The Crazy Real-Life Story Of Casanova

The name "Casanova" is one that has become almost universally associated with the idea of a seductive, promiscuous, and often untrustworthy lover. The man who inspired that term, Giacomo Casanova, was certainly all that and more. From 1725 to his death in 1798, Casanova served as an author, scholar, actor, violinist, spy, occultist, silk factory owner, soldier, gambler, wizard, layabout, libertine, and more. He met and made friends with such luminaries as Catherine the Great, Mozart, Benjamin Franklin, Voltaire, Goethe, and multiple popes. He was also a rapist, con artist, swindler, fugitive, and over-the-top, revenge-driven prankster. He contained multitudes, is what we're getting at.

While it would take multiple volumes to contain all the craziness of Casanova's whole life (literally: it's called Histoire de ma vie, and it's very long), here is just a sampling of the bizarre and unbelievable life of one of history's most famous — and infamous — lotharios.

A witch cured Casanova's nosebleeds

Giacomo Casanova was born in 1725 in Venice, the child of two actors, Gaetano Casanova and Zanetta Farussi. According to All That's Interesting, however, Casanova would grow to be skeptical that Gaetano was his real father, believing instead that he might have been the illegitimate son of Michele Grimani, the owner of the theater where his parents worked. Being the son of an illicit pairing between a courtesan and a nobleman was more in fitting with Casanova's own self-image as a high society man of low moral standards. Whatever the case, Gaetano died when Giacomo was young, and his mother left him to be a touring actress throughout Europe. As a result, young Casanova was primarily raised by his grandmother, Marzia.

As a child, Casanova was sickly and slow, suffering from frequent nosebleeds. When he was eight years old, his grandmother decided to employ the traditional remedy for stopping nosebleeds: witchcraft. Casanova, in his memoir, recalls being taken to the island of Murano, where they found an old woman sitting on a pallet and surrounded by black cats. The witch told Casanova that he'd be visited by a beautiful stranger: That night, he had a vision of a woman coming down his chimney and kissing him. Afterward, his nosebleeds stopped, he was suddenly able to read, and he had developed a taste for strange women.

Casanova got started with girls early

More than anything else, Casanova is associated with his reputation for being a prolific lover, so it's probably no surprise that he got started at an early age. Casanova says in his memoirs that on his ninth birthday, he was sent away from his home in Venice to Padua, where he lived in a run-down boarding house. He believed that his family was getting rid of him, but it may be that Padua's drier air was thought to be better for his health. While in Padua, Casanova's tutor was a young priest named Doctor Gozzi, who instructed him in both academic subjects and the violin. The young Casanova also received a different kind of education, however, at the hands of Doctor Gozzi's younger sister, Bettina. When Casanova was 11 and Bettina 14, the young man developed feelings for her that he didn't understand, saying she "kindled in [his] heart the first spark of a passion which, afterwards became in me the ruling one."

Bettina's kisses and what Casanova thought of at the time as innocent "caresses" ended up being the boy's first sexual experiences, though obviously not his last. As a teenager, he would lose his virginity to, and take the virginity of, sisters Nanette and Marton Savorgnan at the same time.

Casanova was a prodigy in more than love

Physical love was not the only subject in which Casanova was something of a prodigy. Even from a young age, he was notable for his quick wit and voracious appetite for learning. As All That's Interesting notes, Casanova entered the University of Padua in 1737 at the remarkable age of 12 and graduated with a degree in law at the age of 17. Despite his early success in the subject, Casanova had no great love for the law. In his own words, he felt "an invincible repugnance" toward the practice of law, which his tutor and guardian Doctor Gozzi had hoped he would pursue. Gozzi had specifically hoped Casanova would become an ecclesiastical lawyer, believing he would make his fortune that way. Instead, Casanova fostered an interest in medicine, to which he felt a calling. He said that given his way, he would have been a physician, "a profession in which quackery is of still greater avail than in the legal business."

In the end, Casanova never served as a lawyer or a doctor. He also studied moral philosophy, math, and chemistry, but the main thing he learned at the university that would go on to be one of his greatest pursuits was gambling. Casanova's gambling debts became so outsized in his college years that his grandmother had to come and bring him back to Venice.

How Casanova gained and lost his first patron

Although by this point, it might be hard to think of the amorous and gambling-prone young Casanova as an instrument of the Christian church, the fact is that after returning to Venice, Casanova was given minor orders by the patriarch of Venice: That is to say, he was admitted as a low-level clergyman and began working as a clerical lawyer as his mentor had hoped. According to his memoirs, however, work as an abbe did not support the rock-and-roll lifestyle the young dandy was aiming for. As a result, Casanova worked to ingratiate himself to a wealthy senator in hopes that he would support him as a patron. This was, in fact, Casanova's strategy for much of his life.

In this case, the patron in question was Alvise Malipiero, a 76-year-old senator who owned a palatial estate and was "surrounded every evening by a well-chosen party of ladies who had all known how to make the best of their younger days." Casanova managed to make himself Malipiero's constant companion, and the elder man taught him about society, sumptuous food, and wine. This relationship was not to last, however. One day, the two men were visited by Therese Imer, Malipiero's 17-year-old neighbor on whom he had long had designs. When Malipiero left the room, Casanova and Imer started getting frisky, and Malipiero, catching them, drove Casanova out of his home with a stick.

Casanova's meeting with the pope went better than you might expect

It will probably not surprise many that Casanova's career within the church did not last very long. After the death of his grandmother, the most ardent advocate of Casanova's pursuit of a clerical career, the young man entered a seminary with the intent to become a priest, but his gambling debts soon landed him in prison (and not for the last time). His mother tried to get him a position working with a bishop, but Casanova quit when he decided the position wasn't for him. His memoirs relate that instead he ended up working as a scribe for the influential Cardinal Acquaviva, a position that led to the unlikely meeting of the lascivious young Venetian with Pope Benedict XIV.

Fortunately, it turns out that Benedict XIV had a sense of humor and appreciated Casanova's quick wit, which meant he wasn't insulted by Casanova's impertinent questions, such as asking for a dispensation to eat meat on Fridays because fish caused an inflammation of his eyes and for blanket permission to read any and all "forbidden books." The pope even said yes to the latter request but "forgot" to give him written permission. Casanova's church career would be ended when Cardinal Acquaviva dismissed him following his involvement in a scandal, but somewhat shockingly, a later pope would award Casanova the Order of the Golden Spur, a papal knighthood for those who had done great service to the church.

Yer a wizard, Giacomo

Following the end of his brief career with the church, Casanova found himself in search of new employment. He ended up buying himself a commission as a military officer, but the military failed to keep his interest and he abandoned his commission after he lost most of his money gambling. He briefly attempted to follow his heart and become a professional gambler, but he lost all of his money and fell back on the musical skills he learned as a child and played violin for a Venetian theater. In his memoirs, however, Casanova explains how his fortunes came to change in a major way.

One day, at the age of 21, Casanova left the orchestra early and chanced upon a senator who dropped a letter while getting into a gondola. When Casanova gave the nobleman his dropped letter, the senator asked him to come along. While in the boat, the senator — Don Matteo Bragadin — suffered a stroke. Casanova used his medical knowledge to save the senator's life, most importantly wiping away the mercury ointment another physician applied. Bragadin became convinced that such a young man with such extensive knowledge must have supernatural powers. The senator and his friends were devotees of the occult, so Bragadin basically adopted Casanova, bestowing upon him the wealth the young man needed for his libertine lifestyle. Casanova was at last the nobleman he envisioned himself to be.

An escalating series of pranks leads to Casanova's exile

For the next several years, Casanova lived the life of a libertine nobleman, all funded by Matteo Bragadin, for whom Casanova theoretically worked as a legal assistant. This allowed the young man to, as he says, "lead a life of complete freedom, caring for nothing but what ministered to [his] tastes." Casanova's tastes, of course, tended heavily toward gambling and erotic escapades. Casanova's patron mostly turned a blind eye to his dissolute lifestyle but did offer him warning that he saw his own youthful follies in his protégé and that Casanova should beware the possible consequences. In these instances, Casanova would "turn [Bragadin's] terrible forebodings into jest, and continue [his] course of extravagance."

Bragadin would turn out to be right, of course. Casanova's memoirs relate that after a merchant (with whose object of affection Casanova had a dalliance) embarrassed Casanova by sawing a bridge plank in half so that Casanova fell in the mud, Casanova did the only reasonable thing: He escalated the prank war. He tried to convince the merchant that his bedroom was haunted using the arm of a corpse that he himself dug up from a fresh grave. The merchant was so frightened by the dead arm that he fell paralyzed and never recovered. Whoops. Grave desecration and almost killing a guy, combined with an accusation of sexual assault (for which he was later acquitted), forced Casanova to flee Venice.

A spy stole Casanova's books of magic

It was during his self-imposed exile from Venice that Casanova met the love of his life, the Frenchwoman disguised in men's clothing whom he called "Henriette." She, a fugitive herself, captivated Casanova with her wit, intelligence, charm, and beauty. She broke his heart, however, leaving him a goodbye letter saying (wrongly) that he would forget her. Depressed by this loss, Casanova returned to Venice, had a hot streak in gambling, and used this money to sleep his way around Europe, including engaging in a four-way with two nuns and a French ambassador.

While in France, Casanova joined the Freemasons, which were generally a group attractive to intellectual men of society but whose secretive nature was particularly alluring to Casanova. He had already gotten heavy into cabalism while with Don Bragadin, and he was also pretty into the Rosicrucians, another secret spiritualist society. Casanova managed to attain the highest rank of Master Mason. All this forbidden knowledge came with a price, though. As his memoirs recount, the state inquisition of Venice hired a spy named Count Manucci to confirm Casanova's forbidden knowledge of the occult and to steal his secret library of books of magic. Thinking that Manucci was a diamond dealer, Casanova showed off his magical knowledge by teaching Manucci how to summon elemental spirits. It turns out this is not the best thing to do with an agent of the Inquisition.

Casanova's great escape

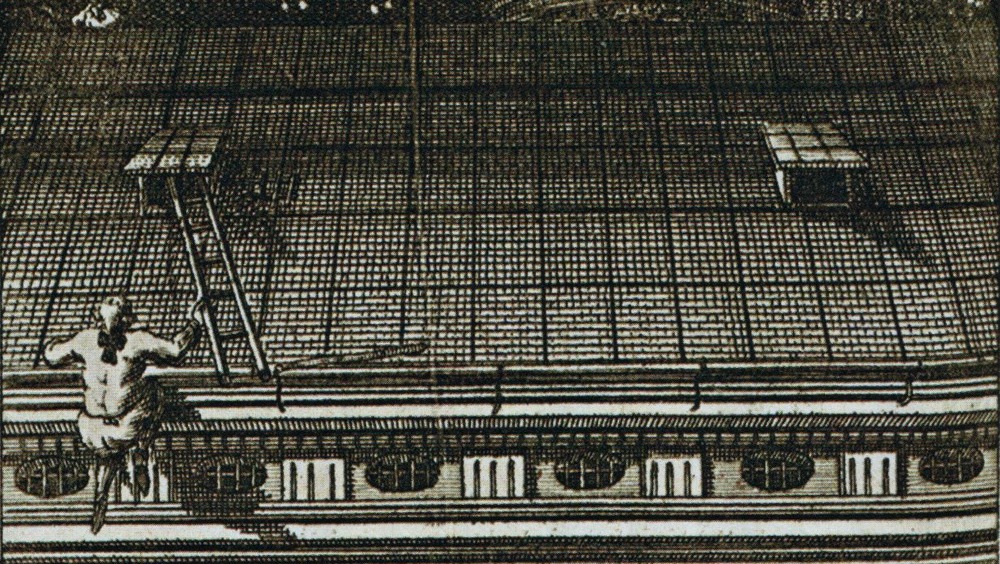

In 1755, the Venetian Inquisition seized Giacomo Casanova, and the young libertine's profligate lifestyle finally caught up with him. As All That's Interesting explains, Casanova was charged by the Inquisition with "blasphemy, cabalism, gambling, astrology, and Freemasonry," all considered heinous affronts to Catholic orthodoxy and public decency. Casanova was taken to the much-feared prison known as I Piombi, "the Leads," which were seven lead-roofed cells on the top floor of the palace of the Doge (the supreme authority of Venice, not the meme Shiba Inu). This torturously uncomfortable, flea-ridden cell was no place for a man of luxury such as Casanova, so he immediately began planning his escape. Casanova managed to acquire an iron bar, which he used to begin scraping a hole under his bed, which he knew would lead to the Inquisitors' chambers below. His plan was to break through on a holiday, when he knew the Inquisitors would be gone.

Unfortunately, three days before his planned escape, Casanova was moved to another room in the prison. Nevertheless, he kept trying, and with the help of a rogue priest, the two men managed to tunnel out through the roof of the prison on Halloween 1756. Casanova left a note: "Since you all did not ask my permission to throw me in jail, I am not asking for yours to get out."

Casanova's wizard rivalry with the Count de Saint Germain

After escaping prison, Casanova fled back to Paris, where he hooked up with old friends. One advised him that a smart way to get into the good graces of the Parisian officials would be to find a way to raise a lot of money for the state. To this end, Casanova helped establish France's first state lottery, and it won't surprise you that the silver-tongued devil was aces at selling tickets for it. This helped amass a great fortune for him, which he used to work his way into French high society. Once there, he used his reputation as an occultist, magician, and alchemist to con wealthy French people out of their fortunes. Notably, his excellent memory and facility for numbers helped him convince the upper crust that he had a wizard's numerological ability. Casanova became popular with such notable figures as Madame de Pompadour and Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

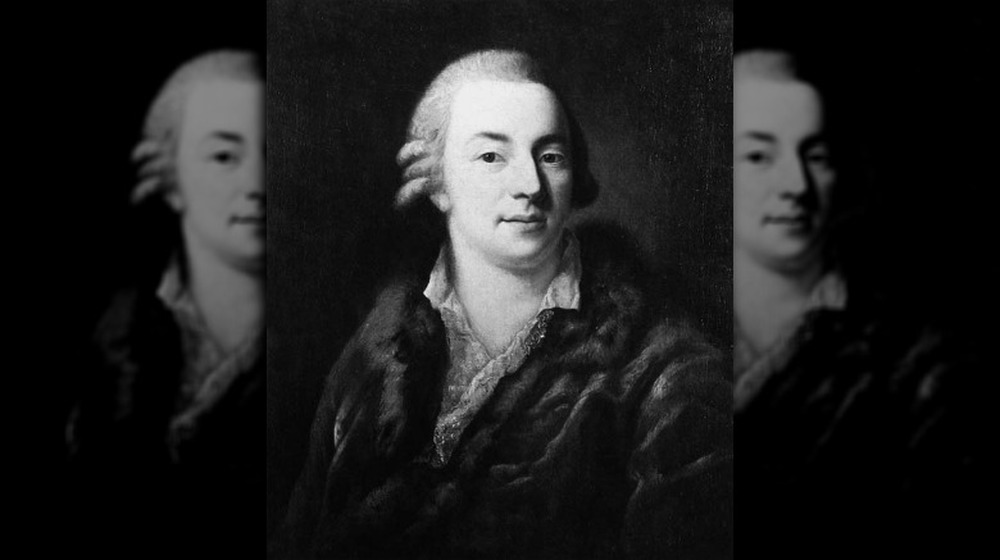

Naturally, he also developed some high-profile rivals in this way as well. Casanova relates in his memoirs that he found himself at loggerheads with another mystic in the form of the mysterious Count de Saint Germain (pictured above), a man whose reputation was (and still is) even more fantastical than Casanova's. Casanova describes Saint Germain as "the king of impostors and quacks," who convinced his marks that he was over 300 years old, that he could melt diamonds, and that he knew the secret of creating the Universal Medicine.

Casanova's long con

Make no mistake: despite the romanticism that has grown up around Casanova as a wit, a lover, and an adventurer thanks in large part to the popularity of his writings, in which he fosters his own legend, the dude was pretty scummy. As All That's Interesting records, of the 120 sexual partners he claims to have had in life, many were children, slaves, unwilling partners, and, in at least one case, his own daughter. He was also a con man and criminal who would do whatever he could to get the money he needed to afford his lavish tastes. While he claimed that "deceiving a fool is an exploit worthy of an intelligent man," people were still hurt by his deception and theft. One of the greatest victims of his con artistry and quack occultism was the Marquise d'Urfe.

As Do Travel Magazine explains, the then-63-year-old Marquise had an obsession with the occult and alchemy, as was fashionable at the time, and held salons to explore these topics. Casanova, with his great magical reputation, was, of course, an honored guest at these salons. He told the Marquise that she could give birth to a male child into which her own soul could be transferred so that she could regain youth and the greater magical potential of a male wizard. How would Casanova accomplish this? By having sex with her, of course.

Casanova had some notes for Mozart

When the sexagenarian Marquise d'Urfe failed to give birth to herself as Casanova promised, his fraud was uncovered, and Casanova eventually found himself banished from France by King Louis XV himself. There's too much in Casanova's insane life to fully relate here: He spent time as a spy, he owned a silk factory for a while, he failed to sell the idea of a national lottery to Catherine the Great, he almost lost his hand in a duel, he met Benjamin Franklin and talked about hot air balloons, he considered becoming a monk until a pretty girl walked by, and so on. In his final years, however, he found himself in Prague, where he worked as the librarian at the Castle Dux. It's also where he tried to tell Mozart how to do his job.

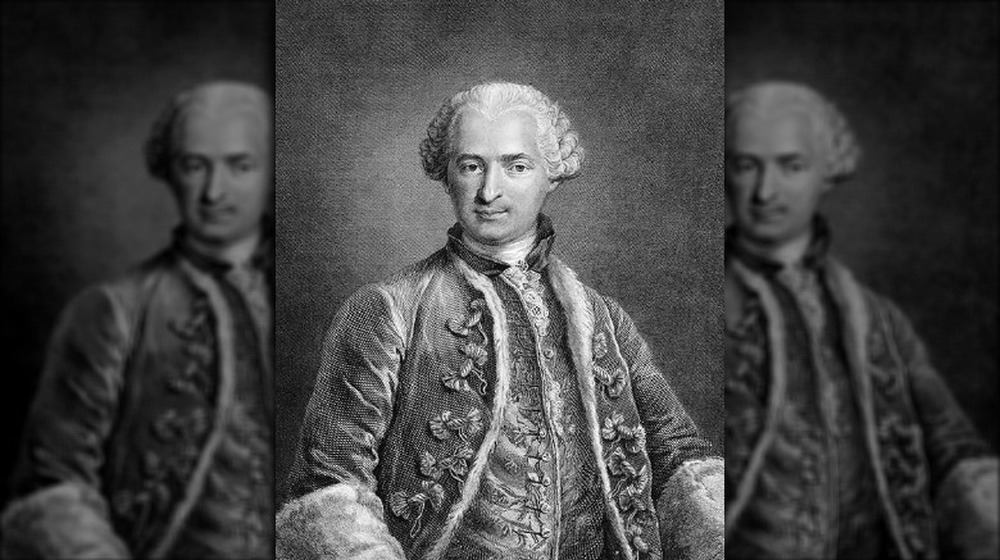

As Smithsonian Magazine explains, at this time, opera was a sensation in Prague, and Casanova had developed an interest in it himself. While in Prague, Casanova encountered one of his old friends from Venice, Lorenzo da Ponte, who was now working as Mozart's librettist. When Mozart came to Prague, it is believed that he and Casanova met. When Casanova found out that Mozart was working on Don Giovanni, about a compulsive sex man not unlike Casanova himself, he decided to send Mozart some notes, which may or may not have actually been incorporated into the work.