Historical Events From "We Didn't Start The Fire" You Don't Know Anything About

When was the last time you actually thought about the lyrics to "We Didn't Start The Fire?" Take a listen and see if you recognize all of the historical events that it lists. In Billy Joel's iconic song, he lists over 100 famous events and people starting in the year 1949, the year that Joel was born, and ending in 1989, the year that the song was released.

While the song isn't an exhaustive list of historical events, it shed a light on what was being talked about in the media at the time. And many of the events ended up having lasting impact that can be felt over half a century later. However, although all of the events mentioned in the song were once headline stories, some of them have faded from public memory.

Here are some historical events from "We Didn't Start The Fire" you don't know anything about.

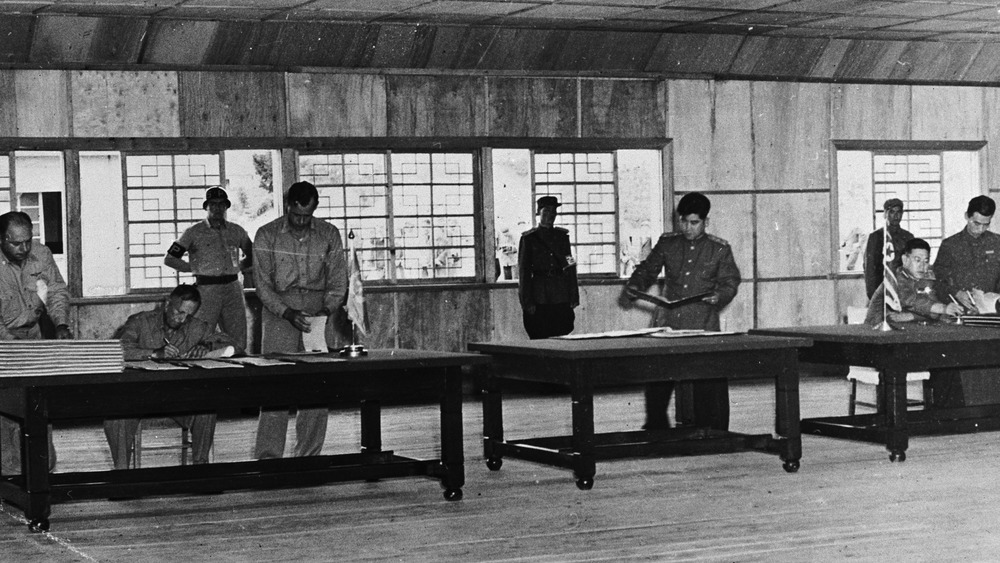

Panmunjom: An empty village

Before 1951, the village of Panmunjom, also written Panmunjeom, was known as the village of Neolmun-ri. KBS reports that when talks for the armistice during the Korean War were proposed, Neolmun-ri, "known for its tavern" was suggested as a location. The village name was rewritten in Chinese characters so Chinese officials could find the location, and so "Neolmun-ri tavern village" was translated to "Panmunjom, with pan, mun, and jom meaning 'wooden board,' 'door,' and 'tavern,' respectively."

According to The Korea Times, the talks went on for two years, and finally in 1953, "both sides agreed to put hostilities on hold indefinitely," although the war never technically ended. As a result, the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) was created as a place where neither North nor South Korea have jurisdiction, and Panmunjom became the official spot where officials from both sides would meet, writes The Straits Times.

The village itself is also divided into north and south, although people used to cross over the demarcation line relatively frequently. But after an ax murder in 1976, the Bridge of No Return, often used for border crossings, was closed, and the concrete slab was installed as a dividing line. The New York Times reports that as of 2019, Panmunjom is "uninhabited by civilians."

Lebanon: The first of many interventions

When the United States invaded Lebanon in 1958, few would've guessed that it would become the first in a long list of military interventions in the Middle East. Al Jazeera reports that this was "the first overt US military intervention in the region," and after landing on Khalde beach on July 15, 1958, within four days there were 14,000 U.S. troops in Beirut.

Brookings writes that although American troops "had been in the Middle East since World War II," they weren't there for combat purposes. But in 1958, President Camille Chamoun of Lebanon reportedly requested U.S. intervention in order to suppress "civil strife actively fomented by Soviet and Cairo broadcasts."

It was this justification of protecting the world from Soviet invasion and "another world war" that President Dwight D. Eisenhower sold to the United States. Meanwhile, he "made no mention of the fact that Chamoun was illegally seeking a second term and even claimed Chamoun did not seek reelection." This policy of giving economic and military aid to countries in the Middle East that were resisting "overt armed aggression from any nation controlled by International Communism" became known as the Eisenhower Doctrine.

And in "Contesting Arabism," Salim Yaqub writes that the Eisenhower doctrine "also sought to 'contain' the radical Arab nationalism of Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser and to discredit his policy of 'positive neutrality,' or nonalignment in the Cold War."

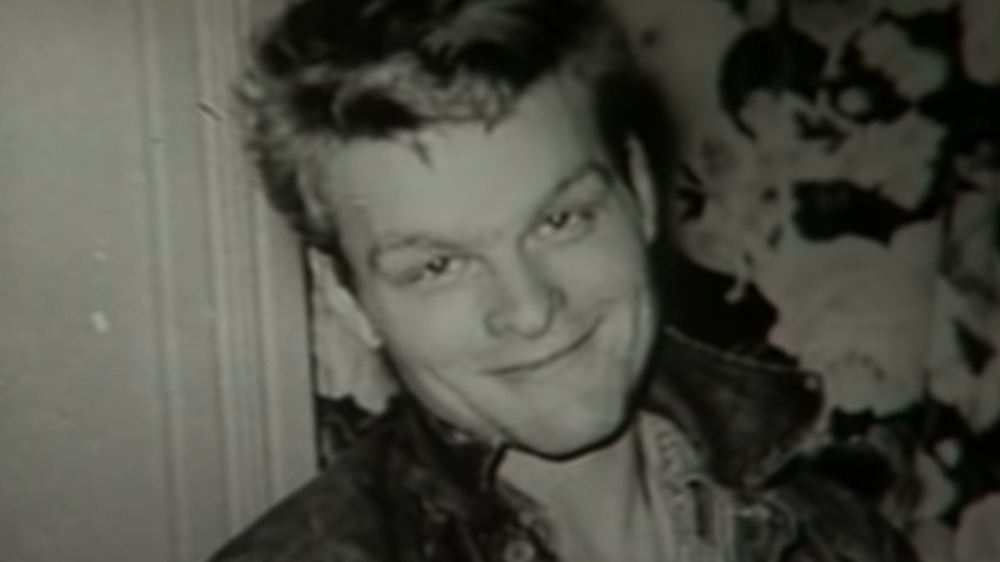

Starkweather homicide: a murder spree

After Charles Raymond Starkweather and Caril Ann Fugate, now known as Caril Ann Clair, were arrested in connection with 11 murders in Wyoming and Nebraska, the national media became obsessed. According to Lincoln Libraries, the Starkweather case became "one of the most heavily publicized mass murders in U.S. history, drawing national attention both to Nebraska and to the psychological issues surrounding disaffected youth."

Clair was 14 years old when she dated 19-year-old Starkweather for a few months. But after breaking up with him on Jan. 19, 1958, she came home two days later to find him there, claiming that he was holding her family hostage and that they would be killed if she didn't follow his instructions, according to WyoHistory.

Many newspapers were claiming that they were guilty well before the trial's verdict was given, and reporting of this trial was highly sensationalized. Both Starkweather and Clair were tried as adults and found guilty of murder, despite Clair's contention that she was a hostage, something she continues to assert as of 2020.

Starkweather was executed by electric chair on June 25, 1959, and Clair was sentenced to life in prison, although her sentence was commuted in 1973 from life to 30 to 50 years. She ended up spending 17 years imprisoned before being paroled in 1976.

Children of thalidomide: five years of uncertainty

In the 1950s, thalidomide was developed by Chemie Grünenthal GmbH, a West German pharmaceutical company. The London Science Museum writes that although thalidomide was initially meant to be prescribed as a sedative, before long it was being used to treat a variety of illnesses, including morning sickness for pregnant people.

And since early tests had determined that "it was virtually impossible to give test animals a lethal dose of the drug," it was considered harmless. By the mid-1950s, thalidomide was being marketed in 46 different countries. However, scientists didn't consider the notion that the effects of a drug could affect a fetus, and it ended up taking "five years for the connection" to be made between thalidomide and its effects on fetal development.

According to Helix, thalidomide interfered with fetal development, since it could affect hearing, eyesight, limbs, and/or internal organs. Often, babies were born with phocomelia, "resulting in shortened, absent, or flipper-life limbs." In 1962, thalidomide was either banned or given a warning label.

Smithsonian Magazine writes that thalidomide wasn't a problem in the United States because Frances Oldham Kelsey, who worked for the FDA, repeatedly rejected their application. "Kelsey found the clinical trials to be woefully insufficient in that the physician reports were too few and they were based largely on physician testimonials rather than sound scientific study." As of 2021, the FDA only approves the use of thalidomide as treatment against leprosy or multiple myeloma.

Mafia: the Mafia revealed

Up until 1957, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover insisted that there was no such thing as the Mafia in the United States. Despite the fact that six years prior, the Kefauver commission "found plenty of evidence for interstate gambling, the rise of narcotics trade, and the infiltration of legitimate businesses and law enforcement offices by gangers," according to Smithsonian Magazine, the federal government refused to acknowledge the problem or get involved.

Slate writes that Hoover had insisted that there was no way that criminals were organizing across state lines, and that even if "crime syndicates" did exist, they were local operations that should be dealt with at the state and local level.

But after 58 members of the Mafia were arrested on Nov. 14, 1957, in Apalachin, N.Y., the FBI and the American public were forced to contend with the fact that the Mafia wasn't a series of small isolated operations. Mafia leaders from across the country, including New York, Florida, California, and Texas, were captured by state troopers. Charges were brought against 20 people, but although they were convicted for obstruction of justice and conspiring to commit perjury, three years later "the convictions were thrown out on the ground that no illegal activity had been proved." But at this point, no one could deny the existence of the American Mafia.

According to The New York Times, because of the Apalachin Meeting Trial, Mafia family were closed to new members until 1976.

Payola: the influence of DJs

Payola, a combination of "victrola" and "pay," once referred to the fact that vaudeville performers were bribed by music publishers to perform their songs. And although the medium changed from victrolas and vaudeville shows to phonographs and radio shows, bribes or "payola" for playing particular tunes were "an accepted fact of the business," writes Mental Floss.

It wasn't until 1959 that payola's "stranglehold over the radio industry was forcibly loosened," according to Vice. By that point, even a mid-level DJ was making "$50 a week, per record, to ensure a minimum amount of spins." Chicago DJ Phil Lind even once admitted that he was paid "$22,000 to play a single record."

Two DJs, Alan "Moondog" Freed and Dick Clark, ended up becoming the focus of the U.S. House Oversight Committee, although at least 300 DJs who'd accepted "consulting fees" were also brought in. However, Clark was barely chastised while Freed was charged with 26 counts of commercial bribery, given a hefty fine, and a suspended jail sentence in 1960.

According to Plain Text, part of the reason that Freed was made an example out of was the fact that his "unorthodoxy, particularly his racial progressivism, made him a large target." But Clark had also "quietly severed a variety of business connections that might've tarnished his image," which made it significantly easier to target Freed.

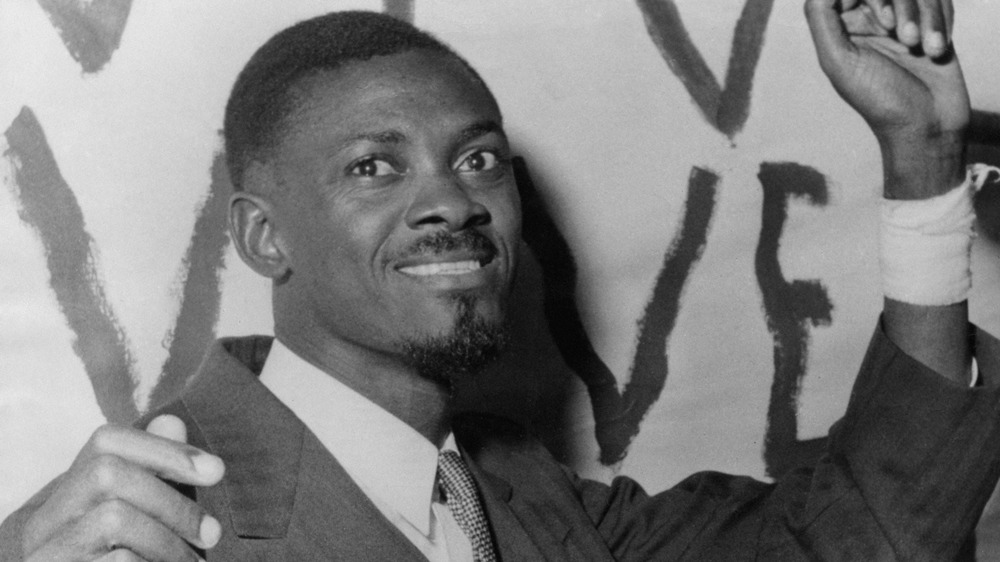

Belgians in the Congo: a proxy battle for the Cold War

The Democratic Republic of Congo declared its independence on June 30, 1960. But as Belgian business interests sought to keep a hold on the mineral industry, the country fell into a civil war. Black Past writes that soon after declaring independence, the army revolted, "demanding increased pay and the removal of white officers from their ranks." Meanwhile, the Belgian army also mobilized in the Katanga Province and, under the leadership of Moïse Kapenda Tshombe, seceded from the DRC.

According to Accord, Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba requested assistance from the United Nations, but Western nations, especially the United States, saw Lumumba's anti-colonial rhetoric as a threat to their own interests. As a result, assistance was given in exchange for Lumumba's removal from power. The Africa Report reports that President Joseph Kasavubu was finally convinced to dismiss Lumumba on Sept. 5, 1960, but after Lumumba refused to back down, the United States decided to back Joseph-Désiré Mobutu's coup d'état.

Meanwhile, Lumumba was assassinated on Jan. 17, 1961, in "a culmination of two inter-related assassination plots by American and Belgian governments, which used Congolese accomplices and a Belgian execution squad to carry out the deed."

Ole Miss: Segregationists riot

When James Meredith, a U.S. military veteran, tried to become the first Black student to enroll at the University of Mississippi in Oxford, Miss., in September 1962, Southern segregationists rioted. According to Black Past, state and federal troops had to be brought into the university, also known as Ole Miss.

James Meredith initially tried to enroll in 1961 but was denied admission by the university. After his lawsuit alleging racial discrimination was struck down, his appeal was upheld, and the U.S. Fifth Judicial Circuit Court ordered that Meredith be allowed to enroll. Federal marshals were sent to Oxford to prepare for the protest, but the evening before Meredith arrived, a riot broke out made up of KKK members, high school and college students, people from outside Oxford, and Oxford residents.

After Meredith arrived on campus, a crowd of 3,000 rioters gathered at Ole Miss. By nightfall, the riot had turned violent, and the white mob was shooting and throwing rocks at the U.S. marshals. Two men died during the riot, and over 300 were injured.

But by October 1, the riot was suppressed, and Meredith was escorted to his first class, which was "an American history course."

British politician sex: a government discredited

After it was discovered that John Profumo, secretary of state for war for the United Kingdom, had lied to the House of Commons about his affair with 19-year-old model Christine Keeler, he was forced to resign in 1963. But the ensuing scandal discredited Harold Macmillan's conservative government so much that Macmillan himself also resigned. The Irish Examiner reports that "in the general election that followed in 1964, the Labour Party led by Harold Wilson emerged as the victors, perhaps the only real victors of the Profumo Affair."

The Profumo scandal didn't just involve Profumo though. According to History Extra, Keeler was also involved with Yevgeny Ivanov, a Russian naval attaché whom MI5 tried to turn into a double agent. The scandal was turned into a question of national security, despite the fact that it was "concluded that there had been no breaches of security arising from the Ivanov connection."

Stephen Ward, an osteopath and portrait artist, ended up becoming the scapegoat for the scandal, due to the fact that Keeler and her friend Mandy Rice-Davies, who lived at his flat, testified that some of the gifts and money they received was "paid to Ward for rent, electricity, and food while living at his flat."

Ward was "tried on a trumped-up charge of living off immoral earnings," but before his sentencing, Ward committed suicide on Aug. 3, 1963.

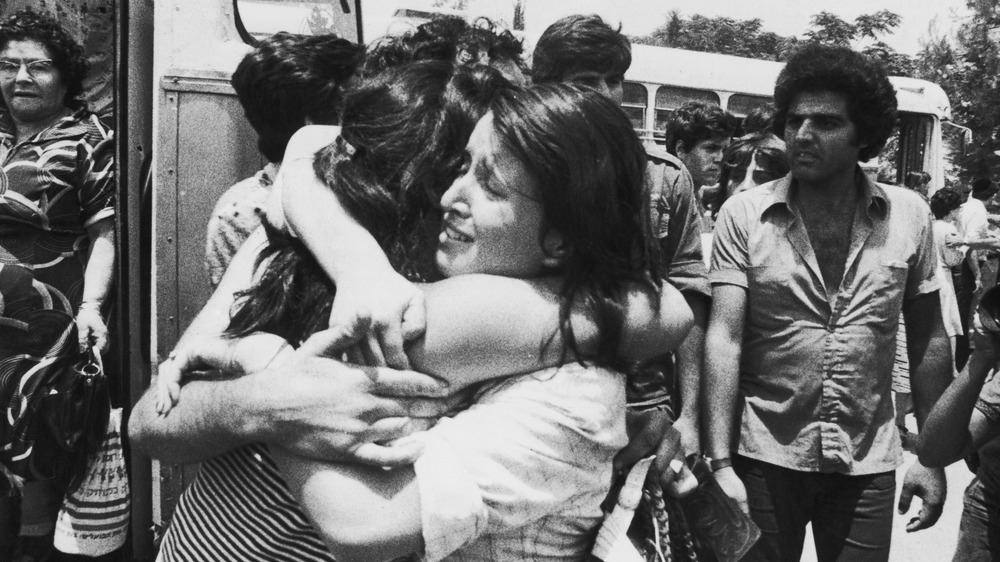

Terror on the airline: Years of skyjackings

In 1976 and 1977, there were numerous airplane hijackings. The most famous of the hijackings was that of Air France Flight 139 on June 27, 1976, which, according to NPR, was hijacked by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) and Baader-Meinhof Gang, also known as the Red Faction Army.

After departing from Tel Aviv to fly to Paris, the plane was redirected to Entebbe Airport, in Uganda, where the hijackers demanded $5 million along with the release of pro-Palestinians imprisoned in various countries. At one point, passengers who weren't Israeli or Jewish were released, according to The New York Times, although the flight crew chose to stay behind with the remaining hostages.

The Guardian reports that on July 4 1976, Operation Entebbe was carried out by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) in order to save the hostages. During the raid, three hostages were killed, and 102 were rescued. All the hijackers were killed during the raid, as were at least 20 Ugandan soldiers. Before Entebbe, the PFLP used hijackings to bring awareness to the occupation of Palestine.

"We were obliged to do it. It's not because we liked to, but because we didn't have the capacity to impose ourselves on the world. We have no land: it's occupied. We have no state: we are refugees... We had to ring the bell in a different way." But a few years after Entebbe, "the Palestine Liberation Organisation renounced 'the armed struggle.'"

Foreign debts: the lost decade

When Mexico informed the United States and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) that it wouldn't be able to pay its debts, "which at that point totaled $80 billion," it set off a chain reaction that resulted in a total of 27 countries worldwide defaulting on their sovereign debts.

Commercial banks had already been criticized in 1977 for their lending practices to Latin American and African countries, but by the time the debt crisis came around, nine U.S. banks "held Latin American debt amounting to 176% of their capital."

According to Federal Reserve History, "in response, many banks stopped new overseas lending and tried to collect on and restructure existing loan portfolios." This sent many countries into a recession, and ultimately led to practices that resulted in the debt crisis of 1997.

In Debt Defaults and Lessons from a Decade of Crises, Federico Sturzenegger and Jeromin Zettelmeyer write that after countries in Latin America and Africa lost access to international capital markets, "far fewer developing countries were exposed to significant levels of privately held debt than at the beginning of the 1980s." Instead, this lending boom went into the emerging markets of Asian countries, and "when the lending boom to these countries ended in 1997, the result was a private debt crisis that led to thousands of corporate defaults and debt restructurings in the Asian crisis countries." Because of this debt crisis, many now refer to the 1980s as a "'lost decade' for development in many underdeveloped countries."

Hypodermics on the shore: the chaos of the syringe tide

From 1987 to the end of 1988, the shores of Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York were littered with "a significant amount of syringes, other medical waste and raw garbage," and no one knew where it was coming from, reports the The New York Times.

According to NJ, beaches kept closing in response to the repeated tides of syringes, and at one point, the medical debris tested positive for HIV and hepatitis B. Comparatively, the Jersey Shore alone lost $1 billion of tourist revenue in just one summer due to the repeated closing of beaches. Thankfully, no one is reported to have been injured as a result of the medical waste.

According to Environmerica Team, the medical waste and spillage was linked to a landfill on Staten Island in 1987, and New York was forced to pay for the cleanup in addition to a $1 million fine for pollution damages (via The New York Times). But the following year, syringes were still washing up on various beaches.

As a result, in 1989, the Medical Waste Tracking Act was put into effect in order to "combat and address the illegal dumping of biohazardous waste." The act expired after two years, at which point the EPA gave the responsibility of handling medical waste over to state departments.