The Untold Truth Of The Forgotten Women Refugee Scientists Of WWII

When Jewish refugees came to the United States during World War II, history often repeats such famous names as Albert Einstein, Enrico Fermi, and Hannah Arendt. But they were not the only intellectuals who attempted to flee Nazi-dominated Europe. Hundreds of other scholars and professors tried.

Among them were several highly qualified women scientists who looked to American universities to find a safe haven where they could continue to pursue their careers. In spite of their academic achievements, they encountered many obstacles, and their journeys were often arduous during a time when leaving Europe was becoming increasingly difficult.

Caught between the anti-semitic laws in their country and the bureaucratic difficulties of getting a visa to the U.S., for many of them it wasn't just about getting a job, it was a matter of life and death. Some of them made it, others unfortunately did not. Here are the riveting, untold stories of the forgotten women refugee scientists of WWII and their struggle for survival.

At least 80 Jewish women scientists were forced to flee Nazi Europe

In April of 1933, the German government issued a new law (Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service), which banned Jewish people and political enemies of the Nazi party from all civil service positions. According to the Smithsonian Magazine, it didn't matter whether or not people were "active worshippers," belonging to a Jewish family was ground enough for discrimination. "All public sector employees were required to provide a so-called certification of Aryan ancestry documenting their racial purity," German History reports.

This meant that many university professors and scholars were not allowed to work in universities in Germany and Eastern Europe. "In some disciplines and faculties this was a huge number of people, one-third of them Jewish or of Jewish descent," says professor and journalist Laurel Leff, per the Smithsonian. According to the official numbers, about 12,000 Jewish academics were fired from universities in Germany alone. Northeastern University identified the names of at least 80 women among them.

As WWII approached and more anti-semitic laws came about, for many, Jewish professors and educated people staying in Europe wasn't an option. But for the 80 women scientists who were forced to leave the question was, where to go?

Many of the women had doctorates

Many of the women scientists who were forced to flee their countries were pioneers in their fields and held advanced degrees in science and mathematics, which wasn't common for women at the time. According to the data collected by Northeastern University, most women were academics, professors, and practicing scientists. But being a female scholar in the male-dominated world of academia wasn't easy, even in pre-Nazi Europe. "Some found work in universities, but others took jobs in labs or practiced as scientists outside of academic institutions," Northeastern reports.

The 80 women scientists profiled by Northeastern University were born between 1890 and 1915, and by the time the Nazis rose to power, they had already established a career in their respective fields. They were experts in different disciplines, but the majority of them practiced as chemists, biologists, and psychologists. According to Northeastern, the women scientists who applied for aid to emigrate to the U.S. "overwhelmingly spoke German, French, and/or English."

Most of them were educated in prestigious institutions in Berlin and Vienna, which were the cultural centers of German-speaking Europe at the time. Regarding their ethnicity and religious beliefs, it's harder to establish exactly where they belonged, since that kind of information was kept secret, understandably so, given the circumstances. They were simply defined as "non-Aryan," per Northeastern.

The 1924 Immigration Act made it hard to enter the U.S.

In the early 1920s, as living conditions in Europe worsened and more and more people sought to immigrate in the U.S., the American government was pressured to limit the number of people who came into the country. According to the Office of the Historian, in 1917 the U.S. government had already placed restrictions on immigration, introducing a literacy test and capping the total number of immigrants at 350,000 per year.

In 1924 the U.S. government passed a new immigration law, also known as the Johnson-Reed Act, which introduced a new quota based on national origins. Basically, the new law stated that only 2% of the total number of people of each nationality already present in the U.S. could enter. This meant that large quotas were given to British people, while the number of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe allowed in the U.S. was very limited.

Not only that, but Japanese and Asian people were completely excluded from entering the U.S., and the number of immigrants permitted every year was lowered to 150,000 (via Smithsonian Magazine). "The most basic purpose of the 1924 Immigration Act was to preserve the ideal of U.S. homogeneity," the Office of the Historian reports. The new immigration law made it extremely hard for Jewish refugees across Europe to seek asylum in the U.S.

Only four women received official aid

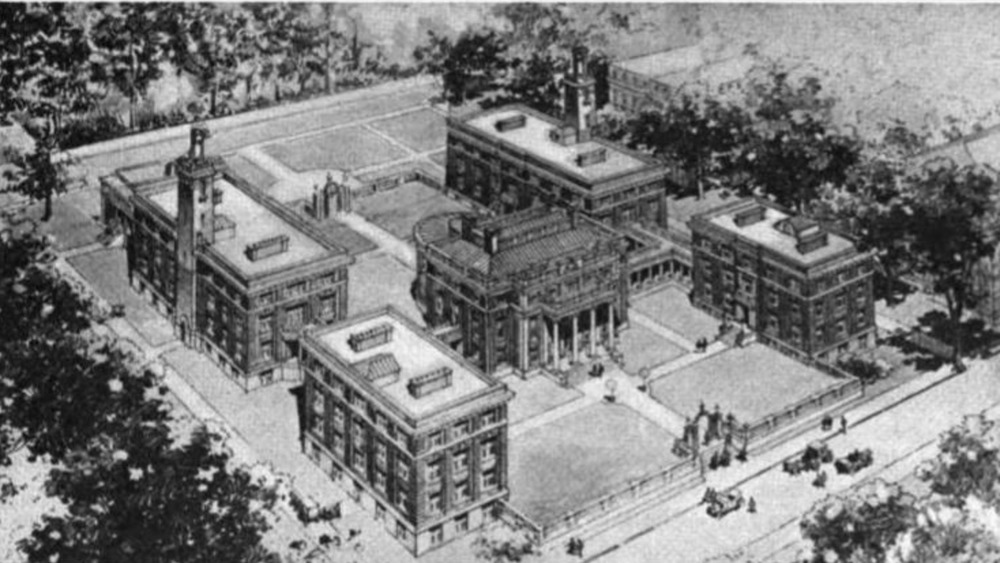

Because immigration was heavily restricted by the 1924 law, a committee was created in New York to help displaced professors. The Emergency Committee in Aid of Displaced Foreign Scholars was founded in 1933 by educator Stephen Duggan, with the support of the Rockefeller Foundation, with the purpose of helping persecuted scholars find shelter in American universities.

But applying for aid wasn't an easy task, and it wasn't a guarantee to find work. According to Northeastern University, "over 5,000 scholars, including 80 female scientists and mathematicians, sought the help of the Emergency Committee in Aid of Displaced Foreign Scholars," but Smithsonian Magazine reports only four received grants.

The four women were Hilda Geiringer, pioneer in the field of applied mathematics who, after fleeing Germany, taught in Brussels and Istanbul before landing a position at Bryn Mawr College; Emmy Noether, considered "the most accomplished female mathematician of her time," also found a job at Bryn Mawr, recommended by Albert Einstein; Hedwig Kohn, doctor in physics, known for her research in the field of radiology, was offered a contract at Women's College of the University of North Carolina and later at Wellesley; and Tilly Edinger, whose important research in the field of paleoneurology earned her a position at Harvard, Lady Science reports.

Fortunately more women were still able to emigrate to the U.S.

Only a small percentage of scholars received official aid from the Emergency Committee, but thankfully a few more were able to make their way in the U.S. through a loophole in the law. According to Smithsonian Magazine, if a professor received an offer to work at a university, he or she was allowed to immigrate on non-quota visas. "With the help of the Rockefeller Foundation, the Emergency Committee began collecting resumes and CVs from European scholars seeking work in the U.S. and tried to place them in American universities," per the Smithsonian.

The Emergency Committee worked closely with universities to secure teaching positions for some of the women scientists who applied for aid. The way it worked is that when they needed to fill a position, universities suggested to the committee the names of foreign-born scholars who had applied for a job. But for the many women who were waiting for an answer, this could be a long and excruciating wait. "Ultimately, universities decided which scholars were, quote, 'worth saving,' in the unfortunate phrase of the time, and the State Department decided whether they were to be saved," writes professor and journalist Laurel Leff in her 2019 book, Well Worth Saving: American Universities' Life-and-Death Decisions on Refugees from Nazi Europe, via Lady Science.

It was hard to get a job at an American university

"Between 1933 and 1941, only 944 professors across all disciplines received non-quota visas," Lady Science reports. But why was it so difficult for Jewish scholars to get a job in the U.S.?

One of the reasons was anti-semitism. As professor Laurel Leff wrote,"to get a job in an American university, it was really helpful not to be Jewish," per Smithsonian Magazine. Sadly, many universities were reluctant to hire Jews and preferred American-born professors over foreigners. Some colleges even went as far as stating they would only hire "Aryan" applicants, the Smithsonian reports.

Age was also an issue. According to Lady Science, many of the women scholars were well into their career when they arrived in the U.S. and were considered too old to be hired. Others, on the other hand, were too young to have had enough recognition in their field and therefore to be offered a teaching position.

And even when they met the requirements, simply sending an application wasn't enough. Women scientists looking for a job at an American institution needed a connection, somebody who was established and could vouch for them. As Leff aptly puts it, "having money helped. Being a woman did not," via Lady Science.

Many women scholars had to take jobs that had nothing to do with their career

Even when women scientists were admitted to the U.S., it was hard for them to continue their academic work as researchers. Not only they had to be highly accomplished and recognized in their field, they also needed to be "working in disciplines for which the American Academy had a recognizable need," said Laurel Leff via Lady Science.

As a result, highly qualified women scholars often had to settle for lower paying jobs at universities that were not equipped with the laboratories they needed to continue their work. Still, they could consider themselves lucky. Some of them were forced to take jobs as nannies or caretakers, putting their professional careers on hold. According to Smithsonian Magazine, "Many of the women scholars came to the United States working as domestics, at which point they would apply to the Emergency Committee for help finding work in academia rather than as cooks or childcare providers."

But for many of these women it wasn't a choice. When confronted with the reality of things, "it wasn't simply a matter of getting a job in their field; the stakes were life and death," as journalist Lorraine Boissoneault wrote, per the Smithsonian.

They were discriminated in universities because of their gender

Being a Jewish refugee didn't help, and neither did being a woman. When they were able to find a teaching position, women scholars suffered discrimination because of their gender. According to Anna Reser and Leila McNeill, authors of Forces of Nature: the Women Who Changed Science, it was hard for women refugees to get a position at ivy league universities, regardless of their merit or accomplishments in their fields.

Emmy Noether was one of the leading mathematicians of her time, who expanded on Einstein's Theory of Relativity and discovered what is studied today as Noether's Theorem. But it wasn't enough to get her a job. Noether's application was rejected by Princeton, which she called, "s men's university which admits nothing female," per Lady Science. Noether ended up having to take a position at Bryn Mawr, a smaller women's college in Pennsylvania.

On top of that, section 4d of the 1924 Immigration Act openly discriminated against women, stating that the non-quota visas were available for any professor and "his wife and his unmarried children under 18 years of age if accompanying or following to join him," via Lady Science. Clearly, it was intended for male professors and didn't even take women into account.

The crazy story of Hilda Geiringer

During WWII, only prestigious and well funded universities such as Yale or Harvard were able to finance research. The women scientists who were hired to teach in smaller colleges often had to give up their ambitious careers.

It's what happened to scientist Hilda Geiringer. Born in Vienna in 1893, Geringer got her doctorate in mathematics. According to Northeastern, she emigrated to Germany where she became the first woman to receive tenure in the faculty of mathematics at the University of Berlin. In 1933 when Adolf Hitler was elected chancellor, Geiringer lost her job like many of her Jewish colleagues.

She fled first to Brussel and then to Turkey, where she worked as a professor at the University of Istanbul. In 1938 the government changed, and Geiringer lost her job again. She made her way to London, where she was sheltered at her brother's home, before embarking on a freighter to Lisbon, along with her daughter Magda. When the war broke out, they got stuck in Portugal for over a month waiting for their visas and almost risked being deported to a concentration camp.

In 1939, with the help of fellow scholar Richard Von Mises, she finally got offered a position at Bryn Mawr and was able to travel to the U.S. But there, she had to significantly lower her expectations, settling for a job she was overqualified for. "Despite her illustrious background in applied mathematics Geiringer was expected to teach basic courses in mathematics," Northeastern reports.

The tragic story of Leonore Brecher

Unfortunately, not all women scholars were able to find a safe haven. According to Northeastern, Romanian born scientist Leonore Brecher lost both her parents while she was a teenager. She moved to Vienna where she earned a doctorate in zoology. There, she studied butterflies, worked for the prestigious Vivarium at the Biological Research Institute, and received grants for her research by the Austrian Academy of Science.

In 1923 Brecher received a scholarship to continue her work at the University of Rostock in Germany. She applied for a research position in the department of zoology at the University of Vienna, but she was rejected. The committee, comprised of professors who shortly after would join the Nazi party, said that she was "unsuited to maintain the authority required of a lecturer over students," Northeastern reports.

Brecher went on to work at the University of Cambridge and was awarded a scholarship from the University of Kiel, before she eventually returned to Vienna. In 1938, when Nazi troops occupied Austria, she looked to emigrate to the U.S. In spite of her accomplishments and the pleads of the many academics who vouched for her, she was denied aid. In 1940 the Emergency Committee sent her a letter saying "there's practically nothing we can do to assist you, " per Northeastern. In 1942 she was deported to a concentration camp in Belarus, where she died on the day of her arrival.

They were not forgotten

While their stories have long been ignored, a lot is being done today to honor the memory of these courageous women. As Laurel Leff said, "those people deserve to have their stories told, too, not just the great scientists who develop the atomic bomb," per Smithsonian Magazine.

Under the guidance of professor and journalist Leff, Northeastern University has launched the project Rediscovering the Refugee Scholars of the Nazi Era, an online archive where a team of researchers, with the support of the New York Public Library, has been collecting and digitizing documents and testimonies around the lives of the Jewish scholars who came to the U.S. fleeing Nazi persecution. The project aims at preserving the stories and reconstructing the difficult journeys of the women scientists who were "Well Worth Saving," as Northeastern professor Leff said in her 2019 book, American Universities' Life-and-Death Decisions on Refugees from Nazi Europe. But it's only the beginning, and a lot of work still needs to be done.

The story of refugee scholars remains controversial

While the Emergency Committee and several other institutions in America helped many Jewish men and women scientists immigrate to the U.S., some are asking if more could have been done. "While certainly a lot of people escaped and were able to transform American culture [think Albert Einstein and Hannah Arendt], it wasn't everybody. It's a self-satisfied version of our history," writes Laurel Leff per Smithsonian Magazine.

The issue of Jewish refugees in American universities remains a controversial one, as more documents and testimonies became available over the years. "The 1930s are a moment of crisis. There's pervasive fear of foreigners, generated as a result of being in a deep depression. Often when you have those conditions in the United States, it makes it more challenging to live out some of our stated ideals about being a nation of immigrants or a land of refuge," says Northeastern history professor Daniel Greene, per the Smithsonian.