The Tragic Real-Life Story Of Squanto

To schoolchildren, the name Squanto is associated with Thanksgiving feasts involving kids using tin safety scissors to cut up construction paper to make either faux Pilgrim hats or Native American headdresses. Squanto was the so-called "friendly Indian." He helped the English Pilgrims survive the first brutal years of the Plymouth colony through his skills as a translator and a teacher.

While this grade-school assessment on the surface is correct, the truth is far more complicated. Squanto was a highly complex man whose character was shaped by tragedy. Squanto knew enslavement, exile, and genocide before his own suspect demise. He was far more worldly and far more well-traveled than the English of Plymouth. He was an intelligent, ambitious man who had a cunning streak that would make Machiavelli proud and who ultimately wanted to be a grand sachem. Squanto was also more than a "friendly Indian." Let's take a look at the tragic real-life story of Squanto.

Squanto's name was rage

The man who became known to history as Squanto was born as Tisquantum. According to Smithsonian Magazine, the name meant "rage" and in particular the rage of one of the divine spirits his people worshipped. According to Biography, historians estimate that Squanto was born around the year 1580 in the area of what became Plymouth, Mass. Squanto was a member of the Patuxet tribe of Native Americans, which was one of a number of coastal tribes in Massachusetts and Rhode Island that were part of the Wampanoag Confederation. While each tribe thought of itself as a separate entity, they all spoke dialects of Massachusett, an Algonquian language. The Patuxet themselves called their land the "Dawnland" and the inhabitants the "People of First Light."

The Patuxet were situated along Cape Cod Bay with its shallow water, while ashore the people grew fields full of maize. Squanto's home was a wetu, a hut of arched poles that kept inhabitants warm and dry. It was in this environment that Squanto gradually was educated, learning to hunt, fish, and cultivate maize. He became most likely a pniese, which was a counsellor and retainer to the local sachem. Unfortunately, there is no record of what Squanto looked like, but considering his skills, he must have been physically formidable, indeed.

Kidnapped and enslaved

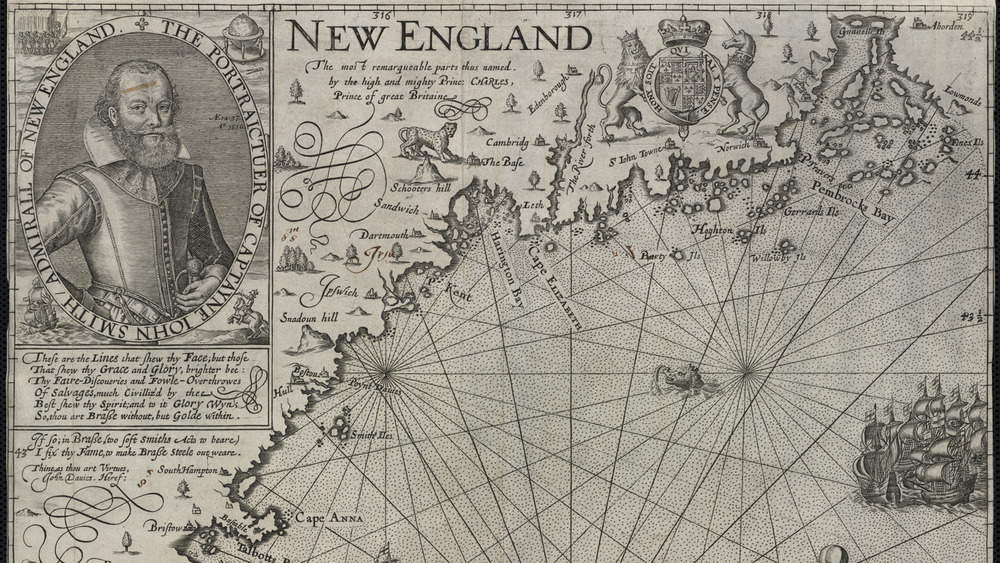

According to an article in the Massachusetts Archaeological Society Bulletin, by Jerome P. Dunn, Squanto's world turned immediately upside down when in 1614, he and 19 other Native Americans were captured by Thomas Hunt. Hunt was the captain of one of the ships of a trading and exploration mission led by the famous Capt. John Smith, who is known for his leadership at the tragic start of the Jamestown colony in Virginia. Hunt was looking to make the voyage more profitable and had only a cargo of dried fish. He put the Patuxets, as well as other Wampanoags he had captured, below decks and made for Malaga, Spain. There, he sold some of the Native Americans into slavery, but before he could sell Squanto, Catholic friars came and confiscated the prisoners.

The Catholic Church, as related by Smithsonian Magazine, rejected and condemned brutality toward Native Americans. They wanted to save Squanto's body from slavery and save his soul through conversion to Catholicism. It is unclear if Squanto did convert, since there is no record of him being a practicing Catholic. He very well might have in order to placate his saviors to extricate himself from a dire situation.

It is unclear what exactly happened next, but Squanto convinced the church authorities to release him with the intent for him to return home. It is in this way that Squanto made his way to England on a ship to Bristol.

Merry Old England

According to Jerome P. Dunn's research, Squanto made his way to London where he lived with John Slany at a place called Cornhill. Slany was a treasurer of the Newfoundland Company. The Smithsonian Magazine speculates that Squanto learned English from Slany, who kept him probably as a curiosity. Yet Squanto was more than a mere curiosity. A Native American skilled in English as well as Native American dialects would be invaluable for trading and exploration ventures.

The English had come into many conflicts with the Native Americans of New England. It was in this way that Squanto probably convinced Slany to send him back to North America. Squanto probably hoped that he could return to Patuxet. Slany agreed, but Squanto ended up in Newfoundland, which was too far from Patuxet with too many tribes that were unfriendly to the Wampanoags.

It was while Squanto was in Newfoundland that he met the explorer Capt. Thomas Dermer. Squanto sang the praises of his homeland to Dermer. This peaked Dermer's interest, and he took Squanto back to England. There they met with Sir Ferdinando Gorges, who had attempted to establish a colony in Maine but failed due to efforts by the Native Americans to drive the Europeans out. Gorges was interested in trying again and gave Dermer a commission. After touching down in Maine in 1619, Dermer sailed with Squanto and five or six other men south toward Patuxet. It was there that Squanto would receive the greatest shock of his life.

Squanto's sorrow

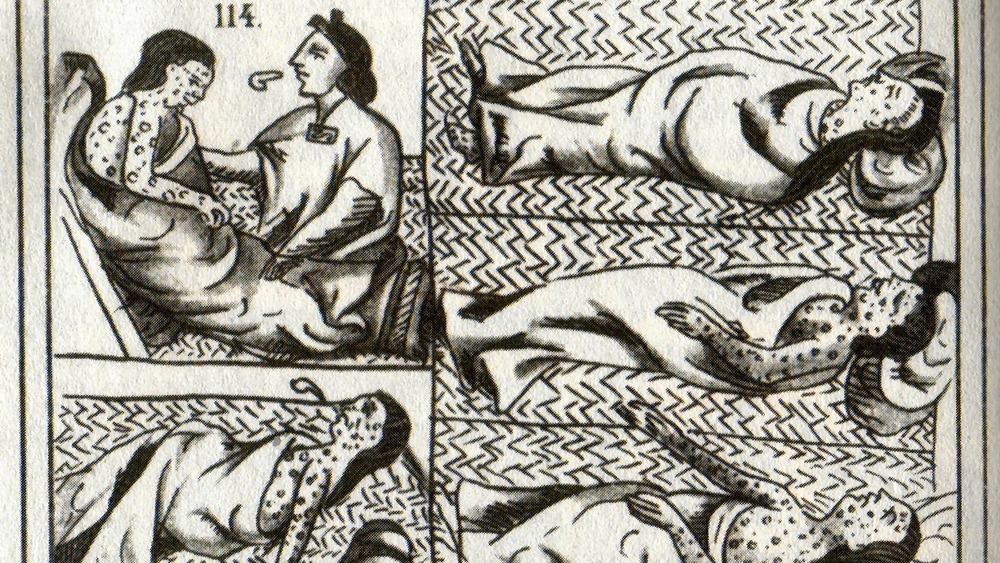

Squanto's people were the victim of the Columbian Exchange. According to Harvard University, the Columbian Exchange was the transfer of plants, ideas, food, people, animals, and diseases between the Americas and the Eastern Hemisphere. Unfortunately, Native Americans died in pandemics of Old World diseases to which they had no natural immunity. Scholars estimate that perhaps up to 95% of the Native American population may have been killed in the first 150 years after Christopher Columbus made landfall in the Americas in 1492.

John Booss, writing in the Historical Journal of Massachusetts, relates that while Squanto was gone, from 1616 to 1619, lethal plagues erupted among the Wampanoag people. He estimated that about 90% of the population succumbed to an unknown disease probably introduced by European traders, explorers, or fishermen.

Thomas Morton, a colonist, wrote of the matter in his Manners and Customs of the Indians in 1637. "The hand of God fell heavily upon them, with such a mortal stroke that they died on heaps as they lay in their houses; and the living, that were able to shift for themselves, would run away and let them die, and let their carcasses lie above the ground without burial. For in a place where many inhabited, there had been but one left to live to tell what became of the rest; the living being (as it seems) not able to bury the dead, they were left for crows, kites and vermin to prey upon...."

The Last of the Patuxets?

One article in the New England Quarterly reports that Squanto was considered the last of the Patuxets, although the Historical Journal of Massachusetts reports that about 90% of the Patuxet people had succumbed to the disease. Either way, it would have been devastating to Squanto, who spent many years on an odyssey to return home. In the meantime, according to Smithsonian Magazine, Squanto found his way to Massasoit, who was the head sachem of the Wampanoag Confederation. The sachem was soon pressed with a political dilemma when in 1620, a group of English settlers, known to history as the Pilgrims, had begun a new settlement at Plymouth.

This sudden depopulation made the settlement of Plymouth much easier for the English. This was unprecedented as, before, the only contact between Europeans and the Native Americans had been brief trade excursions with the Native Americans — making it plain that the Europeans were not welcomed on a permanent basis.

Massasoit faced a dual problem since the Wampanoag's rivals, the Narragansetts, had not been touched by the disease. Massasoit wavered between attacking the English or helping them. According to Nathaniel Philbrick in Mayflower, Squanto advised Massasoit that it would be catastrophic to attack the English, because they had muskets, cannons, and could unleash disease on them. This convinced Massasoit to seek an alliance with the English.

Squanto the treaty maker

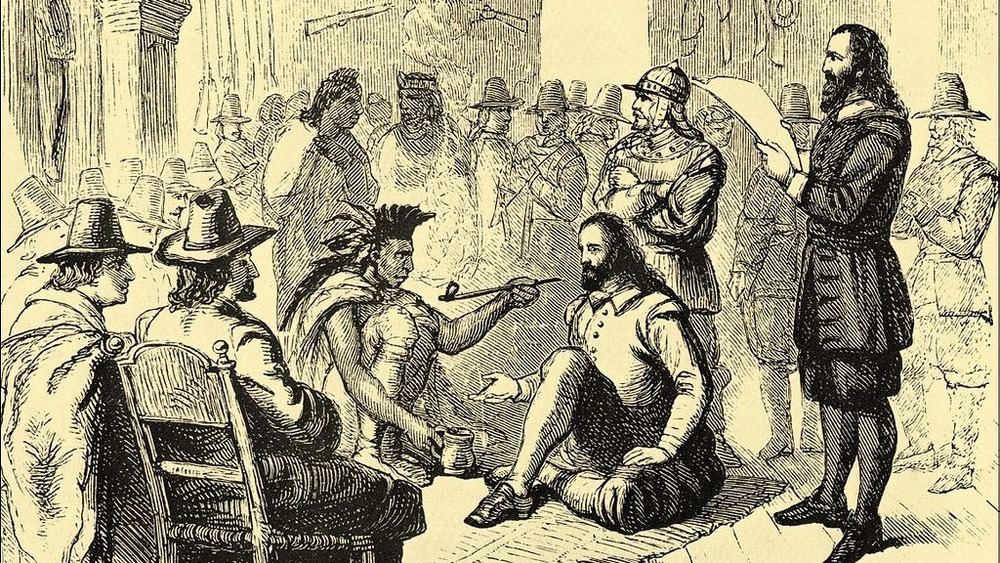

Nathaniel Philbrick's Mayflower relates that Massasoit was suspicious of Squanto, so in order to make first contact with the Pilgrims, the sachem sent Samoset, a visiting sachem, on March 17, 1621, says Smithsonian Magazine, to the fledgling settlement. Samoset carried with him two arrows, one with a head and the other without. These he presented to the Pilgrims to find out if they wanted war or peace. Samoset, however, only spoke rudimentary, broken English, so after these preliminaries, Massasoit and Squanto joined Samoset on a second visit on March 22.

Squanto, with his fluent English, acted as translator and enabled a treaty of friendship in which both Pilgrims and Wampanoags promised not to do violence to one another and aid one another if attacked. This was to the benefit of Massasoit, who could use the English as a deterrent against rival tribes in the region, such as the Narragansett. After the alliance was formalized, the New England Quarterly relates that Massasoit ordered Squanto to live among the Pilgrims and act as his go-between. This was meant to ensure to the Pilgrims of Massasoit's good faith and friendship.

Squanto the teacher

Squanto proved to be valuable to the survival of the Plymouth colony. The soils of New England, prior to the arrival of the Pilgrims, had been depleted of nutrients from native agriculture. According to the New England Quarterly, Squanto schooled the Pilgrims on Native American agricultural techniques. This included, as reported by the Cape Cod Times, using fish to fertilize the soil then planting maize, beans, and squash together. This method, however, was abandoned by the Pilgrims for more traditional European methods.

Perhaps of equal if not more importance was that Squanto helped the Pilgrims establish trade contacts. The Pilgrims used these contacts to obtain animal pelts, which they used to pay their financial backers in London. Squanto, as translator and liaison, became invaluable to the English. Without him, there would have been no first Thanksgiving in American history, which was more of a diplomatic negotiation than a kumbaya feast.

In fact, this raises the question of what Squanto's goals were as he became increasingly tied to the English colony. In the summer of 1621, Corbitant, a rival of Massasoit, threatened to kill Squanto, viewing him as the mouthpiece of the English. He was rescued by a detachment of English soldiers led by Miles Standish.

Squanto played his own game

William Bradford, the governor of Plymouth colony, later wrote that other Native Americans, "begane [sic] to see that Squanto sought his owne [sic] ends, and plaid [sic] his owne [sic] game, by putting the Indeans [sic] in fear, and drawing gifts from them to enrich him selfe [sic]; making them beleeve [sic] he could stur [sic] up warr [sic] against whom he would, and make peece [sic] for whom he would."

So what was Squanto's game?

Squanto's ultimate goal seems to have been to make himself a grand sachem and depose Massasoit. According to Smithsonian Magazine, Squanto realized that he could not stay in Plymouth forever and was already organizing a renewal of Patuxet with some of the survivors. To be successful, he needed to play the English and Native Americans against each other. Massasoit, still suspicious of Squanto and his intentions, sent a pniese, Hobamak, to monitor him in Plymouth. The pair quickly grew to be rivals.

Squanto wanted power

National Geographic reports that Squanto was using his power to try to peel away power from Massasoit. This is supported by the New England Quarterly, which explains that Squanto started driving trade away from Massasoit and to the Massachusetts tribes. Hobamak warned the Pilgrims that Massasoit believed that two rival tribes, the Massachusetts and Narragansetts, were in confederation against them — and that Squanto had been in secret communications with them.

Meanwhile, Squanto seemed to grow more emboldened. He also showed signs of trying to undermine the alliance between Massasoit and the Pilgrims. In January 1622, the Pilgrims received a bundle of arrows wrapped in snakeskin from a Narragansett chief, clearly not a friendly sign. Squanto advised the Pilgrims to send back a bundle of shot and powder in response. Diplomatically, the Pilgrims should have consulted with Massasoit before committing any action. It made Squanto seem to Massasoit more and more like a loose cannon.

Squanto makes his move

Squanto grew bolder. In early 1622 as detailed in the New England Quarterly, Squanto's efforts to undermine Massasoit were paying off. Wampanoags who typically went to the sachem for protection were now turning to Squanto. This was in part motivated by fear. Squanto was warning his fellow Wampanoags that the English could release the plague at will, and only he could control them. Gov. William Bradford wrote, as quoted in the New England Quarterly, that Squanto's words "did much to terrify the Indians and made them depend more on him, and see more to him, than to Massasoit."

According to Smithsonian Magazine, Squanto had been warning the Pilgrims that Massasoit would betray them by allying with the Narragansett and then attack. This was a set up on the part of Squanto. In April, just after Squanto left with some Pilgrims as part of a trading expedition with the Massachusetts, a member of the surviving Patuxets came running into the settlement. The Patuxet warned the Pilgrims that Massasoit and the Narragansetts were about to attack the Plymouth colony. Bradford in response sent the wife of Hobamak to Massasoit's village. She found all was quiet.

Squanto's head and hands

It became clear to Massasoit that Squanto was trying to use the Pilgrims to eliminate him. He called for the Pilgrims to hand over Squanto so he could execute him. His envoys offered Gov. William Bradford Massasoit's knife so that he could cut off the translator's head and hands. As related in the New England Quarterly, Bradford demurred and told Massasoit that while he would chastise Squanto, he could not lose him because he was too valuable for his colony. This created a terrible tension between the colony and Massasoit, since it, in effect, went against their treaty of friendship. Squanto for his part could not leave the Plymouth colony without an escort.

In October 1622, Squanto and Massasoit seemingly made peace, although clearly Squanto's life was still in danger. The tension would suddenly end when Squanto, who left on a trade expedition with the English, suddenly fell ill. He bled from the nose in what was described as "Indian fever." He died after a few days. The suddenness of the death has led some, such as Nathaniel Philbrick in Mayflower, to suspect that Squanto, who had been widely exposed to European diseases before, to think that his death may have been an assassination.

Squanto's legacy

According the New England Quarterly, at the time of Squanto's death, the political situation between the Native Americans and the colonists had grown incredibly complicated. It took several months for relations to reestablish themselves. Peace remained between the Wampanoags and the English for the remainder of Massasoit's life. As for Squanto, he has passed on into popular memory as the stereotypical "noble savage" or as Smithsonian Magazine pronounces, the "friendly Indian."

This popular conception of Squanto is unfair. As his history has shown, he was not only a highly intelligent and skilled person, he was also highly ambitious. It was this ambition which nearly undermined the fragile alliances of the early Plymouth colony. Perhaps this ambition stemmed from his tragic experiences as a captive followed by the destruction of his people. In all cases, Squanto must be appreciated as a considerable individual more than anything else. In the end, however, his untimely death was a capstone tragedy for this icon of American history.