The Oldest Cold Case Solved With DNA

The story of a cold case might sound a bit like an unsolved mystery just waiting to be solved, but really, the fact that a case has gone cold at all is a major tragedy. A crime that's gone unpunished for years — decades, even — can't offer the slightest bit of closure to those affected. It's sad, to put it bluntly.

Luckily, new science and technology are on the rise to help. DNA analysis in particular has grown a lot over the past few decades, and one particular technique has started to become pretty popular in crime-solving circles, providing answers to dozens of cases in basically no time at all. And now, it's gone on to solve a 50-year-old cold case — the oldest one to be solved with DNA as of this writing.

Of course, that's fantastic news to hear. Closure and answers are rarely a bad thing. But at the same time, nothing is quite so simple as that. This new application of DNA analysis has brought up questions of legality and ethics that don't come with an easy answer by any means.

The murder of Susan Galvin

Despite what the case would eventually come to mean further down the line, it actually all started as a sadly simple kind of story, which took place back in July 1967. A young woman by the name of Susan Galvin was reported missing when she didn't arrive at her job as an overnight records clerk for the Seattle Police Department, on July 9, according to ABC News.

It didn't take long for her body to be found, and The Seattle Times says that her body had been left in the elevator of a parking garage at the Seattle Center. Only 20 years old, she'd been assaulted and then strangled to death, her body left behind to be found with no immediate suspects in sight. It was shocking and sudden, a murder that the Seattle Police Department felt hit close to home, as Galvin had been one of their own (via KIRO 7).

The case went cold

The crime scene was meticulously combed for clues. Investigators dusted for prints and examined Susan Galvin's clothes, but any trails provided by that route eventually turned cold (via ABC News). There just wasn't anything that was turning up.

But there was one lead that seemed to hold up. A professional clown who went by the name of "Punchy" seemed to be the most likely suspect (via KIRO 7). Galvin was known to like spending her free time at the Seattle Center, and she'd been seen with him in her last known location (the area that would later become the Seattle Center Armory). He'd recently quit his job and appeared to be a person of interest, but ultimately, the investigators couldn't really do much with their suspicions, according to The Seattle Times. There just wasn't enough concrete evidence pointing in his direction, and so they could never charge him with anything.

Every other possible lead that cropped up in the next 51 years went in much the same direction, always drying up and going cold. Common investigative techniques at the time just couldn't really solve it.

The history of DNA analysis

DNA analysis would end up proving to be something of a game changer when it came to criminal investigations, even though it didn't really start that way. The first official case solved using DNA analysis was a paternity test — no homicides or anything. A paper by Rana Saad describes a family trying to immigrate from Ghana to the United Kingdom. Papers were forged, and no one could verify whether a mother-son relationship was true, save by deducing their relationship through DNA

Eventually, though, DNA would start getting used to solve more high-profile cases. It was actually used to help identify the remains of Josef Mengele — the infamous Nazi scientist — and also solved its first homicide in 1986. An article by Chemical and Engineering News mentions Alec Jeffreys, who was consulted by police for the murder of Dawn Ashworth. Jeffreys had worked on the aforementioned paternity case, but this time, he collected DNA samples from 4,000 local men, only to find that none of them matched the samples found at the crime scene. The police had already gotten a confession — one that they suddenly knew was false, leading them to find the real culprit, Colin Pitchfork. DNA had both caught a killer and exonerated an innocent man.

DNA was also used in a similar way in Susan Galvin's case. Punchy the clown was cleared in 2016 since his DNA didn't match that found at the crime scene (via The Seattle Times).

The Golden State Killer

DNA analysis had been first used in criminal investigations in the 1980s, but that didn't mean it was widespread or universally useful. After all, early on, investigators needed a match between the unknown sample and a suspect (via C&EN). Without that, investigations couldn't really go anywhere, and comparing an unknown sample to literally everyone in a large area just isn't realistic. Things changed in 2018, though, with breakthroughs in the case of the Golden State Killer.

The Golden State Killer rampaged through California through the 1970s and 1980s, assaulting and murdering couples, absolutely terrifying Sacramento residents, who started sleeping with their shotguns near at hand (via NPR and ABC News). Despite the crimes being so high-profile, no one was actually caught, and the cases went cold for decades. At best, the Northern California killings were connected to other murders in Southern California via more powerful DNA technology in 2011, but things really picked back up in 2016 with the introduction of genetic genealogy.

The procedure completely revolutionized the search. Using just public DNA databases and a sample left behind at one of the crime scenes, Joseph James DeAngelo — a former police officer — became the lead suspect, eventually pleading guilty to 13 counts of murder in 2020. It became the first case solved with genetic genealogy, eventually inspiring many other investigators, including those looking into Susan Galvin's murder.

What is genetic genealogy?

Just because genetic genealogy makes use of DNA doesn't mean that it's exactly the same as old-school DNA analysis. Really, it's more of a combination between a couple different fields — genetic analysis and genealogical research (aka family trees).

On the genetic front, it depends on the way that DNA gets passed down. Each person has multiple pairs of chromosomes — carriers of genetic material — which means that, if you look at a particular pair, there are four chromosomes between two parents. Then when those two people have a child, those four chromosomes are cut up randomly into segments, and those segments are Frankenstein-ed into new chromosomes for the child (via Parabon). The same process keeps repeating with each generations, but what it means over time is that people who are more closely related will share not only more segments of DNA but longer ones. A paper by Ellen Greytak explains that the amount of similarity can then imply certain familial relations. A parent and child share a lot of DNA, while third cousins will share a lot less, if any at all.

Then comes the genealogy part. Public databases like Ancestry.com will basically take that shared DNA and spit out a list of relatives. From those names, it's possible to use public records (census data, hospital records, etc.) to build out an entire family tree.

How is genetic genealogy used in investigative work?

When it comes to criminal investigations, genetic genealogy has proven to be a really useful tool, Ellen Greytak lists 28 cases solved using this method by late January 2019 — within a year of its first use in the Golden State Killer case. By the summer of 2020, that number had already risen to 150 (via ABC News).

And there's a good reason for it becoming so widely used. The technique, all told, can potentially identify the owner of any unknown DNA sample, whether the sample comes from the victim or the perpetrator. If not narrowing it down to a single person, it can hugely slim the scope of an investigation, providing a small list of potential suspects (via Parabon).

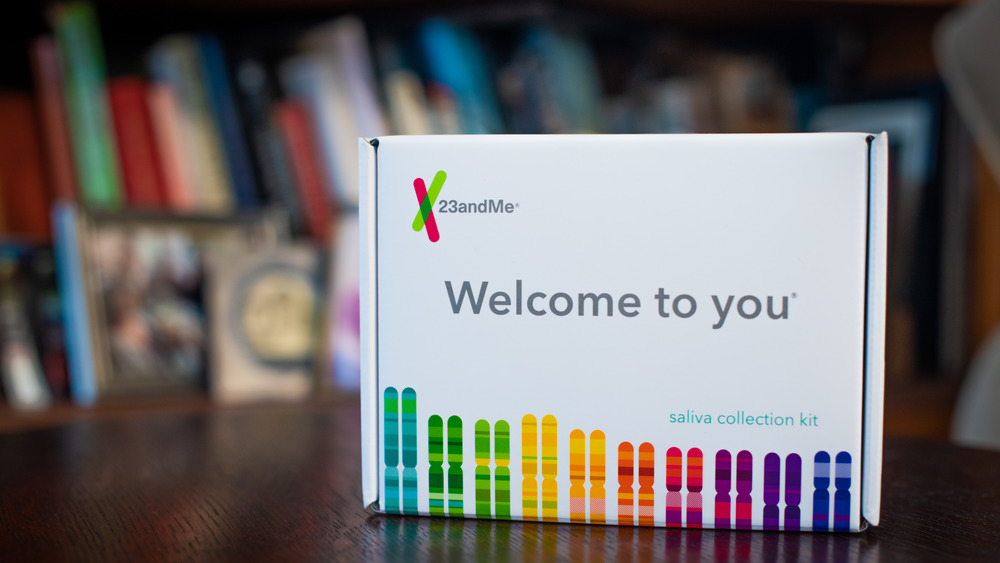

Forensic genealogist Deb Stone explained her process in an article from SeattlePI. She takes raw genetic data and uploads it to GEDmatch — another publicly available genetic database, similar to Ancestry.com and 23andMe. The database would present the closest genetic matches, and the level of similarity would give her some idea of the exact familial relation. From there, she would build back thousands of branches of those family trees, looking for a common ancestor. And then she would build down from that common ancestor, looking for a descendant that fit the given description.

It's pretty much exactly how Susan Galvin's murder ended up getting solved, too, with the family trees of a couple distant cousins triangulating on a suspect (via The Seattle Times).

So how did they find Susan Galvin's murderer?

DNA analysis had actually already been a part of Susan Galvin's case long before it was solved. The basic technique first became available around 2002, when her clothes — preserved for the past three decades — were taken to a crime lab for DNA analysis (via ABC News). The genetic material was sequenced but didn't turn up any hits in the FBI database of other convicted felons, making the case go cold again.

But that was until the Golden State Killer case brought with it genetic genealogy, and those techniques were put to use solving Galvin's murder. In 2018, the DNA samples of the presumed killer were sent to Parabon NanoLabs, and GEDmatch turned up two distant cousins — they each shared less than 2% of the DNA (via The Seattle Times). But both cousins were traced back to a couple born in the 1800s, and that couple's descendants were traced forward in time.

Using other clues — such as the indication of 16% Native American heritage and Polish surname patterns — a single man was found who fit the picture of the murderer — Frank Wypych. He'd been born in Seattle and would've been 26 at the time of Galvin's murder but was otherwise kind of unremarkable. He was a married ex-soldier with a criminal record and a couple kids, who'd died in 1987. But when his remains were exhumed for testing, well, the DNA matched, and the 50-year-old mystery was finally solved.

The investigators were determined to get closure for Susan Galvin's family

Of course it's cool to look into the technical stuff that went into solving Susan Galvin's murder — it's a mix of science and deductive logic and puzzles that seems worthy of a Sherlock Holmes story. But there's an emotional and sentimental side that deserves recognition.

Detective Rolf Norton took this case on, though his sentiments about the case were pretty reflective of those of the entire department — they'd always been hopeful that this would eventually come to an end (via AJC). Galvin had been one of their own, but at the same time, Norton said there was a certain innocence about her, despite working for the police (via SeattlePI). She'd go to the Seattle Center to "hangout and try to meet boys and have a Coke," so her death came as a shock.

And beyond that, Norton always thought of her family. He was solving it for them, which is finally what he was able to accomplish. Members of her family were there when the investigation came to an end. Her brother Chris Galvin was present at the announcement that the case was solved, with the police chief even presenting him with the flag flying over the Seattle Justice Center on the day Norton closed the case. Another brother — Lorimer "Larry" Galvin — also thanked Norton for finally giving them closure, though he mused that they would always have questions. Sure, they had the "who," but not the "why."

Genetic genealogy isn't perfect

Even though there's no denying just how helpful genetic genealogy has been in solving cases, that doesn't also mean that it's a perfect technique by any means. When it comes to the technological end of DNA analysis, there's been a lot of advancement over the decades, but there are still limitations.

Sensitivity has always been something that investigators need to consider. If there isn't enough of the DNA sample, then it's just going to be hard to actually do any kind of analysis (via SeattlePI). Fortunately, technology has provided a fix for that. Methods like PCR multiply the DNA present in a sample, so investigators can still get results from small samples (via C&EN). Just a few skin cells left on a surface that someone touched can be enough to sequence DNA.

But that sensitivity has drawbacks, too. A mixture of DNA from two different people can end up giving a jumbled mess of signals. Even a small amount of someone else's DNA will mess with results, calling into question what parts of those results actually matter. The problem can be solved with an arbitrary cut-off point, but is that the best solution?

Given all of that, it's a lucky thing that the original detectives in the Susan Galvin case processed it the way they did. According to The Seattle Times, they preserved the samples as if it was 2015 instead of 1967, when they had no idea the role DNA would later play.

Genetic genealogy cases have waded into a murky legal area

In general, Susan Galvin's case didn't really stir up too many legal troubles, but the history of genetic genealogy cases hasn't been quite so smooth.

The Los Angeles Times explained that the investigators on the Golden State Killer case weren't entirely transparent in how they solved it. Yes, they did make use of public genetic databases, but those didn't actually break the case. Instead, the vital information came from a civilian geneticist who uploaded the data to MyHeritage, breaking their terms of service by using their database for a criminal investigation. But both MyHeritage and FamilyTreeDNA (another similar genetic database) initially denied their involvement in the case. The lack of transparency and deliberate obfuscation of truth just didn't look good

But it didn't end there, The Atlantic bringing up other questionable cases. GEDmatch's terms of service allow for its usage in cases of murder or sexual assault, but detectives have tried to get around that, with civilian geneticists uploading samples without explicitly marking them for a case. Sometimes, it's even happened with the consent of one of the cofounders, who allowed a detective to use their services for a case of violent assault, because he saw it as "attempted murder" and figured he could let it go one time. Unsurprisingly, the news didn't go over well.

Really, the field is just so new that legislation and rules haven't quite figured out how to catch up, and the growing pains have caused problems.

Genetic genealogy raises questions about privacy

In general, the entire practice of using genetic genealogy as a technique in criminal investigations has led to a surge in questions about the state of privacy. Granted, to some level, privacy concerns have been considered. GEDmatch doesn't allow for anyone to view raw genetic data, because that would contain a lot more information than heritage (via Ellen Greytak). Health information, for example, deserves to stay hidden regardless of anything else.

But the inclusion of police investigations have added another layer onto things. The Los Angeles Times puts it simply — experts are worried that this practice can ultimately erode any kind of privacy standards and also broaden the power of the police. Strictly where terms of service and legality are concerned, the police have already proven that they're able to bend the rules in order to further their investigations (via The Atlantic). The promised privacy protections from these databases were proving flimsy when put under any kind of strain, which is concerning, to say the least.

Past that, though, there's an ideological argument to be heard. Plenty of people like to upload their genetic information for fun, looking to extend their family trees and learn something new. But now, all of a sudden, posting individual genetic information actually equates to posting about distant relatives at the same time. And maybe even incriminating them in the process (via The Seattle Times). The opinions on this are still divided, and there isn't exactly an easy answer.