The Untold Truth Of Disgraced Entrepreneur Elizabeth Carmichael

The phrase "stranger than fiction" gets overused, but every now and then we're reminded of a true story that actually happened that is so crazy there's just no other way to describe it. With HBO's 2020 docuseries The Lady and the Dale, we were all reminded of just such an episode from history: If you wrote a thriller based on the story of Elizabeth Carmichael people would say the plot was too unbelievable.

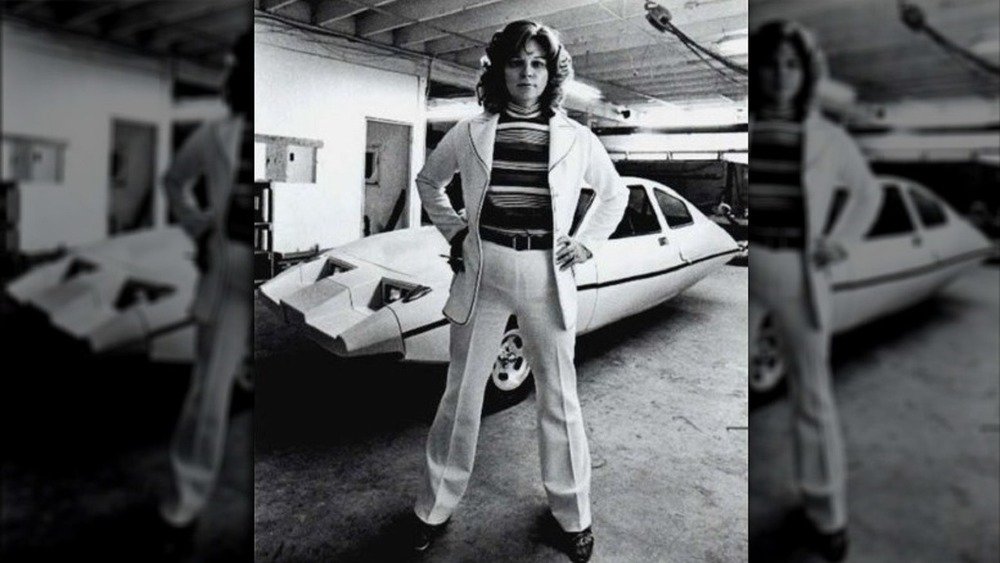

What really makes Carmichael's story so enthralling is its layers. It's almost impossible to summarize, because so many themes and bits of history intersect. You can view her story from a feminist point of view, or see it through the lens of a pioneering transgender woman. It's a crime story (there are, in fact, many, many crimes involved), but it's also an inspiring story of someone resolutely refusing to be defined by anyone but herself. It's also the story of a family that very obviously loved and supported each other through some very weird experiences. And it's all wrapped in some truly delightful 1970s fashion and car design.

Oh, yeah—it's also the story of a car. A car that was supposed to revolutionize the automotive industry but was never actually produced and never moved under its own power. Here's the untold truth of disgraced entrepreneur Elizabeth Carmichael.

Elizabeth Carmichael assigned male at birth

Elizabeth Carmichael was assigned male at birth in 1927, and named Jerry Dean Michael. Her early life was restless and messy; as reported by Esquire she married three times and had five children before meeting the woman she would spend the rest of her life with, Vivian. Oprah Magazine tells us that she deserted her first wife, Marga, and their two children in 1954. Then she married a woman named Juanita and had two more children, moving the family more than 20 times in the course of about two years as she tried to stay one step ahead of failed businesses and criminal schemes. She left Juanita and married Betty Sweets in 1958 after knowing her for just four weeks. They had a daughter together, but the marriage ended after one year.

Then Carmichael married Vivian Barrett. For the first time in her life, she told her wife the truth: She was a transgender woman named Liz. According to Oprah Magazine, Vivian was initially upset at this revelation and took their two children and left. Elizabeth wrote Vivian a touching love letter explaining her feelings and her identity, and Vivian was persuaded to return.

In the 1960s, being transgender was incredibly difficult—in every way. Elizabeth acquired the hormone injections she needed from veterinarians, and had to perform the injections on herself, and had to go to Mexico to get breast implants.

Elizabeth Carmichael took her family on the run

Money—or at least the pursuit of it—defined Elizabeth Carmichael's existence. Oprah Magazine notes that Elizabeth's youth was marked by several arrests, and she was fired from several jobs for skimming money. When she met her fourth wife, Vivian, she'd already left behind a trail of failed enterprises—and after their marriage she worked with her new brother-in-law, Charles, making fake IDs and writing bad checks. As reported by Esquire, she owned a newspaper in the early 1960s, and the printing presses gave her an idea: She began printing counterfeit money on the side. In August 1961, she was arrested on counterfeiting charges. Out of jail awaiting arraignment, Elizabeth made the fateful decision to skip town, taking a pregnant Vivian with her.

According to The New York Post, Elizabeth Carmichael and her family were on the run for years, moving frequently to stay one step ahead of warrants for her arrest—and landlords demanding rent. In fact, Elizabeth once quipped to her family that "moving is cheaper than paying rent." She and Vivian grew their family the whole time, eventually having five kids while they evaded law enforcement. They used stolen records to create new identities on a regular basis—and homeschooled their kids.

She faked her death

Living life on the run takes a toll—as does not living your truth. After living the ragged life of a fugitive for several years, constantly moving her family around the country and trying to eke out an existence using fake identities, Elizabeth Carmichael decided to stop running—and as reported by The New York Post, decided to fake her own death to get a fresh start.

She drove her car into a tree one night on a deserted road, making sure to leave some blood behind for identification purposes. LAist reports that she also shot up the car with a gun in order to make it look like she'd been murdered. According to her brother-in-law Charles, Elizabeth went underground for a while after that in order to ensure the scheme worked.

By faking the death of "Jerry," Elizabeth Carmichael was able to finally live life totally on her own terms as a transgender woman. As noted by Esquire, when she re-emerged officially under her new identity as Elizabeth, she came prepared with a backstory. She claimed to have studied structural engineering at Ohio State University, and invented a deceased husband named Jim, also a structural engineer. She often introduced her wife Vivian as her secretary, or her sister-in-law.

Elizabeth Carmichael met Dale Clifft while working in marketing

Elizabeth Carmichael faced several challenges when it came to supporting her family in the late 1960s and early 1970s. For one, she was a criminal living under an assumed identity. For another, she was a transgender woman at a point in history that was not at all friendly to the trans community. As a result she faced some pretty bleak employment prospects, but Elizabeth persevered and according to The New York Post landed a job with the United States Marketing Institute in California, a company that provided advice and guidance to inventors hoping to market their ideas. As reported by Esquire, that's where she met the man who would alter the course of her life, Dale Clifft.

Clifft had invented a three-wheeled car design. Technically a motorcycle, Clifft thought it had potential as a dune buggy of sorts—a lightweight, affordable recreational vehicle. Carmichael saw much more potential in the design—she thought she saw a potential solution to the energy crisis that gripped the country in the early 1970s. Here was a cheap car that could offer excellent gas mileage, with a finished design ready to go.

Carmichael worked out a deal with Clifft, licensing the rights to his design and naming the car The Dale in his honor. She launched the 20th Century Motor Car Corporation to manufacture it.

Elizabeth Carmichael was a skilled con artist

Elizabeth Carmichael was many things—a parent, a criminal, a loving spouse—but above all else she was a con artist. An exceptional con artist. While the design for The Dale, licensed from Dale Clifft and the founding product of the 20th Century Motor Car Corporation, was real enough, Carmichael set about creating hype for it that would have been nearly impossible to deliver on.

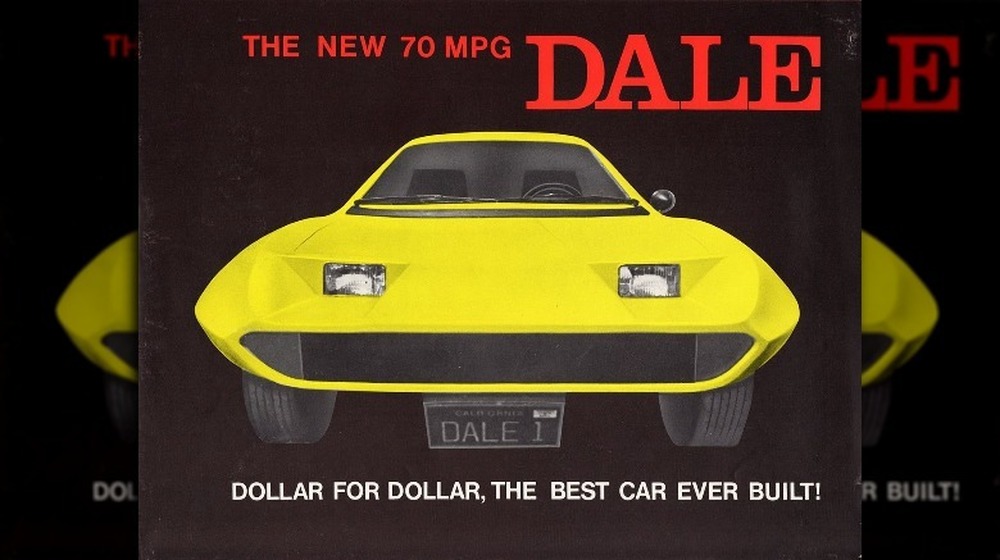

As reported by Car and Driver, Carmichael told the press that The Dale would utilize two BMW motorcycle engines, with a total of 40 horsepower and a top speed of 85 MPH. At the same time, the car would weigh less than 1,000 pounds, get 70 miles to a gallon of gas, and—most incredibly—cost less than $2,000 (which would be about $12,000 in today's money). Oprah Magazine reports she made outlandish claims, too—like saying the car was bulletproof, or that it could drive underwater.

Carmichael built a myth around herself and her company as a David going up against Detroit's Goliath, claiming she would revolutionize the industry. According to Esquire, the claims she made about The Dale weren't lies—the car could have met those standards in time. But she never gave them that time because she was impatient to cash in, trying to sell stock in the company without going through the proper legalities. The shame of it is The Dale might have succeeded if Elizabeth Carmichael hadn't been so impatient.

Elizabeth Carmichael was outed on live television by Tucker Carlson's dad

Elizabeth Carmichael was a transgender woman living a very public, very loud life at a time when trans people were treated horribly. As The Guardian reports, Carmichael seemed to thrive on the dangerous attention, wearing mini-skirts and sporting elaborate hairdos, often posing with her hands on her hips as if daring people to question her identity.

As reported by Esquire, a television reporter in Encino named Dick Carlson (Fox News' Tucker Carlson's father) launched an investigation into Carmichael and her company. Oprah Magazine reports that Dick Carlson is open about his transphobia, stating that one reason he went after Carmichael is because he was bothered by the fact that she looked "like a man." The Daily Beast notes that Carlson became "fixated" on Carmichael, went out of his way to refer to her using male pronouns, and insinuated that her transgender status was just a way to obfuscate her identity in order to get away with her crimes.

When Carlson found proof of Carmichael's trans identity, he didn't hesitate to reveal this extremely private aspect of her life—live on television. And Carmichael wasn't the only transgender celebrity Carlson outed in this way—he did the same thing to tennis player Renée Richards.

Elizabeth Carmichael ran her company in a totally sketch way

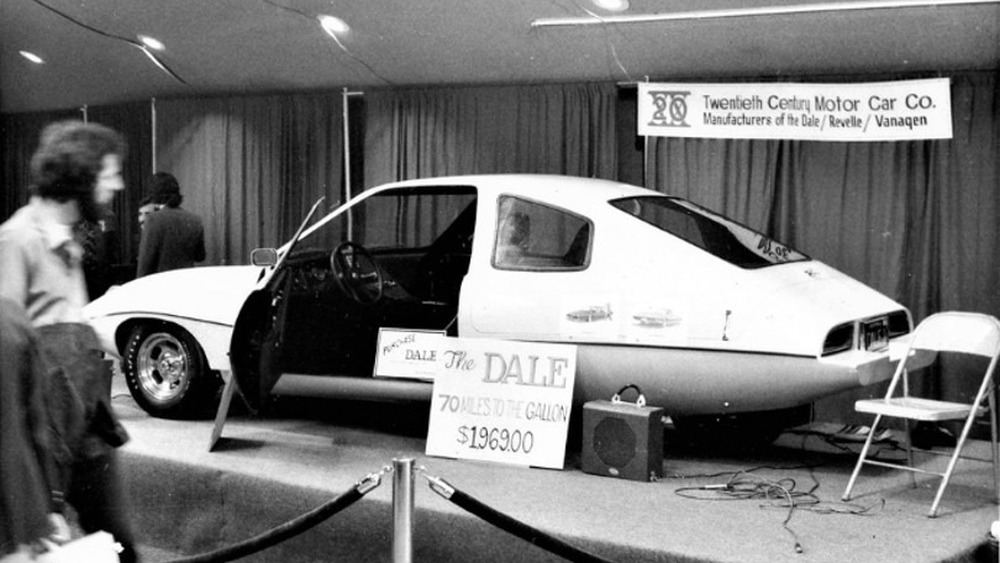

It might not be too surprising that a con artist with a long history of scams, criminal schemes, and fake identities ran her company with less-than ideal integrity. Elizabeth Carmichael launched the 20th Century Motor Car Company legitimately enough, licensing Dale Clifft's designs for what would be their flagship product, the three-wheeled car called The Dale. But things went wonky long before Carmichael's scheme came crashing down.

As The New York Post reports, the company had a before-its-time startup energy, described by some former employees as "a religious fervor." But even then, some employees recall being paid in cash—stacks of $100 bills—which wasn't the norm even in the early 1970s.

And as The Los Angeles Times notes, Carmichael was suspected of having ties to the mafia, and some employees reported seeing some shady characters who could have walked off a Scorsese set hanging around the company's offices. Put it all together and a lot of the people involved with Elizabeth Carmichael's company weren't surprised when she was indicted. And when the company imploded, it ended with a suitcase of cash being divided up between the executives and Carmichael.

The car never ran

The design of a three-wheeled car that Dale Clifft created was a real design—as reported by Esquire, with some effort it could have been developed into a running car. But as Bustle notes, that effort was never really made, and in the end only three prototypes of The Dale were ever built—and only one actually moved under its own power.

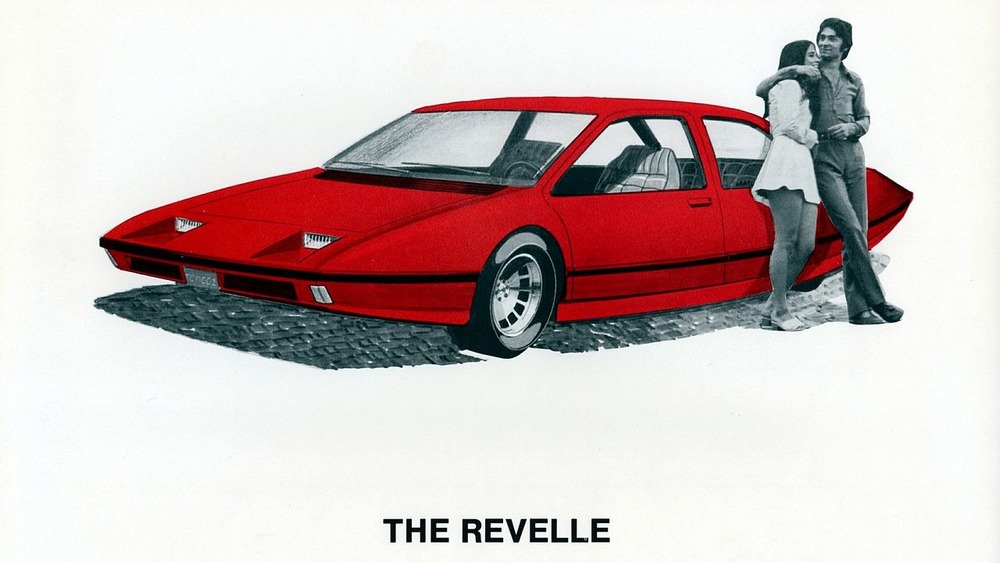

Not having a working car didn't slow Elizabeth Carmichael down. As The New York Post reports, one of her first coups was getting a shell of the car displayed at the 1975 Los Angeles Auto Show, which put a spotlight on the car. As Jalopnik reports, after renaming the car The Revelle in an effort to shed some bad publicity, she managed to get the car featured as the Showcase Showdown prize on The Price is Right that year—despite the fact that the car didn't actually run.

The only version of the car that actually moved under its own power, in fact, was cobbled together in a last-minute frenzy when potential investors demanded to see it. It barely moved, and almost tipped over when taking turns. The investors fled, and Carmichael was eventually indicted on charges of grand theft. She fled to Dallas moments before police came to arrest her, but was apprehended and found guilty in 1977.

Elizabeth Carmichael went on the run for a second time

It should have been obvious to everyone that Elizabeth Carmichael never intended to go meekly to prison. As Bustle reports, after being indicted in 1975 she fled and was eventually found in Dallas and brought back to face trial in 1977. Her previous identity revealed, she was found guilty of a slew of old charges as well as charges connected to the fraud surrounding The Dale. She was sentenced to 10 to 20 years in prison and ordered to pay $30,000 in restitution.

As Jalopnik reports, Carmichael posted $50,000 bail—and lost no time in skipping town. As The New York Post notes, Carmichael had plenty of experience running from the law, as she'd spent years doing so with her family in the 1960s. This time, she vanished completely for 12 years.

In 1989, she was the subject of a an episode of Unsolved Mysteries on NBC (where it was implied that she was a cross-dresser in order to hide her true identity). Esquire reports that just minutes after the episode aired, a viewer called into the show's tip line and identified Elizabeth Carmichael as living under the name Katherine Elizabeth Johnson (interestingly, in the town of Dale, Texas, where she ran a flower shop).

She spent 18 months in prison

After being on the run for 12 years, Elizabeth Carmichael was apprehended in 1989 and finally brought to justice. It proved impossible to separate her gender identity from her crimes—though, as noted by The Guardian the court system surprisingly affirmed her gender identity. According to Biography, she formally petitioned the court to be addressed as a woman at her trial, which the court granted—meaning that she was legally recognized as a woman.

But as Time notes, that didn't stop the legal system from treating her as a man masquerading as a woman. Throughout her trial it was implied that she was merely a cross-dresser seeking to throw the law off her trail, and despite her own request to serve her sentence as a woman and the court's prior rulings, she was sentenced to serve 32 months in the Men's Central Jail in Los Angeles. While serving her time there, Carmichael was unsurprisingly attacked and beaten severely.

According to Esquire, Elizabeth Carmichael ultimately served 18 months of her term in the Men's Central Jail before being granted parole.

The media was incredibly transphobic

It might not be surprising that the media of the 1970s and 1980s wasn't particularly kind or sensitive towards a transgender woman accused of some pretty wild crimes—we're still struggling about these issues as a society today. But as Vanity Fair reports, the media were especially cruel to Elizabeth Carmichael because journalists didn't simply ignore her gender identity, they actively insinuated that it was part of her criminal scheme. Specifically, most of the coverage surrounding Carmichael speculated that she "posed" as a woman in order to evade the authorities.

As The Guardian reports, prior to the attention brought to Carmichael's story by HBO's new film about her, she had largely vanished from the public memory—in part due to her trans status. The idea that her identity was simply part of the con stemmed from a refusal to acknowledge a transgender woman's identity as legitimate, an attitude that could be observed at almost every point in her story. As historian Susan Stryker tells The Guardian, the trial became more about whether she was a "fraud" for living as woman.

Elizabeth Carmichael's legacy is fittingly complex

After being released from prison in 1993, Biography reports that Elizabeth Carmichael returned to Texas and appears to have lived a quiet life with no more attempts at grand money-making schemes or restless movements around the country. According to Esquire, she returned to the flower business and spent her later years with her family, and Hemmings reports she died after a battle with cancer in 2004 at the age of 77.

Or did she? Appropriately for someone who gave authorities the slip several times and lived under many assumed names, there's not a lot of certainty about Elizabeth Carmichael's fate. Time reports that the producers of HBO's film about Carmichael were unable to locate a death certificate (or a birth certificate, for that matter) for her. And Jalopnik reports that she was still alive in Austin, Texas, in 2013 (though they offer no source for this, and also incorrectly claim she spent 10 years in prison).

What's certain is that Elizabeth Carmichael is one of the most complex criminal figures in US history, and the lingering confusion about her final years is 100 percent on-brand.