The True Story Behind The 1925 Nome Serum Run

Nearly a century ago, the discovery of a deadly and highly contagious disease in a remote Alaskan town sparked a heroic effort to deliver an antidote. Twenty teams of sled dogs raced across the frozen landscape, through whiteout blizzards, to transport the serum across land wrought largely inaccessible by harsh winter conditions. This great human and canine achievement came to be known as the Nome serum run or the Great Race of Mercy.

But today, most of the story has been forgotten, simplified in the media and movies that only focus on a handful of participants. For example, you may have heard of Balto, but do you know Leonhard Seppala? The true story behind the 1925 Nome serum run is even more daring and more impressive, including a 670-mile relay, a near miss, a potentially deadly shortcut, and the trusting relationship between sled dogs and their mushers.

The plan to save Nome

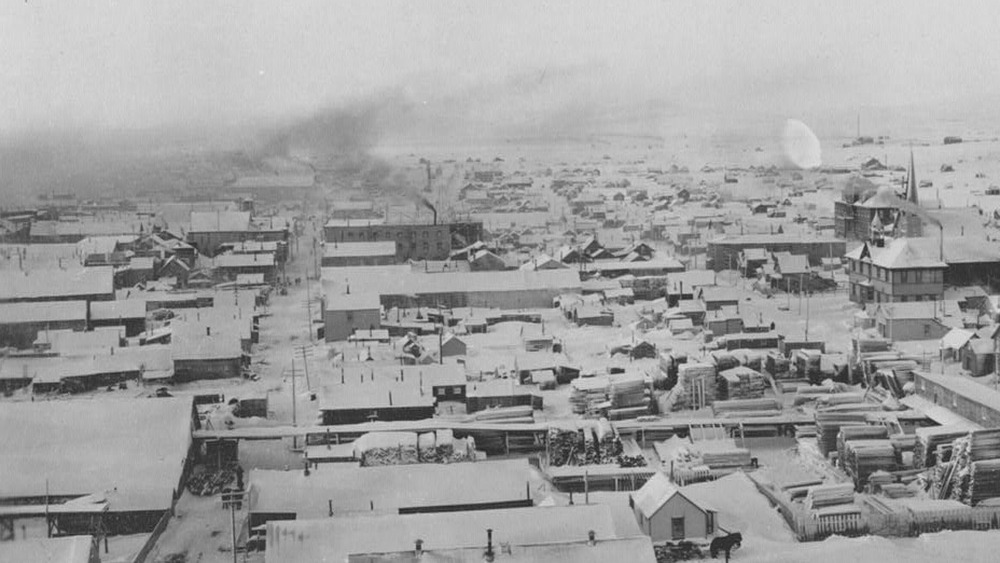

In January 1925, the tiny village of Nome in west Alaska was home to fewer than 1,500 people, including Indigenous Alaskans and European immigrants. That month, there was an outbreak of diphtheria, a disease that spreads through respiratory droplets and creates a deadly toxin. Diphtheria is especially contagious and dangerous among young children — several children had died before Nome's government realized they had an epidemic on their hands.

Nome's supply of the serum needed to treat diphtheria had expired the previous summer. The town's doctor, Dr. Curtis Welch, had ordered more, but the port froze over before the medicine arrived. In the midst of winter, Nome was inaccessible by ship, plane, or train. Nome was put into quarantine, but there were still 20 confirmed diphtheria cases and 50 more suspected. Without the serum, anyone who caught the disease would most likely die.

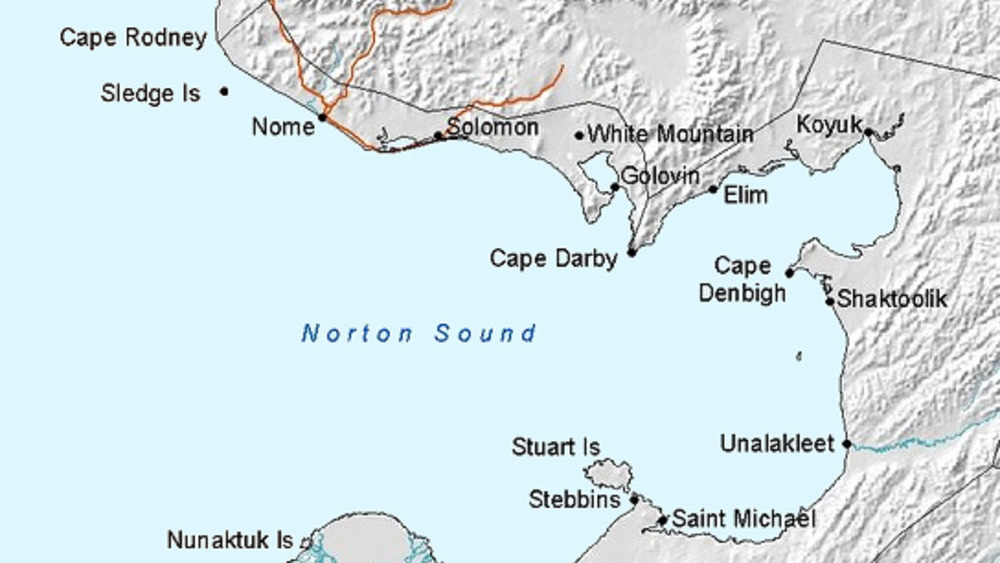

A callout for antitoxin located a supply 1,000 miles away in Anchorage. Local officials decided that the serum would travel by train to Nenana, where one dog sled team would pick it up and take it to Nulato, where they would hand it over to another team, who would take it back to Nome, a total distance of 674 miles.

Typically the route from Nenana to Nome took dog sled teams working for the postal service an average of 25 days, according to the BBC. The record was nine days. But in the extreme cold, the serum would last only six.

The plan to save Nome changes — too late

The musher charged with traveling the Nome to Nulato route was Leonhard Seppala, a Norwegian-born former gold miner, ski champion, and three-time winner of the All Alaska Sweepstakes. As Sports Illustrated explains, the sweepstakes was a grueling sled dog race that spanned more than 400 miles along the Bering Sea, covering much of the same ground as the Nome serum run. By 1925 — eight years after winning their third title — Seppala and his lead dog Togo were Alaska's most famous sled dog team. At one point, it was suggested that he go all the way to Nenana and back.

Instead, on January 27, Seppala set off for Nulato. But after he'd left, Alaska's governor Scott C. Bone changed the plan. Instead of two mushers meeting in Nulato, the serum would travel by dog sled relay, with teams waiting at different roadhouses to pick it up and run their stretch. His theory was that dividing the distance between multiple teams would ensure the dogs and the mushers would be fresher and faster.

Unbeknownst to Seppala, he was now scheduled to pick up the serum in Shaktoolik, about 95 miles to the west of Nulato. Unfortunately, since he'd already left, there was no way to tell him about this change, especially since his route didn't go through any villages with telephones. The organizers had to hope that their star musher didn't miss the serum altogether, which could potentially have jeopardized the whole attempt.

It took 20 mushers to move the serum from Nenana to Nome

When Gov. Scott C. Bone decided to add more mushers to the plan, he sent out a message looking for experienced dog sled teams who lived along the route and were willing to volunteer for the dangerous mission. According to Sports Illustrated, the 20 mushers who signed on included other sweepstakes racers, mailmen, trappers, and guides, all of whom had experience on the trails. They came from different backgrounds, including Indigenous Alaskans and Norwegian immigrants.

The names of many of these mushers have been lost to history, partly thanks to one particular musher who proved to be the best at PR and partly thanks to lazy media coverage. But that's for later. There were probably as many motivations as there were men, but in 1995, on the 70th anniversary of the serum run, the last surviving musher, Edgar Nollner, gave a rare interview to AP News about his role. Asked why he took part in the mission, Nollner said, "I just wanted to help, that's all."

Over 150 sled dogs took part in the serum run

In addition to the 20 mushers, 150 dogs dragged the serum along its treacherous route. They were made up of two breeds, Alaskan Malamutes and Siberian Huskies.

Alaskan Malamutes had long been the favorite of European settlers/invaders in Alaska. But their dominance was threatened in 1909. Fur trader William Goosak had noticed that the Chukchi people who lived by the Bering Sea in modern-day Russia used a smaller breed, Siberian Huskies. The BBC described Siberian Huskies as "the Goldilocks of racing sled dogs." They were big enough to pull heavy loads, small enough that they wouldn't overheat (unlike Malamutes), had a long stride, and always kept one paw touching the snow — essential for preventing the sled from slipping backwards with every step.

The Siberian Huskies also had certain adaptations that made them freakishly good at dealing with cold weather. For example, they have a special layer of hair that traps warm air against their bodies — and they don't shed in winter — and giant fluffy tails that they use as blankets when they're sleeping.

Goosak caused an upset when his Huskies finished third in the 1909 All Alaska Sweepstakes. The following year, Iron Man Johnson and his Huskies set a still-unbeaten record for the 408-mile course, of 74 hours and 14 minutes. But it was Leonhard Seppala's consecutive victories in 1915, 1916, and 1917 that proved the upstart Huskies had the superior speed and cold weather endurance dog sledding required.

The mushers slogged through harsh Alaskan weather

The mushers understood the risks of the Alaskan winter — but the weather during the run was particularly brutal.

The musher who collected the serum from the train was "Wild Bill" Shannon and his team of Malamutes. With temperatures hitting as low as -62 degrees Fahrenheit, Shannon had to run alongside the sled to keep warm, but he still suffered hypothermia and frostbite on his face, and three of his dogs died. After a four-hour break in Minto, Shannon left the fire to brave the below-freezing conditions again and finished the rest of his 52-mile leg to Tolovana.

As the run proceeded, the weather grew increasingly dangerous. Edgar Nollner picked up the serum at Whiskey Creek and handed it to his brother George 24 miles away in Galena. He recalled that he couldn't even see his dogs in front of him because of the fog rolling off the snow. "I just let them go and they followed the trail," he told AP News.

On the third day, another musher, Charlie Evans (who was Nollner's brother-in-law) lost his two lead dogs when the team tried to cross a river and the ice started to crack, soaking the animals. According to The New York Times, Evans picked up the harness and led the team for the rest of his stint, arriving in Nulato with the serum and the bodies of the dogs in the sled.

Leonhard Seppala braved the treacherous Norton Sound — twice

While the mushers battled their way through their respective legs of the relay, Leonhard Seppala and his team of Siberian Huskies were still heading for Nulato. On the afternoon of January 31, musher Myles Gonangnan delivered the serum to Shaktoolik, where Seppala was supposed to pick it up under the new plan. Another musher, Henry Ivanoff, was waiting in case Seppala hadn't heard about the change.

Meanwhile, Seppala was actually quite close by. As Sports Illustrated reports, he'd crossed the Norton Sound, a 42-mile stretch of frozen sea that served as a shortcut but was also extremely dangerous. It was so dangerous, especially in stormy conditions, that Gonangnan had gone around it. Thanks to the shortcut, Seppala reached Shaktoolik just as Ivanoff was leaving.

Not expecting to see the other musher, Seppala nearly passed him. Ivanoff — who was untangling his dogs after they had been spooked by a reindeer — saw Seppala and shouted, "The serum! The serum! I have it here!" Luckily the wind carried his words to the other musher.

By this point, Seppala and his dogs had already traveled 170 miles from Nome, and they now faced a 91-mile trek to Golovin. Without stopping to rest, Seppala turned the team around and prepared to recross the sound as a violent storm was moving in. Fortunately, the musher had a secret weapon — his 12-year-old lead dog, Togo.

Togo was famous in the sled dog world

Of the 150 dogs that pounded their way across ice and snow in blistering cold and searing winds during the Nome serum run, Leonhard Seppala's lead dog Togo deserves a special mention.

Seppala initially dismissed Togo, who was born undersized and sickly. But on Togo's first run — a staggering 75 miles — Seppala realized that he was a natural lead dog. Lead dogs are like sled dog quarterbacks — they determine the route the team will run, testing whether the terrain will hold, and navigating around potential obstacles. By 1925, 12-year-old Togo was the most famous lead dog in Alaska.

As Sports Illustrated reports, Togo and Seppala had experience with the Norton Sound. During a previous crossing, their team had got stuck on an ice floe, sending them towards the open sea. Seppala tied a rope around Togo and threw him onto the main section of ice, so the dog could pull the rest of the team to safety. The rope snapped and fell in the freezing water — and Togo jumped in after it, got back onto the land, and pulled the rest of his team over.

This time, Seppala, Togo, and their team were facing winds that brought the temperature down to -85 degrees and threatened to crack the ice again. In whiteout conditions and total darkness, Seppala relied on Togo to navigate the team across the ice safely.

The serum crosses the finish line

After crossing the Norton Sound, Leonhard Seppala and his team rested a few hours before traveling the rest of the way to Golovin, where Seppala handed the serum to Charlie Olson. Olson was blown off the trail and sustained frostbite in temperatures of -70 degrees, but he made it to Bluff and handed the serum to penultimate musher Gunnar Kaasen.

Kaasen worked for Seppala and had chosen Siberian Husky Balto — whom Seppala didn't rate — as one of his two lead dogs, alongside another named Fox, according to Sports Illustrated. Kaasen tried to wait out the storm, but when he realized it wasn't going to subside, he set out into it.

In one especially dangerous moment, an 80 mph gust of wind smashed into the sled, sending the serum — which had been encased in a tube and wrapped in furs — into the snow. Knowing that the serum would be ruined if it got too cold, Kaasen took off his glove and plunged his hand in after it. He rescued the serum but suffered severe frostbite.

Despite the conditions, Kaasen completed his 28-mile leg early — then kept going for another 25 miles, instead of waking up the next musher. He arrived in Nome at 5:30 a.m. on February 2. All together, 20 mushers and their dogs had traveled 674 miles in 127 hours and 30 minutes, half a day faster than expected.

What happened to the town and the mushers?

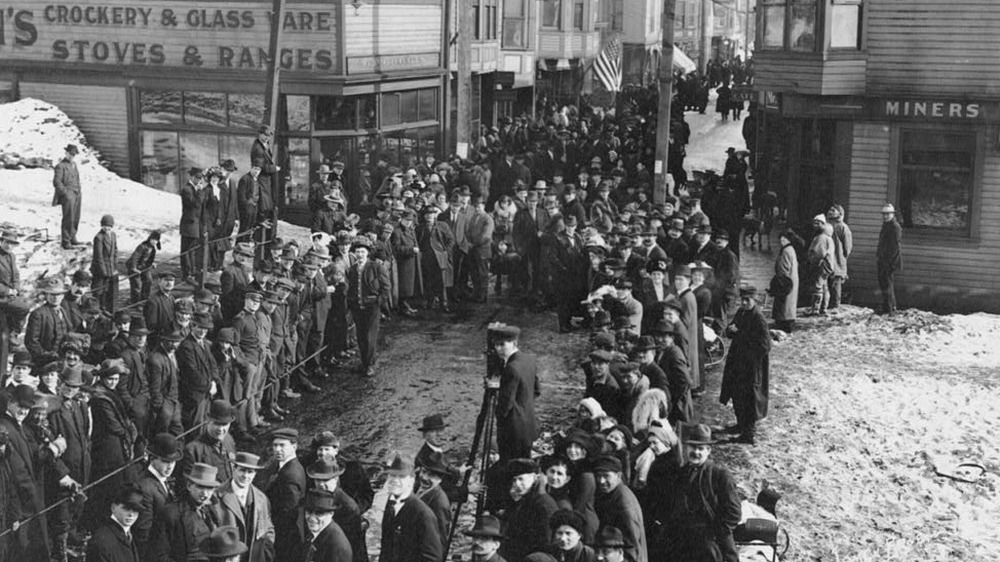

Almost inevitably, the 300,000 units of serum had frozen. But once it thawed, Dr. Curtis Welch was able to treat his diphtheria patients. More people had fallen sick while the race was ongoing, only increasing the town's need. On February 21, three weeks after Gunnar Kaasen arrived with the serum, the quarantine was lifted and the threat of epidemic was officially over.

While the mushers had been racing through the wilderness of Alaska, Nome's plight and the heroic effort to save the town had caught the attention of the media. So when Kaasen rode into town, frostbitten and exhausted, he instantly became the face of the whole effort. The other mushers were miles away, and after finishing their respective legs, they simply went home. According to AP News, the Alaskan government gave them each $35 (other sources say $25), and the serum makers sent out medals (other sources say it was President Calvin Coolidge). Happy with a less complicated story, the press didn't bother to track them down.

As incredible as the feats of all of the dog sled teams were, some saw it as just another day at the office. The New York Times reported that the last surviving musher, Edgar Nollner, died in January 1999 at the age of 94. During an interview with AP News four years earlier, he said of the run — "I don't think about it much — just when people call me about it."

Balto and Gunnar Kaasen became famous — at a price

Gunnar Kaasen did share the credit with one other participant. According to Sports Illustrated, he told reporters that Balto had led the way when the musher was blinded by the storm. Kaasen and Balto became celebrities and even went to Hollywood — where Balto had his own hotel suite — to star in a movie, Balto's Race to Nome, released in June 1925. A statue of Balto was unveiled in New York's Central Park on Dec. 15, 1925, in front of the real Balto, who was on a victory tour with Kaasen and six other dogs. They also toured the vaudeville circuit.

Sadly, when Kaasen had to return to Nome, he couldn't afford to take the dogs with him. He left them with the vaudeville promoter, who sold them to a cheap museum.

One visitor, George Kimble, was appalled to see the dogs living out their days so miserably. He convinced the museum's owner to sell them to him for $2,000 — on the condition that he could raise the money in two weeks. With help from the Western Reserve Kennel Club, radio appeals, and fundraising efforts by schools, hotels, factories, and stores in his native Cleveland, Kimble raised the money. In March 1927, the seven dogs were moved to what is now the Cleveland Metroparks Zoo. Balto died aged 14 six years later — he was stuffed and his body is still owned by the zoo.

Leonhard Seppala was furious that Togo didn't get proper credit

Leonhard Seppala — who had traveled nearly twice the distance of any of the mushers and over some of the most dangerous terrain — grew resentful of the spotlight Gunnar Kaasen was shining on himself and Balto. He had bred and trained Balto and didn't think he was worth the fuss. According to the Anchorage Daily News, in a 1927 interview, he disputed reports that Balto had led the team alone, and said that Fox deserved joint credit.

Mostly, Seppala thought it was unfair that Togo didn't get due respect. After calling Kaasen back to Nome, he took Togo on their own victory tour. They traveled around the country, met explorer Roald Amundsen, released a book, and starred in an ad campaign for Lucky Strike. In 1930, Seppala published his memoir, Seppala: Alaskan Dog Driver.

The end of the tour took them to Poland Spring, Maine, where Seppala co-founded a kennel breeding Siberian Huskies. When Seppala returned to Nome, he left Togo in Maine. Togo's health started failing two years later, and Seppala had him put to sleep on Dec. 5, 1929, aged 16. Like Balto, Togo was stuffed and is now on display in the headquarters of the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race. Seppala lived to be 89 and is still a mushing legend. Every year vets working for the Iditarod race give the Leonhard Seppala Humanitarian Award to the musher who takes the best care of their dogs.

Two movies give different accounts of the Nome serum run

If you've heard of the Nome serum run and aren't an expert on Alaskan or mushing history, chances are it's because of at least one of two movies.

The first, Balto, was an animated feature released in 1995 that portrayed Balto as a half-wolf/half-husky underdog who becomes the unlikely lead of a single dog sled team charged with collecting and delivering the serum. The movie involves a fight with a bear (which would probably be hibernating during January), a sprint through a cracking ice cave, and Balto carrying a sled loaded with the serum and his musher up the sheer side of a cliff. It's undoubtedly an adorable movie, especially for young dog lovers, but if you've read the rest of this article, you already know how wildly inaccurate it is.

The more recent onscreen version of the Nome serum run came in live-action movie Togo, starring Willem Dafoe as Leonhard Seppala. In many ways this movie is surprisingly accurate. (If you don't want to learn spoilers, stop reading now.) According to Slate, many of the scenes showing Togo as a mischievous but determined puppy really happened — including the jump through the window to get back to Seppala. The ending is Hollywoodized — no mention of Maine or Lucky Strike — but with Balto and Gunnar Kaasen claiming so much attention, it's good to see that every dog really does have his day.