How Other Countries Teach American History

"History is a set of lies that people have agreed upon," said Napoleon Bonaparte (although he may not have coined the phrase, according to Quote Investigator). What if people accept the good general's cynical observation? What happens when people agree to different lies? Well, what is a lie? What is history? The answer to those questions will very often really depend on who the people in question are and what story they're telling. Which is exactly how world history works.

As much as history is anything, it is the stories people tell themselves about themselves. In fact, the first entry for Merriam-Webster's "history" is "Tale, Story." Different people have different stories, however, sometimes the same story will be different depending on who's telling it. American history can yield a much different set of stories, some of the characters appear far different, depending on whose history people are reading.

The Korean War according to North Korea is very different

The Korean War technically hasn't ended yet. Military service members stationed in South Korea right now are eligible to join the Veterans of Foreign Wars, even though a ceasefire was declared in 1953. Unfortunately, Americans know so little about this conflict that it is often called the "Forgotten War." It isn't forgotten in North Korea, however, and what they learn about it is alternately hilariously profane, offensively inaccurate, and deeply chilling.

A North Korean textbook quoted in a paper published by the State University of New York at Cortland reverses how the war started, claiming they were attacked — "On June 25, 1950, the American imperialists ordered puppet South Korean forces to attack the north..." Negotiations and peace talks, explains the textbook, were barbaric tricks — "Through the talk, the bastards tried to gain a 'glorious' cease-fire by realizing their aggressive purposes." During the war, the textbook says, with no evidence and contradicting every account of all the United Nations forces who were there, Americans "used atomic bombs and biological weapons to kill North Korean Prisoners of War."

At North Korea's Museum of American War Atrocities, as described by Newsweek, full-size dioramas show U.S. soldiers committing graphic war crimes liking murdering women with nails to their heads. "The Americans are slaughterers who brutally massacred our people," says the museum tour book. The museum tour guide, said Newsweek, "repeatedly referred to Americans as miguk nom, or 'American bastards.'"

The American Revolution isn't a big deal in most countries

Scholars argue whether the American War of Independence is the most important event in U.S. history, but for most countries it barely registers a mention in their history books, let alone in their schools. It probably shouldn't be a surprise that most countries dwell more on their own origins than on America's, but most of them don't even teach it at all and really, why would they?

The countries that do teach about the American Revolution generally include it as part of the curriculum on the Enlightenment, according to Quartz. It's given a bit more attention in France perhaps due to the French involvement in the American Revolution, and generally they teach it as prelude to their own, arguably more globally important, eponymous Revolution – and the orgy of bloodshed that followed it.

Not even the country America fought a revolution against really cares about it. As a 17-year-old British student told The Washington Post, "We don't get taught anything about America." The Post quotes a Glasgow University professor who estimated that fewer than 10% of British students studied the American Revolution. "Our history goes back to the time of the Romans," said the director of the Centre for American Studies at the British Library, "so quite frankly, the American Revolution doesn't figure very highly."

How a country teaches 9/11 depends on its relationship with America

For many millions of Americans the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, were the single most important event of modern history. For historians, the attacks were one of the most documented, well-covered, and universally known international incidents they could imagine. However, textbooks around the world treat 9/11 very differently. Researcher and photojournalist Elizabeth Herman explained to WBUR "that a country's relationship with the U.S. often influences how it teaches about 9/11."

Herman described subtle differences that enunciated a larger narrative, as in how adjectives and pronouns are used to obscure the facts of what happened. "On September 11, 2001," says a Pakistani textbook, "American Trade Center and other strategic positions were attacked by unidentified terrorists." Other countries, like Turkey, remove any reference to the attackers as Muslims. Still others use words like "incident" instead of "attack."

Many large countries, especially geopolitical or economic rivals, Herman says, are apt to focus less on the events of the day and more on what happened before and afterwards. She suggested that the most different interpretation, almost a complete reversal of what American students learn, may be in Chinese schools where, "It mostly spoke about 9/11 as a sign of diminishing American hegemony — and that is not what you see in American textbooks. You see 9/11...as a sign of America having been attacked and then having come together."

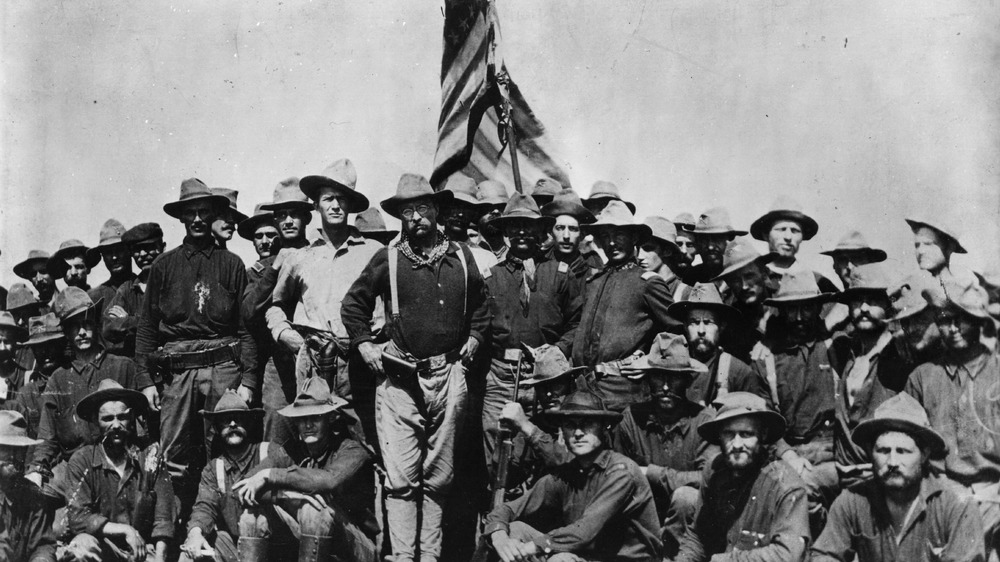

The Spanish American War started because the U.S. sank its own ship

In American schools, the Spanish-American War is generally taught with one or two dominant themes. First, as these classroom materials from the Library of Congress show – "The Spanish-American War: The United States Becomes a World Power." Second, as these interactive lessons from PBS Learning Media show — "Imperialism and the Spanish-American War."

In their book, History Lessons, authors Dana Lindaman and Kyle Ward (per Edutopia) also compare how the Spanish-American War is taught in Spain and the Philippines. The Spanish seemed the most sanguine about it, focusing on the reasons the Spanish Empire was dying in the first place and got beat by the upstart Americans who "hardly had a professional army."

Textbooks are far more blunt in the Philippines. They had joined the Americans in fighting the Spanish but, "The Filipinos, who expected the Americans to champion their freedom," Lindaman and Ward quote from a textbook, "instead were betrayed and reluctantly fell into the hands of American imperialists." According to the U.S. State Department Historian, immediately after America took possession from Spain, "fighting broke out between American forces and Filipino nationalists." In the Philippines, the war was deliberate imperialism. It wasn't started by the USS Maine sinking by accident, as is thought now, or by Spanish saboteurs, as American propaganda claimed for decades — "...the Maine had been blown up by American spies in order to provoke the war."

In Canada, the U.S. lost the War of 1812

The War of 1812 is a little-known affair for most Americans. Some students may learn about the burning of the White House and the origin of the Star-Spangled Banner, but the War of 1812 was, as the Harrison, N.Y., Public Library describes in their help section, "The War Nobody Won; The War Nobody Lost and The War Nobody Remembers." But, as far as our northern neighbors are concerned, Canada totally won.

First of all, for Canadians, Americans "are viewed as the aggressors and invaders in that war," the chief curator for Toronto's Museums and Heritage Services explained to Smithsonian Magazine, "No two ways about that." In fact, the infamous sacking of Washington, D.C., and torching of the White House was retaliation for the American invasion of Toronto.

Canadian public school teacher Bryce Honsinger told NPR that, in contrast to at most one or two days that American schools spend on the war, his students are given "between three to four weeks." He teaches that the war is essential in understanding Canadian history and identity. "Many Canadians would consider that we won that war because we are not American. We were fighting one of the great powers to be in the world and we were able to beat them back."

For many Africans, there was no slave trade

Slavery in North America had a long history before coming to a climactic end in the Civil War, an event of much focus in American schools where students learn about Harriet Tubman, the Underground Railroad, and slave ships from Africa. According to the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, somewhere around 12.5 million people "departed Africa for the Americas." An average of 304 people were taken per trip, on around 40,000 individual voyages, the vast majority headed towards South and Central America. Less than 3% of African slaves went to North America, but it turns out that American schools teach more about it than many African ones do.

Many slaves left from Ghana, which was for over a century the center of British slave-trading on Africa's west coast. After the end of slavery, said local historian Nat Amarteifio to The World, "The chiefs and peoples decided, 'All right, we will not talk about it,'" he said. "They created a mythology that we were innocent bystanders whose land was raped by Europeans." Europeans couldn't just come and kidnap Africans, Amarteifio explains, malaria kept them away, so instead, "Some African ethnic groups went into business," capturing and selling their enemies. Mona Boyd moved to Ghana from Arkansas and now operates a travel agency for African Americans. "Most Africans, when I came to this country," she said to The World, "would not admit that [the slave trade] even happened."

China and Korea really hate Japan's history books

World War II is probably the best known conflict in history. As it should be, according to the National World War II Museum, at least 60 million people died. China bore a huge share of that body count, up to 20 million (although, the Museum notes, China claims 50 million). Americans learn that the country joined the war in 1941, and the war started in 1939, learning that the Nazis were cruel and Japan attacked Hawaii. In China, the war started in 1937, and Chinese students learn that Japan was the bad guy — in a major way. Korean schools teach about the literal decades of cruelty they faced under Japanese occupation. However, some Japanese textbooks present a far different narrative, angering their neighbors.

DW reported on "a history text book used in more than 50 junior high schools across Japan" that ignores much of that country's atrocities and war crimes. The conspicuous absence in the textbook of the mass assaults, beheading contests, and more than 300,000 deaths of the 1937 Nanjing Massacre drove Beijing to complain to Tokyo. The hundreds of thousands of Korean women and girls forced to work as sex workers for the Japanese army are not mentioned, prompting outcry in Seoul. Hiromichi Moteki, chairman of the group that wrote the book, told DW that Japan is "not responsible for any wrongdoing and we cannot understand why China and Korea refuse to accept that."

Germans don't really learn about D-Day

On June 6, 1944, the end of the Nazi regime was finally in sight for the Allies. That's what most Americans learn in school. D-Day, a liberating force of over 150,000 men landing at Normandy to begin the crushing blow to Germany, is memorialized in everything from Call of Duty to Saving Private Ryan. Except that's not quite the story in Germany itself. Stars and Stripes spoke to German students at the University of Heidelberg for the 60th anniversary of the D-Day landings about what they learned about D-Day and World War II in schools. According to German schools, while the Allies were liberators and D-Day important, the Americans had far less to do with defeating Germany than Russia did.

"The fighting job was done by the Russian Red Army mostly," said 22-year-old Philipp Trein. "The fighting was done in Russia, not so much in France." Which actually jives with what most of the world teaches about World War II, which may have something to do with the fact that, according to the National WWII Museum, up to 80% of German casualties were on the Eastern Front. Eleven million Russians died in WWII but only around 400,000 Americans. In fact, D-Day itself is barely taught at all, evidenced by 19-year-old Anna Fischer's reaction, "'Saving Private Ryan?' Oh, that's D-Day."

Columbus Day is very different in South and Central America

No matter how you slice it, Christopher Columbus was a pivotal figure in history, and his voyage to the Americas eventually changed the world. He is certainly remembered mostly respectfully in the U.S. "In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue" explains the poem that every American elementary school kid knows the first line of. Columbus Day is an official federal U.S. holiday and, according to The Business Journals, almost 3 million Americans live in 54 different communities named after Columbus.

Columbus is only "mostly" fondly remembered by Americans. However some Americans have different cultural memories, demonstrated by an updated version of the 1492 poem, published in Indian Country Today – "But everything else in the childhood rhyme, Ignores the historic details and genocide." In fact, tens of millions of Americans don't actually celebrate Columbus Day, as shown by Pew Research. The legislatures of 12 states plus Washington, D.C., have renamed it after the native or Indigenous people on the receiving end of his "discovery."

Columbus' legacy in South and Central America is evolving. While he is remembered in the U.S. for discovery, in places like Venezuela and Nicaragua, per NPR, the Day of Indigenous Resistance marks his colonial brutality. Columbus Day has been replaced, Culture Trip explains, by the Day of the Discovery of Two Worlds in Chile, the Day of Respect for Cultural Diversity in Argentina, and the Day of Decolonization in Bolivia.

The Cold War in Russia is complicated

Russia is the biggest country in the world and was, as the USSR, the first communist country in history. For 70 years, the USSR was the most influential communist country on the planet and for most of that time, America's biggest adversary. The Cold War basically started immediately after World War II and lasted until the USSR collapsed in 1991. This story is easily told in America — USA still here, USSR gone. Simple. Not so simple in Russia. In an excerpt from his book, (subtitled) The Cold War in Russian History Textbooks, Russian historian Alexander Khodnev examines how Russian schools approach the Cold War in the 30 years since it ended.

Khodnev says that immediately after the USSR collapsed, revisionist historians taught that it was responsible for starting the Cold War. Now two main narratives about how the Cold War dominate in Russian textbooks — the USA started it, or the USSR and USA share responsibility. He notes that while the textbooks do criticize Soviet leaders and various Soviet actions, there is little time spent on the standards of living for Soviet citizens and "categorically do not recognise the occupation of Eastern Europe by the USSR." The Russian government "directly require schools to mould students into patriotic citizens through the teaching of history..." And, Khodnev says, "...a patriotic master narrative dominates in modern history textbooks in Russia."

It isn't the Vietnam War in Vietnam

The Vietnam War is a sore spot for many Americans. As a war, America lost some 58,000 lives, millions took to the streets in protest, and, as Rewire explains, "The United States won almost all of its battles against the Viet Cong, but the communists still won the war." Teaching the Vietnam War is a source of controversy "that [goes] back to the 1960s," and, says Perspectives on History, "live[s] on in classrooms today." Not so much in Vietnam.

First of all, they call it the American War, and many of you reading this just went "Oh, duh!" and you know it. Second of all, they won. In Vietnamese schools, "We learned that even though the U.S. army was really mighty and their weapons were really modern," a Hanoi university student told The Atlantic, "the Vietnamese country united and stood up for our freedom."

Vietnamese begin learning about the American War in elementary school. Said another Hanoi student, "Each year, we learn the same thing in more detail. America started the war to help France get Vietnam back." Details of how many Americans were killed and tanks and planes destroyed litter Vietnamese textbooks, but little attention is paid to more than 1 million North Vietnamese fighters killed. "It's war, so Americans have propaganda and we have it too," said a retired high-school teacher. "It's inevitable."

Nordic students are taught their ancestors discovered America

Nearly 500 years before Christopher Columbus sailed the ocean blue to land in the Bahamas, the Icelandic explorer Erik the Red did it first, landing in Greenland. However, Americans have a Columbus Day now, in large part because Italian-Americans lobbied the government more successfully, according to NPR, than a similar "movement going on to promote the Viking explorer Leif Erikson" (Erik's son is widely considered to be the first European to set foot on the American continent). President Calvin Coolidge actually publicly supported the Viking claim, but FDR ended up going with Columbus in 1934.

In Iceland, they are keenly aware that their ancestors discovered, and for a short time made their home in, the New World. The Saga of Erik the Red and The Saga of the Greenlanders were written, according to Smithsonian Magazine, some two or three centuries after the great Viking adventures they describe. They detail how Erik discovered and created a colony in Greenland, and how his son Leif discovered and plundered Vinland, what they called North America. Icelandic children learn in primary school that "Leifur" discovered the New World and play Great Adventurer, role playing the Viking heroes. Some researchers suggest, Smithsonian reports, that if it wasn't for the climate event known as the Little Ice Age that "some of North America might be speaking Norse today." If nothing else, it seems certain history would be taught a bit differently.