What Really Happened In The Long, Hot Summer Of 1967

When discussing the long, hot summer of 1967, many recall the property damage that occurred. But in almost all of the cases, the property damage resulted as a reaction to police assaulting or murdering a Black person. For this reason, many of the uprisings cannot be described as riots because whatever peace there was had already been violently disturbed by the police.

Although there have been changes in the past 50 years since that time, the slew of police killings and subsequent Black Lives Matter protests across the United States in 2020 were demonstrative of the fact that many of the issues people protested 50 years ago remain today. And in 2020, many of these protests against police brutality were met with police brutality.

Unfortunately, after the summer of 1967, even though a presidential commission determined that white supremacy in the U.S. was responsible for the conditions that led to the necessity of an uprising, it was ignored. Instead, the government put resources into war and policing rather than social reform and did little to reform systemic and institutional racism in America. Here's what really happened in the long, hot summer of 1967.

Leading up to the long hot summer

Although the summer of 1967 is known as the long, hot summer, its first mention came in 1964. In St. Augustine, Fla., Martin Luther King, Jr., announced the beginning of a "'long, hot, nonviolent summer' of protest." And when the Civil Rights Act passed in 1964, it did little to actually stem discrimination, segregation, and racism across the U.S.

As a result, the long, hot, nonviolent summer of protest found itself extended past summer, past winter, into the summer of 1967, which became a long, hot, summer of uprisings, not all of which were nonviolent. According to KQED, the summer of 1967 became known as the "long, hot summer" because of the almost 160 uprisings that occurred in various neighborhoods across America.

While many described these uprisings as riots, many of the uprisings erupted as a result of police brutality. Others began as protests against "the systematic denial of employment opportunities by white-owned businesses and city services by white-led municipal governments," according to Encyclopedia Britannica.

The Week reports that by September 1967, over 80 people had been killed, and thousands were injured across the country. There were also "millions of dollars in property damage, with entire neighborhoods burned to the ground."

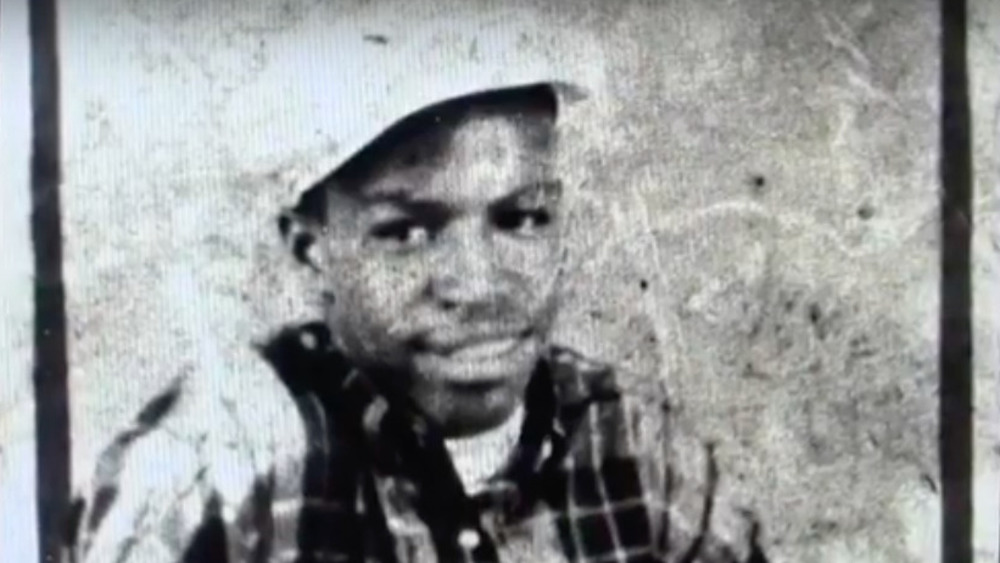

An unnecessary shooting in Tampa

On June 11, 1967, Martin Chambers, a Black teenager, was shot and killed by James Calvert, a white police officer in Tampa, Fla. Black Then writes that Calvert claimed Chambers wouldn't stop running away, but those who witnessed the shooting testified that "Calvert shot Chambers after he had stopped running and had his hands up against a chain link fence." His last words were, "Get me to a hospital, please, mister."

After hearing of the shooting, Black residents of Tampa started gathered around the scene. That night, some of the protesters began targeting businesses, and there was looting along Central Avenue as "arsonists meant to target just the white-owned" Central Avenue businesses. However, Tampa Bay Times reports that the flames ended up spreading to "at least three other buildings" on the street that was known as the "Harlem of the South."

Although 250 local law enforcement officers, 235 Florida High Patrol troopers, and 500 Florida National Guardsmen were called in to quell the uprising, what ended up actually helping were the residents who lived there. Known as the White Hats, Black youths, including those part of the uprising, were recruited "to walk the streets and encourage calm."

The uprising ended by June 14, but that day, according to the Equal Justice Initiative, State Attorney Paul Antinori announced that after two days of investigation, the shooting was deemed necessary. "The White Hats disagreed but continued working to keep the peace."

A death in police custody

Army Pt. Robert Hunt, 19 years old, was visiting friends and relatives in Cairo, Ill., on July 15, 1967, when he was stopped by police. Police claimed that he had a broken tail-light, though this was just one of many ways in which police harassed Black people for driving. Hunt ended up being arrested for disorderly conduct, and he was accused of being AWOL, even though he was on leave which, according to South of 64, Army records confirm.

In Faith in Black Power, Kerry Pimblott writes that police officers claimed that Hunt had hung himself with his own t-shirt soon after being taken into police custody. But when Preston Ewing, Jr., went to the jail after being informed of the death by the Black physician who examined Hunt's body, he found several inconsistencies with the police's story. Not only was the ceiling incapable of holding Hunt's weight, but his body also bore several bruises "suggestive of a struggle."

After hearing of Hunt's death, Black residents of Cairo poured into the streets in anger. Although city officials tried to claim that the uprising was "an act of unrestrained and indiscriminate violence, participants were highly selective in their choice of targets, focusing narrowly on the property of Cairo's small commercial and industrial elite."

White Hats appeared during this uprising as well, but this iteration was created by white residents who formed a violent vigilante group. "Cairo remained a city at war for the next few years."

Fanning the flames

In the summer of 1967, Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin, then known as H. Rap Brown, a Black power activist, was invited by Gloria Richardson to give a speech in Cambridge, Md. And on July 24, 1967, Al-Amin went to Cambridge, and, climbing on top of a car, gave a rousing speech to the crowd. As an activist who advocated for fighting the violence of segregation with violence, Al-Amin told the crowd that "if this town don't come [a]round, town should be burned down."

NPR reports that there were shots soon after his speech, and after being hit by a buckshot, Al-Amin left. A few hours later, the Pine Street Elementary School, located in the Black neighborhood of the town, was set on fire. However, the local fire department was whites-only, and they refused to put out the fire, "citing fears of being attacked."

As a result, the fire spread, burning 20 buildings to the ground. And according to Delmarva Now, "although the leaders of the black community in Cambridge today are careful to point out there was no rioting or looting, only a fire, history has recorded the events of that fateful day as a riot, nonetheless."

Governor of Maryland Spiro Agnew ended up casting all the blame on Al-Amin, despite the fact that violence was directed at the school, because 13 years after Brown vs Board of Education abolished "separate but equal" schooling, the county still maintained segregated schools.

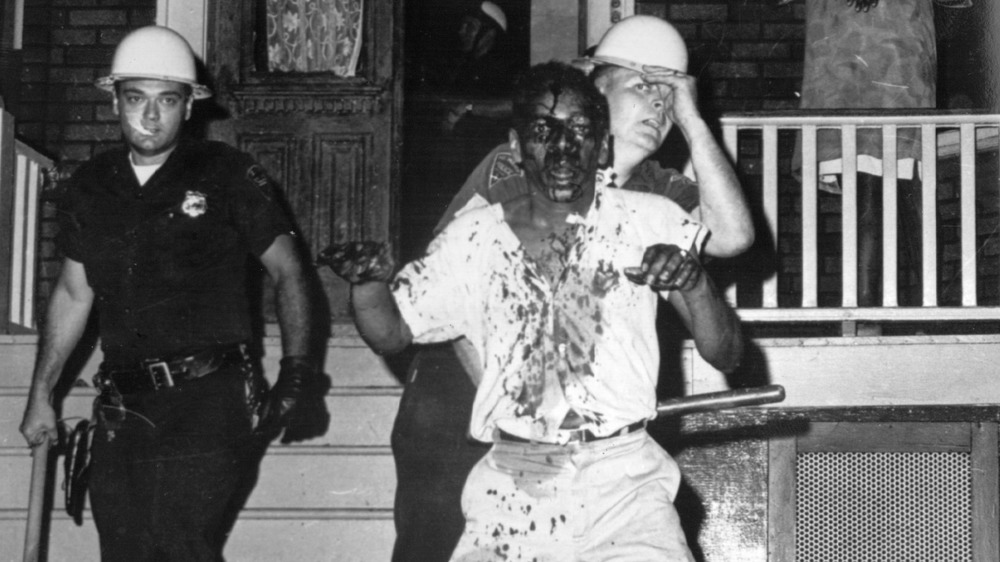

"beaten bloody"

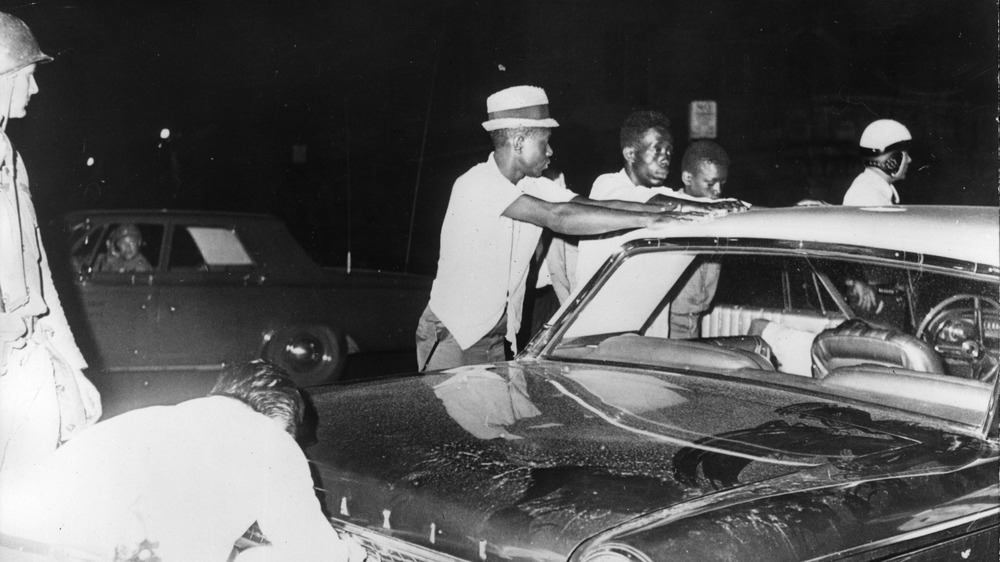

John Smith, a Black cab driver for the Safety Cab Company, was arrested on July 12, 1967, in Newark, N.J. The Atlantic reports that Smith "was beaten bloody by a pair of white cops" and taken to the Fourth Precinct, after being charged with minor traffic offenses.

According to the Library of Congress, a group of civil rights leaders demanded to visit Smith in jail. When saw the state of Smith and his injuries, they demanded that he be taken to a hospital. He left for the hospital using the back entrance of the precinct, but rumor had already spread Smith died while in custody.

A peaceful protest began outside the police precinct, but although the leaders of the protest called for nonviolence, the precinct was hit by two Molotov cocktails and "pandemonium began."

The uprising lasted until July 17, and by the end, 26 people, most of whom were Black, had been killed. At least 1,000 people were jailed, and over 700 had been injured. However, according to Timeline, most of the violence came from the state as they claimed there to be reports of Black snipers. As a result, "police and grand jury reports claimed that snipers were responsible for the deaths of unarmed Black civilians who were actually shot and killed by law enforcement."

A fight for fair housing

Although no one knows exactly what started the uprising, police brutality and housing discrimination against Black residents was widespread. According to Timeline, it's believed that after rumors circulated that police officers had beaten up several Black teenagers on July 30, 1967, "Milwaukee exploded."

According to The Encyclopedia of Milwaukee, fair housing issues were also at the heart of the uprising, since most Black residents lived in segregated housing, with the city split between north and south, "while the city council repeatedly voted 17-1 against a fair housing law [and] the school board made no concessions toward ending segregated schools."

Despite the fact that Police Chief Harold Breier blamed the uprising on "outside agitators," more than 90% of those arrested, over 1,700, were Milwaukee residents. Four people died, and at least 100 were injured.

The uprising lasted one day, but the campaign for open housing continued. One month later, the NAACP Youth Council and 200 protestors marched across the "city's 'Mason-Dixon line.'" They continued to do so for 200 consecutive days, and according to Black Power in American Memory, in 1968 President Lyndon B. Johnson passed a bill that "outlawed racial discrimination in 80% of the nations housing sales." Unfortunately, this did little to actually put an end to housing segregation. According to the The New York Times, "a city government report found that affluent, nonwhite Milwaukeeans were 2.7 times likelier to be denied home loans than white people with similar incomes."

The deadliest uprising

After William Walter Scott, II's unlicensed bar was raided by police in Detroit, Mich., on July 23, 1967, his son threw a bottle at the arresting officers. This bottle became the "catalyst for one of the most destructive civil disorders in U.S. history," according to Detroit Free Press.

Over the course of five days, thousands were injured, and 43 people were killed by the uprising. The Detroit Historical Society reports that over 7,000 people were also arrested. Arson and looting were reported during the first two days of the uprising, and by July 25 there had been almost 1,700 fires across the city. Tensions were also high after the murder of Danny Thomas, a Black war veteran, during the previous month. Although police had initially detained five men for the murder, only one person was charged for the murder, and he ended up being acquitted.

According to Timeline, myths of snipers were also spread in Detroit, despite the fact that "no organized groups of shooters were ever found." However, reports of organized snipers made it easier to justify "the arrival of battle-tested federal troops."

The uprising in Detroit has often been described as both a riot and rebellion. However, according to Joel Stone, a senior curator with the Detroit Historical Society, "the people who were on the street, burning, looting and sniping had some legitimate beef. It really was a pushback — or in some people's terms, a 'rebellion,' — against the occupying force that was the police."

"It's never been the same"

After a series of attacks and murders in the years leading up to the summer of 1967, Cincinnati police arrested Posteal Laskey, Jr., and convicted him of being the Cincinnati Strangler, although he was only charged for one murder. On June 11, 1967, police arrested his cousin Peter Frakes for blocking the sidewalk in Avondale during his protest of the conviction.

According to Cincinatti.com, another protest was organized for the following evening in response to how police had treated Frakes, since no white person had ever been arrested for "blocking the sidewalk." In addition to the treatment of Frakes, Black residents of Avondale were also protesting against housing and hiring discrimination.

The protest escalated as a rock was thrown into a church window, and a Molotov cocktail "was hurled into a drug store where earlier in the day a group of black youths had argued with a white owner," Timeline writes. But although white-owned businesses were targeted, the fires inevitably ended up spreading to Black businesses as well. It took two days to quell the uprising as 900 National Guardsmen were sent to Cincinnati, apparently with the order of "shoot to kill." By June 14, one person had lost their life, 63 were injured, and over 400 had been arrested.

After Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated the following year, Avondale was rocked by another uprising, and although these uprisings spread to other neighborhoods of Cincinnati, Avondale "suffered most" and "never rebounded."

An assault on white authority symbols

On July 19, 1967, while breaking up a fight between two Black teenage girls, Minneapolis police officers violently threw both girls to the ground. According to The Conversation, when a Black boy complained to the officer about how the girls had been treated, "another officer struck him too."

A protest was organized in response to the brutality, and after police arrived at the scene of the protest, "fights between residents and police broke out." The following day, the National Guard was called. Four days later the protest finally ended and over 30 people had been arrested, including children.

According to Mnopedia, some of the anger was also directed at Jewish business owners. Before World War II, Black and Jewish people were discriminated against equally, "so the Northside became an area where residents from different backgrounds cooperated, built friendships, and even intermarried." But as antisemitic discrimination decreased after World War II, this lead to strained relationships. Thus, many of the buildings that were targeted were Jewish-owned businesses and homes, although overall, the anger was focused on "white authority symbols, including businesses and property."

Unfortunately, the grand jury convened by the city decided that more police was needed in order to "better establish positive connections between police and communities of color." This was decided despite the fact that during the public forum that the city also convened it was made clear that the issue was the brutality of the police, not their lacking numbers.

Simultaneously as the "Summer of love"

Scholars have noted the juxtaposition of the long, hot summer with the Summer of Love, which represented for many white people freedom and liberation while their fellow Black citizens were simultaneously fighting for a fraction of that freedom. However, despite the fact that the people involved with both of these movements were fighting against the establishment, many who were part of the Summer of Love refused to confront systemic racism

The Summer of Love also coincided with the Vietnam Summer, during which thousands protested the Vietnam War. However, the white participants of the Summer of Love and the Vietnam Summer found themselves protesting for their futures while the Black participants of the long, hot summer were protesting for the present. Many of the "flower children" simply didn't want the suburban future of their parents, while many white protestors of the Vietnam War simply didn't want to die in Vietnam. Comparatively, Black Americans were protesting the fact that every day they were at risk of being murdered by the police.

According to The Week, many of the participants of the Summer of Love were "white and middle class," which also made their call for "a rejection of materialism sounded hopelessly naive." Especially since meanwhile, Black Americans were protesting for the ability to access these material goods "that the hippie culture was rejecting."

The Kerner Commission

In response to the long, hot summer of 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson established a presidential commission to examine its causes and to provide recommendations. Known as the Kerner Commission, they discovered that whiteness is created and maintained by white society. "What white Americans have never fully understood but what the Negro can never forget — is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it," states The Kerner Commission report.

And despite the fact that the uprisings were caused by varying and complex factors, the report noted that "certain fundamental matters are clear. Of these, the most fundamental is the racial attitude and behavior of white Americans toward black Americans. Race prejudice has shaped our history decisively; it now threatens to affect our future."

Unfortunately, as Smithsonian Magazine writes, nobody listened. If anything, the white backlash against the report likely helped Richard Nixon get elected that year. "Instead of considering the full weight of white prejudice, Americans endorsed rhetoric that called for arming police officers like soldiers and cracking down on crime in inner cities."

The legacy of the long, hot summer

Since no one listened to the Kerner Commission, it's no surprise that all of the issues that led to the various uprisings around the country remain the same over 50 years later. Almost every single incident of police brutality that sparked an uprising in 1967 finds its tragic parallel in the 21st century.

When Sandra Bland was stopped by police in 2015 for "allegedly failing to indicate a change of lanes," writes The Guardian, she didn't know that she was about to follow in Robert Hunt's footsteps. The arresting officer, Brian Encinia, claimed that he felt his life was in danger, which is why he arrested her, although he was later "charged with lying to investigators for saying his safety was in jeopardy." However, the charges were dropped after Encinia agreed to never again work in law enforcement.

Three days after her arrest, Bland was found dead in her cell, and her death was ruled a suicide, although "Bland's family have long remained suspicious of the circumstances."

Meanwhile, according to the Police Violence Report, in 2020, over 1,000 people were murdered by police. And although Black Americans make up 13% of the population, they are 2.5 times more likely to get killed by the police than a white American. Black Americans are also "more likely to be unarmed and less likely to be threatening someone when killed."