finding people to help along the way was as good as Russian Roulette. Many people weren't officially "conductors" or "agents" of the Underground Railroad but were sympathetic and were a major part of liberating slaves. Josiah Henson and his family were transported across Lake Erie by a ship captain who arranged to pick them up in the night shortly after meeting them, per Jacqueline Tobin.

Henry Bibb had a mixed bag of interactions during his multiple escapes and finally was betrayed in Cincinnati by a group of white men who posed as friends ready to aid his endeavors, according to his autobiography. In fact, they were paid slave hunters who were tipped off by two Black men Bibb had met earlier in Cincinnati. Bibb recalled, "They undertook to justify the act by saying if they had not betrayed me, that somebody else would, and if I would tell them where they could catch a number of other runaway slaves, they would pay for me and set me free, and would then take me in as one of the Club." He declined the proposition and later became a pivotal contributor of the Underground Railroad.

On Frederick Douglass' first attempt to escape, he organized a plan with six other slaves. One of them became too fearful and spilled the beans to their master. Douglass, of course, made it out on his own two years later.

The Fugitive Slave Act really screwed things up

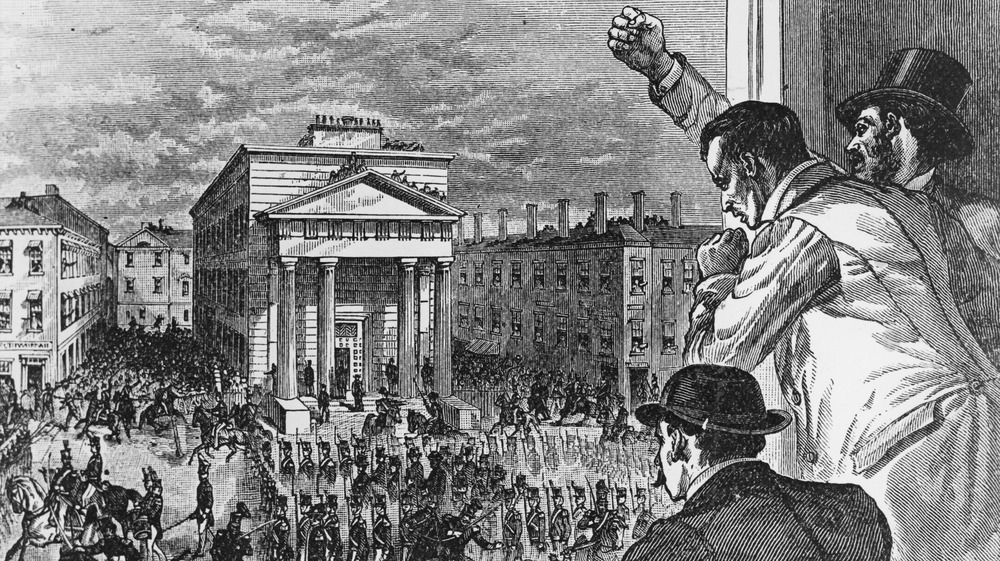

As slaves began to escape more often with increasing success, the South began throwing around the idea of breaking away from the Union, according to James C. Cobb, via Time. So as a compromise, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, a law that allowed slave owners to kidnap and return runaways in the North and also avoid fair trials for African Americans in free states.

Slave hunting became quite the business, with rewards over $1,000 (over $33,000 today) for captured runaways, per Still. However, this trafficking business quickly became another source for slave trading, as long-term free citizens were abducted and sold back into slavery on bogus charges, according to Bound for Canaan. Black communities like Christiana, Pennsylvania, were especially terrorized by slave hunters and eventually rioted against a group of ruffians in a skirmish that left one dead and plenty injured.

David Ruggles, for example, was a free man who helped establish the Underground Railroad in New York and was responsible for thousands of fugitives who made it safely to Canada. He himself has accounts from The Liberator newspaper of free men being arrested, chained, and dragged through the streets "like a beast to the shambles." But due to his loud and proud involvement in the Underground Railroad, he became a hot target and was nearly kidnapped and sent to the South himself.

Achieving freedom came with a whole other basket of hardships

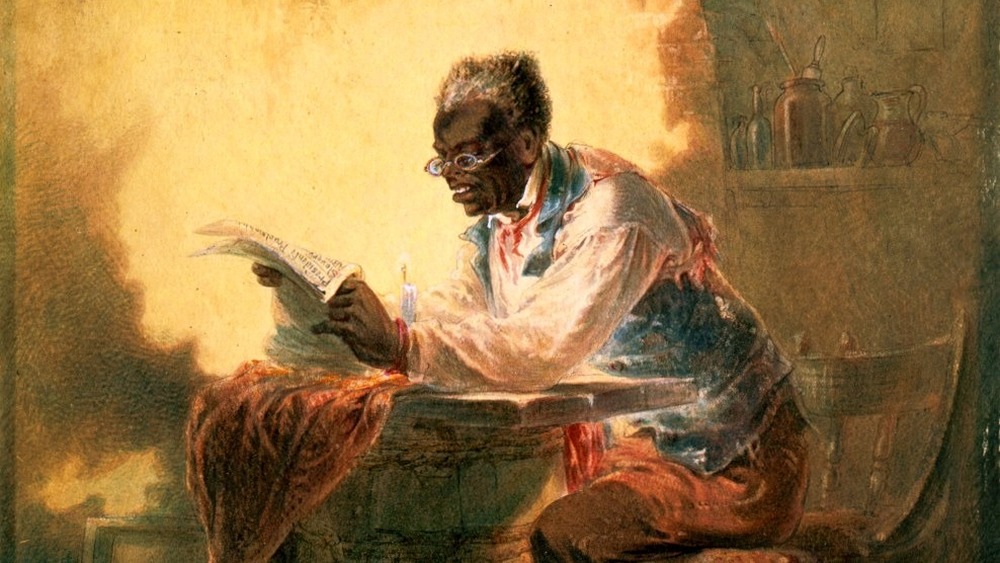

Newly freed slaves were often at the mercy of educated abolitionists in the North. In the 1830s, anti-literacy laws began to develop throughout the South as abolitionists began to circulate anti-slavery texts and newspapers, per Collette Coleman, via History.com. Most free slaves had to learn to read and write, use money, and generally become accustomed to sovereignty. Harriet Tubman herself never learned to read and told her memoirs to literate friends and family members, per Catherine Clinton.

As more freed slaves were making it to Canada, white abolitionists and previously enslaved activists opened schools, per Fergus Bordewich. Some learning spaces, like reading rooms that were established for Black men in New York (because they weren't allowed in libraries), were deemed illegal for whatever bologna reason and had to be done in secret.

Other organizations like the Fugitive Union Society were established to empower the freed slaves to own land and participate in education, per Jacqueline Tobin. However, African Americans soon became blocked from land ownership throughout the North, and housing became a major issue for many freed slaves. Henry Bibb, a freed man who became well-educated and highly involved with the Underground Railroad in New York and Canada, organized various conventions to create solutions to the various problems African Americans faced in the North. He stated that "the eye of the civilized world is looking down upon us to see whether we can take care of ourselves or not."