What Life Was Like As A Member Of The Sultan's Harem In The Ottoman Empire

For much of history, the harem of the Ottoman Empire was purposefully mysterious. Sequestered in the Ottoman sultan's palace, the harem was a place that was physically set apart from not just the rest of the court but from the entirety of public life. The women inside were connected to the sultan, typically either by blood or by intimate relationship, and were expected to spend the vast majority of their lives apart from the world.

Because of this withdrawal, there was a dearth of information about what it was really like to live in the harem. Western observers, many of whom began reporting back about the harem and other aspects of Ottoman life in the 19th century, weren't especially careful or sensitive. Their accounts, influenced by their own assumptions and misconceptions, produced an inaccurate and sensationalist picture of the harem, as the journal Feminist Studies reports.

Now, however, more careful scholarship and accounts from Ottoman people and their descendants are producing a more complicated picture. Movement in and out of the harem was restricted and was also connected to practices that many will likely find troubling today, such as slavery. Yet, the harem was also a place where women could become incredibly powerful, especially if they were intelligent and paid careful attention to Ottoman politics. It was, in short, a complicated place to be. Here's what life was really like for the women in the imperial Ottoman harem.

Patriarchy, religion, and culture all played a role in the rise of the harem

The harem of the Ottoman sultan was no mere pleasure palace. Instead, it was a vital part of the imperial court and very necessary to the continuance of the throne. In fact, the entire concept of the harem was deeply linked to the cultural values and religious beliefs of the sultan and his massive household.

As Britannica reports, a private place set aside for the women of a household has been around since before Islam reached much of the Middle East. However, it is true that the rules of Islamic harems were more likely to require that the women inside keep themselves out of the public realm entirely. Islamic law also allows men to take multiple wives, so long as they can support them. This meant that the luxurious court of the Ottoman sultan could host a particularly large and complex harem.

The Ottoman Empire used both wives and concubines from within the harem to produce heirs, reports The Ottomans. It was all part of a hereditary system that passed power through patriarchal lines, so the more sons, the better — apart from all of the almost inevitable power struggles that resulted when too many sons vied for the throne. The use of non-married concubines was especially useful for the sultan, as wives had rights that some rulers found troublesome. A concubine, it was thought, wouldn't tie up the works by grabbing power for her own family.

Harem women lived an ultra-secluded life

The original point of the Imperial Ottoman harem was to keep the women inside entirely cut off from the outside world. That state was reflected in the very name of the place. As Boston College reports, "harem" has a variety of meanings, most of which typically translate as "forbidden," "sacred," or "inviolable." The privacy of the harem was, in part, a demonstration of the harem-keeper's status. The richer and more prestigious a man was, the more he was able to maintain a large and complex harem of women who, in theory, would have nothing to do with the outside world.

That concept was also reflected in the architecture of the Ottoman sultan's harem. According to Britannica, the harem of the Topkapi Palace, which was the sultan's main home beginning in the 16th century, was as physically isolated as it was socially cut-off. Anyone who was to enter or exit the harem had to do so through a gate guarded by eunuchs, who lived nearby. The valide sultan, or mother of the sultan, lived at the center of the harem in lavish apartments, from which she could direct the daily lives and intrigues of the people living there. The only person who didn't have to enter through the gate was, naturally enough, the sultan himself. Within the Topkapi Palace, he was able to enter the harem through a hammam, or bath, connected to his mother's living quarters.

The harem was a beautiful place but few could leave

Though the movement of women within and outside of the imperial Ottoman harem was very restricted, their space was at least well-appointed. According to the Topkapi Palace Museum, the harem in the sultan's abode boasted over 300 rooms, nine different baths, and even two separate mosques for worship. Many of these areas were richly decorated with colorful tilework, shining metals, and other fine details.

Now, tourists are able to enter the previously forbidden area as part of a museum tour. Once inside the harem, they gaze upon the richness of the space, though they may not instantly recognize some of the darker moments in the harem's history. Boston College reports that the "Twin Kiosks" of the harem, a small structure decorated with stained glass and once appointed with rich textiles and even a series of fountains, was actually a prison.

During a particularly tense period in Ottoman history, the sultan's male heirs were locked into the Twin Kiosks, set to live out a luxurious but highly restricted life until they either died or ascended to the throne. It was at least better than the previous practice of fratricide, wherein competitive brothers killed one another in a Game of Thrones-style quest to become the sultan.

Some harem women were enslaved, but some weren't

The status of the women within the imperial Ottoman harem varied greatly. Some were official wives of the sultan. Others, including a number of the concubines and servants within the harem, were enslaved. As The Imperial Harem reports, slaves within the Ottoman empire, including the harem, could not be Muslim. This meant that enslaved concubines were often taken in war and trained in different skills or arts by slave traders. Some of those woman who found their way into the sultan's harem traced their paths through these slave traders and markets, presumably within private spaces as opposed to public markets, as the University of Cambridge points out.

Slavery, which existed before Islam came to many countries throughout the region, was an everyday facet of life in the Ottoman Empire. The BBC reports that the Quran banned the enslavement of Muslims by other Muslims, allowed for slaves to achieve their own freedom, and banned the mistreatment of slaves. Quite a few slaves, including those within the harem, had the opportunity to convert and eventually leave servitude behind. However, it was always possible that real life did not necessarily live up to this ideal.

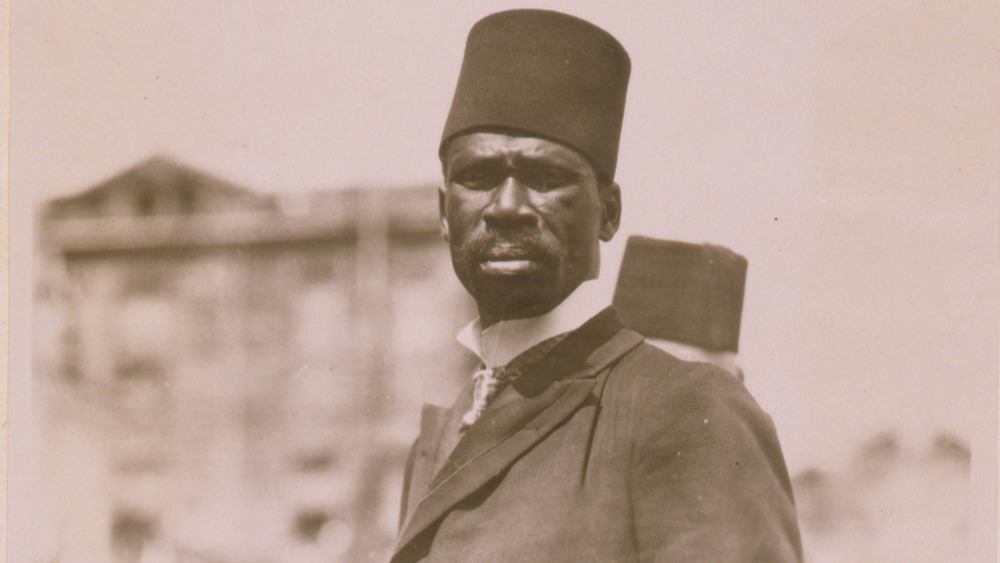

Eunuchs were the literal gatekeepers of the harem

Controlling the entrance of the harem and protecting the women inside were the near-legendary eunuchs. As the Institute for Advanced Study reports, eunuchs were another feature of pre-Islamic societies that seems to have reached their zenith in the Ottoman Empire. Like some of the women inside the harem, they were typically slaves. Eunuchs were generally men who had been transported from East Africa as boys. According to The Ottomans, some "white eunuchs" were also taken from Christian areas like modern-day Armenia and Hungary but typically didn't guard the harem.

At some point between their capture and their lives in the Ottoman court, they were castrated. This, at least in the minds of the sultan and his court, made them ideal guards for the harem. Eunuchs could be imposing and powerful, yet they lacked the necessary equipment to do anything untoward with the women of the harem. Neither did they have family ties to distract them, given that they had been snatched away from their homes at young ages and couldn't start their own biological families.

Despite or perhaps because of their ties to one of the most restricted areas of the sultan's palace, eunuchs stood to gain a lot of very real power. In an interview with the Middle East Studies Pedagogy Initiative, author Jane Hathaway explains that the chief eunuch could take advantage of vaguely defined roles within the court, especially before court roles became more defined in the 18th century.

The Sultan's mother ruled over the harem

Though it was secluded from the outside world, the harem still needed to function as its own entity. For much of its history as an Ottoman institution, this meant structure and hierarchy. And, as a hierarchy so often entails, someone had to be at the top. For a significant portion of the imperial harem's history, that person was the sultan's own mother.

The "valide sultan," as she was known, was so powerful that she occasionally stepped in as regent, according to The Imperial Harem. If she wasn't stepping in as a ruler, the valide sultan was still a pretty big deal. Per The Ottoman Lady, she wielded plenty of soft power when influencing her son, who would have spent a significant portion of his childhood growing up at her side in the imperial harem. Even after he moved to the royal throne, the sultan's private apartments were still located very close to his mother's.

Even if you weren't the sultan, but a woman in his harem, the valide sultan had a lot to do with the direction of your life. Hurriyet Daily News reports that the valide was typically in charge of which harem women got access to the sultan. The more a concubine caught the attention of the ruler, the more likely she was to get perks like private rooms, servants, and her own chance at power, making the go-ahead from the valide vitally important.

The Imperial Ottoman harem was very hierarchical

The valide sultan ruled at the top of what was eventually a highly structured harem full of different titles, rankings, and seemingly endless movement within the hierarchy. It gets all the more confusing because, as All About Turkey reports, the "sultan" title wasn't always reserved solely for the man ruling the Ottoman Empire. Beginning in the 16th century, both men and women who were part of the family could potentially be called a "sultan." Things got more complicated as the years progressed, so that, by the 17th century, a harem woman might be a "kadin sultan" or "haseki sultan," for instance.

So, what, exactly, was the power structure? According to The Ottomans, women could enter as "acemi," basically a kind of apprentice. When they got to the point where the sultan might pick them, they were "gediks." If they became pregnant and had a daughter, they got a nicer set of rooms and became a "kadin." All About Turkey also points out that "kadin" could refer to being a favorite wife of the sultan, while "ikbal" was reserved for favorite but still unmarried concubines. Meanwhile, at the very bottom of the pyramid were the "odalisques," female servants who were deemed unworthy of making it to the sultan's bedchamber.

Having a son meant someone was a "haseki." That brought even more privilege, though, if the sultan died, mothers of sons might have needed to watch their own necks in the ensuing power struggle.

Many harem women competed to be the sultan's favorite

Boston College reports that a haseki was the sultan's favorite and one of the few women who were in line to become the mother of a sultan, one of the ultimate power roles for Ottoman women. To get there, she had to catch the eye of the ruler, both through looks, talent, and charm. If she managed to do so and cemented her position by having children, she would benefit not only from the sultan's attention but from his royal accounts. A haseki sultan could get double or even triple the amount of money that was allotted to other harem women.

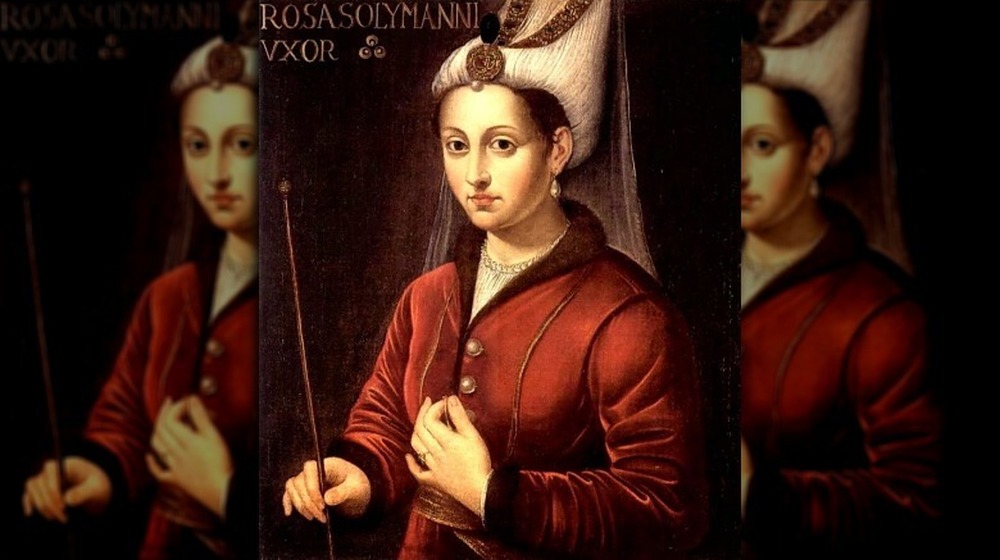

One woman became so powerful that she went from an unknown concubine to wife of sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. According to The New York Times, she hailed from Ruthenia, now Belarus and Ukraine. When she arrived in the harem at age 13, she began an intensive course of study and was named Hurrem, or "the laughing one." Suleiman was so taken with her that he neglected the other harem women, much to their consternation. Suleiman even continued his relationship with her after she gave birth to a son, which typically meant that a woman ceased to visit the sultan. She eventually achieved the extraordinary step of marrying the sultan and became valide sultan herself.

Being in the harem meant getting an education

Harem women were generally expected to be good companions outside of the bedroom, meaning that they had to have a certain level of education if they were ever going to make it in the Ottoman harem. In some harems, according to Al Jazeera, that included a basic level of education in things like literacy and household management. Things were different in the imperial harem, however. Per The Ottomans, entrants into the harem also learned the musical arts, were instructed in Islamic religious practices, had to be taught how to dance, and were often well-regarded for their storytelling prowess. The most successful or notorious women of the harem had to be as intelligent and capable as possible to make their marks on history.

They also had to learn the ins and outs of Ottoman politics, especially if they wanted to rise in power themselves. The Imperial Harem notes that women educated each other regarding the ins and outs of the political sphere, whether that was through outright instruction or by careful observation. The valide sultan also had to be well educated and politically savvy for the sake of her son, who often relied on her guidance as he ruled over the Ottoman Empire.

A succession of women once wielded extraordinary power from the harem

The rise of Hurrem, wife of Suleiman the Magnificent, in the 1530s may have at first seemed like an aberration. But, the succeeding generations proved that Hurrem had kicked off an extraordinary period of time in which the women of the Ottoman imperial harem held the most power they had ever achieved.

Called the "sultanate of women," this period of time spanned from about 1533, when Hurrem gained power, to the 1650s, according to Channel 4. The women in this period were preceded and followed by powerful women, too, though few reached their heights. Hurrem's rise to power, from an unknown harem woman to wife of the sultan, apparently unnerved enough people that those who followed her reigned largely as relatives of the sultan. Besides advising the sultan, they also commissioned architectural projects and took on charitable sponsorships to raise their esteem.

According to the Women's Islamic Initiative in Spirituality and Equality, Nurbanu was another woman who was stolen from her home for life in someone's harem. This time, she hailed from Italy and became the favorite of Selim, the heir apparent who would rule until 1574. As the mother of the next sultan, Murad, Nurbanu had to conceal her own husband's death until her son could return to the safety of the court, where she advised him for years and even communicated with other powerful women, such as France's Catherine de Medici.

Not all harem women were Muslim or Turkish

Though the Ottoman Empire was based in what is now modern day Turkey, and the sultan lived in Istanbul, now the capital of Turkey, this was no guarantee that the members of the harem or even the sultan himself were of entirely Turkish descent. As ThoughtCo reports, women in the harem could come from a variety of places within and outside of the vast Ottoman Empire. Some of the women who went on to become wives and mothers of sultans came from pretty far-flung places. These could include women who were often stolen from lands like Greece, Russia, Venice, France, and beyond.

Neither were all of the women inside the harem Muslim, though that was the prevailing religion for Ottoman royals. For concubines who were enslaved, they specifically could not be Muslim, as the Quran doesn't allow for Muslims to enslave each other, according to the BBC. Eunuchs, who were also slaves alongside many of the harem women, were also often drawn from cultures outside the empire, such as Egypt and other parts of Eastern Africa.

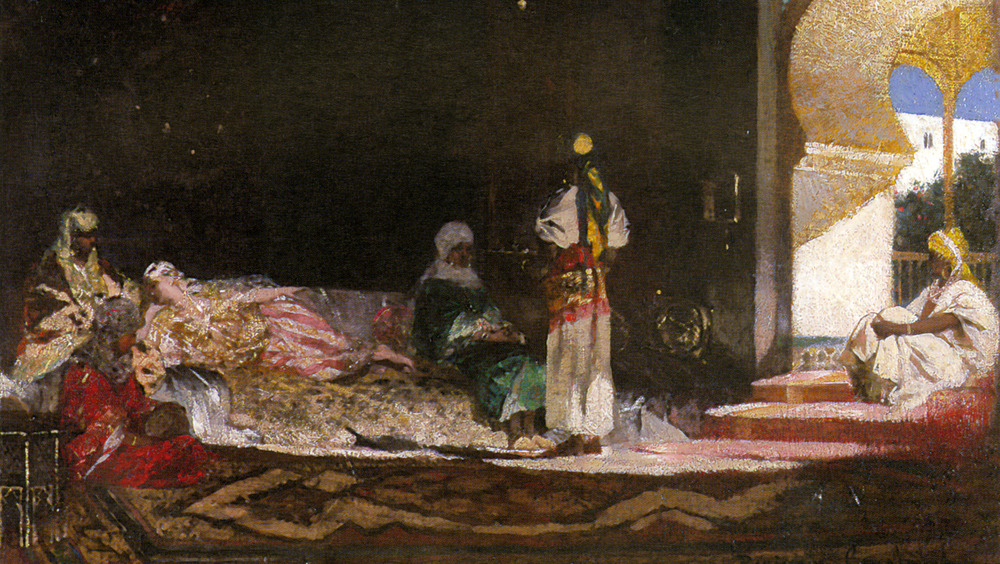

Westerners were fascinated by the harem but didn't always get it right

Much of what people outside of the Ottoman Empire knew about harems came from Western observers, who began producing accounts of their experiences in the 18th and 19th centuries. Yet, their tales of what they saw, including very limited glimpses of the harem, were colored by their own cultural perceptions and assumptions. The result, as Western Oregon University explains, was a flood of shocking and titillating fantasies that had little connection to reality.

As the journal Constellations reports, stereotypes established by men, like artists who produced rather scandalous paintings of scantily clad harem women, persisted through the centuries. Never mind that Western men were given practically no access to the harem, or that later accounts by women presented a more complicated picture. Even then, Constellations maintains that Western female observers were still influenced by their own preconceptions of the Ottoman Empire and Islamic culture.

The echoes of this orientalism and ethnocentrism are still felt even today, as Leila Ahmed argues in Feminist Studies. The idea of an exoticized, restrictive, and oversexualized harem is now often tied to assumptions that Islamic societies are "backwards" or "uncivilized." However, like arguably all human societies, cultures with majority Muslim populations are so diverse and complex that distilling them down to one-note stereotypes is often deeply harmful. Stories about life in the Ottoman imperial harem are inextricably linked to this tension, caught between Western fantasies and the concealed reality.